Despite Joe Biden’s recent pot shot at Italy’s struggling response to the pandemic, Andrew Spannaus says the Italian and U.S. medical systems have more in common than many realize.

Italian flag hung from a window in Bologna says “Andrà tutto bene” (Everything is gonna be fine) during the Covid-19 pandemic, March 2020. (Pietro Luca Cassarino, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By Andrew Spannaus

Special to Consortium News

During the March 15 Democratic presidential debate between Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, moderator Jake Tapper of CNN asked how to avoid a situation like that in Italy, where in some areas doctors are forced to decide who gets urgent treatment and who does not to survive the coronavirus. When it was Biden’s turn to answer, he said “With all due respect for Medicare for all, you have a single-payer system in Italy. It doesn’t work there…That would not solve the problem at all.”

During the March 15 Democratic presidential debate between Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, moderator Jake Tapper of CNN asked how to avoid a situation like that in Italy, where in some areas doctors are forced to decide who gets urgent treatment and who does not to survive the coronavirus. When it was Biden’s turn to answer, he said “With all due respect for Medicare for all, you have a single-payer system in Italy. It doesn’t work there…That would not solve the problem at all.”

Biden then promptly called for guaranteeing treatment for everyone irrespective of cost, precisely the premise of a single-payer system: “We can take care of that right now by making sure that no one has to pay for treatment, period, because of the crisis. No one has to pay for whatever drugs are needed, period, because of the crisis.”

So, in “normal” times Biden doesn’t think it’s necessary to provide a guarantee of universal coverage. In an emergency, however, “We just pass a law saying that you do not have to pay for any of this, period.”

Apparently, health problems for people who don’t have insurance aren’t an emergency until they threaten others.

Sanders missed the opportunity to call Biden on this glaring contradiction, and also failed to directly answer the charge that a single-payer system like Italy’s is failing the test posed by the crisis. He focused instead on the U.S. system’s failure to provide healthcare to all people, stressing that the current crisis “is only making a bad situation worse.”

Biden suggested that the situation in Italy proves that a public system doesn’t work. Sanders, on the other hand, said he wanted to eliminate private insurance completely, on principle. Neither of these ideological positions reflects how the health system actually functions in Italy. While Sanders’ call for a public guarantee of care reflects a fundamental goal to be pursued, it is essential to also identify the short-term financial mentality that has pervaded healthcare in both public and private systems in recent decades.

Senators Joe Biden, at left, and Bernie Sanders during March 15, 2020 debate. (Screenshot)

Systems in Italy & US

So how does healthcare function in Italy? And how does it compare to that of the United States?

Italy provides a universal guarantee of coverage — as do most European countries — in the context of a mixed public-private system. According to the OECD, the ratio between government and private spending on healthcare in Italy is 77 percent/23 percent.

Most European countries are in the same range, i.e. the system is not entirely public; many private providers exist, which allow patients to pay for services through both the public system or privately. So Sanders’ idea of eliminating private insurance altogether would not reflect the social democratic systems in Europe; even in Denmark, often taken as an example, private spending is close to 20 percent.

What about the United States? According to the same OECD statistics, government expenditures on healthcare are about 47 percent of the total. So public spending has a smaller, but still considerable role. If you’re covered by Medicare, Medicaid, or the Veterans Health Administration, you’re essentially using a single-payer system, but one that covers 30 percent less of the population’s needs than the one in Italy. You also have some out-of-pocket expenses for visits and drugs, but you are guaranteed a government-defined level of treatment.

In the United States, many seniors take out Medigap supplemental policies or Medicare Advantage plans, because the public system still leaves people facing costs for visits and treatments that can quickly become exorbitant, for drugs in particular.

In Italy, on the other hand, prescribed drugs cost very little, generally the equivalent of only about $2 per prescription. If you want a brand name drug, rather than the generic, you pay a little more, but still only about $5.

Doctor visits are different. In Italy’s public system, costs for visits or diagnostic exams have a co-pay that ranges from $30 to $60, similar to the cost in the U.S. with insurance.

The most visible drawback of the public system, however, is represented by waiting times for appointments. If you are not deemed an urgent case, you can wait months in some areas. Your primary care physician can override that by requiring a visit within three days, or by assigning a medium level of priority. But many people prefer to take out a private insurance policy that allows for visits within one-to-two weeks, and covers co-payments; these plans are often negotiated by labor unions or trade associations and offered for large categories of workers throughout the country.

Another difference is the ownership of healthcare facilities. In the United States only about 18.5 percent of hospitals are publicly owned, while 56.5 percent are non-profits, and the remaining 25 percent for-profit facilities (2018 data). In Italy, a slight majority of hospitals are publicly-owned (52 percent percent); significant, but less than what one might expect in a single-payer system. Almost half of the facilities are private, but the majority of services they provide are generally paid for through the public system.

Measuring Outcomes

The big question is how these differences affect outcomes. Neither system is purely public, nor is either one purely private. But which is better at caring for the population?

The World Health Organization ranks Italy’s health system No. 2 in the world; the United States is 37. Ranking systems is a complex process, as it’s not easy to distinguish between the performance of treatment, and other elements that affect the health of the population. Italy has one of the highest life expectancies in the world (82.7), while the United States is again far behind (77.8). However, these figures certainly reflect other factors such as diet, poverty, and gun violence; all points on which Italy has an advantage. Measuring the overall health of the population and how the health system deals with pathologies are two different things.

Medicare for All Rally, Los Angeles, February 2017. (Molly Adams, Flickr)

In terms of treating specific diseases, the United States can at least come close to the oft-repeated claim of having “the best healthcare in the world.” OECD statistics place the U.S. first for patient survival of breast cancer, fourth for ischemic strokes, fifth for colorectal cancer and seventh for heart attacks. Italy is behind on all of these measures, although it still ranks among the most advanced countries in the world.

Despite these figures, many Italians with whom I have spoken find it hard to recognize the strong points of the U.S. system, because they think it’s crazy for the United States not to guarantee “free” (in other words, taxpayer-supported) healthcare to everyone. This brings us to the obvious problems in the United States: cost, and inequality.

As people who are familiar with both systems know, if you have good insurance in the U.S., you can get excellent care: cutting-edge treatment, short waits, and the same doctor over time (often not possible in public systems). But there are tens of millions of people without health insurance. By some estimates, as much as 45 percent of working age adults were either uninsured or underinsured in 2018.

Americans put off medical care because it costs too much: on average 21.5 medical treatments, tests, or follow-ups per 100 patients due to costs, compared to only 3.2 in Italy. Thus people get sicker, have multiple conditions, and treatment is ultimately too little, too late. Not only does this make life measurably worse for tens of millions of Americans in normal times, but when it comes to an epidemic — as Sanders rightly pointed out during the last debate — it means that everyone is at greater risk. Faced with the COVID-19 pandemic, the weaknesses of the U.S. system may be magnified.

Importance of a Public Guarantee

In Italy, despite divisions among politicians over how much to incentivize private facilities, both left and right are clear that the strength of the country’s system lies in its universality. Giulio Gallera is the regional health councilor for Lombardy, currently the hardest-hit area in the world. On March 20, Gallera, who represents the center-right Forza Italia party, told Consortium News that despite the difficulties, “the Italian system is holding up, thanks to its universal nature.” It would be a huge risk, in his view, “to treat only some, and not others.”

Image on the outside of the main hospital in Bergamo, paying homage to Italy’s healthcare workers. (Andrew Spannaus)

Carlo Borghetti, a health expert in the center-left Democratic Party, is the vice president of the Lombardy Regional Parliament. He also said the system is doing well considering the circumstances, while stressing the importance of local monitoring to identify new infections rapidly and thus avoid the spread of the virus. “Thank goodness there’s a public system here,” he added, “I don’t know how things would go in a country without one.”

Yet it’s hard not to question Italy’s preparedness for this crisis. The system in Lombardy has been overwhelmed by the high number of COVID-19 cases, highlighting a lack of sufficient intensive-care units, respirators, and personal protection devices such as masks, which the country doesn’t produce.

In addition, Italy is having difficulty moving towards widespread testing, which is needed to implement the type of local monitoring mentioned by Borghetti. The problem is not a lack of swabs to take samples, but principally the small number of laboratories that can process them, only three in all of Lombardy, a region with 10 million inhabitants.

Efforts are underway to increase capacity, and the Italian company DiaSorin S.p.A. has just developed a new testing method, which allows for reducing the response time from four hours to 20 minutes. Italians proudly note that even the U.S. Food and Drug Administration is relying on DiaSorin, including by providing financing for the development of the new technology.

A statistic that stands out is the low number of hospital beds in Italy: 3.2 per 1,000 people, compared to 8 in Germany, and over 12 in South Korea. Yet the United States does even worse, at 2.8. In terms of acute care beds, however — a key factor in today’s crisis — the United States appears to be far ahead, despite discrepancies in statistics from different sources.

Borghetti says that hospital beds are no longer the way to measure healthcare; investment in drugs and technology is becoming the priority; and Italy is rapidly increasing capacity to face the crisis, going from 5,400 intensive-care beds to over 8,000 in recent weeks, according to Angelo Borrelli, the national commissioner for the coronavirus emergency. And another Italian company, from the city of Modena, has now developed a respirator that can treat two patients at once.

Effects of Austerity

Yet it’s undeniable that austerity policies, driven by the demand to cut public budgets to placate investors on the financial markets, have had a harsh effect on Italy’s public system.

Massimo Garavaglia was the budget councilor for the Lombardy Region from 2013 to 2018, and subsequently the deputy finance minister in the short-lived “populist” government formed by the League and the Five Star Movement in 2018. On March 20, he sent Consortium News a series of statistics from the Ministry of Finance on how much money was cut by the national government during the 2010s, which has reduced spending for health needs by 8 percent in less than 10 years, from 6.86 percent to 6.32 percent of GDP (see chart).

Reduction in spending on health needs in Italy as a percentage of GDP. Source: Italian Ministry of Finance statistics.

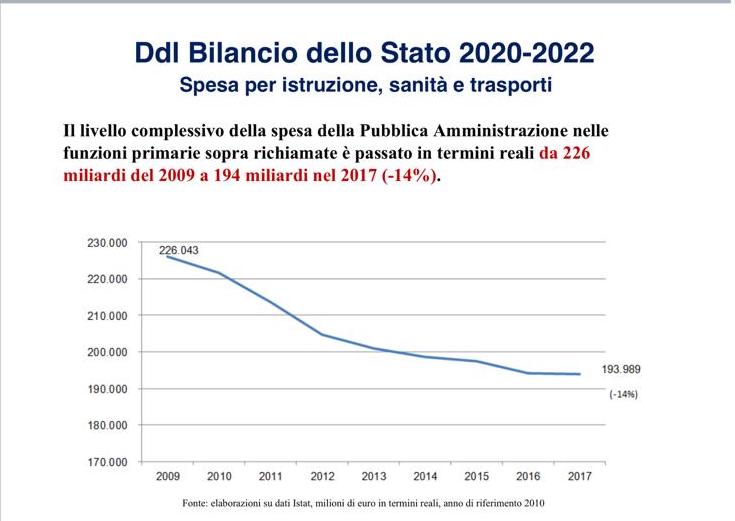

Overall spending on education, health, and transportation was cut by 14 percent from 2009 to 2017. So there’s no question that budget policies have made things worse, feeding the argument made by some on the right that government-run healthcare always ends up cutting costs and, as a result, the quality of care.

Reduction in spending on education, health, and transport. Source: Italian Ministry of Finance statistics.

Yet this outcome is at least partially due to a conscious attempt to gradually privatize Italian healthcare. Market mechanisms introduced in 1990s coincided with the overall wave of deregulation and liberalization measures implemented to pursue the policies of globalization demanded by the European Union in accordance with the desires of Western financial elites.

Despite claims from the free-market supporters, research also shows that the process of privatization did not improve outcomes at all: “Greater spending on public delivery of health services corresponded to faster reductions in avoidable mortality rates.”

Fabio Dragoni, the manager of a private health facility in Empoli (Tuscany) and an economic analyst for the newspaper La Verità, put it bluntly in a phone interview with Consortium News on March 21: “It’s math. Austerity has imposed a reduction of the number of services covered by the national system. As a consequence, the citizen either pays out-of-pocket or with private insurance, or doesn’t get care.”

Financial Mentality vs. Wellbeing

The United States is essentially in the same boat. First of all, almost half of health spending is public, as we have seen above; it’s not a “private” system, but a mixed one in which the poor, the elderly, and veterans have a public guarantee through Medicaid, Medicare, and the VA, while the rest of the population is split between those who are well-off and get excellent care, and tens of millions who have to choose between their health and financial ruin when they get sick.

The U.S. public side is also continuously subject to the same type of budget considerations as in Europe, from both Democratic and Republican administrations. President Barack Obama repeatedly presented the Affordable Care Act as a way to reduce the deficit, while the Trump White House’s recent budget proposal goes in the opposite direction of the promise “not to touch” health spending.

The dramatic expansion of a profit-seeking, financial approach to healthcare, triggered by the development of HMOs in the 1970s, has proved negative for overall care: according to a 2008 study published by the National Institute of Health: “The poor performance of U.S. health care is directly attributable to reliance on market mechanisms and for-profit firms, and should warn other nations from this path.”

So, the threat to healthcare from a bookkeeper’s mentality comes from both directions: on the one hand austerity, which places monetarist parameters over wellbeing, and on the other, the search for sources of financial profit, which leaves out those who can’t pay.

As for choosing which type of system is better, it would be best to leave behind an ideological approach. Few countries have a purely public or private system. Most have a mix between the two, and it makes sense to maintain the practices in both which lead to the highest level of care.

The challenge is how to provide that to everyone, avoiding any form of de facto rationing, whether through government decisions or the mechanisms of the market.

The lack of preparedness for the current crisis highlights the contradiction in Biden’s approach: the idea that we don’t need a government system, but in an emergency, we should provide a public guarantee of free healthcare for everyone.

If it is the role of government to ensure the health of all its citizens, then it should be unacceptable to leave anyone behind, even in periods when it’s easier to ignore their plight. A pandemic like COVID-19 merely exacerbates the problem, demonstrating that the financial mentality that has become pervasive in both public and private healthcare systems, has left us unprepared to deal with the threats we must face today.

Andrew Spannaus is a journalist and political analyst based in Milan, Italy. He is the founder of Transatlantico.info, which provides news and analysis to Italian institutions and businesses. His latest book is “Original Sins. Globalization, Populism, and the Six Contradictions Facing the European Union,” published in May 2019.

If you value this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will not be published. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments, which should not be longer than 300 words.

In a situation where it’s not really possible to compare like with like, it might be useful to point out that Spain and Italy, the two countries with the highest numbers of victims and deaths in the West, do have three factors in common that could account for the alarming speed with which coronavirus spead in the early stages. Both countries figure very high in the longevity table with 83,4 years average life expectancy. In both countries patients are prone to believing antibiotics are a cure-all for many common ailments, leading to a much lower resistance to illnesses that usually cure themselves given time. In both countries greetings are always acommpanied by hugs and kisses. Though these views may seem naive to many, my observations come from living in Spain for almost twenty years.

Where is this wonderful private insurance (U.S.) that this article seems to think exists? I found private insurance abysmal when I had it; it didn’t even cover interpretation of an MRI, which my Medicare did. Everyone I have known who finally was old enough to get Medicare loved it — the only idiot who didn’t was my Republican aunt who is so stupid she bought private Medicare then had to pay even more for a supplemental plan. Every time I went to my local rural health clinic and said my private insurance (through my husband’s workplace, a hospital) was terrible, the office workers told me everyone else said the same thing.

I found the details about the Italian system interesting, but I do agree with Bernie Sanders — NO PRIVATE INSURANCE. Fortunately for Americans, doctors who have a bit of sense can prescribe natural desiccated thyroid, whereas in the U.K. if you want genuine thyroid medication you MUST go to a private physician to get it.

Additionally, regarding breast cancer survival statistics, if you survive five years and one day, you are declared a survivor. Better would be to topple the breast cancer industry and deal with Americans’ iodine deficiency, a deficiency which leads to reproductive system cancers, elevated blood sugar, and other problems.

I agree Susan. The private insurance “option” is the camel’s nose under the tent. Without it the rich people will demand real quality performance from the public system. With a private option the rich will do everything they can to underfund and undermine the public system.

Of course, health depends not only on medicaments and medical care, but mainly as well on food, housing, general welfare, exercise, and all-round meeting of social needs. The US lack of sick leave, paid holidays, a livable minimum wage, security of work all make the likelihood of people who are not rich or in well-paid jobs with these benefits being unable to stay at home when sick. In other “democracies” like Italy these conditions help the citizens cope better. Another point about Lombardy is the extremely bad air pollution- the worst in Europe, which in a respiratory disease like COVID-19 is of course very pertinent.

We may notice very soon the difference in impact in the USA, which considers it can learn nothing from anyone else and needs no help even if offered, and the other stricken countries like Italy, Iran, South Korea, which cooperate fully with the WHO and with China, Russia, Cuba and other “evil nations” to help solve a global disaster.

1) Joe “hey, where you going with those feet in your mouth” Biden is a Class 5A “stronzo.”

2) I’m overjoyed the discussion turned to “economic austerity.” If not originated by the dynamic duo,

then, at least, it was aggressively pushed, globally, by the administration of Obumma and his VP “stronzo.” See, #1, above.

3) Re statement in the cited Gateston Institute article: “Government-run healthcare always ends up being about the government trying to cut its costs rather than to help its citizens.”

“Economic austerity” was imposed on Italy and the rest of Europe to benefit the investor class … and its negative effects on public benefits to the remaining 99% of the population goes well beyond “government-run healthcare.”

It’s is NOT an issue of healthcare, per se, but rather of government being purchased by the terminally avaricious and operated by their spineless lackeys. E.g., see #1, above.

Thank you, Andrew, for this excellent analysis of the distinction between the US and Italian health systems, and for exposing the careless and flippant “gotcha” response of Biden to Bernie’s Medicare for all proposal. I recommend to you and to CN the powerful speech of NY Gov Andrew Cuomo today as he inaugurated the makeshift hospital now being set up in the Javitts Center in NYC, which has become the epicenter of the pandemic in the US.

I’ve been saying for some time that the government no longer solves problems, it applies ideologies. Italy is having a problem precisely because they have done such a good job in the past – they have the oldest population in Europe – precisely the population most at risk from Corona virus.

“The challenge is how to provide that to everyone, avoiding any form of de facto rationing, whether through government decisions or the mechanisms of the market.”

Some rationing is necessary to keep in check, to some extend, rent seeking behavior of suppliers of drugs etc. A single payer system has a limited pool of money — decided by legislature — and it should plan to maximize health benefits. A drastic example is in EpiPen scandal. People who had severe allergic episodes benefit from carrying an injectable form of adrenalin = epinephrin, and replace it every six months or so. The cost of adrenalin is 1-2 dollars. The cheapest form is a solution in a glass ampule and a multi-purpose syringe that can last forever and costs about that much (unlike adrenalin that has to be replaced whether used or not), but a “normal person in anaphylactic shock” may have trouble using it. In Poland, insurance covers a more expensive form, a syringe pre-filled with the measured amount of adrenalin, you just remove the wrapping, stab your thigh and press the piston. The price is 16-20 dollars. But you can have a more expensive EpiPen for 75 dollars, you unwrap, stab and you do not have to press the piston. In USA the cheaper forms were somehow regulated out of the circulation and the producer increased the price of EpiPen from 150 to 300 dollars.

Interestingly, a legislature was passed requiring all emergency providers to have EpiPens. A school nurse or an emergency worker should have no problem with the cheapest form so this is very, very stupid. And a healthy person without arthritis should not have a problem with the middle price form. Lack of availability is very, very stupid. Mind you, the utility is in carrying it “just in case”, when you are exposed to a bee bite, pesticide that you do not tolerate etc. And when the cheap forms are available and serve most of uses, the most expensive form is four times cheaper.

Maybe the US should take some of the trillions of dollars it spends destroying other people’s countries, and spend it on healthcare, instead?

And maybe get rid of for-profit healthcare and insurance altogether? Because as long as someone is deprived of reasonable service, every dollar of profit is a travesty.

Throughout the world, we need guaranteed universal healthcare coverage for all citizens and not only in times of crisis but at all times, period! Joe Biden is playing double standards here by saying that you only need it in emergencies!

excellent article. I hope to see more from this guy. I´ll buy his book

Outstanding article.

I am a US expat living in Austria (Vienna) and must say that the medical system here is excellent.

Like Italy, Austria has a mixed public-private system which, in distinction to the USA doesn’t provide socialism for the elderly, military and poor and the “market” for everyone else – a market in which employees of large organizations and the wealthy do well, and others fall through the cracks.

Instead there is basic, good coverage guaranteed for all, with additional services available privately. Persons are insured through one of various non-profit insurance groups organized by line of work (employees/umemployed), self-employed, public sector, railroad, etc. Most doctors, general practitioners as well as specialists, and all public hospitals (not including some private clinics) are financed through these insurance groups.

The quality of care, in my experience, is excellent; there is full choice of doctors and hospitals There are also private doctors (often well-known professors and specialists), private clinics and additional private services (such as a deluxe hospital room) that can be paid for additionally, out-of-pocket, and which are generally financed through private, “additional” health and accident insurance.

Private insurance companies play a strong role in insuring such additional services and covering the minor gaps and co-pays under the state system.

All in all, the medical services in Austria are outstanding, there are no issues of waiting or rationing (as apparently there is in the UK), and the system is democratic, providing a high-level of care to all residents.

The USA can learn a lot from this system, as well as from other European systems. Simply saying “we’re the best in the world” in this area when this is patent BS doesn’t cut it. The mix of a so-called market approach for the broad masses, combined with socialism for the old, military and poor, has resulted in a highly distorted and inequitable pricing system, where those “falling through the cracks” pay extortionate, totally arbitrary prices set by some billing software (or alternatively are bankrupted), and even those who haven’t (yet) fallen through the cracks have super-high deductibles and co-pays provided by Obamacare and other “fixes”, which have only succeed in making a failed system even worse. This combined with enormous malpractice insurance premia saddling doctors, as a result of a skewed legal system. And all of this held in place by the lobbying of politicians carried out by insurance companies, professional associations, trial lawyers and others who benefit mightily from the current system.

There needs to be a revolutionary change in the US system of financing medical services (as well as higher education services) and sadly Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden are not the persons who can or will carry this out.

An aside to my above comment: The billing software systems used by hospitals in the USA are called “chargemasters”, essentially price lists for countless services and materials provided, kept secret from the patients (customers) until the time of billing, with prices that are grotesquely inflated. See: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chargemaster These are not price lists in the usual sense of the term, which one would expect from an auto repair shop or other reputable business, but unrealistic inflated demands for use in negotiations with either insurance companies (in which case the patient isn’t directly involved) or with uninsured patients, in which case the patient is gouged. This is an enormous scandal which I believe only one state – California – has really tried to deal with through legislation. And this is one factor making the medical services market in the USA totally intransparent, as the customers (patients) have no clue what they will be charged, get no “estimates” in advance (unlike at the auto mechanic), and are compelled to use the services by reason of their illness, accident or condition.

This hits the nail squarely on the head. Thank you to Andrew Spannaus for showing the nakedness and emptiness of Plagiarist Joe.

This Swiss site which examines media and propaganda is posting some very interesting material regarding all of this. The English translation of Italy’s own health ministry’s report on the actual demographic breakdown of deaths attributed to coronavirus is rather mind bending in its own right I dare say. Other more recent posts follow this first post regarding Italy as one scrolls down.

see: swprs.org/a-swiss-doctor-on-covid-19/