The death of freelance journalist Arnaud Dubus symbolizes the demise of his beloved profession.

Our colleague and brother Arnaud Dubus is dead. On Monday, 29th of April, the former journalist, recently turned spokesperson for the French embassy in Bangkok, stepped out of his office, leaving his bag and phone behind.

He rode a motorbike-taxi to the nearest sky-train station. Then, after taking the escalator to the platforms, he jumped onto the street below. A few minutes later, he was dead.

We, his friends, a small community of French journalists in Bangkok, are devastated by his suicide. We lost a precious friend, a true fountain of knowledge on the culture and mysteries of Southeast Asia, and a sensitive and kind man. We are also shocked because his death is symptomatic of the struggles thousands of foreign correspondents are facing around the world.

Of course, nothing can ever fully explain Arnaud’s pain and the personal reasons that pushed him to make such a final decision. But we all know that his financial difficulties, especially in the past decade, affected him severely. Even as he contributed to major French media outlets including Liberation, Radio France Internationale and Le Temps for several decades, he could no longer make a decent living and was forced to change career last year.

Pitches Left Unanswered

Arnaud had to take this step despite being a reputable expert on the region: he produced many excellent pieces on the Khmer Rouge, army politics in Thailand and Burma, power games in Buddhism, and he had recently uncovered a major corruption scandal in Malaysia. Simply put, Arnaud Dubus was considered one of the best French language writers in South East Asia.

Yet the story pitches he sent to newspapers were often left unanswered. During annual visits to his employers’ offices in Paris, he felt that some editors barely acknowledged him – a middle-age exiled reporter, skinny, discreet and modest, writing about an exotic part of the world few media still care about.

The print media crisis, the routine use of agency content by newspapers had made his income dwindle, a little more every year, but he didn’t dare to complain. He was too humble, too isolated, too humiliated by the downgrading of his living conditions so late in life, to ever mention this to anybody outside his circle of close colleagues.

The Liberation newspaper cut off his digital subscription, with the excuse that “you don’t work enough for us”. Radio France Internationale, a state-owned broadcaster, recently decided to stop providing social security and pension benefits to their freelancers abroad.

Arnaud was struggling with depression and followed medical treatment for the past decade. As he could no longer afford medical care, he had to interrupt his treatment.

Apparently, he should have been content with his meagre freelance salary –between $700 and $1,600 a month, that is, in the good months. Let’s briefly talk numbers: international newspapers today pay less than $100 for a short 250-word article, around $700 for a longer piece that will require a week’s research, field work and writing. This rate has not increased in the past fifteen years.

If one has to pay one’s own expenses including hotels, transportation, translators (Arnaud spoke and read Thai, unlike most foreign journalists in the country), reporting is no longer financially viable. Like many of us, Arnaud could simply not afford to report anymore. We are called “foreign correspondents”, on paper or on air, but in reality, the majority of us are freelancers without a fixed salary, without healthcare, and without the resources needed to investigate.

Big Footed

With his soft and ironic smile, he would welcome the “special envoys” sent by his employers for big events, even though they were coming to take those jobs from him that should have allowed him to set a bit of money aside in anticipation of slower times of the year. To be a “foreign correspondent” today often means editors expect you to contribute new perspectives and crucial expertise in little known parts of the world, but they will send a staff journalist to represent the brand for important media coverage.

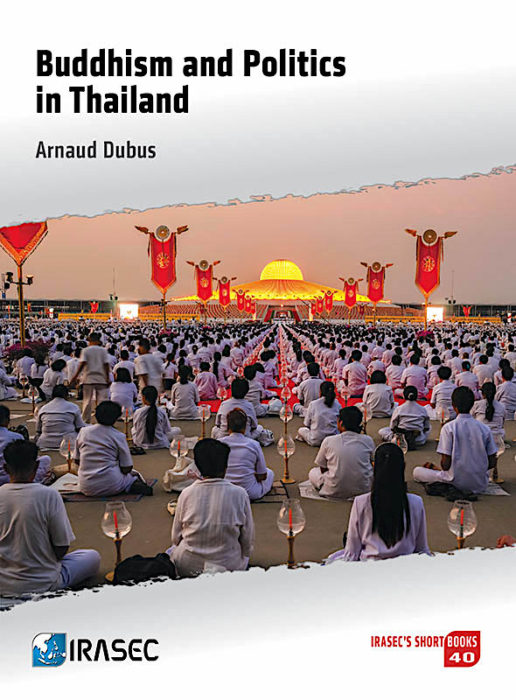

Fortunately, Arnaud was well-versed in Thai history and culture and he was always keen to learn more. He published several scholarly books, including the remarkable “Buddhism and Politics in Thailand” (“Institut pour la Recherche sur l’Asie Contemporaine”, 2018). But that was still not enough to make a living.

Fortunately, Arnaud was well-versed in Thai history and culture and he was always keen to learn more. He published several scholarly books, including the remarkable “Buddhism and Politics in Thailand” (“Institut pour la Recherche sur l’Asie Contemporaine”, 2018). But that was still not enough to make a living.

Today, many foreign correspondents have to take other jobs to make ends meet: translation, teaching, public relations, whatever will cover the next rent. This kind of journalism becomes a side hobby, as it was when the profession was born in the 19th century, only possible for those who have the means and opportunities to live on other resources.

The precariousness of the freelancers’ situation is not merely financial, it’s also legal. For the past thirty years, in December, Arnaud had to go through the painful ritual of renewing his media visa. As freelancers don’t have a work contract with their employers they have to justify their activities to local authorities as best as they can.

Some employers refuse to even provide a letter acknowledging they sometimes use the journalist’s services, for fear it will be used later in a legal battle. Every year, correspondents may be asked to leave the country or to stop working as journalists, whether they are newcomers or long-time expatriates with local families.

Freedom Matters Most

Secretly hurt by the indifference shown by some editors, exhausted by decades of running after assignments, and disgusted by the lack of financial recognition, Arnaud Dubus finally abandoned journalism, like many of his peers, and accepted an offer from the French embassy in Bangkok: to become an assistant spokesperson, on a local contract for a monthly salary of $1,600.

At 55, Arnaud and his wife Noo longed for stability, wishing to buy an apartment, which he could never afford as a free-lancer.

But the transition from press to diplomacy, and the thousands of small, daily humiliations of office life, were too much to bear for this gentle and sincere man, who was unwilling to engage in official discourse. His close friends say he never recovered from leaving journalism. “I realise that freedom is what matters most,” he wrote to one of his colleagues a few weeks before his death.

Arnaud the story-teller, a true bridge of intelligence linking Asia and Europe, has left us. We remain to watch part of our profession’s spirit and ethics die along with him.

His friends and colleagues members of the Union de la Presse Francophone (UPF), Thailand :

Christelle Célerier, Christophe Chommeloux, Yvan Cohen, Olivier Cougard, François Doré, Charles Emptaz, Thierry Falise, Loïc Grasset, Didier Gruel, Carol Isoux, Olivier Jeandel, Olivier Languepin, Régis Levy, Thibaud Mougin, Olivier Nilsson, Patrick de Noirmont, Roland Neveu, Philippe Plénacoste, Pierre Paccaud, Bruno Philip, Jean-Claude Pomonti, Pierre Quéffelec, Vincent Reynaud, Laure Siegel, Stephff, Catherine Vanesse.

25 professionals working for the following media are members of UPF-Thailand: Le Monde, Libération, Arte, Mediapart, TV5, France Télévision, TF1, RTL, BFMTV, L’Express, Gavroche, RFI, Lepetitjournal.com, Thailande-fr, Latitudes, Ouest-France.

The UPF was founded in 1950 and gathers over 3000 journalists in 110 countries. The association aims at defending press freedom and promoting French language in the media.

Thanks to Tom Vater for helping out with the translation from the original version in French.

This article originally appeared in Mediapart. Reprinted with permission of the authors.

Le Club est l’espace de libre expression des abonnés de Mediapart. Ses contenus n’engagent pas la rédaction.

The failure to respond to queries is a common freelancer’s complaint. It’s hard to understand because it only takes a moment to send an email saying “No thanks.” Expecting him to host the reporters sent to put the outlets’ brand on big stories is downright galling.

Hello I am so happy I found your blog, I really found you by error,

while I was researching on Digg for something else, Anyways I am here now and would just like to say

many thanks for a marvelous post and a all round exciting blog (I also love the

theme/design), I don’t have time to read through it all at the minute but I have saved it and also included your RSS feeds,

so when I have time I will be back to read a great deal more,

Please do keep up the great b.

Wow. Such a sad story, even more so for someone apparently so principled, dedicated and caring. I extend my most heartfelt condolences to his family, friends and colleagues.

This is so sad. I remember well having had to suddenly become a “foreign correspondent” in my own country of South Africa when the then government would not allow “real” foreign correspondent in. I worked for a Dutch organisation. I faced violence daily, was a single mother with an infant, and faced jail daily for breaching the media regulations and sending a truthful report out every day. I ask for and was not given, a bullet-proof jacket; insurance; and some promise of legal protection should I be detained. Several journalists in the same position as me had a rough time too. But I loved the work. Then the story died, and so did the newspapers locally when I wanted to write locally. I barely write now. And I miss it all. I feel much for your colleague who evidently had it much worse than I did. It’s all slipping away.

Thank you for your tribute to this hero of the Truth. Please accept my deepest condolences.

In fact, the news services throughout the world are gasping for air — they are smothered by stories of irrelevancies, and by politic lies.

Rest In Peace. ? ? ?

The NY Times and Washington Post have bureaus stretching across the Middle East from Cairo to Kabul. They typically only one or two on the African continent, same with Latin America. I’m sure they have a correspondent or two in South Asia and Southeast Asia, but not many.

Inexpressibly sad – and a condemnation . . .

We live in the End Times . . .

God rest his soul . . .

This is a very important article. It reminds one of Bob Parry’s articles about Gary Webb

Since the MSM and even so-called liberal media do not pay for or publish serious investigative reporting from the field. somehow the alternative press, which itself is strapped for money, must find funding to support these journalists. For example, if, given the low rate of compensation, reposting an article would also compensate the journalist, then hopefully reposts by multiple outlets would help.

But ultimately, if independent journalism is to survive, it comes down to the commitment of the reader – both through direct financial support of fine journalists – e.g., via outlets like Patreon (I think, for example, of Caitlin Johnstone and Patrick Lawrence)- as well as direct financial support of fine alternative news sites- especially those truly on the frontline, such as Consortium News, which reposted this story revealing the hardships faced by Dubus and other serious journalists, and has been in the trenches every day for Julian Assange and Wikileaks.

No one I know of pays for reposts. Indeed, lots of outlets who don’t pay at all want to publish first, and reposters repost without even asking the author’s permission.

Thank you for this article. I am forwarding it on to a number of folks that includes Jon Talton, author of Deadline Man and columnist for the Seattle Times.

My condolences to his spouse and friends. A true loss to the world of truth.

Lamento muito. É horrivel tomar conhecimento, através da notícia da sua morte, das dificuldades financeiras por que passam estes jornalistas. Inadmissível.

É muito triste a sua morte.

Lamento

The death of Arnaud Dubus is another sadly persistent example of the numberless personal tragedies in the ongoing demise of Print Journalism. It’s easy, I suppose, to rail against social media, but if people wanted to read (and know) beyond their feed lots, they would.

Vale Arnaud Dubus, a fine journalist. A tragic and sad loss to his family and to the trade of journalism.

My heart goes out to his loved ones – what can one say ?

We can only stand for him and say No!

And we all know exactly what it is we say ‘No!’ to . . .

So sad to hear this, even though I didn’t know the man. No one should be driven to such despair.

This is truly sad. This man didn’t need drugs for his depression, he needed to be treated like a human being, shown genuine respect and appreciation, and paid a decent salary.

What is happening with freelance journalism is also a symptom of an even larger issue: in a world where appearance and conformity have ideologically replaced freedom of speech/thought, the pursuit of truth and open communication regardless of one’s stance, opinions which balance the loudest narrative (on any level) are quickly losing their relevance.

As humanism continues to be replaced with productivity and as “personality” becomes “ordered and disordered” rather than “individual” and people are no longer “sad” or “in pain” but “depressed” and “mentally ill”, things will only continue to get worse.

I can only concur . . .

I agree. “It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society… To enjoy good health, to bring true happiness to one’s family, to bring peace to all, one must first discipline and control one’s own mind.” Krishnamurti

Our society is so profoundly sick that they now prescribe mind altering drugs instead of encouraging people to change their lives and create a better society.

It is a tragic ending for a very principled man. Unfortunately, today those who lie and play the master’s game are rewarded and compensated, while someone like M. Dubus are left to struggle. As Buddhists would say, I honor the Light within him. His struggles are not in vain.

I do so agree, but we now face now a very dark night indeed . . .

Without a strong public that takes an interest in what is actually going on in regions of the world that are unfamiliar there is no demand for foreign correspondents. My reading of the situation of “news” is that the public wants to be told what to think because searching for truth takes time and passion. You can’t really blame news organizations–they are no longer what the were but, usually, propaganda outlets for various powerful factions often closely linked to intel.

Having said that, hats off to those who have tried to keep up a vigorous press particularly about foreign affairs but it’s the end of an era and the beginning of another. My condolences to those who knew Dubus.

On an unrelated topic, congratulations to ConsortiumNews for making it on a Google blacklist for being a ‘fringe domain’.

You know you are doing something right when Big Brother puts you on a blacklist for wrongthink.

————————————-

According to Google, they are working on developing ways to ensure that algorithms are weeding out inappropriate web answers rather than having to do so manually. The second web answers blacklist, called all_fringe_domains, appears to be an example of this, as it seems to be generated by an algorithm.

A portion of the fringe domains list was shared with The Daily Caller. On it are the American Spectator, Breitbart, Breaking911, the website of pastor Brian Jones, the website of Bring Your Bible to School Day, Consortium News (published by Robert Parry), St. Philip the Deacon Lutheran Church, speakerryan.com, The Franklin Society (a cryptocurrency blog), Free Thought Project, The Gateway Pundit, and The Gorka Briefing.

In addition, several blogs critical of conservatives are on the fringe domains blacklist, including Breitbart Unmasked and Spencer Watch, a blog critical of Jihad Watch’s Robert Spencer.

Google CEO Sundar Pichai told Congress in December that the company does not “manually intervene on any particular search result.” (RELATED: Google Fires Republican Engineer Who Spoke Out Against ‘Outrage Mobs’)

But in fact Google does manually intervene in several different types of special search results, as The Daily Caller revealed in April, through their news blacklist. The web answers blacklist is more evidence that they do manually intervene in particular search results.

Pichai also said in a recent interview with Axios that the company wants to “really prevent borderline content, content which doesn’t exactly violate policies.”

————————————-

https://dailycaller.com/2019/06/11/revealed-two-google-blacklists-fringe-domains-special-search-results/

Somehow, I’m not surprised. Not surprised that Google is being such an a**hole organization, nor that they would put CN on their black list.

The Evil becomes so evident . . .

We all belong to one side of the line or the other . . .

Tragic. And “Buddhism in Thailand” looks like a fascinating book.