The Iraq wars and their consequences have been callous, bipartisan campaigns that have profoundly altered Arabs’ views of the United States, says As’ad AbuKhalil.

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

It has been sixteen years since the U.S. invasion of Iraq of 2003. The event barely gets a mention in the U.S. press or is any longer part of American consciousness. Iraq remains a faraway land for most Americans and the remembrance of the Iraq war is only discussed from the standpoint of U.S. strategic blunders. Little attention is paid to the suffering and humiliation of the Iraqi people by the American war apparatus. Wars for Americans are measured in U.S. dollars and American blood: suffering of the natives is not registered in war metrics.

It has been sixteen years since the U.S. invasion of Iraq of 2003. The event barely gets a mention in the U.S. press or is any longer part of American consciousness. Iraq remains a faraway land for most Americans and the remembrance of the Iraq war is only discussed from the standpoint of U.S. strategic blunders. Little attention is paid to the suffering and humiliation of the Iraqi people by the American war apparatus. Wars for Americans are measured in U.S. dollars and American blood: suffering of the natives is not registered in war metrics.

The Iraq calamity is not an issue that can be dismissively blamed on George W. Bush alone. For most Democrats, it is too easy to blame the war on that one man. In reality, the Iraq war and its consequences have been a callous bipartisan campaign which had begun in the administration of George HW Bush and Bill Clinton after him. The war and the tight, inhumane sanctions established a record of punishment of civilians, or the use of civilians as tools of U.S. pressure on foreign governments, which became a staple of U.S. foreign policy.

The U.S. government under Ronald Reagan resisted pressures to impose sanctions on South Africa under the pretext that sanctions would “hurt the people that we want to help”—this at a time when the blacks of South Africa were calling on the world to impose sanctions to bring down the apartheid regime. This was the last time that the U.S. resisted the imposition of sanctions on a country.

For the Arab people, the successive wars on Iraq—and the sanctions should be counted as part of the cruel war effort of the U.S. and its allies—changed forever the structure of the Middle East regional system. The wars established a direct U.S. occupation of Arab lands and it reversed the trend since WWII whereby the U.S. settled for control and hegemony, but without the direct occupation. (The U.S. only left the Philippines because Japan had awarded independence to the country during the war, long after the U.S. failed to deliver on promises of independence).

Washington succeeded in the political arrangement designed by the Bush-Baker team to create an unannounced alliance between the Israeli occupation state and the reactionary Arab regime system, which included the Syrian regime, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Gulf states in the same sphere. This arrangement served to oppress the Arab population and to prevent political protests from disrupting U.S. military and political plans, and to ensure the survival of the oppressive regimes who are willing to cooperate with the U.S. The Syrian regime, which cooperated with Washington in the 1991 Iraq war was even rewarded with control of Lebanon.

But the war on Iraq altered the regional structure of regimes. They were no more split into progressive and reactionary. Syria in the past was associated with the ”rejectionist stance,” even though the Syrian regime never joined the ”Rejectionist Front” of the 1970s led by Saddam Hussein, the arch enemy of Syrian leader Hafidh Al-Asad.

It was no coincidence that the U.S. invaded Iraq and expelled Saddam’s army from Kuwait in the wake of the end of the Soviet Union. The U.S. wanted to assert the new rules just as it asserted the new rules of Middle East politics after WWII when it signaled to Britain in 1956 in Suez that it is the U.S. and not Europe which now controls the Middle East region. Similarly, the Iraq war of 1991 was an opportunity for the U.S. to impose its hegemony directly and without fears of escalation in super power conflict.

The U.S. did not need direct control or colonization after after WWII, with the exception of oil-rich Gulf region. (Historian Daniel Immerwahr makes that argument persuasively in his brand new book, “How to Hide and Empire: A History of the Greater United States.”) After the 1973 oil embargo on Western countries because of U.S. support for Israel in that year’s war, the U.S. military had plans on the books for the seizure of Gulf Arab oil fields. But the significance of oil has diminished over the decade especially as fracking has allowed the U.S. to export more oil than it imports.

Indelible Memory

Furthermore, the previous reluctance of Gulf leaders to host U.S. troops evaporated with the 1991 war.

But the memory of that first Iraq war remains deep in the Arab memory. Here was a flagrant direct military intervention which relied for its promotion on a mix of lies and fabrications. The U.S. wanted to oppose dictatorship while its intervention relied on the assistance of brutal dictators and its whole campaign was to—in name at least—to restore a polygamous Emir to his throne.

The U.S. also bought about official Arab League abandonment of Israel’s boycott, which had been in place since the founding of the state of Israel. As a reward for U.S. convening of the Madrid conference in 1991, Arab despots abandoned the boycott in the hope that Washington would settle the Palestinian problem one way or another. Yet, the precedent of deploying massive U.S. troops in the region was established and the U.S. quickly made it clear that it was not leaving the region anytime soon. Regimes that wanted U.S. protection were more than eager to pay for large-scale U.S. military bases to host U.S. troops and intelligence services. But that war in 1991 was not the only Iraq war; in fact, Washington was also complicit in the 1980-1988 Iraq-Iran war, when it did its best to prolong the conflict, resulting in the deaths of some half million Iraqis and Iranians.

U.S. Marine artillerymen set up M-198 155mm howitzer against Iraqis during Operation Desert Storm. (Wikimedia Commons)

The invasion of Iraq in 2003 was not about finishing an unfinished business by son toward his father. It certainly was not about finding and destroying WMDs. And no one believed that this was about democracy or freedom. The quick victory in the war of Afghanistan created wild delusions for the U.S. war machine. Bush and his lieutenants were under the impression that wars in the region could be fought and won quickly and on the cheap. The rhetoric of “the axis-of-evil” was a message from the U.S. to all its enemies that the U.S. would dominate the region and would overthrow the few regimes which are not in its camp. The quick “victory” in Kabul was illusory about what had just happened in Afghanistan. Seventeen years later the U.S. is now begging the Taliban—which it had gone to war to overthrow—to return to power to end the agony for U.S. troops and for U.S. puppets in the country who are terrified of the prospect of a country free of U.S. occupation.

Iraq created new images of the U.S.: from Abu Ghraib to the wanton shooting at civilians by U.S. troops or by contractors, to the installation of a puppet government and the issuance of capitalistic decrees and laws to prevent the Iraqi government from ever filing war crime charges against the occupiers. Arabs and Muslims developed new reasons to detest the U.S.: it is not only about Israel anymore but about the U.S. sponsorship of a corrupt and despotic regional order. It is also about Arabs witnessing first hand the callous and reckless forms of U.S. warfare in the region. Policy makers, think tank experts, and journalists in DC may debate the technical aspects of the war and the cost incurred by the U.S.. But for the natives, counting the dead and holding the killers responsible remains the priority. And the carnage caused by ISIS and its affiliates in several Arab countries is also blamed—and rightly so—on U.S. military intervention in the Middle East.

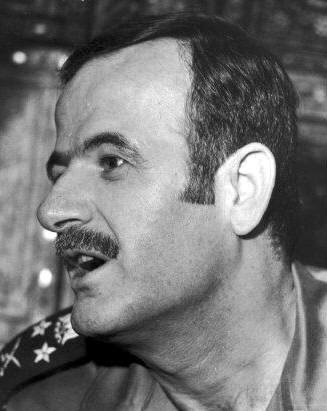

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science atCalifornia State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

If you value this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one.

Until some years ago I think to american people as ignorant and not culprit, now time make me change opinion, american people is culprit of complicity with the cabal, the banksters, wall street crime syndicate, the zionists, IsraHELL and all the international multicorporations which make american people everyday more poor . . . .

American people complicity with murders, criminals, exploiters, thieves of lands and resources sovereign of other countries and whatever crime they committed in more than 75 years, also thinking of americans are culprit also of start two world wars.

the empires fall sooner or later, it is a question of seeing how strong the thud will be, and how many guilty must be hanged in the square … maybe in Nuremberg!!

Nothing surprising but the former Commander of the (British) Royal Navy, Admiral Lord West, has just (a couple of days ago) told the Daily Mail that he was ordered to prepare for the invasion of Iraq in June 2002, after the Camp David meeting between W and his enabler Tony Blair.

West said that he ordered the Royal Marines to prepare and that the government spent the following months putting together a propaganda campaign in an attempt to cobble together a Casus Belli that could be taken to Parliament.

Lord West sits in the House of Lords as a Labour member.

Anyone who still believes that the imperialists were merely mistaken in their WMD propaganda -still the Democrat position I believe- is deeply deluded. The US went to war to confirm its hegemony. The UK went to war because its shabby, cowardlyleaders lacked the dignity and integrity that was necessary to rebuff Bush and the coterie of thugs and clowns in his court.

I would agree with those who recognise that Asad is an ornament to this site and recall, with affection, his legendary blog.

All US wars since 1950 have been murder campaigns to satisfy the vanity & blood lust of Americans, leaders & ordinary people alike. The Iraq Wars have been among the worst examples.

The older I get and the more I read US & world history, the more I’m coming to the conclusion that the US is — at heart—- as bellicose as any other country, but it’s aggressiveness is often elevated by the 1.) US historical roots in slavery, native genocide, gun violence, hucksterism, and land-theft traditions, 2.) geographic isolation from major powers during the world-wars — much less these smaller wars — gives the US population a severe detachment from the massive destruction of wars, 3.) religious beliefs that enable many US residents to not worry about all the innocent deaths they’re enabling (‘all those innocent dead people are going to heaven unless they’re non-Christian in which case they’re going to Hell anyways, so forget about them’). Hard to envision a peaceful solution, but I won’t vote for any war-mongers for POTUS.

The U.S. is the worst of all the war-making nations. It is the root of all evil. Its citizens must recognize this if anything is ever to change.

Good comment, but by definition any POTUS becomes a war monger or they get the JFK treatment.

The article really demonstrates the depravity of the supposedly “Exceptional US Empire” & its utter failure to win a lasting peace, anywhere it invades? It may win a initial invasion but can’t maintain the occupation against a low tech, determined foe? Now they are having to resort to begging the Taliban, the very low tech enemy their been fighting & losing too for 17 yrs, if they can call it quits so the American losers can, like their predecessors did in Vietnam, run like hell to depart with their tails between their legs in utter humiliation! And regarding the Middle East, the blowback & damage to its reputation that America has done, with its illegal interventions & murderous actions against Arab Nations & their people in Iraq, Iran, Syria, etc has achieved the opposite result of what they envisioned? The fabricated lies & American excuse for invasions have now galvanised & caused former enemies to form new alliances to fight American tyranny. One example is former enemies Iran & Iraq now working together to thwart American objectives & turning to Russia & China to frustrate the US Imperial plans. These middle East Nations from Iran to Syria have succeeded & kept the Empire fighting & bleeding the US of Morale, money, treasure & resources & manpower until they are totally bankrupting themselves? $6 trillion dollars of wasted American MIC spending for nothing to show for it but contempt & hatred by Arabs towards them & a a$22 Trillion dollar deficit & endless deficits in the foreseeable future which is going to bankrupt the Empire! But now that the US Empire has disastrously lost the Syrian Regime change War, its now time to scurry back like a rat leaving a sinking ship to the America’s & create more chaos again by doubling down with more lies to now invade Venezuela in yet another failed Regime change op run by psychotic despots such as Pompeo, Bolton & Abrams under the auspices of the most corrupt criminal Dictator, President Trump! Russia is now intervening & supporting Maduro thus thwarting the Criminal actions of the US Empire like they did in Syria! Why doesn’t this stupid American Nation & its idiotic Leaders ever learn from its hopeless History of failure? That’s truly the definition of insanity, as Einstein stated, doing the same thing, over & over & expecting a different result? But that’s what you would expect of a late stage, declining, dying Hegemonic Empire such as the US? The US Empire & especially the Emperor is the last to know it has no clothes because its blinded by its own arrogance, hubris & stupidity that it can’t acknowledge the reality of its situation! What’s the situation? The US Empire is done & dusted & its unipolar moment in the sun has ended! The sooner it wakes up to that fact & reality the better for it will be for itself & its people, but that will never happen, it would rather burn everything to the ground rather than face the truth & rejoin the Human race!

american deserves EVERYDAY one Hurtgen Forest to conquer . . . . .

Asad I miss a lot your blog , which I read every day ,will you come back ?

Thanks, Halima. It took so much time to do. I now write on FB and Twitter and also write a biweekly article here and a 2400 words weekly article for Al-Akhbar. Pressed with time but really appreciate your interest.

I miss the blog also but I’m glad you are here and at Al-Akhbar. If I was healthy enough I thought of traveling over to SSU to may be catch a lecture or two.

Muslims got played in Iraq. I remember in the first few years the US couldn’t even go outside the green zone without getting shot or bombed. The resistance against the occupation was united.

But later the US managed to rile up divisions between Shia and Sunnis, turning them against each other. With a bunch of false flag bombings against Sunni and Shia mosques by their special forces (like those 2 British SAS who got captured wearing beards near the bomb site), a united war of resistance against US imperialism suddenly turned into a stupid “sectarian conflict” against each other.

Even the current conflict between Iran and the Saudis, all had their root causes there. It’s unfortunate so many Muslims even today do not realise this.

The obsession to rule the world poisons everything the US does outside it’s borders – and inside those borders as well. When the American government says it wants to help another country, it really means they seek to impoverish and destroy it.

Yes, the result of an unregulated market economy, in which business bullies rise to the top and buy elections and mass media to install the tyrants of oligarchy. The very lowest characters have risen to the highest powers and have denied us democracy; they attack the world for personal gain and glory.

I recall hearing that before the attack on Iraq they actually considered calling it Operation Iraqi Liberation but they decided the acronym was just too much of a giveaway.

I can’t tell you the number of times I’ve said, what about the people that live there? What about all the innocent people we’re killing? Does no one care about them? More bluntly, how many thousands of people have to die to avenge the deaths of 3,000 odd people in NYC on 9/11/01? The United States seems to need to kick somebody’s ass all the time. I strongly suspect that our sudden desire to control Venezuela is as a result of figuring out that we were being ousted from Syria by Russia. I’ve often wondered what the pebble in the emperor’s shoe would be. It appears to be the Middle East.

– Russia is in Venezuela with troops and equipment (maybe not a lot, but they’re there). They are ignoring the screeches of Revoltin’ Bolton and Pompous. And their response to yet another threat of sanctions, roughly translated, was we fart in your general direction.

– The US is down to 400 troops in Syria. That will certainly be contested in the UNSC by Syria and we’ll have to see but the vassal states of Britain and France are likely to block any rebuke to the US but the UNGA is a different matter.

– As noted, the Taliban are once again ascendant in Afghanistan. The thing to remember about the Taliban is that they are Afghans. Their religious affiliation won’t affect that. The Taliban is unlikely to bail the US out. They are more likely to keep up Afghanistan’s historic role as the graveyard of empires.

– Hypocrisy is being outed! First, Italy broke with the EU and signed an MOA with China on the BRI project. This will be a major step in defanging the Washington regime as the IMF and the WB will become less important. France and Germany, in keeping with vassal status, immediately criticized Italy only to be reminded of their own multi-billion dollar deals with Beijing. Next thing you know, Germany and France are negotiating their own MOA with China, something that Washington will have nothing to do with Washington is losing control over its vassals.

– More people are suggesting that the UN should investigate US war crimes in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Afghanistan. Of course Revoltin’ Bolton and Pompous immediately said that such weasels as would investigate the US would be denied visas. What’s it going to take to get the UN relocated from NYC?

Cheney helped to bring down the towers.

And speaking of France and Germany, during the Iraq War in 2003, both vassals opposed the Iraq War, leading to American and British media to pillory them (especially France), accusing them of either treason (anti-Americanism in this case) or cowardice (parroting the repetitive “we saved your sorry arse (twice)” excuse), as well as the occasional accusation of anti-Semitism. Any mention of “Freedom Fries” or the Boycott-France campaign (anyone remember them?) in the American press or consciousness would be (is?) just as rare, if not more so, than any mention of the Iraq War.

What added salt into the wound in the case of Britain was its already-existing anti-French sentiment, especially with tabloids such as the Daily Mail. I doubt the average reader of such a rag would accept that, if it weren’t for the “Frogs”, they would be dying of food poisoning since there would be no Louis Pasteur to discover pasteurization, and millions of blind folks would be bereft of a proper tactile writing system without Louis Braille. Also, many words that most Anglophones take for granted nowadays are of French origin, some of which having the same original pronunciations. For this reason, in early 2017, this former Anglophile lost faith in Britain.

They say that resorting to ad hominem attacks is a sure sign that you’ve lost an argument. If all the Anglo-American media could do was to attack France and Germany just for the crime of having second thoughts, then it would be no wonder the Iraq War failed.

A very good article; the perspective of the victims is usually lacking in Mideast reportage.

Here’s the last part of Lissa Johnson’s series on war propaganda, Julian Assange, and how it works:

https://opensociet.org/2019/03/27/the-psychology-of-getting-julian-assange-part-5-war-propaganda-101/

O Society, I love reading your links, posts, etc. They are inspiring, so illuminating and very entertaining. You are a terrific poster here at CN. Thank you. M.