A new book attacking the French scholar for his views on Israel and Zionism spurs As`ad AbuKhalil to provide his own assessment.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

The French Orientalist Maxime Rodinson was by far one of the greatest scholars on Islam and the Arab world in the 20thcentury (if not ever). His contributions belie the notion that all Orientalist production can be dismissed as purely ideological (and that was not the contention of Edward Said in his “Orientalism,” all distortions of Said’s work notwithstanding). I, for one, owe a great debt of gratitude to Rodinson for influencing me early on in my conception of, and education in, Middle East studies. Rodinson wrote the best contemporary biography of the Prophet, and he examined him from a Marxist historical perspective (the book was translated into many languages, including Persian but not Arabic).

The French Orientalist Maxime Rodinson was by far one of the greatest scholars on Islam and the Arab world in the 20thcentury (if not ever). His contributions belie the notion that all Orientalist production can be dismissed as purely ideological (and that was not the contention of Edward Said in his “Orientalism,” all distortions of Said’s work notwithstanding). I, for one, owe a great debt of gratitude to Rodinson for influencing me early on in my conception of, and education in, Middle East studies. Rodinson wrote the best contemporary biography of the Prophet, and he examined him from a Marxist historical perspective (the book was translated into many languages, including Persian but not Arabic).

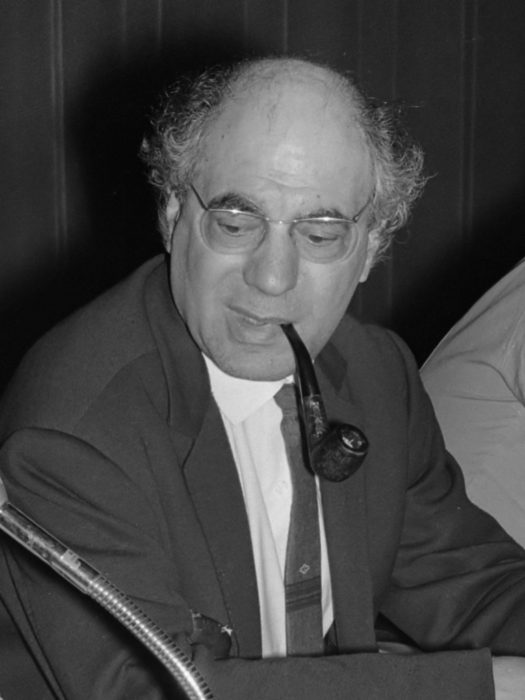

Maxime Rodinson in 1970. (Rob Mieremet, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons)

Rodinson’s “Islam and Capitalism” also powerfully debunked classical Orientalist myths about Islam and Muslims (including the thesis of Max Weber about capitalism and Protestantism) by showing that Muslims were able to go around the theoretical theological ban on usury in their financial transactions. Later, in “Europe and the Mystique of Islam,” Rodinson introduced the notion of “theologocentrism” to critically characterize the Western school of thought in academia that attributes all observable phenomena among Muslims to matters of theology. Furthermore, refreshingly, Rodinson paid attention to Arab leftism and wrote about Lebanese and Syrian communists who he knew well in the seven years he spent between Syria and Lebanon during and after World War II.

Attention to Rodinson is prompted by the publication of Susie Linfield’s “The Lions’ Den: Zionism and the Left from Hannah Arendt to Noam Chomsky.” The author is a professor of journalism at NYU and has no background in Middle East studies. Yet, she uses her platform to launch an attack on critics of Israel and Zionism and situate them in the category of self-hating Jews. But her method of handling Rodinson is not even honest: she accuses the author (who lost his parents in Auschwitz) of not talking about his Jewish background or even about Nazi atrocities when, in fact, he spoke at length about such matters. She even accuses Rodinson of being silent about the crimes of Arab governments and misdeeds of the PLO when he was a harsh critic of them both. And she makes up a story that Rodinson was accused by Arabs of “lacking respect for Islam (and worse)” without providing any evidence. Rodinson remains highly respected in the Arab world.

Rodinson was born to Jewish communist parents (his father played chess with Leon Trotsky), who were fierce anti-Zionists. He grew up in a secular atheist family, and that rankled Linfield, who considered it a disqualifier in his writings on Palestine. Not identifying with an ancestral religion is anyone’s right, including Rodinson who became a communist early in his youth. He also developed a keen interest in languages and Middle East studies. Rodinson never tried to ignore the Palestinian question: in the West, talking about the Palestinian question from a non-Zionist, or anti-Zionist, perspective can result in enormous pressures and negative consequences. To this very day, many Western academics choose to either champion Zionism or to ignore the Arab-Israeli conflict altogether (many of the Western academics who feigned concern for the Syrian people in recent years had never written or said a word about Palestinians).

‘Most Famous Anti-Zionist in France’

Rodinson became (in his own words) “the most famous anti-Zionist in France” (“Cult, Ghetto, and State,” p. 23). His piece for Jean-Paul Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes in 1967 made Rodinson a target of Zionist forces worldwide. His article (later published as a book, including in Arabic) was titled “Israel: A Colonial-Settler State?” While Rodinson answered his question in a sophisticated argument in the affirmative, he qualified the answer with an attempt to provide Israeli founding with extenuating circumstances. In other words, Rodinson’s stance on the Palestinian question was not as radical as it was reputed to be although his arguments about the nature of the Zionist project were quite radical — and accurate.

Linfield finds Rodinson’s characterization of anti-Semitism among Arabs to be apologetic, while he was clearly critical of the plight of non-Muslims under Muslim rule historically. But Rodinson lived among the Arabs, and was accepted by them, in the 1940s, when Jews (regardless whether they were practicing or not) were being exterminated in Europe. Rodinson knows more about Arab attitudes toward Jews than Linfield. Rodinson rightly pointed out that the creation of Israel triggered the rise of anti-Semitism among Arabs and resulted in the translation of some Western works of anti-Semitism (even Bernard Lewis concedes that Arab anti-Semitism is political).

In May 1972, Rodinson gave an interview to Shu`un Filastiniyyah in which he gave an accounting of his views of the conflict (it was reprinted in “Cult, Ghetto, and State”). In that interview, Rodinson (commenting on a remark by the late professor Ismail Faruqi to the effect that a Zionist state is objectionable even if it was established on the moon) said that he would not object to a Jewish state on the moon. But should not a secular Marxist object to any state with a religious identify and which is founded on the principle of the juridical supremacy of one religious group over others? Rodinson’s point was to remind readers that his objection to the Jewish state was not in principle but was due to the displacement of the native Palestinian population and the harm that Israel has inflicted on them.

Israel’s Founding

Having said that, Rodinson in his book, “Israel: A Colonial-Settler State,” does not shy away from answering in the affirmative. The extenuating circumstances that he provides to the Zionist argument are that: No. 1) the immigration of Jews from Europe due to Nazi crimes was a matter of survival; No. 2) the socialist character of the Yishuv; No. 3) he talks about the sale of land to the Jews and says that it was “to the benefit of the seller and the agricultural development of the country” (p. 87).

But the immigration of Jews into Palestine took place without the consent of the native population, and it was forced either by the British government or by illegal immigration of Jews: and Western governments that were generous with their support for Jewish immigration into Palestine were strict about their restriction on Jewish immigration into their lands.

Furthermore, the question of land sale is not really salient to the discussion of the creation of Israel because Israel became a Jewish state by force and not by legal transactions (the percentage of land sold to the Jews was minuscule in comparison to the forced theft of Palestinian land).

Finally, the socialist character of the Yishuv should be irrelevant to a discussion of a colonial subjugation of a people: what does it matter to the victims if their oppressors and killers were socialist or capitalists? (This while the socialist character of the Yishuv has been highly exaggerated and the experiment ended in an ultra-capitalist state, and Western socialists have never been free of racism and prejudice). Zionists began to abuse the natives and practice discrimination against them from early on. (The ideal of “Hebrew labor” referred to the deliberate exclusion of Arab workers from Jewish enterprises).

Rodinson agrees that Zionist settlement amounted to colonialism but then proceeds to suggest that Israel was a peculiar kind of colonialism because the occupiers wanted to rule over a territory but not a population. But how can you rule over a territory and not rule over a population, most of whom were expelled by force in 1948? And does that argument make a difference to the victims? To rule over a territory and not bother with the population is the worst kind of colonialism.

Rodinson makes a strong case against Israel but then provides weak solutions that are not commensurate with the crimes that he helped expose. While he says that Arabs should determine the outcome of the struggle themselves, he advises against military solutions. How did history treat those who called on the French living under Nazi occupation (or blacks under Apartheid South Africa) to practice pacifism?

Rodinson maintains that there are two distinct communities in Palestine that have to be represented in two separate political entities, i.e. two-state (non-solution). It is ironic that Rodinson’s powerful refutation of Zionist claims concludes with a weak call for Palestinian accommodation of Zionist occupation over 78 percent of historic Palestine. But Rodinson also said (in “Israel and the Arabs”): “On the other hand, a total victory for the Arabs some day is not out of the question. Israel’s military superiority will not last forever, or, at least, will not be absolute forever” (p. 352). If only Rodinson had been around to watch the Israeli humiliation in South Lebanon in 2006.

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism” (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

If you enjoyed this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

The days of wine, roses, and Golda laugh and run away like a child at play

Through a meadow land toward a closing door

A door marked “nevermore” that wasn’t there before

ditto, for Mancini’s Exodus….

It all gotten rather annoying, and nonsensical..

Lewis was an old school raconteur who liked his own stories a little too much for his own good (based on some extremely recondite textual detail that few can challenge him on). Modern scholarship challenges these simplistic tales of “takeoff” in one society and “stagnation” in another. The case this book makes is that there wasn’t a great difference in productivity of putative slaves in the non-West and brutally used and abused laborers in the West until 1875 or so, when the 2nd Industrial Revolution kicked in.

https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/after-oriental-despotism-9781472533395/

Funny how there is no way to actually unsubscribe from this rag, one is reduced to constantly hitting the spam button.

Thanks for this excellent article. A worthy companion article by Tom Suarez, based on his great book, is

“Terrorism: How the Israeli state was won”

http://mondoweiss.net/2017/01/terrorism-israeli-state

Very, very well-articulated, Professor of Political Science, AbuKhalil

This response comment is by a lay person who feels he would have benefited greatly from your erudition, on the subject being discussed, had he been a student of yours.

Being a Professor of journalism, on the other hand, may mean one has the mastery of language, as well as the skill to commit to paper that which one opines, but it certainly is not divinely accurate, or even a correct and truthful interpretation of historical detail.

Professor or not, in this instance, Susie Linfield’s analysis is this one individual’s opinion on the subject – as valid, or not, as any other lay observer. As we all know, for anything to be valid, it must be entirely fact based, at least when it deals with the history of humanity.

History, like journalism and the bible (Old Testament or New, the Koran or any other institutional documentary) is written by the fallible hand of man. And as we know, the human mind, over time, has been inculcated with biases; never mind the admonitions not to be so inclined.

Written history ought not be mere storytelling, as is the bible, yet both bible fables, as well as journalistic ‘news’ stories, are based on ideologies of narrow, apparently irremediably self-righteousness creations of what are termed: in-group and out-group assumptions.

I could understand you better, if you actually challenged directly some of the professor’s specific points.

Trump’s accusation of Ilhan Omar’s “anti Israel bias” is illustrative of the colonialist and imperialist Self Ordained superiority and bellicose “exceptionalism” that disallows a True ‘freedom of thought and speech’ and, instead, herds “Loyal Citizens” (Trump Supporters) into obeisance / submission / acquiescence.

https://www.newstatesman.com/world/north-america/2019/07/donald-trumps-attacks-ilhan-omar-show-fascism-coming-us

/////////////////

An authentic, insightful book concerning the refugee experience can be found in “The Ungrateful Refugee” – by Dina Nayeri

[short video here ] — http://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2019/07/18/amanpour-dina-nayeri-the-ungreatful-refugee.cnn

oops! ! — Please accept my HUMBLE apology for all of my overbearing, clumsy mistakes on this page. …

http://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2019/07/18/amenpour-dina-nayeri-the-ungreatful-refugee.cnn

That Linfield — who mischaracterized the author she’s criticizing and committed several (likely willful) omissions regarding his works — is a professor of journalism speaks volumes about not just the quality, not also the underlying ethics, of journalism as taught in the US. Sort of like Alan Dershowitz being a law professor.

Israel’s founders and early leaders were, of course, “socialist” for their kin only. Pretty similar to today’s neoliberalism, really. The only difference was that Ben Gurion’s “socialism” was “socialism for my people, and you Palestinians can drop dead,” while the neoliberal version is more like “socialism for us, and you peasants and the environment can drop dead after you mine our metals, construct our mansions, and buy our products.”

Wanting the territory and not the population — all of Palestine and zero Palestinian — is, perhaps, one of the many factors that has made Israeli Zionists identify so well with Americans: that’s how the latter handled the natives of the land they stole. While they brought over Africans to be enslaved, their view on Native Americans was premised on extermination: if not outright killing the natives, then the “Indian in them.”

Thankyou for the comparison with our, USA, history; one which I have been describing for years. A description, however, that most people are mysteriously unable to grasp. Again, thanks.

Thank you, very interesting. And yes, colonizers of North America had wanted land without people, nothing new here.

Trump’s accusation of Ilhan Omar’s “anti Israel bias” is illustrative of the colonialist and imperialist Self Ordained superiority and bellicose “exceptionalism” that disallows a True ‘freedom of thought and speech’ and, instead, herds “Loyal Citizens” (Trump Supporters) into obeisance / submission / acquiescence.

https://www.newstatesman.com/world/north-america/2019/07/donald-trumps-attacks-ilhan-omar-show-fascism-coming-us

/////////////////

An authentic, insightful book concerning the refugee experience can be found in “The Ungrateful Refugee” – by Dina Nayeri

[short video here ] — http://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2019/07/18/amanpour-dina-nayeri-the-ungreatful-refugee.cnn

Trump’s accusation of Ilhan Omar’s “anti Israel bias” is illustrative of the colonialist and imperialist Self Ordained superiority and bellicose “exceptionalism” that disallows a True ‘freedom of thought and speech’ and, instead, herds “Loyal Citizens” (Trump Supporters) into obeisance / submission / acquiescence.

https://www.newstatesman.com/world/north-america/2019/07/donald-trumps-attacks-ilhan-omar-show-fascism-coming-us

/////////////////

An authentic, insightful book concerning the refugee experience can be found in “The Ungrateful Refugee” – by Dina Nayeri

[short video here ] — http://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2019/07/18/amanpour-dina-nayeri-the-ungreatful-refugee.cnn

but notice that when the u.s. conquered half of mexico in 1848 the conquered mexicans were immediately given the option of voting u.s. citizenship. that is the paradigm israel should have followed and still should. it is the one state solution of, among others, president trump. it is the most practical, safe, peaceful, inexpensive, and likely to occur of any of the endgames proposed thus far.

Zionist apartheid colony should follow all other colonies to the dustbin of history.

but note that when the u.s. conquered half of mexico in 1848, as part of the peace treaty it gave the conquered mexicans the option of immediate, voting u.s. citizenship. that should have been the paradigm israel followed after 1967 and it still can be. this is the one state solution as proposed by president trump, among others. it is the safest, most practical, least expensive, most peaceful, least disruptive of all the endgames for israel/palestine proposed thus far.

Texas rangers also murdered Hispanic farmers and ranchers for their land.

https://www.elpasotimes.com/story/news/2018/01/26/100-years-later-porvenir-massacre-haunts-descendants-texas-border/1058345001

Watch the movie ‘Lone Star’ for what things were like until the 50s ( https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UffK-IHM1B0 ). Lyndon Johnson and John Kennedy would not have become national figures if it weren’t for a few South Texas counties:

https://www.texasmonthly.com/politics/go-ask-alice

This article has once again confused the difference in the workings (raison d’etre) of colonialism and imperialism, outlined succintly by J.A. Hobson’s Imperialism: A Study (1902), avidly read and understood as the seminal work on the subject by such readers as V.I. Lenin.

In a nutshell, regarding the native population:

Colonialism says, “This is our land now! Get the f**k out! We don’t want you here no more. And if you resist, we’ll kill every last one of you.”

Imperialism says, “Stay as long as you like. As long as you work in our mines and factories and on our plantations and pay your taxes (in our currency) on time. If not, Get the f**k out, there are plenty of your kind to choose from. You people come a dime a dozen.”

Lenin’s work on imperialism is even better, based of Hobson’s book too, among others.

Lenin, of course, was anti-Zionist.

Lenin was a narcissistic personality disorder/idealist fanatic personalized. Here’s a view of someone who met him personally:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6TK9c-caEcw

Trump’s accusation of Ilhan Omar’s “anti Israel bias” is illustrative of the colonialist and imperialist Self Ordained superiority and bellicose “exceptionalism” that disallows a True ‘freedom of thought and speech’ and, instead, herds “Loyal Citizens” (Trump Supporters) into obeisance / submission / acquiescence.

https://www.newstatesman.com/world/north-america/2019/07/donald-trumps-attacks-ilhan-omar-show-fascism-coming-us

/////////////////

An authentic, insightful book concerning the refugee experience can be found in “The Ungrateful Refugee” – by Dina Nayeri

[short video here ] — http://www.cnn.com/videos/world/2019/07/18/amanpour-dina-nayeri-the-ungreatful-refugee.cnn

The modern distinction is between “Settler Colonialism” and “Franchise Colonialism”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwj5bcLG8ic

http://www.kooriweb.org/foley/resources/pdfs/89.pdf

Lenin was a precursor to Trump in coming up the word salad needed for him to acquire power:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WsC0q3CO6lM

Sadly, there’s a fair probability that anyone who regards Lenin as a “seminal” thinker will sound like the fanatical Trotskyite questioner in last clip

The Jewish tight grips on the world’s capitals have facilitated America becoming the superpower since the end of WWII. But it is exactly these same capitals have led to the greed, corruption among American privileged elite class. As a result of this, the extreme income and wealth inequalities will soon or later cause a social unrest which threatens to lead to another American civil war, and the ensuing American’s decline, though economically not militarily. Will the rising anti-semitism in many America large cities force the Jews to emigrate to the European continent?

As a pipe-smoking pro-Palestinian, I say thank you.

No question, anti-Jewish racism is been quite fashionable among our bourgeoisie today.

DH,

Please expound, I cannot fathom where you are coming from..

Is being pro-Palestinian a problem for you?

Zionist apartheid is OK to DH Fabian, I see.

It is anti Zionism politics. Zionists hide behind jews..

DH is a “one note wonder” when it comes to singing the praises of Israel. Yet I have yet to see him make any coherent reply to any specific criticism. And of course the conflation of anti-semitism with anti-zionism is typical Hasbera.

We will never know whether or not JFK was one who was more than willing to have the discussion Bob Van Noy says we need to have now about the consequences of WWII. I believe he was more likely willing to have this conversation that any president before and definitely more willing than any after him.

Thee Dulles Brothers with the aid of Robert Blum hijacked the CIA by fostering it’s design in the image they themselves sought.

CIA apparently ran interference for Israel’s Zalmon Shapiro and his NUMEC corp. I’m all for it BOB Van Noy. Maybe the need for this conversation will convince a compromised DOJ to release all the JFK and NUMEC files.

Let us remember that the court ruled against Jefferson Morely in his suit to get the files because he didn’t prove that the public would benefit from the release of these records.

I wonder what the public would think of having an extra 10 billion dollars + to spend on medical care or education. Never mind the trillions spent trying to restore order to the middle east because of the NEOCONC endless war philosophy.

Yes sir Bob we need to talk about these things that were kept “hush hush” for so long.

You cannot make this bull s#*& up. Let them steal SNM and then pay them because they are blackmailing the government who let them do it!

No credible explanation exists for what happened here. Anyone with half a brain would have realized the insanity of such an action.

We all have this albatross hung around our necks because of a few insane, greed propelled greed heads.

The progressive democrats need to tie the Queen of Chaos to table and water board her until she coughs up the true story of the DNC

email saga.

If the dimos started pouring water today it wouldn’t be soon enough. I mean if she died what would it matter, to paraphrase her highness.

Now where did I put the file to hone my pitchfork with.

robert e williamson jr,

I don’t know what article you are responding to — but it is obviously not this one!

The creation of the Zionist Apartheid State on the grounds of expediency, guilt, corruption, and influence peddling was a form of Original Sin that has haunted the world ever since and may yet destroy it. Just as slavery poisoned relations between the races in the US and reduced them to a level from which they will never recover.

Apartheid means that ethnic separation is the law and is enforced by the state.

In Israel ethnic separation is illegal and is actively combatted by the state. Therefore Israel is not an apartheid state.

Proof:

“Under pressure by the Nazareth District Court, the Attorney-General’s Office and the NGO Adalah, Afula will reopen its parks to non-residents, including Arabs within two days, it was announced on Sunday. The development comes after Adalah sued Afula for discrimination in blocking Arabs from entering its parks and after the Attorney-General’s Office supported the NGO’s lawsuit.”

Source:

Afula to open its parks to Arabs, non-residents in 2 days, court rules, by Yonah Jeremy Bob and Maayan Jaffe-Hoffman. Jerusalem Post, July 14, 2019

https://www.jpost.com/Israel-News/Afula-to-open-its-parks-to-Arabs-non-residents-in-2-days-595615

ALL Zionist apartheid IS by law – the apartheid law, of course. There is a list of apartheid laws

https://www.adalah.org/en/law/index?page=4

If Bob Van Noy is correct here and I believe he definitely is, the argument that the U.S. should have never been allowed to turn it’s head while Israel was stealing SNM, special nuclear materials, should be at beginning of the discussion. For it is the perfect example of someone taking liberties with the law.

Interesting article. Linfield’s book sounds horrible, so thanks for pointing that out. But a couple of points. Regarding the statement, “Rodinson’s ‘Islam and Capitalism’ also powerfully debunked classical Orientalist myths about Islam and Muslims (including the thesis of Max Weber about capitalism and Protestantism) by showing that Muslims were able to go around the theoretical theological ban on usury in their financial transactions” — the problem is that usury is not capitalist but pre-capitalist. Capitalism lowered interest rates so that money could be profitably invested. But that’s not the only thing wrong with “Islam and Capitalism.” It’s also curiously silent on the question of Muslim slavery, which was in fact ubiquitous. This is important because the overthrow of slavery in the west was crucial to the rise of capitalism (despite the fact that the practice was later reborn in capitalist outposts in the western hemisphere). It was one of the institutions holding the Islamic world back and preventing a leap to modernity. The Angry Arab might want to check out Bernard Lewis’s Race and Slavery in the Middle East: A Historical Inquiry (1990), which, believe it or not, is actually quite good. But any suggestion that Lewis is worth reading will probably make him angrier still.

“. .. the overthrow of slavery in the west was crucial to the rise of capitalism (despite the fact that the practice was later reborn in capitalist outposts in the western hemisphere).”

I’m glad to see the caveat, but the thesis itself is simply an assertion. In fact slavery in the west was crucial to the rise of capitalism- “its overthrow” and other rumours of its death, greatly exaggerated.

To change the subject, only marginally, the parallels between the occupations of Palestine and north america are one of the reasons why zionism gets so much public support in the US, Canada and elsewhere where the population has been displaced and dispossessed within living memory.

“.. the question of land sale is not really salient to the discussion of the creation of Israel because Israel became a Jewish state by force and not by legal transactions (the percentage of land sold to the Jews was minuscule in comparison to the forced theft of Palestinian land).”

Right on, bevin, regarding both remarks. To assert that “slavery” is (one of the things) that prevented the Muslim world from becoming “capitalist” (rather than mercantilist, I presume) is orientalist. And it is ahistorical to assert that western capitalism (which began nestled within mercantilism and is virtually indistinguishable from it) arose post the end of slavery!

If by “capitalism” Mr Lazare means *industrial* capitalism – that got underway in the mid-late 18th century (in the UK) and benefited mightily from both the destruction (intended) of Indian cotton manufacturing but more pertinently and largely from slavery in the USA, which didn’t end until 1865, by which time the “second industrial revolution” was well underway (initiated by the invention of the railway/roads – again in the UK). Yes the UK had itself made slave trading illegal in 1807, but it had little effect on the use of slaves for the production of cotton in the US (and sugarcane continued to be produced in the Caribbean, including on UK controlled islands, by slaves until 1834).

And yes, bevin, your argument re the parallels between Israel’s 70 + year ethnic-cleansing of the Palestinians, the rightful inhabitants and dwellers/owners of that land and what was done (and continues to be effected on) to Native Americans across the Americas, but most pointedly, given the relationship, in the USA holds water. Indeed, I believe it was Amos Oz who, in an interview, raised the parallel and its cause for amity between the USA and Israel.

I would only add to that: Australia and Canada and perhaps to a lesser extent New Zealand. The British (and that’s my origin) really did a number on so many people; we have been responsible for so much harm to so many people. Including Palestinians.

Jabotinsky the hero of Zionist European colonizers (his family name shows that his family was from some Slavic-language place – in Ukraine or such) 100 years ago in his “Iron Wall” had not only claimed that Zionism was colonialism (and compared Zionist to colonizers of the North America), he also admitted that natives always(!) resisted the colonizers.

“Jaba” means a frog in Ukrainian language.

Yes, Western capitalism also had been a reason for the 2nd edition of serfdom in Poland and Russia – almost slavery. It had been introduced to supply capitalist West with row materials and food.

And bevin might I add that *any* writer, person who quotes Bernard Lewis and his works in support of their opinions is as *Orientalist* (and thus racist) and as an ardent a Zionist as Lewis was.

And this Lazare does in his response to Professor AbuKhalil.

Thus, how can one trust their viewpoints on the Middle East and North Africa, their arguments, their purported facts?

Thank you As’ad AbuKhailil for the info and insight.

Let’s face it the problem in Israel would not be nearly as dire for the world if Israel had not acquired nuclear weapons capability. Some how everyone seems to forget that the Palestinians are not the only people threatened by the “Outlaw Israeli and U.S. Governments”.

All thanks to the Deep State via the CIA.

The fact that Israel was allowed to steal fissionable “special nuclear materials” (see the NUMEC story) and some in our government, CIA & DOJ aided in keeping the fact secret is for me unforgivable. I demand justice as should the DOJ. Those secrets and that material was not CIA’s to give away. Those secrets and that material was paid for by my both grandfather’s taxes and my fathers taxes and now I and all others are being taxed to help support the thieves.

The DOJ has been forever compromised.

No surprise to me that Americans do not vote. Why bother?

Our government has failed us in a most egregious manner, this theft was treasonous and Lady Justice is no where to be found.

WAKE UP AMERICA!

Thank you, Professor AbuKhalil. Clearly Mr Rodinson was not an Ilan Pappe (one can only imagine the apoplexy that Ms Linfield endured on reading Professor Pappe’s works, if she ever has done so).

Indeed, Mr Rodinson would seem to have been one in a long line of “socialist” apologists for the “creation and existence” of Israel. At its best, kindest, “Sorry for stealing your land, and throwing you out of your country and refusing you and your descendants the right of return, but you have to understand, recognize that we have always been so much more badly treated, and this historically as well as under the Nazis, than any other group in the world. Our holocaust was and is so much worse than any other genocide inflicted on any other group. We need a country of our own in order to be safe and yours is available to us by gift (from GB) and force of arms. We hope that you don’t mind, but we don’t want to have you as our neighbors, living on the same street, on our borders. There are more of you than us, so we can’t let you back in. Hope you have a nice time elsewhere.”

We are only now beginning the serious and wide discussion about the consequences of WWII and the decisions made before and after the fighting. This insight becomes part of the now essential discussion of the many sided geopolitical upheaval created by War. The simplifications that we’re so familiar with is just that, not nearly encompassing enough to evaluate. The insights that we’re now being presented are invaluable and unique to our contemporary experience. Thank you As’ad AbuKhalil and Consortiumnews…