In a strangely old-school, Catholic, sense, they chose not to look back or question the assassinations of the 1960s, writes Edward Curtin.

By Edward Curtin

edwardcurtin.com

Growing up Irish-Catholic in the Bronx in the 1960s, I was an avid reader of the powerful columns of Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill in the New York newspapers.

Growing up Irish-Catholic in the Bronx in the 1960s, I was an avid reader of the powerful columns of Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill in the New York newspapers.

These guys were extraordinary wordsmiths. They would grab you by the collar and drag you into the places and faces of those they wrote about. Passion infused their reports. They were never boring. They made you laugh and cry as they transported you into the lives of real people. You knew they had actually gone out into the streets of the city and talked to people. All kinds of people: poor, rich, black, white, high-rollers, lowlifes, politicians, athletes, mobsters — they ran the gamut. You could sense they loved their work, that it enlivened them as it enlivened you the reader. Their words sung and crackled and breathed across the page. They left you always wanting more, wondering sometimes how true it all was, so captivating were their storytelling abilities.

They cut through abstractions to connect individuals to major events such as the Vietnam War, the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy and his brother Robert, the Central Park jogger case, AIDS. They were spokesmen for the underdogs, the abused, the confused and the bereft. They relentlessly attacked the abuses and hypocrisies of the powerful.

They became celebrities as a result of their writing. Breslin ran for New York City Council president along with Norman Mailer for mayor with the slogan “No More Bullshit.” Breslin appeared in beer and cereal commercials. Hamill dated Jacqueline Kennedy and the actress Shirley MacLaine. Coming out of poor and struggling Irish-Catholic families in Queens and Brooklyn respectively, they became acclaimed in NYC and around the country. As a result, they were befriended by the rich and powerful with whom they hobnobbed.

HBO has recently released a fascinating documentary about the pair: “Breslin and Hamill.” It brings them back in all their gritty glory to the days when New York was another city, a city of newspapers and typewriters and young passion still hopeful that despite the problems and national tragedies, there were still fighters who would bang out a message of hope and defiance in the mainstream press. It was a time before money and propaganda devoured journalism and a deadly pall descended on the country as the economic elites expanded their obscene control over people’s lives and the media.

Irish Wake

So, it is also fitting that this documentary feels like an Irish wake with two wheelchair-bound old men musing on the past and all that has been lost and what approaching death has in store for them and all they love. While not a word is spoken about the Catholic faith of their childhoods with its death-defying consolation, it sits between them like a skeleton. We watch and listen to two men, once big in all ways, shrink before our eyes. I was reminded of a novel Breslin wrote long ago: “World Without End, Amen,” a title taken directly from a well-known Catholic prayer. Endings, the past receding, a lost world, aching hearts and the unspoken yearning for more life.

Hamill, especially, wrote columns that were beautifully elegiac, and his words in this documentary also sound that sense despite his efforts to remain hopeful. The film is a nostalgia trip. Breslin, who died in 2017, tries hard to maintain the bravado that was his hallmark, but a deep sadness and bewilderment seeps through his face, the mask of indomitability that once served him well gone in the end.

So, while young people need to know about these two old-school reporters and their great work in this age of insipidity and pseudo-objectivity, this film is probably not a good introduction. Their writing would serve this purpose better.

Assassination Investigations

This documentary is appearing at an interesting time when a large group of prominent Americans, including Robert Kennedy Jr. and his sister Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, are calling for new investigations into the assassinations of the 1960s, murders that Breslin and Hamill covered and wrote about. Both men were in the pantry of the Ambassador Hotel when Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in 1968. They were friends of the senator and it was Hamill who wrote to RFK and helped persuade him to run.

Breslin was in the Audubon Ballroom when Malcolm X was assassinated. He wrote an iconic and highly original article about the JFK assassination. Hamill wrote a hard-hitting piece about RFK’s murder, describing Sirhan Sirhan quite harshly, while presuming his guilt. They covered and wrote about all the assassinations of that era. Breslin also wrote a famous piece about John Lennon’s murder. They wrote these articles quickly, in the heat of the moment, on deadline.

But they did not question the official versions of these assassinations. Not then, nor in the 50-plus years since. Nor in this documentary. In fact, in the film Hamill talks about five shots being fired at RFK from the front by Sirhan Sirhan who was standing there. Breslin utters not a word. Yet it is well known that RFK was shot from the rear at point-blank range and that no bullets hit him from the front. The official autopsy confirmed this. Robert Kennedy Jr. asserts that his father was not shot by Sirhan but by a second gunmen. It’s as though Hamill is stuck in time and his personal memories of the event; as though he were too close to things and never stepped back and studied the evidence that has emerged. Why, only he could say.

Too Close to the Events

Perhaps both men were too close to the events and the people they covered. Their words always took you to the scene and made you feel the passion of it all, the shock, the drama, the tragedy, the pain, the confusion, and all that was irretrievably lost in murders that changed this country forever, killings that haunt the present in incalculable ways. Jimmy and Pete made us feel the deep pain and shock of being overwhelmed with grief. They were masters of this art.

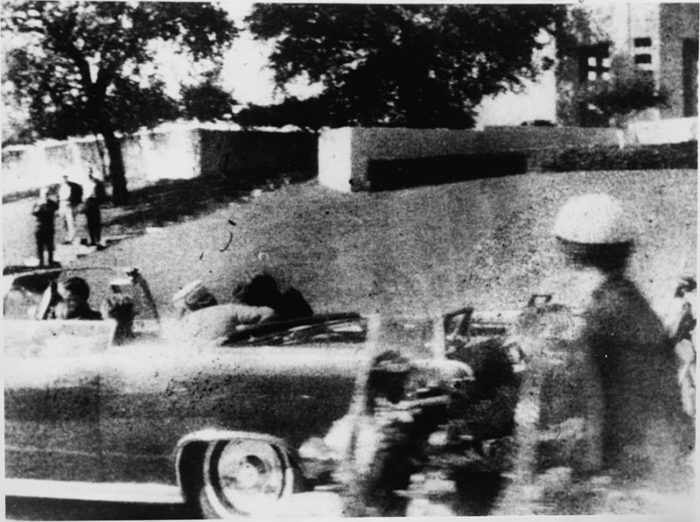

Mary Ann Moorman’s Polaroid photograph of the assassination of President Kennedy, taken an estimated one-sixth of a second after the fatal head shot on Friday, Nov. 22, 1963, Elm Street, Dealey Plaza, Dallas. (Wikimedia)

But the view from the street is not that of history. Deadlines are one thing; analysis and research another. Breslin and Hamill wrote for the moment, but they have lived a half century after those moments, decades during which the evidence for these crimes has accumulated to indict powerful forces in the U.S. government. No doubt this evidence came to their attention, but they have chosen to ignore it, whatever their reasons. Why these champions of the afflicted have disregarded this evidence is perplexing. As one who greatly admires their work, I am disappointed by this failure.

Street journalism has its limitations. It needs to be placed in a larger context. Our world is indeed without end and the heat of the moment needs the coolness of time. The bird that dives to the ground to seize a crumb of bread returns to the treetop to survey the larger scene. Breslin and Hamill stuck to the ground where the bread lay.

At one point in “Breslin and Hamill,” the two good friends talk about how well they were taught to write by the nuns in their Catholic grammar schools. “Subject, verb, object, that was the story of the whole thing,” says Breslin. Hamill replies, “Concrete nouns, active verbs.” “It was pretty good teaching,” adds Breslin. And although neither went to college (probably a saving grace), they learned those lessons well and gifted us with so much gritty and beautiful writing and reporting.

Yet like the nuns who taught them, they had their limitations, and what was written once was not revisited and updated. In a strange, very old-school Catholic sense, it was the eternal truth, rock solid, and not to be questioned. Unspeakable and anathema: the real killers of the Kennedys and the others. The attacks of Sept. 11, 2001 as well.

When my mother was very old, she published her only piece of writing. It was very Breslin and Hamill-like and was published in a Catholic magazine. She wrote how, when she was a young girl and the streets of New York were filled with horse-drawn wagons, the nuns in her grammar school chose her to leave school before lunch and go to a neighboring bakery to buy rolls for their lunch. It was considered a big honor and she was happy to get out of school for the walk to the bakery she chose a few streets away. She got the rolls and was walking back with them when some boys jostled her and all the rolls fell into the street, rolling through horse shit. She panicked, but picked up the rolls and cleaned them off. Shaking with fear, she then brought them to the convent and handed them to a nun. After lunch, she was called to the front of the room by her teacher, the nun who had chosen her to buy them. She felt like she would faint with fear. The nun sternly looked at her. “Where did buy those rolls?” she asked. In a halting voice she told her the name of the bakery. The sister said, “They were delicious. We must always shop in that bakery.”

Of course, the magazine wouldn’t publish the words “horse shit.” The editor found a nice way to avoid the truth and eliminate horse shit. And the nuns were happy.

Yet bullshit seems much harder to erase, despite slogans and careful editors, or perhaps because of them. Sometimes silence is the real bullshit, and how do you eliminate that?

Ed Curtin teaches sociology at Massachusetts College of Liberal Arts. His writing on varied topics has appeared widely over many years. He states: “I write as a public intellectual for the general public, not as a specialist for a narrow readership. I believe a noncommittal sociology is an impossibility and therefore see all my work as an effort to enhance human freedom through understanding.” His website is http://edwardcurtin.com.

Very good thought.

Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone.

James Earl Ray, acting alone.

Sirhan Sirhan, acting alone.

What’s to investigate?

And, none of this is new.

Contra the febrile imagination of Gore Vidal, John Wilkes Booth acted “alone” with his associates; neither Jeff Davis nor Republican Radicals were behind him. A political assassination like that of Sirhan Sirhan.

McKinley and Garfield were killed by nuts. basically like JFK and MLK.

As for RLK Jr’s claims? He’s an antivaxxer quack, among other things.

(sigh)

JFK… RFK… JFK Jr. … Mel Carnahan… Paul Wellstone… Tom Daschele anthrax… Building # 7…

A picture of Jimmy Breslin and Norman Mailer campaigning in NYC

https://www.facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10218896457392302&l=5a59cc8a70

Sometimes the obvious is so starkly in front of our faces it is self-imploded as a self-protecting, sanity-preserving defensive mechanism, and oh how this is this such a case for that in how we’ve blanked-out the obvious, shrouded it in the darkness of “NO, OH NO! NO! NO!” lifetime invisibility; completely blacked it out in cognitive dissonance when something as horrible as a much-beloved President is gunned-down right in front of a nation’s eyes.

November 22, 1963 is seared into our minds, those of us alive and cognizant of our larger surroundings at the time, on That Day.

But the most obvious proof of all that it was the work of a team is right there, on film, and cannot be readily-apprehended unless one is familiar with ballistics and what high-powered rifle bullets do in both entry and exit wounds.

I am familiar with this from over a lifetime of hunting (for food) in Alaska and it astounds me that this point has not been raised after all of this time, especially in a nation full of hunters back then. I can only account for our multi-generational hypnosis with the Allen Dulles-influenced (controlled?) Warren Report by reason of mass confirmation bias— we “needed an official word” for national closure and one that most would find reasonably palatable to the senses and so we got what the conspirators dished out in our national trauma and ongoing shock’s healing such as it was and has become. So that produced the “lone, deranged, politically-inspired” (huh?-just how, why, and for what?) ex-Marine sharpshooter–and that right there tells you he wouldn’t have depended on a piece of shit WW II Italian bolt action, notoriously-inaccurate weapon if he were actually serious.

There’s that and the fact Lee Harvey Oswald had worked in the Office of Naval Intelligence (spooks!) and much more of interest, but I’ll not go further down that path or that the Presidential limousine was summarily “disappeared” rather than being subject to forensic reports and released photographs, nor that the Dallas PD and Texas State Troopers had crime scene jurisdiction, but were shoved right out of the way.

No, I’ll leave you with the actual confirming and damning evidence that the “lone gunman” theory as fact would deny the laws of physics as I have observed them so many, many times, and without fail.

The back of John F. Kennedy’s skull was destroyed and blown BACKWARDS some 15 feet in what ONLY can be conclusively described as an exit wound. Remember Jackie’s frantic action crawling BACKWARDS over the trunk in a primally-inspired first reaction to put her husband’s head back together again?

JFK was killed by a round fired from the front.

Test

I learned today the lady in polka dot dress witnessed running down back stairs calling out they’d shot Robert, was most likely Elayn NEAL, and that her husband, Jerry Capehart had worked cia mind control.

All dead now, of course.

Like these two you write of.

Like us, sooner or later.

But every day we learn a little more. Every day. And every day mainstream doesn’t talk about it, doesn’t put its best and brightest directly at the enormity of information PROVING the conspiracies, PROVES the conspiracy. Intell/deepsnake HAS to create their next memory hole attack dogs NEWSGUARD® and the Integrity Initiative † to keep their gigantic psyop in motion through the laughable google and fb feeds,because they know damned well how much is out there and how much it adds up.

Thank you remorris, here is a truly great book that helps solve the case…

https://www.amazon.com/Polka-File-Robert-Kennedy-Killing/dp/1634240596/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1550460092&sr=1-1&keywords=the+polka+dot+file

I would like to bring up a point related to the acceptance of official stories and refusal even to allow discussion of alternatives. The US Congress introduced “the Magnitsky Act in 2012 and has since used and enlarged it to punish Russian “evildoers” as decided by the USA, based on the story by hedge fund manager/fraudster William Browder. Robert Parry has written extensively in CN on this. Ever since the film by Andrei Nekrasov cast doubt on the “facts” of the case (“The Magnitsky Act-behind the scenes” in 2016) this film has been stopped from all its programmed showings, it is almost never available online, it cannot now even be seen as video on demand, vimeo no longer even admits to it. If it is so revealing and refutes the arguments of Browder (the only person giving his point of view, in the USA, Europe and in the UK where Browder has been welcomed) it cannot just be his money keeping an effective rebuttal of all the alleged crimes of the Russian State in this case from even being examined by the public. Is this more serious, since so many forces seem to be involved in ensuring this cannot be viewed?

rosemerry-

I believe it is still possible to view the film if you email fredrik@hinterland.no, unless vimeo has deleted it altogether. I got to see it by sending a request to one of the producers at the email address above, and he got back to me after about a month. He sent me a link and requested that I send him my cellphone number so he could text me a p/w to access the film. It is worth the effort to see it.

Browder represents western capitalism, aka rape, pillage and plunder. It is not just Browder, it is the entire corporate run empire he is a part of, that continues to punish Putin’s Russia for seeking partnership rather than serfdom.

Thanks, both rosemerry and Skip,

Here are a couple of good ones on that subject, and I have plenty more bookmarked.

https://www.voltairenet.org/article168007.html

https://www.voltairenet.org/article30105.html

I am able to find it on Reelhouse.org for $6.69 per view.http://www.magnitskyact.com

With respect, I disagree that “silence” on JFK/RFK assassinations by Breslin and Hamill was “real bullsh%t” and otherwise grist for such severe criticism. 1. Who knows–perhaps they had no strong grounds to diverge from the two “one shooter” governmental conclusions. 2. Like many of us, they may have held suspicions that others were similarly motivated; but, they had no strong proof to put such theories forth as fact-based opinions. 3. Given the close personal attachments, maybe Breslin and Hamill did not feel they could write on such explosive fact-intense topics with the necessary dispassion (indeed it’s hard to think of close friends who did fan the conspiracy flames; family members I place in a different category). 4. Maybe Breslin and Hamill decided to let the families speak for themselves and not interject out of respect. 5. Any combo and/or all of the above.

Having followed the careers of these two greats for many years, I very strongly doubt that they withheld expressing serious conspiracy thoughts out of fear of personal harm. One who conjures such absurdism really does not understand the generous humanity of these two.

In this regard, I suggest we stick to the known facts of their journalism, namely, that Breslin and Hamill parked their personal passions at the gate, as their profession demanded, and for the ages impressed on all the legacies of these two men, by their remarkable street reporting, which helped the nation share in the magnitude of the losses. Let’s remember them by what they did write.

Neither Breslin nor hamill was known for their analysis. They gave quick passionate insightful perspectives on the news. They did not do investigative journalism.

Very well stated. As a New Yorker who grew up reading these 2 writers, I agree with you, 100 %.

Consider the possibilities. What are the prospects for a journalist who reveals people who’d just killed a President?

If they would not stop at that, why would the journalist expect to survive?

If they knew, they’d know not to say.

Then again, maybe they knew there was nothing to know.

We can’t tell which from their silence. Both reasons would predict the same outcome.

“The Notable Silence of Jimmy Breslin and Pete Hamill”

In the matter of America’s 1960s assassinations these journalists were no different than all the rest.

American journalism, virtually in its entirety, avoided the assassinations, at least in any serious way.

And, the truth is, you really could not get published if you did, at least anywhere “respectable.”

The few Americans who took a serious look at the assassinations were not journalists, people like Sylvia Meagher or Mark Lane.

One exception was well-known dirt-digger, Dorothy Kilgallen, who promised publicly to bust the case wide open. She died shortly later in very suspicious circumstances.

One journalist, not an American, did take a very serious look at Kennedy’s assassination. Anthony Summers wrote the best book ever written on the subject about forty years ago, “Conspiracy.”

You might enjoy this little piece on the most significant piece of paper ever released by the folks releasing old assassination documents.

I think it especially notable that it was virtually ignored by American journalism.

https://chuckmanwordsincomments.wordpress.com/2018/07/13/john-chuckman-comment-the-first-genuine-information-in-the-kennedy-assassination-records-release-to-give-us-some-genuine-information-about-what-happened/

As for American “journalism” on Kennedy’s death, you might enjoy this:

https://chuckmanwordsincomments.wordpress.com/2017/03/08/john-chuckman-comment-old-phony-and-cia-shill-dan-rather-cited-second-time-recently-against-trump-fake-news-from-one-of-the-corporate-presss-old-experts-in-fakery-the-record-on-the-zapruder-fil/

But Breslin’s good friend Norman Mailer did look closely at the JFK assassination in “Oswald’s Tale” and concluded he acted alone.

Yes, and his payback was all the help he could get for his giant CIA pudding book.

No honest investigator could possibly conclude what Mailer did.

Besides, Mailor was actually a pretty undistinguished man in his basic views, in his Americanness.

Despite being a drama queen like Trump and making lots of noise, he was, in fact, about as much a rebel or an independent-minded investigator as Mike Pence.

Thank You Ed Curtin,

I Learned a lot here about writers Pete Hamill and Jimmy Breslin and from the comments from some very smart readers here.

I know a thing or two about Cover-ups of the terrible things that happen with official and media help. I know is that writers, politicians and anyone important enough to bring out more truth is overly cautious and has reason to be afraid of what it will do to their position and to be attacked as “Conspiracy Nuts” from the right, left and middle of the Political Culture. These crimes are ordered with patsies set-up to blame by Pros who know the shield of “National Security” will protect them.

And from my experience this goes for friends and family much too often when you realize how few want to get involved with a search for the truth and speak out and act in some even reasonable way to find the truth behind the cover-ups. To me it seems a too universal truth that this fear is what keeps the Powers That Be no matter what system or nation on earth in control of our lives but less so, the more we fight that fear.

JFK did not like our involvement in Vietnam and pulled out “advisors” as fast as he could. The CIA murdered him so that LBJ could start the war and Texas companies could profit in the billions.

That’s obvious.

See:

https://chuckmanwordsincomments.wordpress.com/2018/07/13/john-chuckman-comment-the-first-genuine-information-in-the-kennedy-assassination-records-release-to-give-us-some-genuine-information-about-what-happened/

No, JFK was a war hawk initially, had a change of heart, but was afraid to pull out until after the 1964 election, thinking he would lose the Election if he lost the Bay of Pigs and Viet Nam.

Divide and conquer is a strategy used by Europe’s crowned bloodsuckers (British & Vatican slave masters) for centuries. This, to weaken their feudal underlings. Make no mistake it is a war between the rich and the poor. British and Vatican slave masters, in eternal struggle against slaves trying to better themselves.

Growing up in a New York Irish Catholic neighborhood during the post war years of relative economic security, I came to recognize this riff between the rich and the poor. Rich Anglos vs. poor Irish. It was simple back then.However,as the years went by something else was taking place. Corruption was a tool used by the rich to compromise the poor. Buying off your enemies is a very old tool indeed. Factionalism became the reality. Privileged poor waged war against the underprivileged poor. A story as old as time. Factions of privileged poor will sell their souls to the devil to maintain their new found prosperity. Even if it means destroying their underprivileged poor relations.

I’m not sure Breslin and Hamill are representative of these new compromised factions emerging in all ethnic communities. But I think I can say someone like Peter King could be.

My own experiences with determined IRA supporters declaring their support of Menachem Begin because Begin bombed the English in the King David Hotel became my own wake up call to an unsettling information campaign far more sophisticated then anything I ever dreamed of. Old corrupt NewYork city alliances took precedence over doing the right thing. Sadly, support of Zionism was support of Anglo Imperialism. The privileged poor with their quasi superior educations should have been aware of that. Some may have been but most were not.

Clearly, the British and Vatican slave master utilize a complex multi layered divide and conquer strategy in all or most of the diverse ethnic communities of New York.Factionalism occurred within the New York Jewish community as well. Again, poor Jews were deeply resentful of rich Anglos (poor Jews and poor Irish Catholics contempt for rich Anglos….. really a very old New York city tradition). While conversely, rich Jews had deep hidden alliances with this old world of rich European crowned bloodsuckers.

A troubled economy may unravel these factional divides keeping the rich safe from harm. Although it seems fairly bullet proof from where I stand. Money the root of all evil.

The IRA was infiltrated and compromised before it existed, when it was the IRB. Very well researched book on it is “Fenian Fire” by Chirstie Campbell, a tale about Civil War veterans being lured to England to create mayhem in England and fight for a United Ireland (kept them from attacking Canada as they’d wanted to do). If they had managed to create a “United Ireland” it would have been an historical first as they have been fighting each other since time in memorial. The “enemy”, be it the Danes, the Normans, Cromwell or the Orange Willie only need to go in and tip the scales to keep the divisions and blood flowing. e.g. just prior to WW1 Erskine Childers provided 10,000 pounds worth of out of date weapons to the southern Catholic Irish (he then went back to his job at the Admiralty i.e. British Intelligence), while Carson was supplied with 100,000 pounds worth of modern weapons and allowed to create army divisions. The southern Irish was not permitted to create divisions during WW1.

My Dad – an IRA supporter – used to hit the roof when ever Menachin Begin came on TV, but he had been an officer in the British Army in Palestine during the end of the mandate, he lost troops and some of them were hung and bobby trapped. He described it as being sent to a war zone with your hands tied behind your back… but he still resolutely and absolutely supports the Queen! Irish logic!

A complex generation! Being a Pete Hamill myself, and the son of a Pete Hamill (my Dad), I too have been bewildered by the inconsistencies and contradictions embodied in the Irish Catholic psyche. And the Irish Catholicism’s Irish component in our family is very firmly detached from Ireland itself as the family story goes that our ancestor was dragged from Ireland in chains destined for the Caribbean and a life of slavery, and ended up in American “from the beginning”… so that would have to be early 17th C!

My great-Grandfather and his son (both James Hamill) returned to the UK at the end of the 19th century and were, according to the family stories, in the IRA, with James the younger reputed to have led a troop of “Yorkshire Irishmen” to Dublin for Easter 1916.

A good example of a contradiction is my fathers unbending support for the IRA and a Catholic Ireland (we lived in New Zealand), while at the same time professing an undying loyalty to the Queen of England (he gave his oath of allegiance to the king as a WW2 soldier). He would even write to her to tell her that her British Army was occupying Northern Ireland – as if she did not know already.

I still haven’t figured it out, my Dad has never been able to explain the contradiction(s), but will fight for them and defend them to the death… although when he took himself to Belfast to confront an Orange Order meeting he ended up giving himself a heart attack and was carried from the scene in an ambulance, which probably saved him from a fight to the death – which is what he is capable of.

To the best of my knowledge, none of my ancestors have lived in Ireland for a very long time (e.g. around 400 years).

Small correction, that should be “My great-great-Grandfather and his son…” para 2, and “America” rather than “American” para 1.

P.S. I’d be very interested in hearing from any US Hamill’s who have a similar story re-arrival in America, although it does seem to be a fairly common surname over there.

I have come to the belief that people choose to buy into phony narratives because, it makes them feel included and comfortable with the establishment. That for them to step outside of the norm is a dangerous undertaking of sorts. Although while these same people snicker at me for believing that JFK, RFK, MLK, Malcom X, plus 9/11 was a conspiracy these same friends fall for this Russia Gate silliness. Again as you all know the Russia Gate story is manufactured and endorsed by our country’s Powers to Be and there it is, these rather intelligent friends of mine accept that phony narrative lock stock and barrel. But they never question or, dare to ponder, the idea that JFK nor the other great leaders I mentioned earlier were done in by the Deep State. Which raises another question as to who are the real patriots? The citizen who questions the official narrative or, the citizen who jumps on board no matter what the phony lie is our masters & mistresses are selling us these days?

Thanks Joe for printing these articles you have graced this website with. Great job to you and your crew. Joe

Thank you for writing in one succinct paragraph what I struggle to put into words, and what frustrates me to no end.

While it is true that plenty of stupid people graduate from college no less stupid than when they entered, no one will convince me that a ‘diamond in the rough’ doesn’t emerge with more brilliance than might have otherwise been the case. Sure, there have been a few reporters who achieved great things without that benefit – George Seldes comes to mind. But Seldes was an American who spoke German at a time when an interview with Paul von Hindenberg could make all the difference in the world. While Hamill and Breslin may have ‘written’ prolifically, I wonder whether they ‘read’ extensively. A catholic upbringing may produce ‘good boys’. That would seem to include an aversion to questioning authority, which may have contributed to the widespread tendency to ‘cover up’ inarguably predatory behavior with feigned moral ambiguity. Having lived through the assassinations of the sixties, I find it hard to believe that ‘deep thinkers’ wouldn’t at least harbor some healthy skepticism about government involvement. These two were ‘pleasers’, not prophets.

Sy Hersh’s advice to young journalists : “Read before you write.” Reporters no longer do in depth research, or go outside the six owner “bubble” of official narratives.

I suspect that that nun had a pretty good idea of what had happened, but said what she said to make the girl happy. If I’m right, that was a good nun.

Great story about the nuns and the horseshit. Very funny. Noun, verb, object.

Very enjoyable article all around.

“Yet bullshit seems much harder to erase, despite slogans and careful editors, or perhaps because of them. Sometimes silence is the real bullshit, and how do you eliminate that”?

I’ve thought about your question for years Edward Curtin, as I sought answers to the assassinations of the Kennedy brothers. For me the answer is that as a believer in the basic honesty of our system of law and politics, one has to first suspend skepticism, not an easy thing. I achieved this state over years of vacillating between buying the Warren Commission Report and then reading the latest new take. Slowly and yet inexorably I realized the absolutely huge and devious extent of obfuscation. Oliver Stone’s movie was the tipping point for me, followed by the viewing of the Zappruder film reviewed by Geraldo Rivera. From there there was no turning back. At each breakthrough, the outrageousness Of the Crimes become more unimaginable, the body count more stunning. It’s been “a process” but hugely important and rewarding. Many Thanks for your own years of reporting…