After decades of global integration, Dan Steinbock sees imperial presidential policies based on “national security interests” producing majestic mistakes.

How Carl Schmitt Took Over the White House

By Dan Steinbock

Special to Consortium News

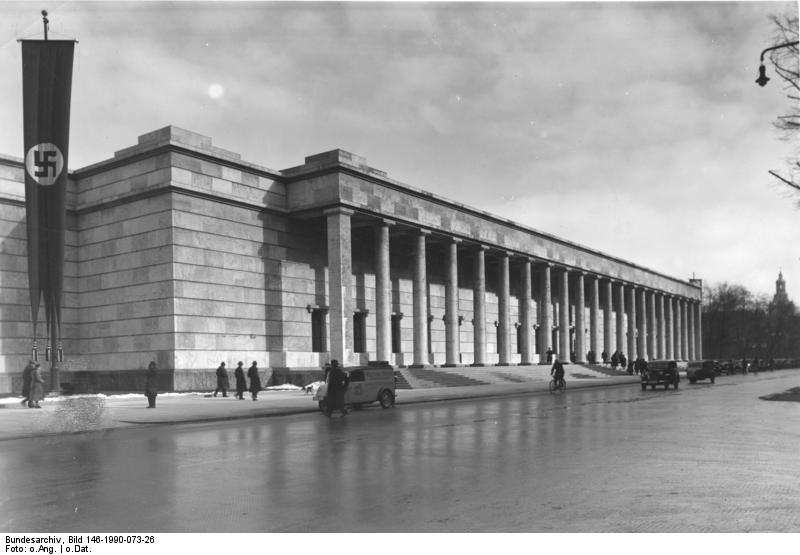

As the controversial German jurist Carl Schmitt saw it in the interwar Third Reich, legal order ultimately rests upon the decisions of the sovereign, who alone can meet the needs of an “exceptional” time, transcending the law so that order can then be reestablished. “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception,” he wrote. “All law is situational law.”

As the controversial German jurist Carl Schmitt saw it in the interwar Third Reich, legal order ultimately rests upon the decisions of the sovereign, who alone can meet the needs of an “exceptional” time, transcending the law so that order can then be reestablished. “Sovereign is he who decides on the exception,” he wrote. “All law is situational law.”

In post-Weimar Germany, such ideas contributed to the eclipse of liberal democracy. Following Sept. 11, 2001, similar arguments renewed neoconservative interest in Schmitt and the “state of exception.” In this world the status quo is in a permanent state of exception, as enemies — “adversaries, others and strangers” — will unite “us” against “them.”

In this view, the U.S. response to 9/11 was not unusual because liberal wars are “exceptional.” Rather, it was a manifestation of ever-more violent types of war within the very attempt to fight wars that would end “war” as such.

Collapse of 2 World Trade Center seen from Williamsburg, Brooklyn. (Pauljoffe, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Similarly, it is politically expedient to legitimize a trade war and other political battles in the name of “national security,” which allows the sovereign to redefine a new order on the basis of a state of exception. Subsequently, a new national security strategy redefines “friends” as “enemies” and “us” as victims who are thus justified to seek justice from our “adversaries” — “them.”

The logic of the state of exception leaves open the question how the White House could establish such a trade war as a sovereign, when such trade wars have not been supported by most of President Donald Trump’s constituencies and have been opposed by much of the Congress and by most Americans.

Unitary Executive Theory

What looms behind the Schmittian White House is a tradition of conservative thought relying on the unitary executive theory in American constitutional law, which deems that the president possesses the power to control the entire executive branch.

The first administration to make explicit reference to the “unitary executive” was the Reagan administration. Typically, the practice has evolved since the 1970s, when President Richard Nixon decoupled the U.S. dollar from the Bretton Woods gold standard and trade deficits began to rise.

The terrorist attacks of 9/11 allowed the George W. Bush administration to make the unitary executive theory a common feature of signing statements, particularly in the execution of national-security decisions, which divided Capitol Hill and were opposed by most Americans.

In the case of Trump, the need for inflated unitary executive power arose with Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, which restricted the president’s strategic maneuverability to operate with the Republican Congress in 2017-18 but permitted actions that required only executive power, typically in tax and trade policy.

In this view, efforts at a U.S.-Sino trade compromise may prove more challenging than anticipated, as evidenced by the extended truce talks. Even a trade compromise may prove unlikely to deter subsequent bilateral technology wars, which have been heralded by U.S. actions in the case of Huawei and longstanding efforts to sustain American primacy in 5G technologies. As U.S. production capacity has been offshored since the 1980s, such efforts rely on national security considerations.

If the trade war is less about trade than about a U.S. effort at economic and strategic primacy, no “concession” may prove enough for the Trump White House, which may be more likely to re-define the status quo on the basis of a national emergency.

‘Costly, Mysterious Wars’

The idea of the “imperial presidency” in America is hardly new, as historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. demonstrated in the Nixon era:

“The weight of messianic globalism was indeed proving too much for the American Constitution .… In fact, the policy of indiscriminate global intervention, far from strengthening American security, seemed rather to weaken it by involving the United States in remote, costly and mysterious wars.”

Please Make a Donation to Our

Spring Fundraising Drive Today!

Ostensibly moderate administrations, including that of President Barack Obama, have conformed to this rule. During Obama’s first term in office, America expanded its military presence in Afghanistan and increased drone missile strikes across Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. The administration also deployed the military to combat piracy in the Indian Ocean, engaged in a sustained bombing operation in Libya, and deployed U.S. Special Forces in Central Africa. In these cases, Obama decided to use force without congressional approval.

During the past half century, amid a series of asset bubbles, a slate of new foreign interventions, the Iraq War debacle and the $22 trillion U.S. sovereign debt, the imperial presidency has become a target of broader criticism. But why has it grown even harder to challenge?

Certainly, one critical force has been campaign finance and the increasing role of “big money” in American politics. In particular, the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, which struck down a federal prohibition on independent corporate campaign expenditures, paved the way for corporate power to override democratic power in the White House.

At the same time, the ultra-rich have begun to play a more active part in politics, with serious consequences for American democracy, as many American political scientists have warned.

In the new status quo, neither 20th century American Empire nor 21stcentury Third Reich is needed for majestic policy mistakes. Imperial Presidency will do. Indeed, even the sovereign’s executive power may suffice.

Emergency Powers in Time of Peace

The uses of executive power are likely to go far beyond the current rivalry for artificial intelligence (AI), as evidenced by Trump’s efforts to re-define, re-negotiate or reject major U.S. trade deals on the basis of national security. By the same token, foreign investment reviews will be overshadowed by national security considerations.

As postwar multilateralism has been replaced with unilateralism, the White House sees itself in international strategic competition with other great powers, particularly Russia and China, yet old allies – including Europe and Japan – are not excluded.

Since the U.S. Constitution ensures the president a relatively broad scope of emergency powers that may be exercised in the event of crisis, exigency or emergency circumstances (other than natural disasters, war, or near-war situations), it matters how the White House chooses to apply its definition of a “state of exception.”

Under the current, wide definition, it is prudent to expect escalated international trade disputes between the U.S. and other members of the World Trade Organization, even against the WTO itself. Citing diffuse national security reasons, the White House defends its tariffs under the GATT Article XXI; the so-called national security exception.

There is a big difference between the repercussions of such executive decisions in the postwar era and the early 21stcentury. In the past, policy mistakes could penalize the U.S. economy and democracy. After half a century of increasing global interdependency, they can derail global economic prospects.

Dr. Dan Steinbock is the founder and director of Difference Group and has served at the India, China and America Institute (U.S.), Shanghai Institute for International Studies (China) and the EU Center (Singapore). For more, visit the Difference Group.

This commentary draws in part from his new analysis, “U.S.-Sino Futures,” released by Chinese Quarterly of International Studies (CQISS).

Please Make a Donation to Our

Spring Fundraising Drive Today!

A to Z:

Our losses are mounting with every passing day.

Free speech, the right to protest, the right to challenge government wrongdoing, due process, a presumption of innocence, the right to self-defense, accountability and transparency in government, privacy, press, sovereignty, assembly, bodily integrity, representative government: all of these and more have become casualties in the government’s war on the American people.

https://www.globalresearch.ca/d-dictatorship-disguised-democracy/5676839

So, should we all get practicing the “Crusader Kings” video game?

There is a series of interviews by Greg Wilpert of Charles Derber up on TRNN right now concerning a new book Derber just collaborated on – “Moving Beyond Fear” – which addresses some of the same issues here, for that portion of humanity which lives in the bottom of the house(s).

The Congress has to put their foot down. They can cut money off and lots of other stuff but as the recent Yemen vote and override failure shows the Congress has all the cojones of a wet noodle.

You’re entirely correct about Congress just offering-up token resistance to the militaristic policies of the POTUS, especially starting after 9/11. I don’t think they’re inclined against it anyway, since so many voters seem to like the “USA! USA! USA!” militarism that saturates us (Note: see ‘bracingviews.com’ for excellent articles on this subject by a former AF major turned college prof). Ultimately it gets back to the eligible voters in this country. IF ~half of them don’t even want to vote in POTUS elections and it’s lower for off-year congressional elections, and about 60% of the ones that do vote want to back retrograde conservatives like St Ronnie, well … then… here we are. Like the alcoholic who can’t ‘kick the bottle’, it’s not exactly predictable what will happen, but with high-certainty it’s going to be negative.

Good all reduction of weapons treaties.

Bad all NWO financial treaties.

The author is badly mistaken to think the constitution grants exception or emergency powers to presidents. The purpose of dividing the powers of government into more than one branch is to prevent claims of, or the actual exercise of sovereign ( read dictatorial ) power. The ‘national security exception’ of trade treaties the author is concerned about are the acts of a duopoly congress rather than a provision of article 2 of the constitution.

The US two party system is unnatural, antidemocratic, anti-republican and may be as fatal to the US republic as the emergency executive power was to the Weimar and some South American republics.

Would 3 or 4 parties have prevented the Iraq war? Probably so, the president the supreme court selected wouldn’t have had a majority in either house. Trump’s further packing of the supreme court required a republican majority in the senate. Three or four parties would prevent the kind of 2 party court packing that prevents an independent court system.

Presidents have a veto power, we are told from the time we are jr. high students, to prevent bad legislation. For 230 years the two (us or them) party system has refused to ask a jury like body if a presidential veto is factually bad.

The 2019 elections in Germany put 6 political parties with 709 members in the Bundestag ( House of Representatives). That is democratic political power (rather than paper prohibitions) that can actually check executive abuse.

https://www.bundestag.de.en/

Treaties are made to be broken. Otherwise the people are ruled by the dead politicians who made the treaty. Can you say no taxation without representation.

The outcome in Germany is roughly the same as if there was but one party. With many parties you must have different forms of the spoil system and the ruling parties are more vulnerable to “erosion”. No system will assure that ethical and/or rational ideas will have their sway, this is why we need people who think, analyze and communicate rather that pretending to do so. That of course includes Consortium News.

The recent parade of democratically elected heads of multiparty democracies ganging up on Venezuela was a poster case for the claim that system alone is far from sufficient. Additionally, it is extremely hard to change the aspect of the system that are in the constitution of USA, so it is more productive to spread good ideas and non-constitutional improvements about limits of franchise, gerrymandering, the weight of money in politics etc.

I would say Trump is the natural (d)evolution of of a country that insists it is surrounded by enemies, with continuous fear-mongering by both parties, with the only real objection to Trump by the militarists of each party is his crudeness and indiscretion in revealing what the US is really about with its coercive pressure on every other country, except its closest ally, Israel, with Trump’s BFF in charge there. Thanks to the two previous administrations, everything is already in place to truly “govern” as if in a state of exception: https://consortiumnews.com/2015/09/12/us-war-theories-target-dissenters/

i’m so old i remember when the prc was not a most favored nation, nor was it a member of the wto.

i remember the selling points to the debate to “ bring china into the “community of nations” “.

we were to re make china in our image, to en rich them so they would naturally shed their totalitarian shackles and turn them into a prosperous democracy. and be our ally against communist russia.

the prc has now selected an emperor for life. the prc is leading the way, with the help of sili con valley, to institute “ social ranking “ for all of it’s subjects.

dear dr. dan,

at what point are you able to admit failure ?

ps are you getting any of that chinese lucre ala uncle joe’s son ?

I still retain the mental memory image of WJ Clinton in the Rose Garden announcing the conferring on China of “most favored trade status” and of his articulation of those very arguments you allude to. To add to what you said, I clearly remember Clinton admitting that the economic and cultural shunning of the past will no longer suffice in treating with China. I must have sensed the immensity of that because of all the stark imagery we’ve been exposed to in our collective cacophony, that one has stuck with me.

You err in stating “such trade wars have not been supported by most of President Donald Trump’s constituencies and have been opposed by much of the Congress and by most Americans”. Progressives have traditionally opposed the WTO and free trade agreements, which have resulted in 10s of millions of lost manufacturing (mostly union) jobs in the US and Canada. Trump ran on stopping this manufacturing exodus to low-wage countries, which allowed multi-nationals to sell the cheap products back to the US tariff-free. Trump’s voters (not Republican or Democrat elites) overwhelmingly support tariffs so that US manufacturers can compete fairly with cheap foreign-made goods. What’s more, despite the hysteria of most economic and financial elitists, Trump’s policies are working. Multi-national corporations, big banks and their congressional acolytes hate this, because the WTO and trade deals allowed them free access to the world with no interference from elected governments, which could be sued for “obstruction”. This global control by multi-nationals is an huge extension of their influence and control over national governments, and enable them to not only pursue their own financial interests, but to control economies, finance NGO, influence media, foment wars, and overturn governments. Donald Trump’s actions on trade and tariffs, pose an immense threat to these globalists.

Adding to my comment above, the hatred of Trump’s policies by globalists was not limited to the US, and the attempts to frame him for Russian collusion extended to intelligence agencies of the UK. This provides some indication of the massive control of multi-national corporations and banks over governments and elections throughout the world.

I am in agreement to some extend, but with some corrections. E.g. WTO etc. were introduced for some good reasons and simply picking fights with literally everybody (increasing Canadians! with people so nice and governments that are so eager to please!?) may lead to precisely those bad consequences that relatively free trade avoids.

But on massive control I am not so sure. Surely, there is hardly a trace of some master minds hidden somewhere and pulling the strings. Master cretins, perhaps. One has to keep in mind that just by perceiving personal interests and following routine you can see a high degree of coordination. As a matter of experiments, slime molds are single cell organism with nary a nerve system, but they can move, creating fruiting bodies and spread spores through collective effort, and that works for hundreds of million of years. In Trump case, he stood out from the multitude of GOP candidates by not repeating precisely the same talking points, and violating a number of shiboleths in the process. In the same time, HRC tends to behave like a good pupil, learning all the shiboleths and pronouncing them exactly right, that was perceived as the proof of her acumen and inevitable victory. From that point of view, British spooks simply tried to ingratiate themselves with the inevitable victor, cells of slime mold moving toward a larger concentration of nutrients.

I tried to find argument contradicting what you write, and I checked in tradingeconomics.com. The picture is mixed, but not truly supporting the success of Trumpian tarifs.

Do we see a “stop of manufacturing exodus”? Anecdotally, I seen some products in Walmart etc. that are “now domestic” but not too much. Additionally, in the same Walmart, I met a living breathing manufacturing worker — we chatted briefly on the possible merits of toasters, I noted that inside they seem all the same and he mentioned that in his factory they do it to (different “quality” of some office supplies).

Positives of Trump economy: unemployment down, wages up but “anemically”. Percentage of GDP from manufacturing seems to edge up.

Negatives: one could not guess that this is manufacturing driven boom. Employment in manufacturing is very anemic (although positive, which is not always the case), and rather disturbingly, trade deficit shooted up. So this seems to be a classic debt driven boom. PERHAPS in anticipation of the future trade surpluses, but I would not bet on it.

Baffling: USA got “full employment” with anemic wages. That can be explained by the increasing skill of American managers in tamping down wage demands etc. But the wages started to perk up too. But this is the baffling part: how manufacturing can expand and revive if everybody got a job? I mean, where are the places where you would wish to open a factory and recruit workers?

I could think about a strategy or two, besides areas where there are closed factories and crappy wages (like the town where my interlocutor lives), but on a major scale, USA wastes a large chunk of the workforce and GDP on clerical work in healthcare that would be severely cut if “single-payer” was introduced. By the way of contrast, the trade wars of Trump seem to have no strategy at all.

I agree. this article never mentions how the Global Power Elite Corporations and individuals strategy is to circumvent all National Sovereign Security and Exception. They have their own Global Exception. Big Money Privilege and it was this way historically and rising.

Your post sir is 100% correct.

In the beginning of this financial mess the multinational corporations were mostly USA corporations. It was the USA government that opened the doors to slave labor and no environmental restrictions through out the globe. It was American corporate greed that has since birthed multinational corporations. This is how and why we have the 1% and the 99%.

America financially is a dead man walking. The two things that allow that dead man to walk are reserve currency status and some 800 military bases around the globe. War on a global scale is coming very soon….

If you think Trump is new or different, you’re outside of reality. Trump is behaving EXACTLY THE SAME as all administrations since FDR died. The only possible difference is that Trump is honestly un-signing treaties instead of calmly and constantly breaking them like the other admins did.

There is an obvious sense that the whole world is bracing for the inevitable “big crash”. The military, financial, and ideological components are inextricably tied and must crash simultaneously. – Not long now, although I’ve been saying that for 3 years, and we must also bear in mind that it (the chaos) will necessarily take longer than that to play out.

The Big Bang or crash will either take some time to play out … or things will very quickly change beyond the imagining of many, Tom Kath.

One hopes (has hoped, for far longer than three years) that sanity prevails.

So far, pathology, demagoguery, deceit, and violence have only doubled-down, again and again.

Deja vu all over again … and again … and again.

One “exceptional” moment after another.

Lied into war …

Torture …

Looking forward not back …

Not politicizing “policy” differences …

Extra judicial killings of U$ citizens

rendering “due process” moot …

Drone warfare …

Libya …

Syria …

And, the empty form of law applied to those “too big to jail”, creating a two-tiered “justice” system, criminal law for the many and tort law for the few …

Now, it is the “right” of “first strike” …

Utter madness prevails and patience is a virtue those of us who have witnessed it most sincerely appreciate, even though it does not radiate from the exceptional and indispensable …

That idiocy extends further in the war against the environment, itself.

If the twin insanities of endless war and the destruction of the environment do not describe total insanity, then one shudders to ponder what does.

Yes DW, you are quite right, it may take some time or happen quickly. Just remember that even a dead thing, and especially a big one, can still stink for a long time.

A lot Americans assumed that they could kill other people, but other people couldn’t hurt them. That’s why the 9-11 bombings were so shocking to people in general. They were no longer invulnerable.

New, improved strategy is to starve other people. That is perhaps safer.

The US Constitution does not in fact permit “exceptional” or “emergency” use of military force beyond repelling invasions and suppressing insurrections. The Constitution prohibits Congress from approving or interpreting any treaty like NATO to permit military action that is aggressive, because that is not within the federal powers. But the Legislative, Executive, and Judicial branches all look the other way, as they are all fully corrupted by economic power.

They are all appointed or elected by money, from the MIC, Wall St, and the Israel lobby. It is the unregulated market economy that has replaced the former US democracy with a dictatorship of the rich, not a theory of exceptionalism. The oligarchy is fully aware that they are traitors in economic war against the United States.

ECEKLPTIONALISM HAS ALWAYHS BEEN THE US MARK

There have been so many cases of excep;tionalism in both American a domestic policy that

it is impossible to number them all.

Native Americans were not, of course, “foreign”. KSlaves were property.

In the area of “aggressive foreign policy” note the Seminole Wars lead with murderous victory

by Andrew Jackson.Congress was not informed prior to the invasion but after in a memo by

then Secretary of State John Quincy Adams. American heroes such as Thomas Jefferson

were congratulatory. Jackson became an iconic American hero,

Se bl an Francis Jennings, THE CREATION OF AMERICA. And other works.(James Earl Weeks and

others on Adams.)

—Peter Loeb, Boston, MA

Good points, Peter. There have long been factions or majorities using special exception concepts to violate the original US isolationism, with little concern for the limitation of federal powers so clear in the Constitution. Because that is a defect of their argument, I would not call it a tradition of the US, to avoid legitimizing it with precedent.

The point being that the clear constitutional limits of federal power to repelling invasion (and suppressing insurrections) are a primary basis for invalidating aggressive wars, AUMFs, and approval or interpretation of treaties like NATO as excuses for aggressive wars serving only factions at the expense of the rest of us. Not that a government fully corrupted by economic power would care for any grounds to do their duty.

Apocalyptic:

Donald Trump as an apocalyptic

Pre-figure or Post-figure

in a New World disfigurement

of the previously Ordered World

into science of TransHumanism

Trump would not be the precursor

of this great transformation / but a

protector of the Human Status Quo

against the bio mechanical androids

looming in the near / present future

of robotics and NWO dehumanization

in the Name of Wealth Creation

and for The Survival of The Fittest. …

WTF Boxerwar? Trump a post apocalyptic pre-figure or post figure in a NWO disfigurement? Sometimes the simplest explanations is the most obvious? That Trump is a Stupid moron, whose not pulling the strings, end of story!

Superb article!

Dan Steinbock has well described Carl Schmitt’s contribution to German law at a time when power also sought to have no constraints of law, domestic or international.

Just as does the U$, today.

The claim of “exceptional times, was made (happily, so it seemed) after 9/11.

Thus was, once again, “all law is situational”, in the eyes of power convinced of its prowess and invulnerability, reanimated like some once-dead monster.

At such times the “law” becomes merely an empty “form” of the law, designed to end the rule of law, as was pointed out at Nuremberg.

Perhaps, the only way to halt the monster now arisen will a similar stern accounting?

This is the Dangerous precedent, highlighted in this article, that this so called “Exceptional Nation” called America has set? It has now torn up all International Laws as mandated by the UN & has decided for itself that it has the divine right as a Sovereign Power, to place itself above International Laws that every other Countries have to adhere to? This supreme arrogance & ignorance of a Rogue Nation, in massive decline as a World Power, was last seen in the rise of Nazi Germany? America, under the imbecilic rule of the Twitter in Chief dotard,Trump, is in effect saying that the International rules based order based on the rule of law, doesn’t matter anymore? These are the actions of a Tyrant, a bully & a clear sign of the moral decay & rot of a Empire that’s clearly on the way out!

Tags: 9/11 Carl Schmitt

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/carl-schmitt

Carl Schmitt and the new Hedonism in the age of Trump.