On May Day, Americans were more aware of the plight of workers than at any time in decades, argues Peter Dreier.

By Peter Dreier

Common Dreams

Unlike the rest of the world’s democracies, the United States doesn’t use the metric system, doesn’t require employers to provide workers with paid vacations, hasn’t abolished the death penalty and doesn’t celebrate May Day as an official national holiday.

Unlike the rest of the world’s democracies, the United States doesn’t use the metric system, doesn’t require employers to provide workers with paid vacations, hasn’t abolished the death penalty and doesn’t celebrate May Day as an official national holiday.

Outside the U.S., May 1 is international workers’ day, observed with speeches, rallies and demonstrations in Asian, Latin America, Europe, Africa, Australia, and Canada. This year, the global COVID-19 pandemic will keep most workers around the world in their homes rather than, in a typical year, taking to the streets to demand higher wages, better benefits and improved working conditions.

But on this May Day, Americans were more aware of the plight of workers than at any time in decades. Despite the Trump administration’s incompetence and indifference in handling the virus crisis and the economic collapse, the courage and resilience of front-line health care workers, grocery store and drug store employees, farmworkers and food processing workers, and many others are in the news.

Trump’s demands that workers in dangerous and vulnerable jobs—such as meat-processing factories—return to work as “essential” employees, without guaranteeing adequate safety measures, is yet another example of why we need a stronger labor movement.

“International celebration of working-class solidarity was started by the U.S. labor movement and soon spread around the world, but it never earned official recognition in this country.”

No sector has been more disrupted by the current crisis than the tourism and sports industries, where millions of hotel, restaurant, stadium, and sports arena workers have lost their jobs. Two weeks ago, the labor movement in Los Angeles—which is heavily dependent on tourism—won a big victory by the City Council passed an ordinance by a 15-0 vote to require those businesses to offer jobs in the hospitality and other sectors to their former employees, based on seniority, at their existing wage levels, once they start rehiring.

The measure will guarantee that workers are not replaced by newer, cheaper labor once the economy rebounds. The hotel workers union, UNITE HERE, the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, and the Los Angeles County Federation of Labor spearheaded the campaign for the law. That coalition will now seek to get the state legislative to adopt a similar bill.

But no other cities or states have so far adopted similar laws, leaving laid off workers—33 million have already applied for unemployment insurance—vulnerable to further trauma even after the economy recovers.

Indeed, the current crisis has exposed the fragility of the nation’s economy, health care, and housing systems, and could—some progressive activists insist—lead to a dramatic rethinking of what the country should be doing to improve living and working conditions for America’s families. That’s precisely what the nation’s radical movement was thinking in the late 19th Century when they first developed the idea for May Day.

Yes, this international celebration of working-class solidarity was started by the U.S. labor movement and soon spread around the world, but it never earned official recognition in the United States.

US Origins of May

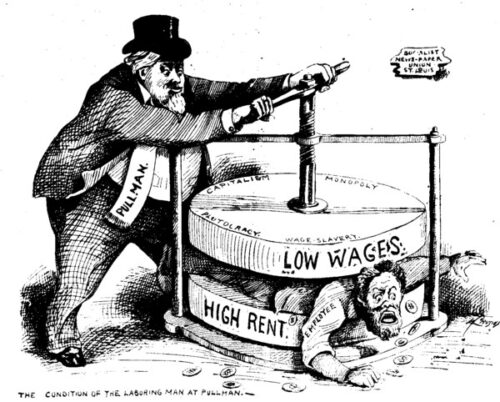

The original May Day was born of the movement for an eight-hour workday. After the Civil War, unregulated capitalism ran rampant in America. It was the Gilded Age, a time of merger mania, increasing concentration of wealth and growing political influence by corporate power brokers known as Robber Barons. New technologies made possible new industries, which generated great riches for the fortunate few, but at the expense of workers, many of them immigrants, who worked long hours, under dangerous conditions, for little pay.

As the gap between the rich and other Americans widened dramatically, workers began to resist in a variety of ways. The first major wave of labor unions pushed employers to limit the workday to 10, then eight, hours. The 1877 strike by tens of thousands of railroad, factory and mine workers — which shut down the nation’s major industries and was brutally suppressed by the corporations and their friends in government — was the first of many mass actions to demand living wages and humane working conditions.

By 1884, the campaign had gained enough momentum that the predecessor to the American Federation of Labor adopted a resolution at its annual meeting, “that eight hours shall constitute legal day’s labor from and after May 1, 1886.”

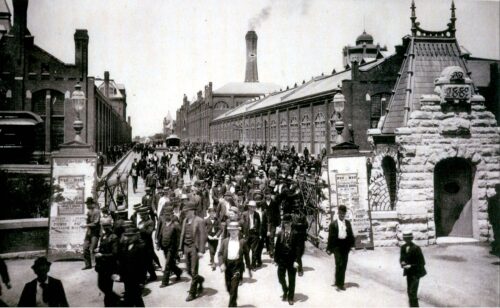

On the appointed date, unions and radical groups orchestrated strikes and large-scale demonstrations in cities across the country. More than 500,000 workers went on strike or marched in solidarity and many more people protested in the streets. In Chicago, a labor stronghold, at least 30,000 workers struck. Rallies and parades across the city more than doubled that number, and the May 1 demonstrations continued for several days.

The protests were mostly nonviolent, but they included skirmishes with strikebreakers, company-hired thugs and police.

On May 3, at a rally outside the McCormick Harvesting Machine Company factory, police fired on the crowd, killing at least two workers. The next day, at a rally at Haymarket Square to protest the shootings, police moved in to clear the crowd. Someone threw a bomb at the police, killing at least one officer. Another seven policemen were killed during the ensuing riot, and police gunfire killed at least four protesters and injured many others.

After a controversial investigation, seven anarchists were sentenced to death for murder, while another was sentenced to 15 years in prison. The anarchists won global notoriety, being seen as martyrs by many radicals and reformers, who viewed the trial and executions as politically motivated.

US Workers Inspired the World

Within a few years, unions and radical groups around the world had established May Day as an international holiday to commemorate the Haymarket martyrs and continue the struggle for the eight-hour day, workers’ rights and social justice.

In the U.S., however, the burgeoning Knights of Labor, uneasy with May Day’s connection to anarchists and other radicals, adopted another day to celebrate workers’ rights. In 1887, Oregon was the first state to make Labor Day an official holiday, celebrated in September. Other states soon followed.

Unions sponsored parades to celebrate Labor Day, but such one-day festivities didn’t make corporations any more willing to grant workers decent conditions. To make their voices heard, workers had to resort to massive strikes, typically put down with brutal violence by government troops.

In 1894, the American Railway Union, led by Eugene Debs, went on strike against the Pullman Palace Car Company to demand lower rents (Pullman was a company town that owned its employees’ homes) and higher pay following huge layoffs and wage cuts. In solidarity with the Pullman workers, railroad workers across the country boycotted the trains with Pullman cars, paralyzing the nation’s economy, as well as its mail service.

President Grover Cleveland declared the strike a federal crime and called out 12,000 soldiers to break the strike. They crushed the walkout and killed at least two protesters. Six days later, Cleveland—facing worker protests for his repression of the Pullman strikers—signed a bill creating Labor Day as an official national holiday in September. He hoped that giving the working class a day off to celebrate one Monday a year might pacify them.

For most of the 20th century, Labor Day was reserved for festive parades, picnics and speeches sponsored by unions in major cities. But contrary to what President Cleveland had hoped, American workers, their families and allies, found other occasions to mobilize for better working conditions and a more humane society.

America witnessed massive strike waves throughout the century, including militant general strikes and occupations in 1919 (including a general strike in Seattle), during the Depression (the 1934 San Francisco general strike, led by the longshoremen’s union; a strike of about 400,000 textile workers that same year; and militant sit-down strikes by autoworkers in Flint, Michigan, women workers at Woolworth’s department stores in New York, aviation workers in Los Angeles and others in 1937) and 1946 (which witnessed the largest strike wave in U.S. history, triggered by pent-up demands following World War II). The feminist, civil rights, environmental, and gay rights movements drew important lessons from these labor tactics.

Meanwhile, May 1 faded away as a day of protest. From the 1920s through the 1950s, radical groups, including the Communist Party, sought to keep the tradition alive with parades and other events, but the mainstream labor movement and most liberal organizations kept their distance, making May Day an increasingly marginal affair.

In 1958, during the Cold War, President Dwight Eisenhower proclaimed May 1 as Loyalty Day. Each subsequent president has issued a similar proclamation, although few Americans know about or celebrate the day.

Reviving May Day

In 2006, some U.S. unions and immigrant rights groups resurrected May Day as an occasion for protest. That year, millions of people in over 100 cities—including more than a million in Los Angeles, 200,000 in New York and 300,000 in Chicago—participated in May Day demonstrations. Each year since, immigrant workers and their allies have adopted May Day as an occasion for protest.

“America is now in the midst of a new Gilded Age with a new group of corporate Robber Barons, many of them operating on a global scale.”

America is now in the midst of a new Gilded Age with a new group of corporate Robber Barons, many of them operating on a global scale. The top of the income scale has the biggest concentration of income and wealth since 1928. Several decades of corporate-backed assaults on unions have left only seven percent of private sector employees with union cards.

More than half of America’s 15 million union members now work for government (representing 37 percent of all government employees), so business groups and conservative politicians have targeted public sector unions for destruction.

Last week Senator Majority Leader Mitch McConnell proposed, in a memo leaked to the press, that the federal government withhold funds to cities and states who are facing bankruptcy due to the closure of most businesses. His plan is designed to punish Democratic cities and states and bust public-sector unions, who are leading the fight against Trump and the Republicans.

Staging a Comeback

Over the past decade, while wages and living standards for the majority of Americans have declined, unions have started making a comeback. The idea of a $15 minimum wage was a pipe dream in 2010 but now is mainstream.

A Brookings Institution report released in November found that more than 53 million people, or 44 percent of all workers ages 18 to 64, earn low hourly wages. Many families need more than two jobs to make ends meet, including one-fifth of all schoolteachers. The new slogan for many unions is now “One job should be enough.”

Congress hasn’t increased the federal minimum wage ($7.25) since 2009, so activists have pushed the issue in cities and states. The Fight for $15 burst forward, with wildcat strikes at fast-food and retail outlets morphing into successful legislative initiatives and ballot campaigns.

According to the National Employment Law Project, 24 states and 48 cities and counties will raise their minimum wages sometime in 2020. In 32 of those jurisdictions, it will reach or surpass $15 per hour. Activists also pressured McDonald’s, Walmart, Disney, Bank of America, and other large employers into raising their pay scales.

The fight for higher wages has coincided with an upsurge of labor activism, including successful strikes by GM workers and teachers in red and blue states.

According to a recent Gallup poll, public support for unions reached a two-decade peak of 64 percent. There’s a growing demand for paid family leave—a policy that, had it been in place three months ago, would have lessened the suffering caused by the pandemic.

During the current election season, many Democratic politicians have called for a federal $15 minimum wage, unlinking health insurance from jobs, reform of labor laws to make it easier for workers to unionize, a requirement that workers elect representatives to serve on the boards of U.S. corporations.

Workers at Amazon, Walmart and other companies staged May Day one-day job actions on Friday. Renters around the country held a one-day rent strike. So while there may not have been big parades and mass protests this year to celebrate May Day, there was nothing to stop Americans joining together remotely to sing “Solidarity Forever.”

Of course Jared, I’m very happy to give you at least some alternatives to WSWS. I agree with what you say about the current state of the unions. Their leaderships are responsible for allowing things to go as far as they have and have been directly responsible for the historically low TU membership levels in the US (and elsewhere). After all, why in hell would anyone pay union dues only to see them transferred to the bourgeois Democrats, the class enemy, and not only pay for that privilege but to pay to be stabbed in the back by the pro-capitalist union misleadership when you dare to engage in a spot of class struggle?

Here’s an article on the (near) current UAW situation that I think is spot on:

www(dot)icl-fi.org/english/wv/1160/uaw.html

And here’s a little piece on the WSWS warning about their position on the TUs:

icl-fi(dot)org/english/wv/1162/wsws.html

WSWS to my knowledge have ever explicitly defended a union against attacks by the bosses and their state. And what would their position be on any efforts to unionise the South? Abstention? Or support for the bosses to prevent it happening (no doubt with the help of their rank-and-file committees)?

If you want to read further on the role trade unions in the imperialist epoch, I think this is a good place to start: www (dot) marxists(dot)org/archive/trotsky/1940/xx/tu.htm

And to give some direction to how revolutionaries and Marxists should be conceiving a strategy to win, this is the best place to start I can think of: www(dot)marxists(dot)org/archive/trotsky/1938/tp/transprogram.pdf

There’s more on trade unions in the latter as well. And all these very sensible writings by Trotsky on TUs (that WSWS would never publicly renounce) are in direct contradiction to their horrible TU position. That’s a circle they can’t square.

Finally, here’s two excellent pieces on when TUs in the US led did lead some struggles properly, in the 1930s:

www(dot)icl-fi(dot)org/english/wv/1050/then-and-now.html

www(dot)cl-fi(dot)org/english/wv/1051/then-and-now.html

I hope you can read (and critique) the above, and read further of course. The online Marxist archive (www.marxists.org) is an excellent resource.

Thanks for the reading. It definitely helps me understand the point of view of the Spartacus League / ICL-FI. You’ll have to forgive me if some of the following sounds naive, as I am certainly not as studied as you are, but I honestly I don’t understand the deep animosity between the ICL-FI and the WSWS / ICFI. They both seem to agree on just about everything with the exception of a few minor divergences. The hostility between the two, and I know that comes from both sides, seems unwarranted and needlessly exaggerated. Can’t some degree of political kinship be recognized among various Trotskyist parties without ignoring or compromising on important theoretical and tactical disputes? Is it really reasonable for the Spartacus League to slander the WSWS as a “dubious outfit” and “fake socialists” based solely on their position on unions?

As to the theory, some quick thoughts: what the ICFI seems to be pushing is bypassing the the unions and going straight to the creation of factory committees (isn’t that what a rank-and-file committee would be?). Both Trotsky and the ICL-FI agree that factory committees are more revolutionary than unions and act as a counter-weight to the bourgeois tendencies of the union bureaucracies. You are absolutely correct that WSWS position is a divergence from Trotsky. They should perhaps be a bit more forthright about that. But Trotsky was not infallible (after all, he wrote a essay using dialectic to excuse terrorism during the revolution, something every Trotskyist party should be more forthright about, IMO), and he did not have the benefit of the past 80 years of history. It seems entirely reasonable to me that there would be divergences so long as they can be justified.

Regardless, the best bit I got from the reading you suggested was about A.J. Muste who was a pacifist (like me), although a preacher (how a long for an atheist pacifist role model), who organized unemployed labor into Unemployment Leagues. I didn’t even know that was possible, but the organization of the unemployed and poor seems pretty revolutionary to me. And indeed, the article says it was critical support for the strikes in Toledo. I’m looking forward to reading more about that.

It’s instructive to note the dearth of media coverage re May Day strike actions.

Indeed, while all such actions have been essentially blackballed, heavy coverage of the Freedumb! Suicide Squad’s astroturf protest and intimidation continues apace.

Maybe this time, the capitalists will realize that there can’t be a healthy national economy, when working people can’t afford to pay for much except rent and food. Besides, the better the wages, the more money people have to spend. Even Henry Ford figured that out He paid the workers $5 and then— even the workers could even afford to buy one of the cars that they had built. That’s one way to make sure your own product makes a lot of sales. Corporations today have not seemed to be able to figure that out!

Another most important thing missing in the US, which is taken for granted in virtually all other ‘democracies’ and in many dictatorships as well, is a mass workers party. Not even a mildly reformist pro-capitalist one, let alone a revolutionary one needed to end the increasingly irrational and murderous rule of capital.

If you’re a capitalist, a one-day strike is a wonderful thing. You know in advance when the strike will end and there is no long-term threat to production. You give the workers a day to blow off steam and then send them back to work, pandemic viruses be damned. You can even force them to work overtime later on to make up for the lost day.

There are 65,000 dead and counting in the US from this virus. We are seeing death tolls higher than 2,000 per day. Amid these grim statistics, the capitalists and their lapdog unions permit a one-day strike while demanding the fastest possible return to work. Is a one-day strike a proportional response to the reckless and dangerous demand that workers sacrifice themselves by the tens of thousands on the altar of capitalist profit? Or, could it be a symbolic gesture to keep the rank-and-file in line? Do the unions intend to fight or do they intend to pretend? I’d call up the UAW and ask, but they seem to be tied up in federal court on account of taking millions of dollars in bribes from GM.

One last thing, the strike “successes” that the author mentions above were nothing of the sort. In both cases, the unions dropped key contract demands entirely and with the teachers even rushed through a last minute vote so that the rank-and-file would not have time to even read the contract (that’s how bad it was). Early this year the UAW sided with management against its own union members in the University of California COLA strikes. If we are concerned with improving the fate of the world’s workers, we owe it to ourselves to analyze carefully the political and economic role that the big unions are currently playing.

As you may be aware, some leftist currents see unions per se as being ‘structurally’ part of the rule of capital. The World Socialist Web site, which professes to be ‘Leninist’ and ‘Trotskyist’, is an example. Their ‘solution’ for sell-out union misleaders is rank-and-file committees as a substitute for unions. In reality advocating such committees serves as a substitute for the necessarily hard struggle to oust the current sellout pro-capitalist misleaders of the trade unions and replace them with a revolutionary leadership — to restore the unions to their original purpose as organs of class struggle and transform them into organised battalions of revolution.

Of course, anyone with any sense of history or experience of struggle can see that rank-and-file committees on their own are no substitute for the organisational strength and resources of a nationwide industrial union like the UAW. Nor did Lenin and Trotsky (or Zinoviev) in all their writings about the trade unions and the trade union bureaucracy ever advocate such a syndicalist outlook of ditching the trade unions in favour of syndicalist schemes of rank-and-file committees.

Instead, what’s needed is the transformation of the UAW and all the other currently misled unions by ousting their corrupt, bribe-taking leaderships. And the bourgeois state, its courts, cops, and prisons, have absolutely no business interfering in union affairs. The workers themselves must clean their own house and never allow the class enemy any opportunity to destroy near their hard-won organisations. The UAW and all trade unions must be defended from the class enemy, whether in the courts or on the picket lines — unconditionally.

To the naive, the trade unions today may appear to be joined at the hip with big business and as monolithic, appendages of the rule of capital without internal contradictions. But it’s their leaderships which are beholden to the capitalist class, and the unions can and must be taken away from these sellout misleaders when major class battles erupt. Such appear likely in the near future, and rank-and-file committees certainly have their place, especially to run the strikes and class battles as an important defense mechanism from sell out misleaders stabbing struggles in the back, but in the end it boils down to having a program to win. And any ‘program’ that professes the historic defense organisations of the working class to be hopelessly compromised and beyond redemption isn’t worth the paper it’s written on, or one single pixel of all the screens around the globe that it might appear on.

Hi Stephen. Thanks for the response. As you have clearly guessed, I am aware of the perspective on trade unions published by the WSWS, and have found it quite persuasive. Before I offer a few words in their defense, I want to point out something that I think is of critical importance: We both seem to agree that the “political and economic role” currently played by the big unions is not revolutionary and is instead subservient to the interests of capital. In other words, these “working class organizations” no longer represent the interests of workers. This is a fact that should be discussed far and wide, but you won’t hear a peep about it in any of the pseudo-left press or political parties including the DSA. They have adopted “unconditional” (and “uncritical”) support of the union bureaucracies, and celebrate every sellout contract as a “victory.”

The WSWS has been one of the few left perspectives I have found that even bothers to raise the issue and discuss the problem. There is value in that regardless of whether or not you agree with their solution. They suggest that we must build new workers organizations to supplant the old unions, starting with rank-and-file committees. My Marxist education has not progressed enough to offer any new or interesting insights in that regard, but I will say that the position is certainly far better grounded in history and theory than you give it credit. It was an article by David North titled “Why are trade unions hostile to socialism” that first made me sympathetic to the WSWS position. If you can suggest a more persuasive analysis of the historic role of unions than that, I would be very interested in reading it.