UPDATED: Though it has a reputation of upholding international law, Norway has refused to ratify an amendment that adds the crime of aggression to the International Criminal Court.

Special to Consortium News

As Norway stood for election on Wednesday for a seat on the UN Security Council, Nuremberg prosecutor Benjamin Ferencz lambasted what he called “Norwegian hypocrisy” for failing, so far, to support an amendment to the statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) that would include the crime of aggression, which the Nuremberg Trials deemed the worst of all war crimes.

Ferencz, who led the prosecution of German Nazi leaders responsible for the extermination of Jews during World War II, has been a fierce advocate for the amendment to the Rome Statute that would grant the ICC jurisdiction to prosecute leaders responsible for the crime of aggression. The amendment entered into force in 2018 and has so far been ratified by 39 states, including the majority of NATO member countries.

Norway, however, is notably absent from the list.

“The maintenance of international peace and security” is the central purpose of the Security Council. In a letter sent to a Norwegian newspaper, Ferencz expressed, in no uncertain terms, what he sees as the striking contradiction of Oslo seeking to occupy a Council seat while failing to support the amendment to punish the crime of aggression. That crime is defined as an unprovoked attack on a nation, without the justification of self-defense.

“It does not take much imagination to recognize that nations which profess their support for criminalizing aggression but which fail to take the steps necessary to apply such laws to their own citizens run the very real risk of being perceived as hypocrites, or worse,” Ferencz wrote.

Though Norway is generally perceived as a champion of peace and international law, the country has drifted closer to the U.S. government since 1999 when it began participating in a series of U.S. and NATO-led wars.

Among them were military interventions against Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and most notably Libya, where Norway dropped 588 bombs and struck targets other NATO countries were reluctant to attack because of a high risk to civilians. Three years later, then Norwegian Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg was awarded the post of NATO Secretary General.

US Hostility to the ICC

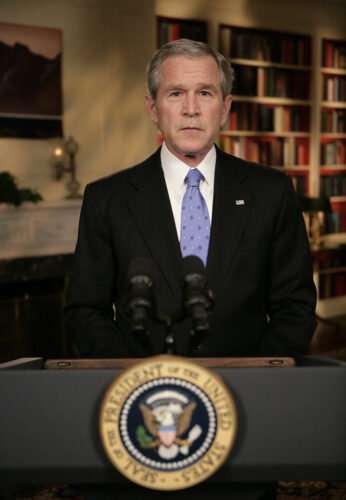

The U.S. has refused to join the ICC. The court’s treaty was signed by President Bill Clinton but was never ratified by the Senate. President George W. Bush “unsigned” it and since then the U.S. has taken measures to undermine the court and protect itself from ICC prosecution.

Nations are liable to prosecution if they commit alleged war crimes, crimes against humanity or genocide only if they are members of the court or if an alleged crime is committed on the territory of a court member, even by a non-member state. For instance, after a preliminary report found reason to believe the U.S. committed war crimes in Afghanistan, which is a member of the court, the ICC opened a formal investigation.

The Trump administration responded last week by imposing sanctions on officials of the ICC. The executive order freezes the officials’ assets in the U.S. and bars them from entering the country. The ICC responded by calling the move an “unacceptable attempt to interfere with the rule of law.”

During the Bush administration, the U.S. pressured nations with a cutoff of aid if they did not conclude bilateral agreements giving immunity from prosecution to U.S. military personnel. Congress at the time passed into law the infamous Invade Hague Act, which gives the U.S. permission to intervene militarily in the Dutch city that hosts the ICC to free any U.S. service members being held by the court.

Unlike the U.S., the Norwegian government is a signatory to the Rome Statute and proclaims itself “one of the main backers” of the ICC. In 2010 Norway promised ratification of the Kampala amendment, granting the ICC jurisdiction over the crime of aggression. But it has never followed through. Ferencz declared to the Norwegian newspaper Dagsavisen that “after making such promises, states that fail to ratify the amendment look like hypocrites.”

Hardly anyone today speaks with more moral authority knowledge and experience than Fernecz on how to protect human beings from the horrors of war –and how not to do it, which makes his attack on the Norwegian position all the more remarkable.

In the Nuremberg trial, war of aggression was defined as the supreme international crime, surpassing even the most heinous crimes committed by the Nazis against their victims. Chief American prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson, said at the time:

“To initiate a war of aggression, therefore, is not only an international crime; it is the supreme international crime differing only from other war crimes in that it contains within itself the accumulated evil of the whole.”

While Western governments tend to portray military intervention as a tool for preventing other crimes, Ferencz maintains that war of aggression is more likely to provoke war crimes, genocide and crimes against humanity than to prevent them.

Avoiding Debate

The Norwegian government has so far mostly shunned making public statement revealing its stance on the criminalization of war of aggression. Hence, Norway has avoided international debate about its hitherto failure to ratify the amendment as the Security Council election nears. Norway is running against Ireland and Canada for the two European seats on the Council. [Norway and Ireland were elected on Wednesday.]

This might change, however, as a proposal urging the ratification of the amendment, was introduced in parliament just before the corona crisis hit Norway and paralyzed most parliamentary activity. The private members bill was drafted by MP Bjørnar Moxnes of the left-wing Red Party. When it comes due for debate and parliamentary vote during the coming months, the bill will force the government to show its hand, voting either in favor or against ratification.

Asked by Dagsavisen earlier this year why Norway has still not accepted the amendment prohibiting aggression, the state secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs was non-committal. “The question of Norwegian ratification of the crime of aggression raises a series of questions of principle that will have to be assessed thoroughly before Norway can decide on future ratification,” he said. Though ambiguous, the comment seemed to leave the door open for ratification.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’ 25th Anniversary

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

Imagine being born, raised and living in a fictional place called “My Home Town” where efforts to maintain some semblance of law and order suffered from non-universality, i.e. 98% of the citizens observed My Home Town’s legal system while 2% ignored the laws and carried out serious crimes with impunity for many generations.

Imagine being born, raised and living on a REAL planet called Earth … Wars of aggression persist while immunity for war criminals persists, making abundantly and painfully clear the paramount challenge facing humanity: once and for all establishing a rock-solid global legal institution fully effective in ending impunity for war criminals and raising deterrence against war crimes sufficient for all intents and purposes to end criminal wars, forever.

A relatively simple reform mandating member states of the United Nations to agree upon International Criminal Court global jurisdiction for criminal matters of war and peace would arguably accomplish the goal civilization has been wishing for ever since time began: ending wars and establishing true, lasting, forever peace on Earth.

To embarrass reluctant or refusing United Nations member states to do the right thing and join the International Criminal Court, a stipulation in the reform language could easily overcome such challenges. Any nation(s) refusing to join the Court must leave the United Nations organization – until such time said member state(s) come to their senses, and wisely choose to act for peace..

For this and future generations…

Johan Galtung, the Norwegian professor of peace, was once asked about the foreign policy of Norway. What policy, he said, it is just a copy of the US foreign policy!

As a Norwegian I have lived my entire life under the US initiated cold war. And our most important party, The Labour party, has always been in front in making Norway a US vassal state, with its most important politician for decades being Jens Stoltenberg.

In October 2001 Stoltenberg’s government approved NATO using article 5 for starting the war on terror. Think about this: A leader with personal integrity would demand solid evidence from the US about the reason to invade Afghanistan. They did not ask, of course. Look at the “evidence” they were presented at The NATO council:

hXXps://motstraumen.wordpress.com/2019/04/27/the-mysterious-frank-taylor-report-the-9-11-document-that-launched-us-natos-war-on-terrorism-in-the-middle-east/

A good corrective to current hagiographies that praise Norway for its climate fund, foreign aid, and willingness to vote against Israel at the General Assembly. So Norway too has heavy feet of clay.

However, Norway’s negative role in the world doesn’t compare to Canada’s reactionary record. Canada too is a NATO member, and led the projection of the ‘Right to Protect’ that NATO used as a fig leaf to cover its destructive attack on Libya. Canada bombed even more than Norway in that campaign, and had previously bombed Serbia with NATO, and joined in the U.S.-led Desert Storm attack on Iraq in 1990. And despite its official reluctance to join Bush II’s 2003 invasion of Iraq, Canada supported that attack in several ways, including two years later relieving U.S. forces in the most contested area of Afghanistan (leading to 159 Canadian deaths). Canada has generally been a tool of Israel and U.S. Zionists in opposing votes for Palestinian rights.

So progressives, including in Canada, are relieved that Norway and Ireland defeated Canada in General Assembly voting for a Security Council seat today — though the margin of loss should have been more decisive.

I think Norway made a terrible mistake by participating in these interventions/wars of USA/NATO. Justifications for war is nothing new but war is war. It means death and suffering for the target population, disproportionately affecting the poor and disadvantaged. I don’t understand how any Norwegian politician has the nerve to inflict that on other countries that are no threat to our safety. The bottom line for me is that I will never vote for any politician or party that has supported foreign interventions or war participation.

To be honest though, Norway has not had a spotless record in international events recently. We failed to assert our position on Human Rights in the face of losing access to the Chinese markets. We chose money over principles.

The Court should remind criminal regimes like Israel, the US and UK that the Nazis wouldn’t have ratified Nuremberg either but they still ended up there. Likewise, these rogue regimes don’t have to ratify the ICC because they’re already on it.

You wrote ,” I’m sure Norway doesn’t plan to invade another country unless it becomes an existential necessity. ” Did you miss this part?: “Since 1999… it began participating in a series of U.S. and NATO-led wars.

Among them were military interventions against Yugoslavia, Afghanistan and most notably Libya, where Norway dropped 588 bombs and struck targets other NATO countries were reluctant to attack because of a high risk to civilians. “

Agression is eeverywhere.

Warfare is something else.

Of course Norway is hypocritical.

Great article! But a minor editorial quibble on the “supreme war crime” quote attributed to Chief American prosecutor, Robert H. Jackson. Jackson first uttered it on the record, but it was adopted as part of the Court’s judgment, which makes it case law rather than just a statement by a prosecutor. Therefore, the attribution to the judgment should be preferred. See Reading of the Judgment, 22 Nuremberg Trial Proceedings 427 (30 September 1946), hXXp://avalon.law.yale.edu/imt/09-30-46.asp.

It is somewhat ironic that Prof Noam Chomsky is accused of being an anarchist and in a way they are right in that an anarchist believes that all states should adhere to some form of international law.

So you end up with Russia being accused of aggression over Crimea where there was an election and they were invited in but when it came to Afghanistan, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Syria, Libya and others bu the US and its vassal states no such charge was made.

My vote would go to Cuba.

While I support the author’s point about the ICC, I think there is another, more glaring objection to Norway.

And that is its NATO membership.

That renders it just an echo of American foreign policy, and the Security Council already has servile Britain and France.

The UN is supposed to represent something of the other over 95% of humanity who are not Americans.

NATO’S Secretary General, the creepy Jens Stoltenberg, is a former hack Norwegian politician too.

Thank you for this most informative & serious article about the importance of Norway upholding its responsibility to the ICC Court. Without its ratification, we are indeed all doomed to WW3!! It appears this is the chosen path of the US, with its brazen & arrogant sanctions against the ICC itself! It is apparent that the US has every intention of continuing its wars of aggression & all ICC members must stand together to block this threat to world peace!!

It would be logical as well as morally correct for Norway (population 5.4 million) to ratify the amendment that makes national aggression a crime at the International Criminal Court. I’m sure Norway doesn’t plan to invade another country unless it becomes an existential necessity. Of course Norwegians Know the situation in their neighborhood better than others and will do the right thing for Norway.

The world knows that a large majority of Norwegians oppose aggressive acts and aggressive war. On that democratic basis the current US government should also ratify the ICC amendment.

BTW the non-permanent members of the Security Council should be randomly chosen from a database of members. None serving twice until all have had the opportunity to serve once. None serving three times until all members have had the opportunity to serve twice. And so on maintaining an equal opportunity among non-permanent members. The permanent SC members should not be able to influence non-permanent members before the process even starts.

> I’m sure Norway doesn’t plan to invade another country unless it becomes an existential necessity.

You should read the article more carefully! As it states, Norway, along with other NATO members, has done so several times in the last few years. And the former Prime Minister, Jens Stoltenberg, has been an open advocate of every pernicious NATO policy, including nuclear war, as NATO Secretary-General.