There’s never been a more clear-cut case for reparations, says Marlene Daut.

(Bibliotheque Nationale de France)

By Marlene Daut

University of Virginia

In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, there have been calls for defunding police departments and demands for the removal of statues. The issue of reparations for slavery has also resurfaced.

In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, there have been calls for defunding police departments and demands for the removal of statues. The issue of reparations for slavery has also resurfaced.

Much of the reparations debate has revolved around whether the United States and the United Kingdom should finally compensate some of their citizens for the economic and social costs of slavery that still linger today.

But to me, there’s never been a more clear-cut case for reparations than that of Haiti.

I’m a specialist on colonialism and slavery, and what France did to the Haitian people after the Haitian Revolution is a particularly notorious examples of colonial theft. France instituted slavery on the island in the 17th century, but, in the late 18th century, the enslaved population rebelled and eventually declared independence. Yet, somehow, in the 19th century, the thinking went that the former enslavers of the Haitian people needed to be compensated, rather than the other way around.

Just as the legacy of slavery in the United States has created a gross economic disparity between black and white Americans, the tax on its freedom that France forced Haiti to pay – referred to as an “indemnity” at the time – severely damaged the newly independent country’s ability to prosper.

Cost of Independence

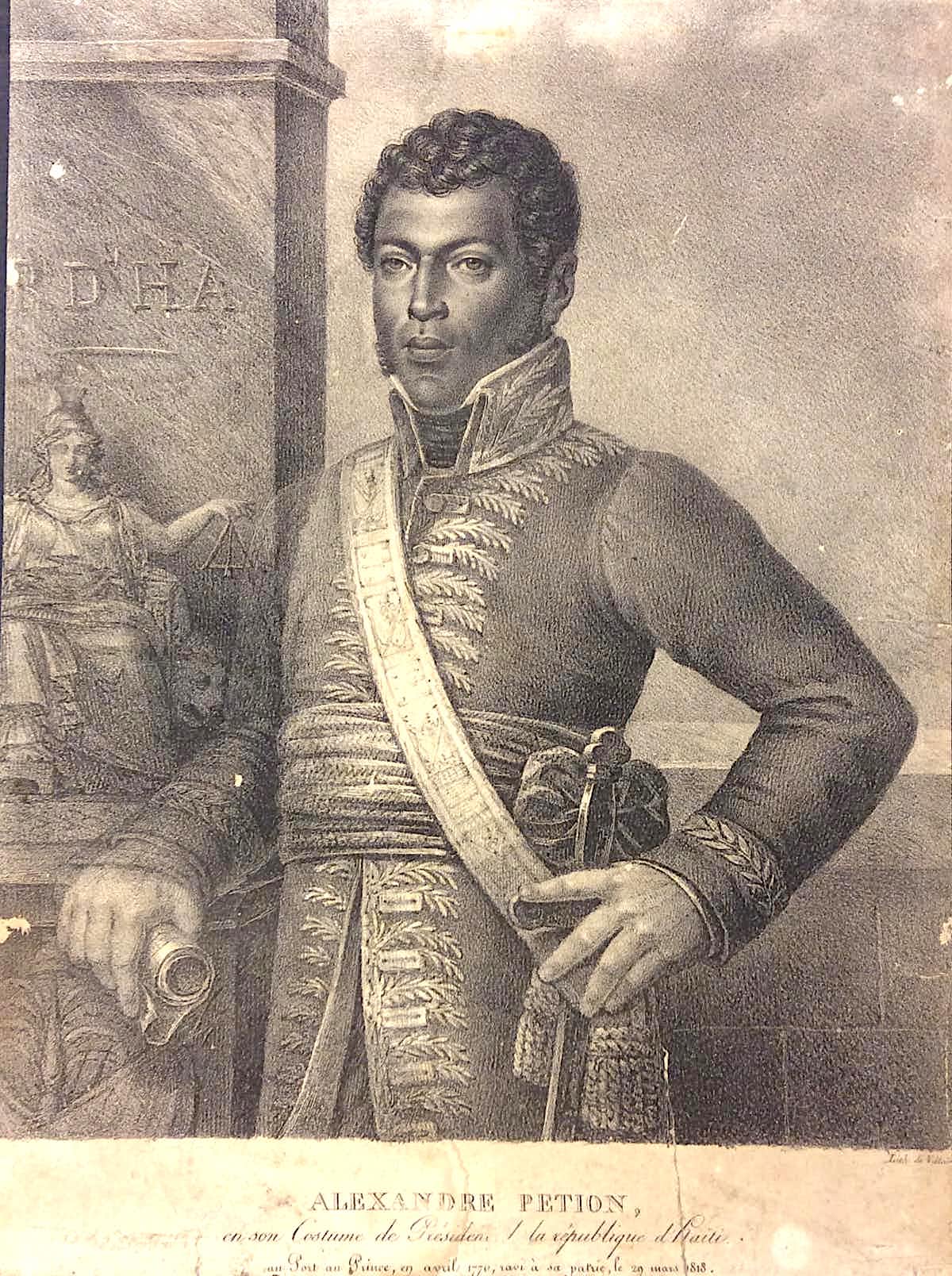

Haiti officially declared its independence from France in 1804. In October 1806, the country was split into two, with Alexandre Pétion ruling in the south and Henry Christophe ruling in the north.

Despite the fact that both of Haiti’s rulers were veterans of the Haitian Revolution, the French had never quite given up on reconquering their former colony.

In 1814 King Louis XVIII, who had helped overthrow Napoléon earlier that year, sent three commissioners to Haiti to assess the willingness of the country’s rulers to surrender. Christophe, having made himself a king in 1811, remained obstinate in the face of France’s exposed plan to bring back slavery. Threatening war, the most prominent member of Christophe’s cabinet, Baron de Vastey, insisted,“ Our independence will be guaranteed by the tips of our bayonets!”

(Alfred Nemours Archive of Haitian History, University of Puerto Rico)

In contrast, Pétion, the ruler of the south, was willing to negotiate, hoping that the country might be able to pay France for recognition of its independence.

In 1803, Napoléon had sold Louisiana to the United States for 15 million francs. Using this number as his compass, Pétion proposed paying the same amount. Unwilling to compromise with those he viewed as “runaway slaves,” Louis XVIII rejected the offer.

Pétion died suddenly in 1818, but Jean-Pierre Boyer, his successor, kept up the negotiations. Talks, however, continued to stall due to Christophe’s stubborn opposition.

“Any indemnification of the ex-colonists,” Christophe’s government stated, was “inadmissible.”

Once Christophe died in October 1820, Boyer was able to reunify the two sides of the country. However, even with the obstacle of Christophe gone, Boyer repeatedly failed to successfully negotiate France’s recognition of independence. Determined to gain at least suzerainty over the island – which would have made Haiti a protectorate of France – Louis XVIII’s successor, Charles X, rebuked the two commissioners Boyer sent to Paris in 1824 to try to negotiate an indemnity in exchange for recognition.

On April 17, 1825, the French king suddenly changed his mind. He issued a decree stating France would recognize Haitian independence but only at the price of 150 million francs – or 10 times the amount the U.S. had paid for the Louisiana territory. The sum was meant to compensate the French colonists for their lost revenues from slavery.

Baron de Mackau, whom Charles X sent to deliver the ordinance, arrived in Haiti in July, accompanied by a squadron of 14 brigs of war carrying more than 500 cannons.

Rejection of the ordinance almost certainly meant war. This was not diplomacy. It was extortion.

With the threat of violence looming, on July 11, 1825, Boyer signed the fatal document, which stated, “The present inhabitants of the French part of St. Domingue shall pay … in five equal installments … the sum of 150,000,000 francs, destined to indemnify the former colonists.”

French Prosperity Built on Haitian Poverty

Newspaper articles from the period reveal that the French king knew the Haitian government was hardly capable of making these payments, as the total was more than 10 times Haiti’s annual budget. The rest of the world seemed to agree that the amount was absurd. One British journalist noted that the “enormous price” constituted a “sum which few states in Europe could bear to sacrifice.”

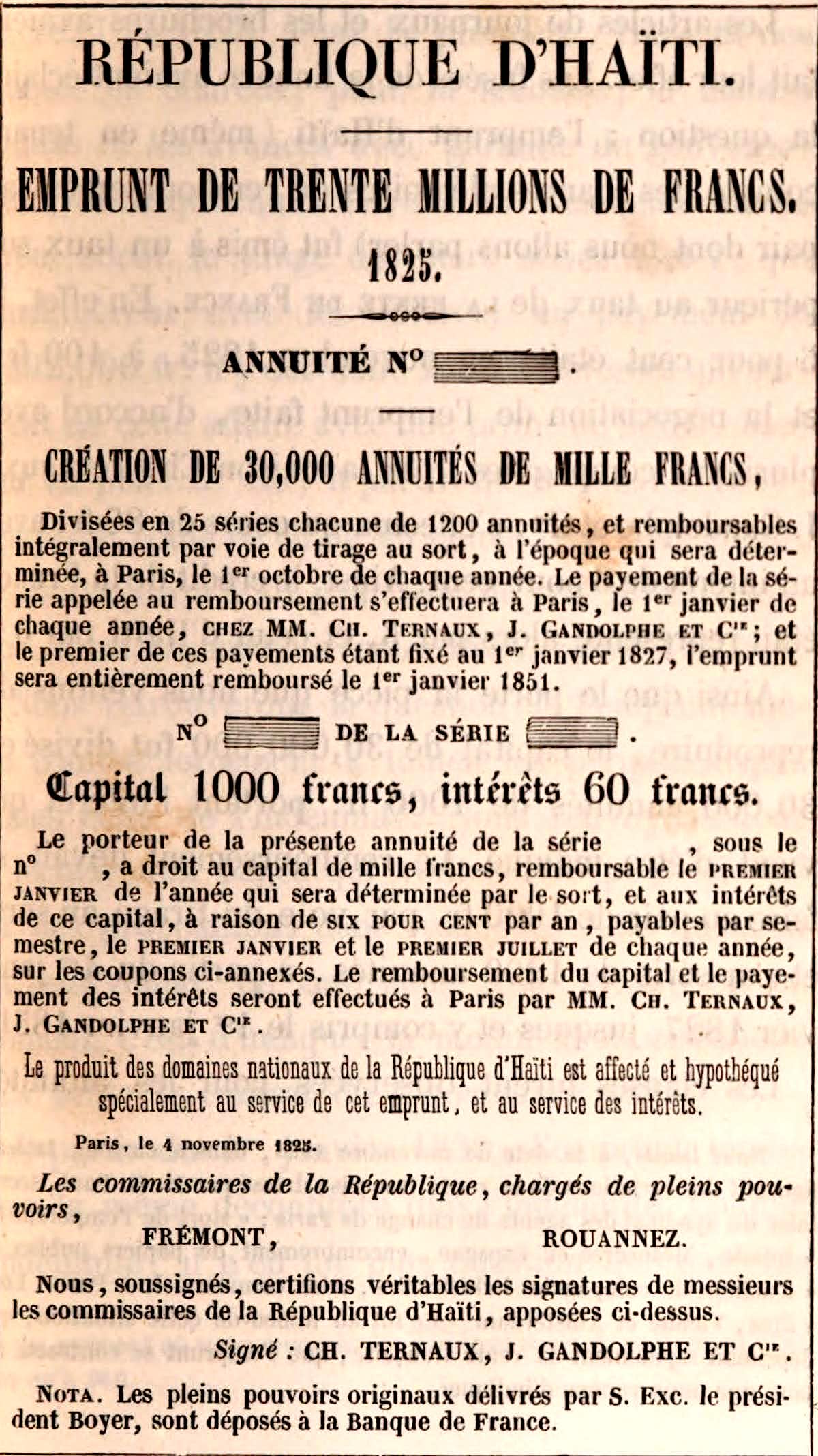

(Lepelletier de Saint-Remy, ‘Étude Et Solution Nouvelle de la Question Haïtienne.’)

Forced to borrow 30 million francs from French banks to make the first two payments, it was hardly a surprise to anyone when Haiti defaulted soon thereafter. Still, the new French king sent another expedition in 1838 with 12 warships to force the Haitian president’s hand. The 1838 revision, inaccurately labeled “Traité d’Amitié” – or “Treaty of Friendship” – reduced the outstanding amount owed to 60 million francs, but the Haitian government was once again ordered to take out crushing loans to pay the balance.

Although the colonists claimed that the indemnity would only cover one-12th the value of their lost properties, including the people they claimed as their slaves, the total amount of 90 million francs was actually five times France’s annual budget.

The Haitian people suffered the brunt of the consequences of France’s theft. Boyer levied draconian taxes in order to pay back the loans. And while Christophe had been busy developing a national school system during his reign, under Boyer, and all subsequent presidents, such projects had to be put on hold. Moreover, researchers have found that the independence debt and the resulting drain on the Haitian treasury were directly responsible not only for the underfunding of education in 20th-century Haiti, but also lack of health care and the country’s inability to develop public infrastructure.

Contemporary assessments, furthermore, reveal that with the interest from all the loans, which were not completely paid off until 1947, Haitians ended up paying more than twice the value of the colonists’ claims. Recognizing the gravity of this scandal, French economist Thomas Piketty acknowledged that France should repay at least $28 billion to Haiti in restitution.

Debt That’s Both Moral & Material

Former French presidents, from Jacques Chirac, to Nicolas Sarkozy, to François Hollande, have a history of punishing, skirting or downplaying Haitian demands for recompense.

In May 2015, when French President François Hollande became only France’s second head of state to visit Haiti, he admitted that his country needed to “settle the debt.” Later, realizing he had unwittingly provided fuel for the legal claims already prepared by attorney Ira Kurzban on behalf of the Haitian people – former Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide had demanded formal recompense in 2002 – Hollande clarified that he meant France’s debt was merely “moral.”

To deny that the consequences of slavery were also material is to deny French history itself. France belatedly abolished slavery in 1848 in its remaining colonies of Martinique, Guadeloupe, Réunion and French Guyana, which are still territories of France today. Afterwards, the French government demonstrated once again its understanding of slavery’s relationship to economics when it took it upon itself to financially compensate the former “owners” of enslaved people.

The resulting racial wealth gap is no metaphor. In metropolitan France 14.1 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. In Martinique and Guadeloupe, in contrast, where more than 80 percent of the population is of African descent, the poverty rates are 38 percent and 46 percent, respectively. The poverty rate in Haiti is even more dire at 59 percent. And whereas the median annual income of a French family is $31,112, it’s only $450 for a Haitian family.

These discrepancies are the concrete consequence of stolen labor from generations of Africans and their descendants. And because the indemnity Haiti paid to France is the first and only time a formerly enslaved people were forced to compensate those who had once enslaved them, Haiti should be at the center of the global movement for reparations.![]()

Marlene Daut is professor of African diaspora studies at the University of Virginia.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Please Contribute to Consortium

News on its 25th Anniversary

It’s an appalling injustice and crime against the Haitian people. It’s an important point you make that the damage caused manifests in the lack of resources of infrastructure and education. There’s a lot of competition for the title of greatest heist in history, there are some parallels with the TARP bailout for the banks, while I’m not comparing it to slavery. But the richest bankers were bailed out, and the economic hit has manifested in a destruction of our education system and infrastructure, while the actual criminals basically looted the taxpayers to get even richer. Clearly it has arrested the development of the country just like it happened to Haiti. In recent weeks in fact America does not look any more civilized or advanced than Haiti, even worse at times. I wonder how many times this pattern has repeated in history. Consider Monsieur Sarkozy, one of the most pro-Israel politicians whose Jewish father had him raised in the wealthiest suburb of Paris, Neuilly-sur-Seine, and when he gets the power of the state, punishes the poor Haitians, but rewards Israel and bankers with every favor within his power. The disproportional application of force or law and order or justice is so twisted and grotesquely unfair, when a man like George Floyd is murdered, and Eric Garner for the crime of a cigarette or two possibly not paid for, or taxed properly. And the rich have elevated their tax evasion to an art form. But for Sarkozy, his country’s debt of $28,000,000,000 to the Haitians is no problema in his mind, unpaid, unenforced, and ignored and downplayed?! People better wise up and learn their history before we are all in a kind of neo-colonial slavery-like system.

“Mr. Wendal has tried to warn us about our ways

But we don’t hear him talk”

– Mr. Wendal – Arrested Development

This goes in another direction, but given the sins of our own country, I wonder what we should really be teaching our children in school about the founding of our country. After so many years our chickens are coming home to roost in many ways (As are the chickens in other countries like France, etc.). So, what should we teach our kids about American history that would make us and them proud to be American?

History is replete with one country/empire/nation after another taking over another’s land, creating slavery, and, creating good things as well. And us, too.

So, what do we teach?

Reparations…pay all you want, as long as you want…you still will never pay the debt.

A couple of additional comments and a correction:

* By the time the US and French slave trades ended, French slave-traders had actually transported three times as many African slaves to the New World as US slave-traders had. This is another fun fact to point out to Frenchmen when they start getting holier-than-thou about American slavery.

* When the Brits abolished slavery in their empire, they, too, compensated the former slave-holders for their loss of property instead of the former slaves for their stolen freedom and labor — though I don’t know whether the Brits had the gall to demand that the former slaves directly pay for it.

* Martinique, Guadeloupe, Réunion, and French Guyana are not territories but have been overseas entities fully integrated into the French metropolitan political structure since the end of World War II. The nomenclature has varied over time, but since 2015, Guadeloupe and Réunion are “overseas single-department regions” with the same standing as metropolitan regions, and Martinique and French Guyana are “unique overseas communities” where there is greater leeway in adapting national law to local circumstances. But to my knowledge, even French overseas territories proper, one step further down in status, are represented in the national legislature — unlike Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guam, the Northern Marianas, and American Samoa. (I don’t know whether they’re fairly/proportionately represented, but their representatives can vote.)

When Napoleon tried to crush the revolt, he found a willing helper in President Thomas Jefferson who extended the French considerable assistance.

Jefferson was very much a racist, as he pretty much confessed in his Notes on Virginia and in letters.

He hated the notion of a black, ex-slave state being created.

It seemed to him like a real threat to the established order, an order which very much included Jefferson’s more than 200 slaves who provided him with an income since he never did earn a living.

He saw himself as a great man of leisure, like an English noble.

Napoleon’s effort in Haiti was a disaster, perhaps largely because tropical disease decimated the army of 50,000 he sent.

“When Napoleon tried to crush the revolt, he found a willing helper in President Thomas Jefferson who extended the French considerable assistance.”

A fact I was not aware of, but important. Thanks for this information. Like the intervention of U.S. presidents in the Palestine/Israel situation.

Jefferson “never did earn a living.” He was president of the United States. Can one say that leaders of nations don’t earn a living? Like Trump, Johnson, Macron, Putin, Xi, etc?

Yes, Jefferson was a hypocrite that fathered children with his slave, Sally Hemmings. Yes he, like you and I, was not perfection on earth, but your shot “…he never did earn a living” falls right in line with the current scourge being promoted in large part by the mainstream media. Perhaps we should sand-blast Jefferson from Mount Rushmore?

Despite any imperfections exhibited, for my money, Jefferson’s principle authorship of the Declaration of Independence ALONE guarantees his place among the greatest figures who contributed what is most admirable in Human History. Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water, John Chuckman.

“The resulting racial wealth gap is no metaphor. In metropolitan France 14.1 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. In Martinique and Guadeloupe, in contrast, where more than 80 percent of the population is of African descent, the poverty rates are 38 percent and 46 percent, respectively. The poverty rate in Haiti is even more dire at 59 percent. And whereas the median annual income of a French family is $31,112, it’s only $450 for a Haitian family.”

Don’t expect our current French président de la Républic Macron to repair the great damage done to Haiti. After all he is a Juan Guaido groupie, and hates the current government of Venezuela, while showing no interest in Haiti. In France he continues violent repression of demonstrations in favor of basic improvements in health care, working conditions, etc. And the median annual income of a French family is heading in the wrong direction.

In response to your response above.

President of the US, yes, that’s eight years out of a long life.

Jefferson borrowed heavily from friends and died without ever having paid them back. He died a bankrupt.

He kept his slaves to the end, and of course they were sold off after his death.

He had an unquenchable thirst for luxuries. New silver buckles for his shoes. New model carriages. The latest this or that. He had ice cream made at Monticello and kept cold in his 150 foot deep specially-built stone-lined well where he kept ice.

His mistress, after his wife died, was a thirteen-year old slave named Sally Hemmings.

Some say she resembled his wife because she was fathered by his wife’s father.

Such were the horrors of slave society.

Jefferson was without question the biggest hypocrite of all the Founders.

See my stuff on Jefferson on my site for more.

I was many years ago an omnivorous reader of US history. I read eight biographies of Jefferson, including the majors.