Vijay Prashad espouses confidence in rejecting the neoliberal capitalist framework, which arose against plenty of warnings over several decades and now exposes workers to the wolves of the “free market” during the pandemic.

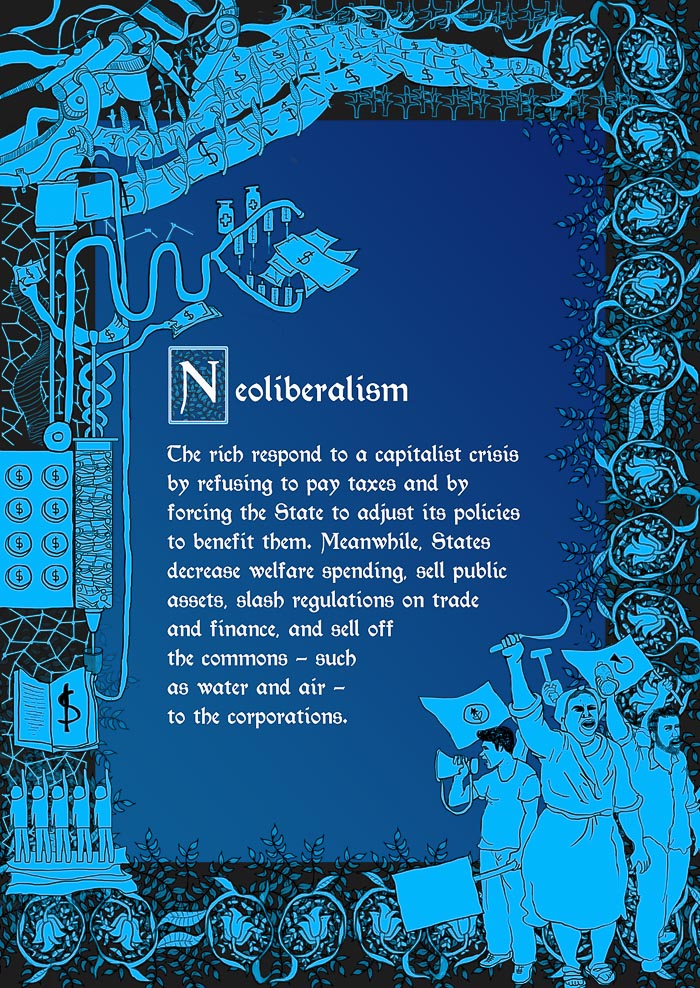

Greta Acosta Reyes (Cuba), “Neoliberalism,” 2020.

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

The novel coronavirus continues its march through the world, with 18 million confirmed cases and at least 685,000 deaths. Of these, the U.S., Brazil and India are the worst-hit, harboring about half of the world’s cases.

The novel coronavirus continues its march through the world, with 18 million confirmed cases and at least 685,000 deaths. Of these, the U.S., Brazil and India are the worst-hit, harboring about half of the world’s cases.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s claim that these numbers are high because of higher rates of testing is not borne out by the facts, which show that it is not testing that has ballooned the numbers, but the paralysis of the governments of Trump, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, and India’s Narendra Modi and their failure to control the contagion. In these three countries, testing has been hard to access, and the test results have been unreliably reported.

Trump, Bolsonaro and Modi share a broad political orientation — one that leans so heavily towards the far right that it cannot walk upright. But beneath their buffoonish statements about the virus, and their reluctance to take it seriously, lies a much deeper problem that is shared by a range of countries. This problem goes by the name of neoliberalism, a policy orientation that emerged in the 1970s to stabilize a deep crisis of stagnation and inflation (“stagflation”) in global capitalism. We define neoliberalism plainly in the image below:

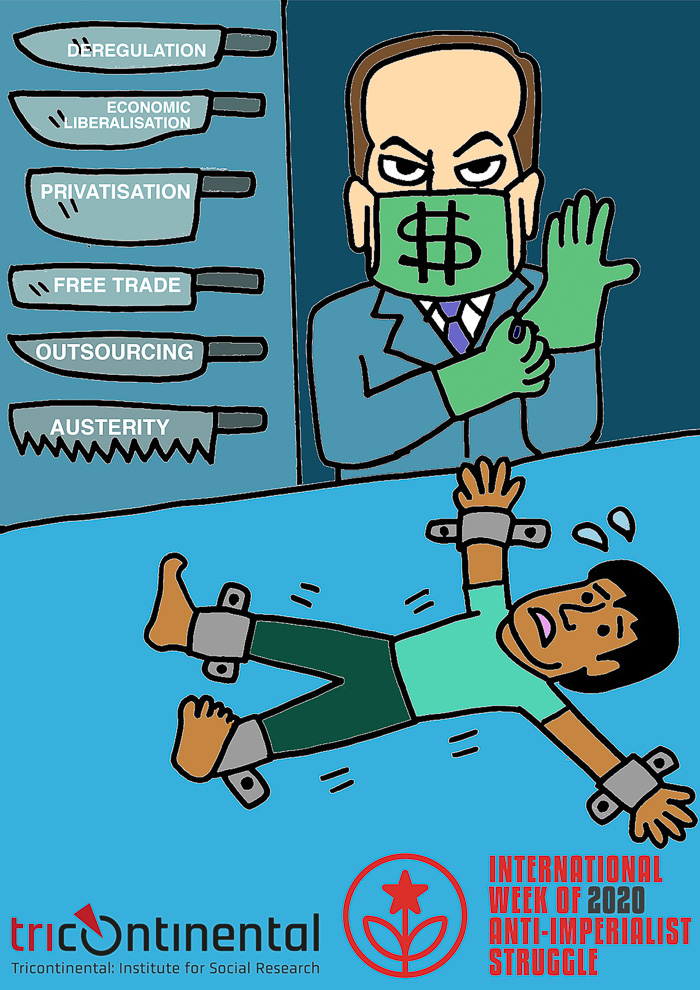

Vikas Thakur (India), “Neoliberalism,” 2020.

The tax strike by the very rich, the liberalization of finance, the deregulation of labor laws and the evisceration of welfare provisions deepened social inequality and reduced the role of the vast mass of the world’s population in politics. The demand that “technocrats” — especially bankers — run the world produced an anti-political sentiment amongst large sections of the world, who became increasingly alienated from their governments and from political activity.

Institutions of society that emerged to protect us from catastrophes of one kind or another were undermined. Public health systems were dismantled in countries such as the United States and India, while associated social services for childcare and eldercare were cut back or destroyed.

In 2018, a United Nations study found that only 29 percent of the global population has access to social protection systems (including income security, access to health care, unemployment insurance, disability benefits, old-age pensions, cash and in-kind transfers, and other tax-financed schemes).

A consequence of ending even meager social protection for workers (such as sick leave) and of failing to provide public universal healthcare is that in the case of a pandemic, workers can neither afford to remain at home nor can they access healthcare: they are left to the wolves of the “free market,” which is really a world designed around profit and not the well-being of people.

Choo Chon Kai (Malaysia), “Freedom of Choice,” 2020.

It is not as if there have not been warnings about the policy framework known as neoliberalism and the austerity project that it has driven. In September 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) warned about the deep cuts in public health spending — including the lack of hiring of public health workers — and the impact this would have if a pandemic were to break out. That was on the verge of this pandemic, although earlier epidemics (H1N1, Ebola, SARS, MERS) already showed the weakness of the public health systems to manage an outbreak.

From the onset of neoliberalism, political parties and social movements warned about the threats posed by these cuts; as social institutions are whittled away, society’s ability to withstand any crisis — be it economic or epidemiological — is damaged. But these warnings were dismissed, the callousness remarkable.

Kelana Destin (Indonesia), “Water,” 2020.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), founded in 1964, lit the red light of caution from the publication of its first “Trade and Development Report” (TDR) in 1981; this UN body tracked the new economic agenda premised on liberalized trade, debt-driven investment in the developing world and the slow emergence of a broad slate of austerity policies pushed by the IMF’s structural adjustment programs.

The austerity programs imposed on countries by the IMF and by the wealthy bondholders negatively impacted GDP growth and produced large fiscal imbalances. Growth in foreign direct investment (FDI) and exports did not necessarily mean an increase of incomes for people in the developing world. The TDR from 2002 explored the paradox that, while the developing countries were trading more, they were earning less; this meant that the trading system was rigged against these countries whose economies are largely reliant on exporting primary commodities.

The 2011 TDR looked closely at the after-effects of the 2007-08 credit crisis, which — it noted, “highlighted serious flaws in the pre-crisis belief in liberalisation and self-regulating markets. Liberalised financial markets have been encouraging excessive speculation (which amounts to gambling) and instability. And financial innovations have been serving their own industry rather than the greater social interest. Ignoring these flaws risk another, possibly even bigger, crisis.”

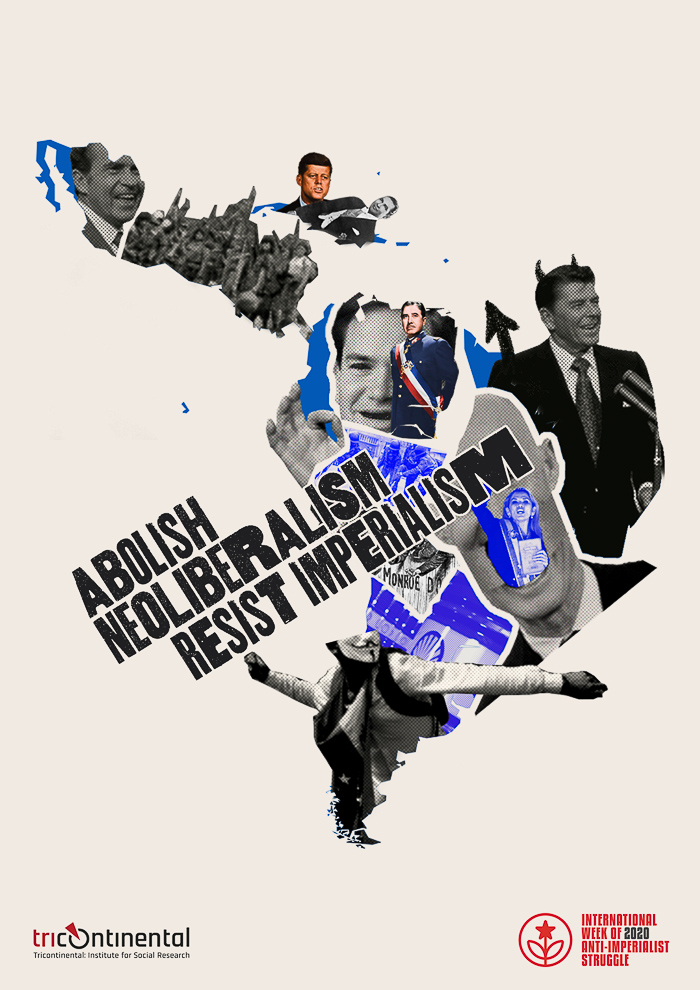

Lizzie Suarez (USA), “Abolish Neoliberalism Resist Imperialism,” 2020.

After re-reading the 2011 TDR, I wrote to Heiner Flassbeck, who was the chief of microeconomics and development at UNCTAD from 2003 to 2012, to ask him about that report and his feelings about it almost a decade later. Flassbeck re-read the report and wrote, “it seems to me that it is still a good guide into a new global order.”

Last year, Flassbeck wrote a three-part series of articles titled “The Great Paradox: Liberalism Destroys the Market Economy” in which he argues that neoliberalism destroyed the ability of economic activity to create jobs and wealth for the majority of the people. Now, Flassbeck wants to emphasize the importance of stagnant wages as an indicator of problems, as well as a place from which to develop solutions.

The 2011 TDR argued that “the forces unleashed by globalisation have produced significant shifts in income distribution resulting in a falling share of wage income and a rising share of profits.” The Seoul Development Consensus of 2010 had advised that “for prosperity to be sustained it must be shared.”

Apart from China, which developed a major scheme in 2013 to eradicate poverty and share growth, most countries saw wage growth fall short of productivity growth, which has meant that domestic demand grew more slowly than the supply of goods; nor were the possible solutions of relying on external demand or stimulating domestic demand with credit sustainable.

Pavel Pisklakov (Russia), “Invisible Hand,” 2020.

Flassbeck replied to Tricontinental: Institute of Social Research:

“The core of the matter is wages. That was missing in the TRD 2011. All attempts to stabilise our economies and bring them back to strong investment growth are futile if the wage question is not fixed. To fix it means to implement in all countries of the world strong regulation to make sure that wage earners are fully participating in the productivity growth of their national economies. In the developing world, this is understood in Eastern Asia but nowhere else. You need strong government intervention to force companies, national as well as international, to apply wage growth in line with productivity growth and the inflation target set by the government or the central bank. It can be pushed through by governments decisions about the increase of the minimum wage, as China did it, or by informal pressure on the companies, as Japan did it.”

In a recent report, Flassbeck argued that many developing countries — even in the midst of the coronavirus recession — look to the advanced capitalist countries, which are cutting wages, underspending, and pursuing failed policies of “labor market flexibility;” the IMF often forces along these policies, which are the “main hindrances to a better growth and development performance.”

This article is illustrated by posters from our ongoing Anti-imperialist Poster Exhibition. The first set was on the theme of capitalism; the second set is on neoliberalism, for which we received submissions from 59 artists from 27 countries and 20 organizations.

Vijay Prashad, an Indian historian, journalist and commentator, is the executive director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research and the chief editor of Left Word Books.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’

on its 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

This article gives a glimpse into the workings and exploitations of nominalism policies.But,how can world population resist these policies which are not of their own making but forced on them by the rich or developed Countries and the IMF? Countries where forced into structural adjustment/liberalization programs by selling public assets,laying off workers which resulted in mass unemployment.To escape from this,will take alot of effort and mobilisation of masses to the streets of,first of all in developed Countries and then others will follow.But if it’s started by/from poor Countries,it would be spinned as political uprisings and therefore lose the intended message.So the question is,how shall we (the population) change this without the message being misunderstood or lost in political misrepresentation?