Recently published book by Carter official says the president was initially hostile to Sadat’s initiative toward Israel because Carter saw it as “the end of any hope of a comprehensive peace,” says As’ad AbuKhalil in this review.

Carter Worried Bilateral Israel-Egypt

Deal Would Undermine Regional Peace

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

One would think there isn’t anything new to be said about the Camp David negotiations of 1978. There are enough books about the accords and about Egyptian-Israeli peace to fill a book case.

One would think there isn’t anything new to be said about the Camp David negotiations of 1978. There are enough books about the accords and about Egyptian-Israeli peace to fill a book case.

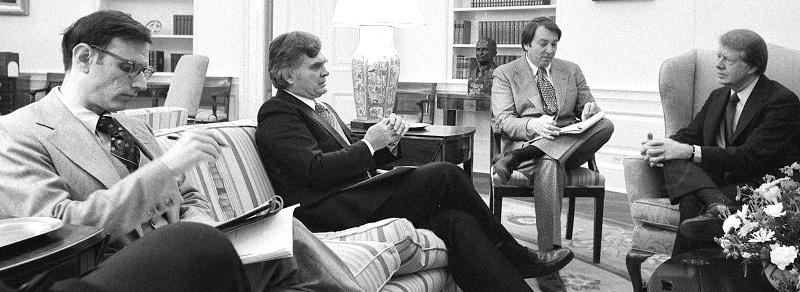

But the recent book by Stuart Eizenstat, President Carter: the White House Years (Thomas Dunne Books, 2018), adds information and insights to the plethora of works on the subject. It’s clear Eizenstat, a domestic policy advisor to Jimmy Carter, kept copious notes (as detailed as the notes of H. R. Haldeman in Nixon’s White House) during his years of service. And he supplemented his account by conducting interviews with Carter and other U.S. and foreign officials.

This book could emerge as one of the definitive accounts (in over a 1000 pages) of the Carter White House years, as far as the Middle East is concerned. Eizenstat was heavily involved in Mideast policy making though he wasn’t a specialist in foreign policy. But the administration relied on him as a liaison with U.S. Jewish organizations and as a back channel to the Israeli government.

Eizenstat admits “there is no other issue in American foreign policy where domestic politics intrudes more directly than the Middle East” (p. 409). While Eizenstat has a record of staunch support for Israel and hostility to its enemies—whoever they are—he does offer a few criticisms of the Israeli lobby and of the Israeli government.

At a time when Rep. Ilhan Omar has been accused of anti-Semitism merely for suggesting that AIPAC uses its financial muscle to promote its congressional agenda, Eizenstat’s statements in this regard would have been characterized as anti-Semitic if articulated by Omar or her other fellow Muslim representative, Rashida Tlaib.

He says he helped draft a speech on Arab-Israeli issues to be delivered in “New Jersey,” he wrote, “because it would be crucial to Jews in key northeastern states, as well as Florida and California” (p. 412). Of course, one can’t today speak of a “Jewish lobby.” It could be perceived as anti-Semitic. It’s also inaccurate because the pro-Israeli lobby extends far beyond the Jewish community.

Evangelical Christians, on the whole, appear to be more fanatical supporters of Israel than Jewish Americans. On the subject of Israel, there is more diversity of opinion inside the Jewish community than there is among Southern Baptists.

Carter Camp Divisions

The book explains clearly that the administration was divided between two camps: National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance. Vance was motivated more by human rights while Brzezinski spoke for a less pro-Israeli foreign policy, largely from the standpoint of securing Arab support against the USSR.

Domestic policy advisors were solidly in support of the traditional pro-Israel line because they feared the impact on Carter’s prospects for re-election. Carter wavered between the two groups, Eisenstat writes. But he eventually surrendered to Israeli dictates in the negotiations. Even that wasn’t sufficient politically: Carter was perceived as hostile to Israeli interests and his support among Jewish voters, according to the author, plummeted to 40 percent in 1980.

Eizenstat reveals that Carter was initially hostile to Sadat’s initiative toward Israel in November 1977 because the president saw it as “the end of any hope of a comprehensive peace and will result only at best in a bilateral agreement between Egypt and Israel.” (p. 472). Carter was right but he went along with the initiative anyway.

Eizenstat’s account reflects the typical American bias of favoring pro-U.S. despots over despots who are not aligned with the U.S. Egyptian dictator, Anwar Sadat, receives glowing treatment by the author—who bizarrely insists on referring to him as “general” (p. 430) when Sadat never commanded troops in his life and his military role in his youth was rather minimal. It is possible that Eizenstat was deceived by Sadat’s fancy and elaborate military uniform, which was designed for him by Pierre Cardin.

Worse, he glosses over, or ignores, the anti-Semitism of Sadat, who referred to the Israeli lobby as “US Jews lobby” (p. 482), and who designed his overture toward Israel purely out of his “perception of the political influence of American Jews.” (p. 471) But what is disturbing is that Eizenstat justifies Sadat’s famous admiration for Hitler by maintaining that it was “less for his violent anti-Semitism than his opposition to the British.” (p. 430).

But that lame excuse could apply to the meeting between Hajj Amin Husseini (leader of the Palestinian national movement prior to the founding of the state of Israel) and Hitler, which has been used for decades to discredit the Palestinian national movement and to frame it as anti-Semitic. If the opposition to the British was the motive for Sadat’s admiration for Hitler, could that factor not also apply to Hajj Amin too? Surely, Hajj Amin could not admire the Nazi ideology where Arabs were perceived as an inferior race, described by Hitler as “painted half-apes.” And if the author describes Hafidh Al-Asad of Syria as a “brutal dictator”—which he was—he should have used the same term for Sadat.

3-Way Special Relationship

The author does not shy away from underlining the role of the Israeli lobby. He refers to the “special triangular relationship among Israel, the American Jewish leadership, and the Congress in effectively applying pressure on the presidency to modify U.S. policy to Israel’s benefit.” (p. 437). If Ilhan Omar or another Arab member of Congress were to offer such an explanation of the role of the lobby there would have been a hue and cry and calls for resignation. And Eisenstat was wrong in referring exclusively to the Jewish leadership in this regard when Evangelical Christians have become the guardians of Likud interests in the Republican Party.

Eisenstat, however, does not shy away from expressing outrage at Israeli interference in U.S. domestic politics; he writes about Moshe Dayan’s offer to help Carter with his domestic problems, “This was an amazing intrusion into domestic politics by a foreign minister, even from a friendly country,” Eisenstat writes (p. 466).

The author reinforces the view that then Israeli prime minister, Menachem Begin fiercely defended the interests of the occupation state during the Camp David negotiations, while Sadat was casual about the whole process and disregarded his own advisors when they tried to defend Egyptian interests and sovereignty.

It also becomes clear that the PLO’s stance against Sadat and the talks was correct and that neither Sadat nor Begin were serious about offering meaningful sovereignty to the Palestinian people. While Carter initially sought to offer political rights to the Palestinians, he quickly abandoned the goal once he saw that Sadat and Begin were only interested in a bilateral agreement.

Eisenstat confirms that Begin did indeed lie to Carter: that he initially offered a settlement freeze for 5 years not for 3 months—as Begin later claimed. The author says that Carter took this lie as a personal insult and it affected his view of Israel, although he never spoke about that while president. What is disturbing about this book is that Eisenstat confirms what we have known all along: that the idea of a Holocaust museum (which came out of the office of Eisenstat during Carter’s administration) was not motivated by a desire to inform Americans of the horrific tragedy, but was instead a cynical manipulation of “Jewish American voters” who were disenchanted with Carter(p. 487).

This book underlines the devastation that the Camp David accords afflicted on the Middle East region. The U.S. secured the withdrawal of Egypt and its army from the Arab-Israeli conflict in order to permit Israel to commit more aggression and occupation against a variety of Arab territories without worrying about retribution from the Egyptian army. Far from being proud of his peace achievement, Carter should be ashamed of his role in brokering an expensive bilateral treaty—against the wishes of the Egyptian people, and contrary to the vision of a Palestinian “homeland”–which Carter had promised back in March 1977.

As’ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the “Historical Dictionary of Lebanon” (1998), “Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism” (2002), and “The Battle for Saudi Arabia” (2004). He tweets as @asadabukhalil

If you value this original article, please consider making a donation to Consortium News so we can bring you more stories like this one. Please give to our end-of-year fund drive, by clicking Donate.

I agree with this, Camp David was really a terrible setback for an overall peace agreement.

Sadat did something that I think Nasser would have never done. He gave the Israelis even more leverage than they had before the Yom Kippur war.

Ah, come on, DH Fabian, the Jews didn’t live in Palestine, an Arab country, for over 2800 years until they decided it was “theirs” in 1948, given to them by the British, who as was their attitude, arrogant enough to think they could willy nilly give away another people’s land to rid Europe of Jews and leave them, the British, with “clean hands.”

BTW, the Jews in Israel are not Semites, or at least very few who are the descendants of the 5% who were in Palestine when the British gave it away; those few live near Tel Aviv and refuse to be called anything but Palestinians and fly the Palestinian flags and claim to be Palestinians, not Israelis. The Semites are the Arabs. The Jews are from Europe, Russia, Poland, Lithuania, the United States and are mainly Ashkenazis, and not Semitic.

Quite Right!

In the 1870’s, an American Doctor of Divinity, the Reverend Richard Newton visited Palestine.

He started his visit at Jaffa where he was impressed by the fertility of the land around the town.

“…..you find that the town is surrounded by beautiful orchards and groves of olives trees, oranges, lemons, citrons and apricots, which make the country around look like one great garden……”

On setting out from Jaffa to visit Jerusalem, the Reverend gentleman continued to describe the countryside.

“ Our road lay first across the level plains that surrounded Jaffa. These are very fertile and under high cultivation. Jaffa is famous for its oranges. They are the finest raised anywhere in this part of the World, and the extent to which they are cultivated surprised me greatly. For a long time after leaving the town, we rode along through a constant succession of vast groves of orchards of orange trees. I never saw such a profusion of this delightful fruit. The trees were loaded with them. They hung thick upon the bending branches in every stage of growth ………the air was perfectly redolent with the delightful fragrance…”

Leaving behind the Jaffa district, Reverend Newton continued on his journey.

“ After passing out from those beautiful orange groves, the country became more undulating. The soil has a dark rich look, and broad fields of luxuriant grain spread out on every hand, and gave substantial and satisfactory evidence that it really was as rich and fertile as it appeared to be.”

So, no Palestine desert then? and it must be remembered by us all, that this was 1870.

No Zionists were there, no militant Jewish ‘settlers’, just ordinary Palestinian farmers peacefully tilling their land as they had done for well over a thousand years!

Even now one can see how few Jewish people actually bother to read their own history. They do not even read their own historians, such Prof.Shlomo Sand’s and his well-researched books. Every hstory is mainly based on stories and myths, changing thorughout the history of every people, but the Jewish people in recent years or decades have really literalized every symbolic story to concrete, simplistic ideas about ownership.

Prof Sand is a healthy, realistic thinker with his The Invention of the Land of Israel (instead of these fundamentalist crowd who think they had a right to oppress another people).

Hannah Arendt too warned for the militarization and nationalism, which has led to this new form of fascism.

Anybody watching what’s happening in Great Britain with the Labour Party? Icke has a lot to say about that at youtu. be/hL 3g2FsWrqg (put it all together to access).

https://www.bnaibrith.org/press-releases/ambassador-stuart-e-eizenstat-addresses-bnai-brith-award-for-journalism-recognizing-excellence-in-diaspora-reportae-for-2012

https://sites.google.com/site/thecampaignerunbound/home/b-nai-b-rith-british-weapon-against-america

As a former New Yorker who recently moved to the deep south (south of Georgia) I have become fascinated with southern history. Especially with regards to the US Civil War. That second link has a wealth of information. One mind boggling factoid, that during the US Civil War General Grant had B nai B rith members arrested as agents for the British. Clearly, Eizenstat, like Kissinger , were “Hofjuden” (Court Jews) for this long standing Anglo American eastern establishment running this shadow government . Then, during the US Civil War and during the Nixon and Carter years. I mean how incredible is the fact that during the Civil War The British were instrumental in the assassination of Lincoln? John Wilkes Booth clearly, coming from the prominent British Booth family. Who today is represented by Tony Blair’s wife Cheri Booth Blair.

That second link is really worth your time to peruse. The south during the Civil War was deeply aligned with Britain. Conversely, the north had a relationship with Czarist Russia. Seward’s folly was Russia selling Alaska to the US to keep it out of the hands of the British. That old Great Game in effect for all to see.

Thank you As’ad for reading this 1000 page book for us.

This isn’t about an oppressed race seeking to regain their country. Palestine was simply the name of the historic Jewish (not Arab) nation, which was restored in part, and renamed Israel, in 1948. Jews are, indeed, indigenous to that bit of land. The youngest person born in Palestine would be in his 70s today. Those called “Palestinians” today are Arabs who are recruited to work toward the destruction of the sole Jewish nation. Note that Israel is roughly 1% of the Mideast region, with the remaining 99% owned by the various Arab countries. It’s a tiny country, roughly the size of New Jersey. The “Palestinian issue” if about the effort to take ownership of that remaining 1%. We don’t all agree that a “fair partitioning” of the Mideast would be: 100% for the Arabs, 0% for the Jews.

It is mostly Zionist nonsense, but Fabian added some original balderdash. Palestine was a Roman name derived from inhabitants who descended from Philistines. Actual inhabitants had a variety of backgrounds, and at the time there were pagans, Jews and Samaritans, descendants of “10 tribes”. Jews were very “energetic” after revolting against Seleucids and subjugated the others, with some massacres, discrimination against Samaritans and forcible conversions to their religion, e.g. pagan Edomites were converted. Then they got themselves Edomite kings who were “good Jews” but that time, but rather tyrannical, so Jews asked Romans to be ruled directly. Romans agreed. While Romans were not engaging in massacres like Herodian kings, they were collecting taxes, Jews did not like it so they rebelled twice and were expelled. Samaritans were not expelled, but over the centuries the bulk of them converted to Christianity and, later, to Islam.

In any case, if expelling and/or subjugating inhabitants after “1800 years of absence” is justifiable, Vandals should get Poland back, the Welch should get England (restoring Arthurian kingdom), Mons should get Thailand and Burma, Turks should go back to Mongolia etc. This is total nonsense.

Hmm … informative post. Although I know the ‘basic outline’, you added some new information that I will research. Your last para is particularly astute. There is such a thing as ‘the reality on the ground’, and like it or no, Israel has created a reality through it’s various machinations.

However, those machinations eventually resulted in a demarcation that omitted the West Bank and most of the Occupied Territories. While I agree with you that restoration of ‘historical homelands’ for all and sundry is an impossible outreach, Israel should be compelled to withdraw to it’s agreed – 1967 – borders.

Someone waaay wiser than I said that “Countries do not have a right to exist, but people do.” That makes a lot of sense to me. If a country has a ‘right’ to exist, then the Confederate State of America should still be kicking. It ain’t. The Ottoman Empire should still be printed on the map. It ain’t. Ditto for the USSR, the Vandals and the rest of your mentioned gone-aways.

Simply putting your name on a map does not impart immortality.

Good post Piotr. However, DH is impervious on this topic. His teacup is full, no more will go in.

The idea that evangelical Christians are “have become the guardians of Likud interests in the Republican Party” may be true in a superficial sense. But does the Angry Arab really believe this constituency has determined this position on its own?

Nonsense.

The Evangelical portion of the Israeli 5th column is a group of useful idiots. They don’t make policy, nor do they have any real influence. They’re just the muscle, if anything.

I have noticed a number of columnists, particularly “lite” Zionists, trying to sell the same theory of Evangelicals pushing allegiance to Israel. This subterfuge is a way of pretending that bloodthirsty (Jewish) Zionist hoodlums are really just along for the ride and that they have little influence.

The fact that the Angry Arab seems to agree with this ludicrous trope is a sad commentary on his ability to discern the truth.

The interests of the Evangelicals in the Mideast concern access to/ownership of a number of religious (tourist) spots.

It’s time to define evangelicals. Either they are rural rubes or urban sophisticates. Rural rubes would fit your scenario Mathazar of useful idiots. I tend to define these evangelicals as urban quasi educated quasi sophisticates with prep school, private school backgrounds. Mike Pence would represent that group. White trash rural bumpkins sheepishly follow, in lock step, their pastoral private schooled shepherds like Pence. Private schooled evangelicals and their secret societies have everything to gain from the Zionist Entities success whereas the rural rubes gain nothing from Israel’s existence only what their shepherds tells them.

The Angry Arab, a questionable title for someone who lives and teaches in Modesto, California, has long had a problem with recognizing the power and influence of the Israel Lobby.

He was quick to republish and endorse the incredibly nonsensical critque of the Mearsheimer and Walt essay on the Israel Lobby a decade ago by a Palestinian professor from Columbia, Joseph Massad, that ran on CounterPunch.

Massad had been previously persecuted by a Lobby organization and apparently hoped to get it off his back by bashing the two professors, who unlike him, had the courage to tell the truth about the lobby’s power in the US, particularly with regard to the Iraq war.

After I had written a paragraph by paragraph response to Massad that ran on Dissident Voice, a debate was arranged between me and a partner, Palestinian professor Hatem Bazian, a major voice for Palestine from UC Berkeley against the Angry Arab and Stephen Zunes, a long time apologist for AIPAC.

Just a few days before the event which was to take place at USF, where Zunes teaches, the debate organizer learned, second hand, that Abukhalil had pulled out, without informing him and that he would only participate in the debate if the question was changed to make the Lobby the ONLY factor in determining US Middle East policy.

Since it isn’t we refused and the organizer was fortunate to get a replacement who, like Zunes, proved ineffective in defending the Lobby’s position. I then wrote a follow-up for CounterPunch entitled, “The Missing Abu-Khalil.”

It’s strange the book or this article doesn’t mention Kissinger. I believe he played a large and cynical role in all this.

When it comes to actually leading on the world stage the US is a load of amateurs. Unable to accurately predict the consequences of their actions and typically assuming that what they want to occur is what will come in the wake of our actions, the US has hosed things up time and again.

I wonder if they are making honest predictions, or if their underlying goal is chaos instead of bringing “freedom and democracy”, or fighting “terrorists”. I know the hard line Zionists are happy so long as muslims are killing each other. I suspect the same is true of the PNACers in DC. They also target anyone trying to bypass the almighty dollar as the world’s reserve currency, with mixed results because of big time players like Russia and China.

In this case, Carter did predict correctly, but expedience took priority. Between AIPAC, preference for Jews (familiar to American) over Arabs (strangers) within USA, anti-Communism etc., Carter made his choice in spite of what he predicted himself.

Thank you, Dr AbuKhalil, for this essay into one of the many dark periods of Anglo-American interference in the Middle East and acquiescence to Israel’s perpetual refusal to recognize Palestinian rights (to their land, their homes, their equal humanity). From the Balfour Declaration (a travesty of justice and an arrogance of peculiarly western, British, Orientalism, if ever there was one) to today.

And particular thanks for your raising the hypocrisy involved with the pro-Israel condemnation of the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem’s contact with Hitler (no similar condemnation, to my knowledge ever cast at Americans who admired the man, nor of those members of the British royal family who were out and out supporters of fascism, Nazi style).

Regarding the deal made between Sadat-Begin-and Carter, it might be described instead of better than nothing as worse than nothing. Instead of one jailer of the people in Gaza, it gave us two. It gave Carter the Nobel Peach Prize along with Menachem Begin. Is Carter ashamed of the agreement he made as the author suggests he should be? Is he ashamed of buying into Brzezinski’s plan for destroying the Afghan society to get back at the USSR? A guess is that Carter applied a politician’s version of integrity to both and believed he did the right thing.

As to the author’s statement that the Jews are more critical of Israel’s behavior toward the Palestinians and other Arab neighbors than the Evangelicals, that may be true. Unfortunately, to date those Jews who speak out against injustice have little say in our policies in the Middle East. There is reason to hope that this will change.

Thank you Herman and As’ad AbuKhalil for helping us sift through the complexity of US interference in Middle Eastern Issues. Years ago I recognized what I saw as the odd bias that Zbigniew Brzezinski seemed to place on all policy decisions. I finally concluded that he seemed to be fighting a kind of personal battle against the Soviet Union so that all geopolitical decisions reflected his anti-Soviet bias. In time, I realized that Henry Kissinger had a similar and long term bias. Between those two individuals and a series of poor leaders, we can see the total mis-direction of American Foreign Policy. President Carter still eludes me. Was he duped or was he incapable of seeing through the subtrafuge?

I know what you mean about Jimmy Carter. I think he was duped by Brzezinski. He seems to me to be the only president in my lifetime since JFK who has any moral character whatsoever. That’s probably why he only got one term.

Thank you Skip Scott. Hopefully we will be able to clarify these inconsistencies soon…