Special Report: Many Americans simply view North Korea and its leaders as “crazy,” but the history behind today’s crisis reveals of a more complex reality that could change those simplistic impressions, as historian William R. Polk explains.

By William R. Polk

The U.S. and North Korea are on the brink of hostilities that if begun would almost certainly lead to a nuclear exchange. This is the expressed judgment of most competent observers. They differ over the causes of this confrontation and over the size, range and impact of the weapons that would be fired, but no one can doubt that even a “limited” nuclear exchange would have horrifying effects throughout much of the world including North America.

A Korean girl carries her brother on her back, trudging past a stalled M-26 tank, at Haengju, Korea., June 9, 1951. (U.S. military photo)

So how did we get to this point, what are we now doing and what could be done to avoid what would almost certainly be the disastrous consequences of even a “limited” nuclear war?

The media is replete with accounts of the latest pronouncements and events, but both in my personal experience in the closest we ever came to a nuclear disaster, the Cuban Missile Crisis, and from studying many other “flash points,” I have learned that failure to appreciate the background and sequence of events makes one incapable of understanding the present and so is apt to lead to self-defeating actions. With this warning in mind, I will recount in Part 1 how we and the Koreans got to where we are. Then in Part 2, I will address how we might go to war, what that would mean and what we can do to stay alive.

Throughout most of its history, Korea regarded China as its teacher. It borrowed from China Confucianism, its concepts of law, its canons of art and its method of writing. For these, it usually paid tribute to the Chinese emperor.

With Japan, relations were different. Armed with the then weapon of mass destruction, the musket, Japan invaded Korea in 1592 and occupied it with more than a quarter of a million soldiers. The Koreans, armed only with bows and arrows, were beaten into submission. But, because of events in Japan, and particularly the decision to give up the gun, the Japanese withdrew in less than a decade and left Korea on its own.

Nominally unified under one kingdom, Korean society was already divided between the Puk-in or “people of the North” and the Nam-in or “people of the South.” How significant this division was in practical politics is unclear, but apparently it played a role in thwarting attempts at reform and in keeping the country isolated from outside influences. It also weakened the country and facilitated the second intrusion of the Japanese. In search of iron ore for their nascent industry, they “opened” the country in 1876. Hot on the Japanese trail came the Americans who established diplomatic relations with the Korean court in 1882.

American missionaries, most of whom doubled as merchants, followed the flag. Christianity often came in the guise of commerce. Missionary-merchants lived apart from Koreans in segregated American-style towns, much as the British had done in India earlier in the century. They seldom met with the natives except to trade. Unlike their counterparts in the Middle East, the Americans were not noted for “good works.” They spent more time selling goods than teaching English, repairing bodies or proselytizing; so while Koreans admired their wares all but a few clung to Confucian ways.

China’s Protection

It was to China rather than to America that Koreans turned for protection against the Japanese “rising sun.” As they grew more powerful and began their outward thrust, the Japanese moved to end the Korean relationship to China. In 1894, the Japanese invaded Korea, captured its king and installed a “friendly” government. Then, as a sort of byproduct of their 1904-1905 war with Russia, the Japanese seized control, and, in accord with the policies of all Western governments, they took up “the White Man’s burden.” American politicians and statesmen, led by Theodore Roosevelt, found it both inevitable and beneficial that Japan turned Korea into a colony. For the next 35 years, the Japanese ruled Korea much as the British ruled India and the French ruled Algeria.

A map of the Korean Peninsula showing the 38th Parallel where the DMZ was established in 1953. (Wikipedia)

If the Japanese were brutal, as they certainly were, and exploitive, as they also were, so were the other colonial powers. And, like other colonial peoples, as they gradually became politically sensitive, the Koreans began to react. Over time, they saw the Japanese intruders not as the carriers of the “white man’s burden” but as themselves the burden. Some Koreans reacted by fleeing.

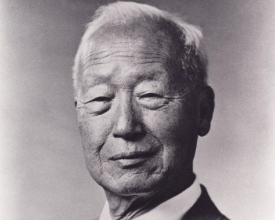

Best known among them was Syngman Rhee. Converted to Christianity by American missionaries, he went to the West. After a torturous career as an exile, he was allowed by the American military authorities at the end of the Second World War to become (South) Korea’s first president.

But most of those who fled the Japanese found havens in Russian-influenced Manchuria. The best known of these “Eastern” exiles, Kim Il-sung, became an anti-Japanese guerrilla and joined the Communist Party. At the same time Syngman Rhee arrived in the American-controlled South, Kim Il-sung became the leader of the Soviet-supported North. There he founded the ruling “dynasty” of which his grandson Kim Jong-un is the current leader.

During the 35 years of Japanese occupation, no one in the West paid much attention to Syngman Rhee or his hopes for the future of Korea, but the Soviet government was more attentive to Kim Il-Sung. While distant Britain, France and America played no active role, the near-by Soviet Union, with a long frontier with Japanese-held territory, had to concern itself with Korea.

It was not so much from strategy or the perception of danger that Western policy (and Soviet acquiescence to it) evolved. Driven in part by sentiment, America forced a change in the tone of relations with the colonial world during the Second World War and, driven by the need to appease America, Britain and France acquiesced. It was the tide of war, rather than any preconceived plan, that swept Korea into the widely scattered and ill-defined group of “emerging” nations.

As heir to the dreams of Woodrow Wilson, Franklin Roosevelt proclaimed that colonial peoples deserved to be free. Korea was to benefit from the great liberation of the Second World War. So it was that on December 1, 1943, the United States, Britain and (then Nationalist) China agreed at the Cairo Conference to apply the revolutionary words of the 1941 Atlantic Charter: “Mindful of the enslavement of the people of Korea,” Roosevelt and a reluctant Churchill proclaimed, they “are determined that in due course Korea shall become free and independent.”

At the April-June 1945 San Francisco conference, where the United Nations was founded, Korea got little attention, but a vague arrangement was envisaged in which Korea would be put under a four-power (American, British, Chinese and Soviet) trusteeship. This policy was later affirmed at the Potsdam Conference on July 26, 1945, and was agreed to by the Soviet Union on August 8 when it declared war on Japan. Two days later Russian troops fanned out over the northern area. It was not until almost a month later, on September 8, that the first contingents of the U.S. Army arrived.

Aftermath of War

Up to that point, most Koreans could do little to effect their own liberation: those inside Korea were either in prison, lived in terror that they soon would be arrested or collaborated with the Japanese. The few who had reached havens in the West, like Syngman Rhee, found that while they were allowed to speak, no one with the power to help them listened to their voices. They were to be liberated but not helped to liberate themselves. It was only the small groups of Korean exiles in Soviet-controlled areas who actually fought their Japanese tormentors. Thus it was that the Communist-led Korean guerrilla movement began to play a role similar to insurgencies in Indochina, the Philippines and Indonesia.

As they prepared to invade Korea, neither the Americans nor the Russians evinced any notion of the difference between the Puk-in or “people of the North” and the Nam-in or “people of the South.” They were initially concerned, as least in their agreements with one another as they had been in Germany, by the need to prevent the collision of their advancing armed forces. The Japanese, however, treated the two zones that had been created by this ad hoc military decision separately.

As a Soviet army advanced, the Japanese realized that they could not resist, but they destroyed as much of the infrastructure of the north as they could while fleeing to the south. On reaching the south, both the soldiers and the civil servants cooperated at least initially with the incoming American forces. Their divergent actions suited both the Russians and the Americans — the Russians were intent on driving out the Japanese while the Americans were already beginning the process of forgiving them. What happened in this confused period set much of the shape of Korea down to the present day.

The Russians appear to have had a long-range policy toward Korea and the Communist-led insurgent force to implement it, but it was only slowly, and reluctantly, that the Americans developed a coherent plan for “their” Korea and found natives who could implement it. What happened was partly ideological and partly circumstantial. It is useful and perhaps important to emphasize the main points:

The first point is that the initial steps of what became the Cold War had already been taken and were quickly reinforced. Although the Yalta Conference included the agreement that Japan would be forced to surrender to all the allies, not just to the United States and China, President Truman set out a different American policy without consulting Stalin.

Buoyed by the success of the test of the atomic bomb on July 16, 1945, he decided that America would set the terms of the Pacific war unilaterally; Stalin reacted by speeding up his army’s attack on Japanese-held Korea and Manchuria. He was intent on creating “facts on the ground.” Thus it was that the events of July and August 1945 anchored the policies – and the interpretations of the war – of each great power. They shaped today’s Korea.

Arguments ever since have focused on the justifications for the policies of each Power. For many years, Americans have argued that it was the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and 9, not the threat or actuality of the Soviet invasion, that forced the Japanese to surrender.

Spoils of War

In the official American view, it was America that won the war in the Pacific. Island by island from Guadalcanal, American soldiers had marched, sailed and flown toward the final island, Japan. From nearby islands and from aircraft carriers, American planes bombed and burned its cities and factories. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the final blows in a long, painful and costly process.

Truman held that the Russians appeared only after the Japanese were defeated. Thus, he felt justified – and empowered – to act alone on Japan. So when General Douglas MacArthur arranged the ceremony of surrender on September 2, he sidelined the Russians. The procedure took place on an American battleship under an American flag. A decade was to pass before the USSR formally ended its war with Japan.

The second crucial point is what was happening on the peninsula of Korea. There a powerful Russian army was present in the North and an American army was in control of the South. The decisions of Cairo, San Francisco and Potsdam were as far from Korea as the high-flown sentiments of the statesmen were from the realities, dangers and opportunities on the scene. What America and the Soviet Union did on the ground was crucial for an understanding of Korea today.

As the Dutch set about doing in Indonesia, the French were doing in Indochina and the Americans were doing in the Philippines, the American military authorities in their part of Korea pushed aside the nationalist leaders (whom the Japanese had just released from prison) and insisted on retaining all power in their own (military) government. They knew almost nothing about (but were inherently suspicious of) the anti-Japanese Koreans who set themselves up as the “People’s Republic.” On behalf of the U.S., General John Hodge rejected the self-proclaimed national government and declared that the military government was the only authority in the American-controlled zone.

Hodge also announced that the “existing Japanese administration would continue in office temporarily to facilitate the occupation” just as the Dutch in Indonesia continued to use Japanese troops to control the Indonesian public. But the Americans quickly realized how unpopular this arrangement was and by January 1946 they had dismantled the Japanese regime.

In the ensuing chaos dozens of groups with real but often vague differences formed themselves into parties and began to demand a role in Korean affairs. This development alarmed the American military governor. Hodge’s objective, understandably, was order and security. The local politicians appeared unable to offer either, and in those years, the American military government imprisoned tens of thousands of political activists.

Cold War in Vitro

Although not so evident in the public announcements, the Americans were already motivated by fear of the Russians and their actual or possible local sympathizers and Communists. Here again, Korea reminds one of Indochina, the Philippines and Indonesia. Wartime allies became peacetime enemies. At least in vitro, the Cold War had already begun.

At just the right moment, virtually as a deux ex machina, Syngman Rhee appeared on the scene. Reliably and vocally anti-Communist, American-oriented, and, although far out of touch with Korean affairs, ethnically Korean, he was just what the American authorities wanted. He gathered the rightist groups into a virtual government that was to grow into an actual government under the U.S. aegis.

Meanwhile, the Soviet authorities faced no similar political or administrative problems. They had available the prototype of a Korean government. This government-to-become already had a history: thousands of Koreans had fled to Manchuria to escape Japanese rule and, when Japan carried the war to them by forming the puppet state they called Manchukuo in 1932, some of the refugees banded together to launch a guerrilla war. The Communist Party inspired and assumed leadership of this insurgency. Then as all insurgents – from Tito to Ho Chi-minh to Sukarno – did, they proclaimed themselves a government-in-exile.

The Korean group was ready, when the Soviet invasion made it possible, to become the nucleus of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The USSR recognized it as the sole government of (all) Korea in September 1948. And, despite its crude and often brutal method of rule, it acquired a patina of legitimacy by its years of armed struggle against the Japanese.

Both the USSR and the U.S. viewed Korea as their outposts. They first tried to work out a deal to divide authority among themselves. But they admitted failure on December 2, 1945. The Russians appeared to expect the failure and hardly reacted, but the Americans sought the help of the United Nations in formalizing their position in Korea. At their behest, the U.N. formed the “Temporary Commission on Korea.” It was supposed to operate in all of Korea, but the Russians regarded it as an American operation and excluded it from the North. After a laborious campaign, it managed to supervise elections but only in the south, in May 1948.

The elections resulted in the formation on August 15 of a government led by Syngman Rhee. In response, a month later on September 9, the former guerrilla leader, Communist and Soviet ally Kim Il-sung, proclaimed the state of North Korea. Thus, the ad hoc arrangement to prevent the collision of two armies morphed into two states.

The USSR had a long history with Kim Il-sung and the leadership of the North. It had discreetly supported the guerrilla movement in Manchukuo (aka Manchuria) and presumably had vetted the Communist leadership through the purges of the 1930s and closely observed them during the war. The survivors were, by Soviet criteria, reliable men. So it was possible for the Russians to take a low profile in North Korean affairs. Unlike the Americans, they felt able to withdraw their army in 1946. Meanwhile, of course, their attention was focused on the much more massive tide of the revolution in China. Korea must have seemed something of a sideshow.

The position of the United States was different in almost every aspect. First, there was no long-standing, pro-American or ideologically democratic cadre in the South.

The Rise of Rhee

The leading figure, as I have mentioned, was Syngman Rhee. While Kim Il-sung was a dedicated Communist, Rhee was certainly not a believer in democracy. But ideology aside, Rhee was deeply influenced by contacts with Americans. Missionaries saved his eyesight (after smallpox), gave him a basic Western-style education, employed him and converted him to Christianity. Probably also influenced by them, as a young man he had involved himself in protests against Korean backwardness, corruption and failure to resist Japanese colonialism. His activities landed him in prison when he was 22 years of age. After four years of what appears to have been a severe regime, he was released and in 1904 made his way into exile in America.

Remarkably for a young man of no particular distinction – although he was proud of a distant relationship to the Korean royal family – he was at least received if not listened to by President Theodore Roosevelt. Ceremonial or perfunctory meetings with other American leaders followed over the years. The American leaders with whom he met did not consider Korea of much importance and even if they had so considered it, Rhee had nothing to offer them. So I infer that his 40-year wanderings from one university to the next (BA in George Washington University, MA in Harvard and PhD in Princeton) and work in the YMCA and other organizations were a litany of frustrations.

It was America’s entry into the war in 1941 that gave Rhee the opportunity he had long sought: he convinced President Franklin Roosevelt to espouse at least nominally the cause of Korean independence. Roosevelt’s kind words probably would have little effect — as Rhee apparently realized. To give them substance, he worked closely with the OSS (the ancestor of the CIA) and developed contacts with the American military chiefs. Two months after the Japanese surrender in 1945, he was flown back to Korea at the order of General Douglas MacArthur.

Establishing himself in Seoul, he led groups of right-wing Koreans to oppose every attempt at cooperation with the Soviet Union and particularly focused on opposition to the creation of a state of North Korea. For those more familiar with European history, he might be considered to have aspired to the role played in Germany by Konrad Adenauer. To play a similar role, Rhee made himself “America’s man.” But he was not able to do what Adenauer could do in Germany nor could he provide for America: an ideologically controlled society and the makings of a unified state like Kim Il-sung was able to give the Soviet Union. But, backed by the American military government and overtly using democratic forms, Rhee was elected on a suspicious return of 92.3 percent of the vote to be president of the newly proclaimed Republic of Korea.

Rhee’s weakness relative to Kim had two effects: the first was that while Soviet forces could be withdrawn from the North in 1946, America felt unable to withdraw its forces from the South. They have remained ever since. And the second effect was that while Rhee tried to impose upon his society an authoritarian regime, similar to the one imposed on the North, he was unable to do so effectively and at acceptable cost.

The administration he partly inherited was largely dependent upon men who had served the Japanese as soldiers and police. He was tarred with their brush. It put aside the positive call of nationalism for the negative warning of anti-Communism. Instead of leadership, it relied on repression. Indeed, it engaged in a brutal repression, which resembled that of North Korea but which, unlike the North Korean tyranny, was widely publicized. Resentment in South Korea against Rhee and his regime soon grew to the level of a virtual insurgency. Rhee may have been the darling of America but he was unloved in Korea. That was the situation when the Korean War began.

Resumption of War

The Korean War technically began on June 25, 1950, but of course the process began before the first shots were fired. Both Syngman Rhee and Kim Il-sung were determined to reunite Korea, each on his own terms. Rhee had publicly spoken on the “need” to invade the North to reunify the peninsula; the Communist government didn’t need to make public pronouncements, but events on the ground must have convinced Kim Il-sung that the war had already begun. Along the dividing line, according to one American scholar of Korea, Professor John Merrill, large numbers of Koreans had already been wounded or killed before the “war” began.

In this July 1950 U.S. Army file photograph once classified “top secret,” South Korean soldiers walk among some of the thousands of South Korean political prisoners shot at Taejon, South Korea, early in the Korean War. (AP Photo/National Archives, Major Abbott/U.S. Army, File)

The event that appears to have precipitated the full-scale war was the declaration by Syngman Rhee’s government of the independence of the South. If allowed to stand, that action as Kim Il-sung clearly understood, would have prevented unification. He regarded it as an act of war. He was ready for war. He had used his years in power to build one of the largest armies in the world whereas the army of the South had been bled by the Southern rulers.

Kim Il-sung must have known in detail the corruption, disorganization and weakness of Rhee’s administration. As the English journalist and commentator on Korea Max Hastings reported, Rhee’s entourage was engaged in a massive theft of public resources and revenues. Money intended by the foreign donors to build a modern state was siphoned off to foreign bank accounts; “ghost soldiers,” the military equivalent of Gogol’s Dead Souls, who existed only on army records, were paid salaries which the senior officers pocketed while the relatively few actual soldiers went unpaid and even unclothed, unarmed and unfed. Bluntly put, Rhee offered Kim an opportunity he could not refuse.

We now know, but then did not, that Stalin was not in favor of the attack by the North and agreed to it only if China, by then a fellow Communist-led state, took responsibility. What “responsibility” really meant was not clear, but it proved sufficient to tip Kim Il-sung into action. He ordered his army to invade the South. Quickly crossing the demarcation line, his soldiers pushed south. Far better disciplined and motivated, they took Seoul within three days, on June 28.

Syngman Rhee proclaimed a fight to the death but, in fact, he and his inner circle had already fled. They were quickly followed by thousands of soldiers of the Southern army. Many of those who did not flee, defected to the North.

Organized by the United States, the United Nations Security Council – taking advantage of the absence of the Soviet delegation – voted on June 27, just before the fall of Seoul, to create a force to protect the South. Some 21 countries led by the United States furnished about three million soldiers to defend the South. They were countries like Thailand, South Vietnam and Turkey with their own problems of insurgency, but most of the fighting was done by American forces. They were driven south and nearly off the Korean peninsula by Kim Il-sung’s army. The American troops were ill-equipped and nearly always outnumbered. The fighting was bitter and casualties were high. By late August, they held only a tenth of what had been the Republic of Korea, just the southern province around the city of Pusan.

The Chinese Prepare

Wisely analyzing the actual imbalance of the American-backed southern forces and the apparently victorious forces commanded by Kim Il-sung, the Chinese statesman Zhou Enlai ordered his military staff to guess what the Americans could be expected to do: negotiate, withdraw or try to break out of their foothold at Pusan. The staff reported that the Americans would certainly mobilize their superior potential power to counterattack.

Seriously wounded North Korean soldiers lie where they fell and wait for medical attention by Navy hospital corpsmen accompanying the Marines in their advance. September 15, 1950. (Photo by Sgt. Frank Kerr, USMC)

To guard against intrusion into China, Zhou convinced his colleagues to move military forces up to the Chinese-Korean frontier and convinced the Soviet government to give the North Koreans air support. What was remarkable was that Zhou’s staff exactly predicted what the Americans would do and where they would do it. Led by General Douglas MacArthur, the Americans made a skillful and bold counterattack. Landing at Inchon on September 15, they cut the bulk of the Northern army off from their bases. The operation was a brilliant military success.

But, like many brilliant military actions, it developed a life of its own. MacArthur, backed by American Secretary of State Dean Acheson and General George Marshall — and ordered by President Truman — decided to move north to implement Syngman Rhee’s program to unify Korea. Beginning on September 25, American forces recaptured Seoul, virtually destroyed the surrounded North Korean army and on October 1 crossed the 38th parallel. With little to stop them, they then pushed ahead toward the Yalu river on the Chinese frontier. That move frightened both the Soviet and Chinese governments which feared that the wave of victory would carry the American into their territories. Stalin held back, refusing to commit Soviet forces, but he reminded the Chinese of their “responsibility” for Korea.

In response, the Chinese hit on a novel ploy. They sent a huge armed force, some 300,000 men to stop the Americans but, to avoid at least formally and directly a clash with America, they categorized it as an irregular group of volunteers — the “Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.” Beginning on October 25. the lightly armed Chinese virtually annihilated what remained of the South Korean army and drove the Americans out of North Korea.

Astonished by the collapse of what had seemed a definitive victory, President Truman declared a national emergency, and General MacArthur urged the use of 50 nuclear bombs to stop the Chinese. What would have happened then is a matter of speculation, but what did happen was that MacArthur was replaced by General Matthew Ridgeway who restored the balance of conventional forces. Drearily, the war rolled on.

During this period and for the next two years, the American air force carried out massive bombing sorties. Some of the bombing was meant to destroy the Chinese and North Korean ability to keep fighting, but Korea is a small territory and what began as “surgical strikes” grew into carpet-bombing. (Such bombing would be considered a war crime as of the 1977 Protocol I of the Geneva Conventions).

The attacks were enormous. About 635,000 tons of high explosives and chemical weapons were dropped – that was far more than was used against the Japanese in the Second World War. As historian Bruce Cumings has pointed out, the U.S. Air Force found that “three years of ‘rain and ruin’” had inflicted greater damage on Korean cities “than German and Japanese cities firebombed during World War II.” The North Korean capital Pyongyang was razed and General Curtis LeMay thought American bombings caused the deaths of about 20 percent — one in five — North Koreans.

Carpet-Bombing the North

LeMay’s figure, horrifying as it is, needs to be borne in mind today. Start with the probability that it is understated. Canadian economist Michel Chossudovsky has written that LeMay’s estimate of 20 percent should be revised to nearly 33 percent or roughly one Korean in three killed. He goes on to point to a remarkable comparison: in the Second World War, the British had lost less than 1 percent of their population, France lost 1.35 percent, China lost 1.89 percent and the U.S. only a third of 1 percent. Put another way, Korea proportionally suffered roughly 30 times as many people killed in 37 months of American carpet-bombing as these other countries lost in all the years of the Second World War.

In all, 8 million to 9 million Koreans were killed. Whole families were wiped out and practically no families alive in Korea today are without close relatives who perished. Virtually every building in the North was destroyed. What General LeMay said in another context – “bombing them back to the Stone Age” – was literally effected in Korea. The only survivors were those who holed up in caves and tunnels.

Memories of those horrible days, weeks and months of fear, pain and death seared the memories of the survivors, and according to most observers they constitute the underlying mindset of hatred and fear so evident among North Koreans today. They will condition whatever negotiations America attempts with the North.

Finally, after protracted battles on the ground and daily or hourly assaults from the sky, the North Koreans agreed to negotiate a ceasefire. Actually achieving it took two years.

The most significant points in the agreement were that (first) there would be two Koreas divided by a demilitarized zone essentially on what had been the line drawn along the 38th parallel to keep the invading Soviet and American armies from colliding and (second) article 13(d) of the agreement specified that no new weapons other than replacements would be introduced on the peninsula. That meant that all parties agreed not to introduce nuclear and other “advanced” weapons.

What needs to be remembered in order to understand future events is that, in effect, the ceasefire created not two but three Koreas: North, South, and the American military bases.

The North set about recovering from devastation. It had to dig out from under the rubble and it chose to continue to be a garrison state. It was certainly a dictatorship, like the Soviet Union, China, North Vietnam and Indonesia, but close observers thought that the regime was supported by the people. Most observers found that the memory of the war, and particularly of the constant bombing, created a sense of embattlement that unified the country against the Americans and the regime of the South. Kim Il-sung was able to stifle such dissent as arose. He did so brutally. No one can judge for certain, but there is reason to believe that a sense of embattled patriotism remains alive today.

South’s Military Dictatorships

The South was much less harmed by the war than the North and, with large injections of aid and investment from Japan and America, it started on the road to a remarkable prosperity. Perhaps in part because of these two factors – relatively little damage from the war and growing prosperity – its politics was volatile.

To contain it and stay in power, Syngman Rhee’s government imposed martial law, altered the constitution, rigged elections, opened fire on demonstrators and even executed leaders of the opposing party. We rightly deplore the oppression of the North, but humanitarian rights investigations showed little difference between the Communist/Confucian North and the Capitalist/Christian South. Syngman Rhee’s tactics were not less brutal than those of Kim Il-sung.

Employing them, Rhee managed another electoral victory in 1952 and a third in 1960. He won the 1960 election with a favorable vote officially registered to be 90 percent. Not surprisingly, he was accused of fraud. The student organizations regarded his manipulation as the “last straw” and, having no other recourse, took to the streets. Just ahead of a mob converging on his palace — much like the last day of the government of South Vietnam a few years later — he was hustled out of Seoul by the CIA to an exile in Honolulu.

The third Korea, the American “Korea,” would have been only notional except for the facts that it occupied a part of the South (the southern perimeter of the demilitarized zone and various bases elsewhere), had ultimate control of the military forces of the South (it was authorized to take command of them in the event of war) and, as the British had done in Egypt, Iraq and India, it “guided” the native government it had fostered. Its military forces guaranteed the independence of the South and at least initially, the United States paid about half the costs of the government and sustained its economy.

At the same time, the United States sought to weaken the North by imposing embargos. It kept the North on edge by carrying what the North regarded as threatening maneuvers on its frontier and, from time to time, as President Bill Clinton did in 1994 (and President Donald Trump is now doing), threatened a devastating preemptive strike. The Defense Department and the Joint Chiefs of Staff also developed OPLN 5015, one of a succession of secret plans whose intent, in the words of commentator Michael Peck, was “to destroy North Korea.”

And, in light of America’s worry about nuclear weapons in Korea, we have to confront the fact that it was America that introduced them. In June 1957, the U.S. informed the North Koreans that it would no longer abide by Paragraph 13(d) of the armistice agreement that forbade the introduction of new weapons. A few months later, in January 1958, it set up nuclear-tipped missiles capable of reaching Moscow and Peking. The U.S. kept them there until 1991. It wanted to reintroduce them in 2013 but the then South Korean Prime Minister Chung Hong-won refused.

As I will later mention, South Korea joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1975, and North Korea joined in 1985. But South Korea covertly violated it from 1982 to 2000 and North Korea first violated the provisions in 1993 and then withdrew from it in 2003. North Korea conducted its first underground nuclear test in 2006.

There is little moral high ground for any one of the “three Koreas.”

New elections were held in the South and what was known as the Second Republic was created in 1960 under what had been the opposition party. It let loose the pent-up anger over the tyranny and corruption of Syngman Rhee’s government and moved to purge the army and security forces. Some 4,000 men lost their jobs and many were indicted for crimes. Fearing for their jobs and their lives, they found a savior in General Park Chung-hee who led the military to a coup d’état on May 16, 1961.

General Park was best known for having fought the guerrillas led by Kim Il-sung as an officer in the Japanese “pacification force” in Manchukuo. During that period of his life, he even replaced his Korean name with a Japanese name. As president, he courted Japan. Restoring diplomatic relations, he also promoted the massive Japanese investment that jump-started Korean economic development. With America he was even more forthcoming. In return for aid, and possibly because of his close involvement with the American military – he studied at the Command and General Staff school at Fort Sill – he sent a quarter of a million South Korean troops to fight under American command in Vietnam.

Not less oppressive than Rhee’s government, Park’s government was a dictatorship. To protect his rule, he replaced civilian officials by military officers. Additionally, he formed a secret government within the formal government; known as the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, it operated like the Gestapo. It routinely arrested, imprisoned and tortured Koreans suspected of opposition. And, in October 1972, Park rewrote the constitution to give himself virtual perpetual power. He remained in office for 16 years. In response to oppression and despite the atmosphere of fear, large-scale protests broke out against his rule. It was not, however, a public uprising that ended his rule: his chief of intelligence assassinated him in 1979.

An attempt to return to civilian rule was blocked within a week by a new military coup d’état. The protests that followed were quickly put down and thousands more were arrested. A confused scramble for power then ensued out of which in 1987 a Sixth Republic was announced and one of the members of the previous military junta became president.

The new president Roh Tae-woo undertook a policy of conciliation with the North and under the warming of relations both North and South joined the U.N. in September 1991. They also agreed to denuclearization of the peninsula. But, as often happens, the easing of suppressive rule caused the “reformer” to fall. Roh and another former president were arrested, tried and sentenced to prison for a variety of crimes — but not for their role in anti-democratic politics. Koreans remained little motivated by more than the overt forms of democracy.

Relations between the North and the South over the next few years bounced from finger on the trigger to hand outstretched. The final attempt to bring order to the South came when Park Geun-hye was elected in 2013, She was the daughter of General Park Chung-hee who, as we have seen, had seized power in a coup d’état 1963 and was president of South Korea for 16 years. Park Geun-hye, was the first women to become head of a state in east Asia. A true daughter of her father, she ruled with an iron hand, but like other members of the ruling group, she far overplayed her hand and was convicted of malfeasance and forced out of office in March 2017.

The Kim Dynasty

Meanwhile in the North, as Communist Party head, Prime Minister from 1948 to 1972 and president from 1972 to his death in 1994, Kim Il-sung ruled North Korea for nearly half a century. His policy for his nation was a sort of throw-back to the ancient Korean ideal of isolation. Known as juche, it emphasized self-reliance. The North was essentially an agrarian society and, unlike the South, which from the 1980s welcomed foreign investment and aid, it remained closed. Initially, this policy worked well: up to the end of the 1970s, North Korea was relatively richer than the South, but then the South raced ahead with what amounted to an industrial revolution.

Surprisingly, Kim Il-sung shared with Syngman Rhee a Protestant Christian youth; indeed, Kim said that his grandfather was a Presbyterian minister. But the more important influence on his life was the brutal Japanese occupation. Such information as we have is shaped by official pronouncements and amount to a paean. But, probably, like many of the Asian nationalists, as a very young man he took part in demonstrations against the occupying power. According to the official account, by the time he was 17, he had spent time in a Japanese prison.

At 19, in 1931, he joined the Chinese Communist Party and a few years later became a member of its Manchurian fighting group. Hunted down by the Japanese and such of their Korean collaborators as Park Chung-hee, Kim crossed into Russian territory and was inducted into the Soviet army in which he served until the end of the Second World War. Then, as the Americans did with Syngman Rhee, the Russians installed him as head of the provisional government.

From the first days of his coming to power, Kim Il-sung focused on the acquisition of military power. Understandably from his own experience, he emphasized training it in informal tactics, but as the Soviet Union began to provide heavy equipment, he pushed his officers into conventional military training under Russian drillmasters. By the time he had decided to invade South Korea, the army was massive, armed on a European standard and well organized. Almost every adult Korean man was or had been serving in it.

The army had virtually become the state. This allocation of resources, as the Korean War made clear, resulted in a powerful striking force but a weakened economy. It also caused Kim’s Chinese supporters to decide to push him aside. How he survived his temporary demotion is not known, but in the aftermath of the ceasefire, he was again seen to be firmly in control of the Communist Party and the North Korean state.

The North Korean state, as we have seen, had virtually ceased to exist under the bombing attack. Kim could hope for little help to rebuild it from abroad and sought even less. His policy of self-reliance and militarization were imposed on the country. On the Soviet model of the 1930s, he launched a draconian five-year plan in which virtually all economic resources were nationalized. In the much-publicized Sino-Soviet split, he first sided with the Chinese but, disturbed by the Chinese Cultural Revolution, he swung back to closer relations with the Soviet Union.

In effect, the two neighboring powers had to be his poles. His policy of independence was influential but could not be decisive. To underpin his rule and presumably in part to build the sense of independence of his people, he developed an elaborate personality cult. That propaganda cult survived him. When he died in 1994 at 82 years of age, his body was preserved in a glass case where it became the object of something like a pilgrimage.

Unusual for a Communist regime, Kim Il-sung was followed by his son Kim Jong-Il. Kim Jong-Il continued most of his father’s policies, which toward the end of his life, had moved haltingly toward a partial accommodation with South Korea and the United States. He was faced with a devastating drought in 2001 and sequential famine that was said to have starved some 3 million people. Perhaps seeking to disguise the impact of this famine, he abrogated the armistice and sent troops into the demilitarized zone. However, intermittent moves including creating a partly extra-territorialized industrial enclave for foreign trade, were made to better relations with the South.

Then, in January 2002, President George Bush made his “Axis of Evil Speech” in which he demonized North Korea. Thereafter, North Korea withdrew from the 1992 agreement with the South to ban nuclear weapons and announced that it had enough weapons-grade plutonium to make about 5 or 6 nuclear weapons. Although he was probably incapacitated by a stroke in August 2008, his condition was hidden as long as possible while preparations were made for succession. He died in December 2011 and was followed by his son Kim Jong-un.

With this thumbnail sketch of events up to the coming to power of Kim Jong-un and Donald Trump, I will turn in Part 2 of this essay to the dangerous situation in which our governments – and all of us individually – find ourselves today.

William R. Polk is a veteran foreign policy consultant, author and professor who taught Middle Eastern studies at Harvard. President John F. Kennedy appointed Polk to the State Department’s Policy Planning Council where he served during the Cuban Missile Crisis. His books include: Violent Politics: Insurgency and Terrorism; Understanding Iraq; Understanding Iran; Personal History: Living in Interesting Times; Distant Thunder: Reflections on the Dangers of Our Times; and Humpty Dumpty: The Fate of Regime Change.

Thank you very much for this most informative piece.

All this history falls into the category of “true but irrelevant”. North Korea only has to look at recent American atrocities in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya to know that the only way to avoid being invaded by the US is to have a nuclear deterrent.

Very interesting

What interest has USA in Korea? Is it oil Iron ? So much deaths and for what does America get in return?

I also wonder what interests America has in initiating another war

Mineral resources in north Korea could be part of the explanation.

https://qz.com/1004330/north-korea-is-sitting-on-trillions-of-dollars-on-untapped-wealth-and-its-neighbors-want-a-piece-of-it/

However the strategic importance of the Korean peninsula is probably enough motivation. The question, however, is what options remain for the U.S. president if he keeps insisting that the era of “strategic patience” is over.

http://www.zoominkorea.org/north-koreas-deterrent-and-trumps-options/

https://www.counterpunch.org/2017/08/25/why-cant-wheeler-dealer-trump-cut-a-deal-with-north-korea/

This article by William R. Polk is an important piece of history to understand Korea of today. His account is interesting, but it has some weaknesses, which I pointed out when recommending it to Facebook readers. With great respect, I would like to share them here for discussion.

1. The allegation that Korean society, although nominally unified as one kingdom, was in reality split between the Puk-in or “the people in the north” and the Nam-in or “the people in the south” is to my understanding an anachronistic reconstruction of facts, motivating and excusing the tragic division of the country in 1945, which was a result not of internal contradictions, but of U.S. intervention. Certainly there were regional differences as well as class contradictions in the old Korean society, but during the more than 1,000 years that Korea was united as one kingdom, north-south division was not a prominent feature.

2. [As pointed out here by David A Hart,] the Taft-Katsura discussion in 1905 (which secured US control over the Philippines and gave Japan free hands in Korea) is important in this context, as is the Second International Peace Conference in The Hague, which could be compared to today’s biased UN Security Council.

3. The claim that “it was the tide of war, rather than a predetermined plan, which swept Korea into the vast and undefined group of ‘emerging’ nations” tends to disregard the long, laborious and ultimately successful national liberation struggle against Japanese colonialism (and against its successor US imperialism).

4. It is true that it was not until almost a month after the start of the Russian offensive that the first contingents of the U.S. army arrived in Korea, but what is not made clear in the article is that this was three weeks after Korea was liberated, i.e. in a situation when Japan had surrendered and the Koreans themselves were in the process of organizing their new state power.

5. “Up to that point, the majority of Koreans could do little to effect their own liberation” is an assertion that neglects the resistance struggle and the organization of peoples committees all over the country and the fact that the U.S. troops in south Korea actively crushed these attempts, establishing a brutal military regime. Correct, however, is the statement that “the Russians were intent on driving out the Japanese while the Americans were already beginning the process of forgiving them” – though it was not really “the Russians”, but the Soviet Union and the Korean liberation movement in collaboration.

6. The description of the resistance movement, the Communist Party and the exile government is incorrect. The Korean Communist Party had been dissolved and did not exist as a party. The exile government (in Shanghai) was dominated by bourgeois nationalists, not by communists. The armed resistance and the Association for the Restauration of the Motherland, headed by Kim Il Sung, never proclaimed an exile government, although they prepared to head the establishment of a broadly based independent democratic Korean state.

7. The article mentions the elections in the south in May 1948 (but not the circumstances under which they were carried out), while it does not mention that “the state of North Korea” (i.e. the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea), proclaimed by Kim Il Sung, was also based on elections, carried out – as far as was possible – throughout the country, both north and south.

8. The description of Syngman Rhee is informative, but circumvents the leading role of the U.S. military regime in the military and political formation of the “Republic of Korea” (see for instance Hugh Deane, The Korean War 1945-1953, San Francisco, 1999). The allegations “Rhee tried to impose upon his society an authoritarian regime, similar to the one imposed on the North” and “a brutal repression, which resembled that of North Korea” disregards the fundamental difference between the class bases of the two states, even though the article does note the South Korean regime’s dependence upon “men who had served the Japanese as soldiers and police”. That its power was based on large land and capital owners, the very strata that, like “pro-Japanese elements”, were suppressed in the north, is a fundamental difference, which should not be neglected as explanation of later developments.

9. The Korean losses during the Korean War are compared to the World War II losses of Britain, France, China and the United States. However, the Soviet Union, which accounted for most of the fighting against Hitler Germany and suffered incomparably greatest losses, is not mentioned at all – a significant omission.

10. “The third Korea”, the US bases, was not a result of the ceasefire agreement (nor was the formal recognition of “two Koreas”). On the contrary, the agreement provided for the withdrawal of all foreign troops and forthcoming negotiations on a peace agreement.

11. A remarkable void in the account for Korea’s post-war history is the omission of developments in the 1990s, Kim Dae Jung and his Sunshine Politics, the North-South Joint Statements and the 2000-2008 period of relaxation. (They are hidden in the sentence “Relations between the North and the South over the next few years bounced from the finger on the trigger to hand outstretched.”)

12. This said, the article contains many important points and I much look forward to Part 2 of this essay, which will deal with the situation today.

excellent overview that every American should read and consider before they jump to conclusions of any sort.

Thanx for the informative article. But I can’t find the evidence for the claim that up to 33 percent of the population was killed. Could some help me out here?

Thanks to CN for this historical essay, and I look forward to Part 2. This shows how desperately Americans need to learn their history and involvement with other nations, uncensored and unfiltered by the military-industrial-corporate complex. Donald Trump and his military masters are only making things worse through his bluster. It seems that diplomacy has been abandoned by the USA completely. I doubt that Donald Trump could make it through this essay.

William R. Polk’s “thumbnail sketch” is up to his usual standard for presentation of the essential elements of the historical continuities he outlines. In this case he presents from American Standard History source, providing startling information for presenting more of the detail, without glossing away the “unpleasant”, or “unpatriotic”, to “smooth” the ambiance of the narration.

His reliance on the American Standard is revealed in omissions the omissions incorporate in that standard impart. Readers who have read C.P.Snow and other deprecated correspondents and have searched into the “forbidden” literatures of Asia, to learn more of glossed background, the ‘division’ of the world, between Portuguese and Spanish, by a Pope, for instance, and the “opening” of Asia by Europeans, for colonial exploitation with firearms and commercial-purpose religion (both of which Mr. Plk touches on, but pases over), and with gunboats and opium, followed by “expeditionary forces”, meaning booty-seeking privateer armies, which he does not mention, doing vanguard for looters and extortionists (doing business as “missionaries”, which he does touch on), and the colonialist bias that up into and through the FDR era (his family fortune was in substantial part from China-trade/exploitation) favoring a colonial-overseer form of government, to such extent a much larger, and popular (in China) China was deprecated and then “disappeared”, will notice the absence of that officially “disappeared” China in Mr. Polk’s thumbnail.

In American Standard Asian history dealings during WWII and after were with Chang Kai-Shek or “Europeans” (except unofficially in the war when some ‘leakage’ of support went to the Mao forces, who were, ‘somehow’ effective, while the “Nationalist” army, who did not get most of what was provided for them, were not). The “Europeans”, after the war were the “Russians”, wherefore when the mass of China broke from Chang and became independent it, in American Standard History ‘fell off the Earth’ and disappeared. The “Russians” (Soviets), being Europeans were “responsible”, having “supported” the breaking off, and made the disappeared “China” a “Soviet Puppet State”, although that “puppet” state, if it had existed, would have had a mind of its own and an entirely different from Soviet model of “Communism”.

For this, in Mr. Polk’s history there is no religious assaulting against Asian cultures, no naval bombardments of civilian cities, no wanton murder of civilian Chinese, no compelled trade, no compulsory permission of drug-trade, no destruction of Chinese culture and literature, thrown down and burnt in looting for salable artifacts, no ‘indemnities’ demands, payable by “right to steal” anything salable and tradable, and no organized opposition to European colonialism and favored puppet governments (except ‘bandits’) and Stalin “turned the country communist” (whereupon it disappeared from the Earth). And, from that, it was Stalin’s Soviet Russia the U.S.(and its wholly owned U.N.) had to deal with behind North Korea.

For this there was no Chinese example of “throwing off the Western Yoke” in 1947, and, as Mr. Polk notes, China did not appear in the United States’ Korean Peninsula colonial war until Stalin ‘directed’ the Chinese to ‘take responsibility’ and the Chinese (who were then not really the Chinese) launched their offensive (out of nowhere, obviously, since their nation did not exist) that threw the U.S. invaders back to almost off the Peninsula.

The Chinese example of throwing off the Western yoke, managed by Mao, was, to East Asians, signal inspiration, a successful Asian assertion of Right to Asia after a century of armament imposed foreign colonial rule. North Korea, next to the disappeared China and inspired by Mao’s accomplishments, both in fighting against the Japanese invasion and attempt to make a Western-style Asian-controlled Asian Colonial Empire (an unsuccessful attempt to throw off the European colonial yoke), was the second Asian culture to successfully (with ‘Non-China’s’ help).

This is additional background that has been instrumental in the formation of North Korean (actually of all Asian as well) perspective of the “West”. The United States’ effort to subdue the ‘locals’ with “total destruction” (next after “total war”), in the early 1950s, using ‘carpet bombing’ was, to Asians, the next escalation after ‘gunboat diplomacy’; more destruction of civil structure and civilians by Western powers with new technical destructive capabilities.

Mr. Polk describes North Korea as a “garrison state”. This is accurate to an extent, but not entirely, since Israel, for example, is also a garrison state. Israel is, however, an outpost garrison state, an aggressive intrusion into as yet unconquered territory. North Korea is a defensive garrison state. Backed into the top of a peninsula North Korea shows a bristle of defensive weaponry against known and demonstrated attackers. The difference is significant, and will be useful to remember and keep in mind when we read Mr. Polk’s follow-up exposition viewing the positions of North Korea and its aggressive opponents in our current situation.

Good perspective on “American Standard” history. For Korea, the US standard history starts with an unprovoked invasion by NK, and omits the carpet-bombing of KN after the war. That is the only account available in mass media and at many libraries, all discordant notes having been purged. So it is very instructive to many in the US to hear of the US complicity in causing the war, its war crimes, and its government-altered history.

A footnote regarding my reference to “the ‘division’ of the world, between Portuguese and Spanish, by a Pope”, for those not familiar with it: In 1452 and 1493 Papal Bulls were issued, the first declaring all “non-Christian” lands subject to conquest, the second specifically “granting” Spain “possession” of all “non-Christan” lands west of a demarcation line (Portugal got east of the line, which meant Brazil, which, in 1493 was not known to stick out east of the line designated). “Christian” in the Bulls meant Roman Christian. Protestant Christians did not, of course, recognize papal authority. For this they rejected, accepted and rejected the Papal Doctrine of the Bulls (which has become known as “The Doctrine of Discovery”): They first rejected the Bulls’ Doctrine for their being Papal, then accepted them for “practical purposes”, acknowledging them doctrine, and then rejected them again for their dividing all unknown lands between “Catholic” countries, By this acceptance and rejection the Protestant nations, e.g., the British and Dutch, could “take” “discovered lands” lands from the Spanish and the Portuguese for those nations having no real rights to them, only Papal mumbo-jumbo. The effect has been for lands owned by non-Europeans to be divided among Europeans as if the peoples on the lands were not on them and had no rights of their own to their own lands, or to be on them. The non-law of the Papal decrees has been translated into “laws” and used as “precedent” for laws that have been used to disenfranchise persons outside of the populations making the laws and using them, the “laws” assigning indigenous peoples and inhabitants to either not exist, exist as non-humans, or be “fauna”, varmint, game, ‘domesticatable’, plunderable or eradicable, as the “owners under Doctrine” might choose.

Thus, even before the mainland nation of China was made to cease to exist, in the mid 20th century (until “discovered” by Richard Nixon) its people and culture did not exist as people and culture, except as indigenous possessions that came with the land, and the carpet-bombing of North Koreans was (is still, “law” “recognizing” the Doctrine being still in effect) equatable, under the “law” with, for example, Australians eradicating rabbits, or dingos, or North Americans slaughtering bison.

Evangelista, these observations are useful to many readers. The extremity of depersonalization of the native peoples was codified for colonizing Spain and Portugal by a 16th-century decision by religious authorities that they had no “souls” unless converted to Christianity. That proves the failure of those religions in moral education: they had become political instruments, which define “morality” in terms of conformity and power rather than sympathy. They have some defense in the great ignorance of that time, but of course the religions enforced that ignorance.

I would not attribute the US carpet-bombing of NK to an accepted doctrine of dehumanization, although there was little sympathy with those of distinct cultures. The US military, politicians, mass media, and right-wing were angry that they had been defeated with great losses, and publicly embarrassed. Just as their policy had been based upon ignorance, selfishness, hypocrisy, and malice, so was their reaction: they would hit back with whatever they had, and refuse to examine the causes, the interests of others, the persons injured versus those they opposed, etc. Little has changed among warmongers, the greatest threat to democracy.

But you are right that the West has accepted anti-human values with its unregulated market economies, accepting wealth as virtue no matter how it is got, and accepting that power confers the right to abuse power. It is an anti-moral culture of selfishness, dominated since WWI by the selfish oligarchy of money, WallSt, MIC, and zionism, who control mass media and elections.

Just noting your repeated elevation of zionism to the status of a Great Power. I think you’re oversimplifying it and also overexaggerating it beyond any legitimate usage. I also think you’re likely a bigot, although an otherwise intelligent one.

This four-minute video shows the Mass Games held in North Korea, as seen through the eyes of two Canadian travel guys. You can see the pride in the North Korean people. These guys said that North Korea is really one of the last places on Earth where you can find an intact culture. Maybe that could be considered one “advantage” of being isolated? You don’t end up with 7-11’s, McDonald’s and American banks on every corner.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uqrg0dO99yE

I saw the Mass Games in Pyongyang in 2011, and was blown away. It was an unbelievable and impressive display and presentation of the history of Korea from the colonization by Japan up to the present time. The singing, dancing, gymnastics and card section display were phenomenal, and I was also very impressed by the quiet pride and confidence of the North Korean people.

Wow. I am now a PhD candidate if I can pass my orals, if that is the way they do it. I am amazed at the quality of the writers Mr. Parry draws to the site.

Once again, our exceptionalism is tainted by our actions. Genocide. Whatever else could you call it.

‘It was to China rather than to America that Koreans turned for protection against the Japanese “rising sun.”’

That was because they knew that the Japanese were US proxies – just as ISIS are today.

Tom Welsh – “The Japanese were US proxies – just as ISIS are today.” History shows this time and time again. When you read articles like this, keeping in mind how the U.S. operates, you can just picture the wheels turning.

I look forward to Part 2 of this mini-education drill.

Not a single mention of the Mungyeong Massacre in December of 1949, where suspected communists many of them children, were killed on orders from Rhee, then blamed on North Korean raids. Provocations such as these from the South is what led the North to attack. Rhee spent his adult life in the US, whatever he did in South Korea leading up to the war, including the extermination of the Bodo League (a purge of several hundred thousand communist sympathizers in the South, who were identified, put into camps, and finally exterminated) in June and July of 1950, was under orders from Washington.

Washington was, is, and will continue to be the driving force behind the war, not Pyongyang or Seoul.

Common Tater – thanks for filling in the gaps. History books are riddled with “gaps”.

Right back at you backwardevolution … I get many good leads and links from the commentary on this site.

“So why do they hate us” ?

I feel sure that 95% of the US Public is completely unaware of the monstrous destruction carried out by the “Pentagon” on behalf of the American People.

The cost to US taxpayers must have been enormous but unpublicized & a state of “war” has existed ever since.

In the ” Intercept” May 3, 2017. General Curtis LeMay, who directed the strategic bombing of both Japan and Korea, offered this observation we “killed off…20 percent of the population…We went over there and fought the war and eventually burned down every town in North Korea.”

http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/47008.htm

Eight to nine million Koreans were killed a fact you will never read in the MSM in the west

And all the blame is put on Kim Il-sung for his “recklessness” in leading North Korea into war.

Informative but flawed by insufficient economic analysis – early industrialization in the DPRK, the tipping point when chaebols dominated politics in the south, etc. More economic analysis it would, among other benefits, explain some of the changes in strength and political supremacy that pop up in this essay like dei ex machina.

On that “Three Koreas” issue: North, South, American bases. When did the U.N. and the Blue Flag drop out of the picture? Why are the American Bases not U.N. Bases? Whenever the U. N. dropped out is when the U.S. military should also have withdrawn, as the Korean War was a U.N. operation against North Korea’s invasion of South Korea. This part of the story seems vague to me. Can anyone clarify what happened to U.N. participation? It seems wrong to me, for American Forces to be there without the Blue Flag and Blue Helmets being there. WHEN did this become an exclusive American-South Korean arrangement, what year?

The UN had just formed and was dominated by the US (also causing the tragic error of forming Israel). It apparently had no substantial budget or experience of large operations. The UN resolution was apparently taken as non-binding or advisory.

“the U.N. formed the ‘Temporary Commission on Korea’ …the Russians regarded it as an American operation and excluded it from the North. …it managed to supervise elections but only in the south, in May 1948.”

It was in fact vague participation, and the US influence at the UN, and apparent unwillingness to hand over power or negotiate seriously with Stalin may have been a factor in his rejection of the UN election, and the US decision to proceed alone.

Also, Korea was considered a very minor nuisance by the US when everyone went home after the war, so that the US military government was understaffed and reluctant to be there. It found the extreme poverty of the vast majority to be unpleasant and could talk only with the relatively wealthy South Koreans, who had been the comprador class under the Japanese. So the US accidentally did all the wrong things under the circumstances, for lack of local knowledge and concern beyond vague principles.

I can’t help but think this would all have been handled differently had FDR been alive, or, as Joe said, Henry Wallace was the veep. Basically it was de-colonizing a part of the Japanese Empire called Korea. This was FDRs agenda, to liberate and develop former colonies, turning them into sovereign Republics,to become UN members. The problem was Truman fell completely into,the orbit of Churchill, which meant, City-of-London/Wall Street, which meant the Dulles brothers and the ratlines and the subversion of our intelligence community away from FDR, his OSS guys and their 1940 findings on the Synarchy Movement. FDR knew Churchill was also a problem for the World, but less virulent than was Hitler and Mussolini and Tojo, but he and the French stood against de-colonization, of standing down Empire, what FDR wanted to happen. Truman instead fell for anti communism, dropping anti-Empirism and all the implications of the Intel on Synarchy, which to the very thing which happened, a fascistic corporate Empirism spread across three quarters of the World. FDR and Henry Wallace would not have stood for this, and Synarchy was very weak at this point in history. Gen MacArthur and Eisenhower both advised JFK not to get involved in a war on the Asian landmass. Korea and Vietnam were “a bridge too far” in their 1961 opinions. This is all moot now, since China has left behind its “Gang of Four, Red Guards” crazy phase and embraced their Confucian soul. That and Russia’s turning away from the Communist Party makes this an era for FDRs grand vision for World peace to finally triumph.

Of course, we have to somehow turn our country away from Empirism, turning back to a Constitutional Republic and UN member…tall order.

FDR seems to have had a far better vision than his successors, and none of them had enough knowledge or concern for the world beyond the West to have a global foreign policy.

WWII seems to have disrupted progressivism in the US, creating such a chaos that us/them became the only principle, leading to the Cold War and internal fearmongering. Yet we put the UN framework in place, only to dominate the Security Council and fail to negotiate solutions or respect treaties, as in abrogating the Geneva Accords in Vietnam. In the US the tyrant warmonger faction, always the greatest threat to democracy, was empowered by WWII and nuclear risks to dominate democracy, and has stayed in power by starting endless wars of choice on false pretenses.

Yes, since 1991 “FDRs grand vision for World peace” should have triumphed. The MIC has therefore allied with the zionists in control of US mass media to create a new endless war in the Mideast, and so stay in power by fearmongering, the ancient method of tyrants. Their insane self-contradictory Mideast wars, simultaneously supporting terrorists while claiming to be fighting them, and their efforts in Ukraine and Korea to provoke a new cold war are obviously self-serving and murderous, intended solely to destroy democracy in the US for personal gain. These are extreme acts of treason against the United States, by the zionists and MIC, the US oligarchy.

Hi Brad, Wikipedia has a good article regarding your question wherein this is cited:

“In 1994, UN Secretary General Boutros Boutros-Ghali wrote in a letter to the North Korean Foreign Minister that:

‘the Security Council did not establish the unified command as a subsidiary organ under its control, but merely recommended the creation of such a command, specifying that it be under the authority of the United States. Therefore the dissolution of the unified command does not fall within the responsibility of any United Nations organ but is a matter within the competence of the Government of the United States’.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Nations_Command

This is an excellent summary of modern history of the Koreas, especially in showing the complex misunderstandings and assumptions underlying the division, without apparent pretense or bias. One can only sympathize with both sides and wish that the US and USSR had better understanding and cooperation at that time.

Clearly the path forward is broad discussions and cooperation between NK & SK and Russia, China, and the US.

There is no real obstacle but the intransigence of narrow ideologies and interests of politicians and officials. The NK threats and militarism are solely the product of US & SK provocations and militarism, which in turn are based upon NK’s responses. Eliminate the risks and threats under a UN-supervised mutual-defense plan, and both have only time and healing between their present state and reunification.

Reunification requires a compromise of the forms of economy, which is quite practical. China has done this and provides a supportive model. I told a group of engineers from China in the early 80s that a market economy is a powerful fuel like gasoline, which needs an engine to make it useful: the US throws it around and burns out its economy every ten years, but they could build the engine to harness it. They did that.

Similarly a compromise of the forms of government is quite practical. The NK population (25 million) is only a third of the combined populations, but they can have regional autonomy with state’s rights, and their communist party can be a party under a unification government.

What is needed are assurances in the new government structure, that factions cannot dominate, that economic power does not control mass media or elections, that foreign influence is strictly excluded, and that individual rights are protected.

The US, China, and Russia must agree to make Korea a model of democracy without corruption by economic power or foreign influence. That model would be a valuable experiment, learning experience and model for the greater powers as well, which the new Korea could provide us.

That’s one of the best comments I’ve seen on this thread, Sam. Reunification of the two Korean states does, indeed, require a compromise of the forms of economy, which is quite practical. You’re also spot on by saying that similarly, a compromise of the forms of gov’t. are also practical. The DPRK population (25 million) is only a third of the combined populations; however, they can have regional autonomy with state’s rights, and their communist party can be a party under a unification gov’t.

I also agree that what’s needed are assurances in the new gov’t. structure, that factions cannot dominate, that economic power doesn’t control mass media or elections, that foreign influence is strictly excluded, and that individual rights are protected.

The US, China and Russia must agree to make Korea a model of democracy without corruption by economic power or foreign influence. That model would certainly be a valuable experiment, learning experience and model for the greater powers as well, which the new Korea would provide us all.

An impressive synopsis.

…and lest we forget the mysterious circumstances surrounding the downing of KE007

https://crivellistreetchronicle.blogspot.com/2017/03/kal007-coincidence-or-conspiracy.html

Well while reading this I made up my mind too what I’d do if I were to have a time machine. Without hesitation I would travel in time back to the 1944 Democratic Convention, and do everything in my power to prevent Harry Truman from getting the Vice Presidential spot on the FDR ticket. Between Hiroshima & Nagasaki, the CIA, Vietnam backing the French, as with his recognizing Israel as a state, and now reading this about Truman’s decisions in Korea, leaves me no choice but to declare the Truman presidency the worst of the worst of U.S. Presidents to have ever held the office in the final half of the 20th century.

That’s saying a lot when you consider to how much I abhor LBJ, Nixon, Clinton, the Bush’s, and I probably left out somebody, but still passing up all of those that I mentioned doesn’t speak well for my love of Truman, or better put my lack of love for the guy.

Also, I love reading William R Polk articles. I learn a lot every time he submits one for our enjoyment to read. So, Robert Parry please post more of what this great man has to share with us. Thanks Joe

What a mess! Any honest close up look at human history reveals a horrific tale of greed and violence, with a total absence of anything like conscience or higher values. As Stephen Dedalus, James Joyce’s character in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man said, “History is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake.” The final result of this awful history is now rapidly unfolding.

You are right, as you usually are mike. Yes, we didn’t just get here to this place overnight.

I recall back in 1972 a friend of my dad who was retiring warned that with each corporate buyout that the competition field would lessen. This old news junkie who worked in sales, told me how the real problem would become a huge corporate monopoly, but he went on to say how it would really be an oligarchy disguised as a free enterprise system. This salesman who sold in his industry starting after WWII said how his industry once had had 500 manufacturers, but by the time I (who was 22 at the time) would retire this industry the old salesman referred to would by then only have 5 manufacturers. Old Dave passed on before seeing his prediction come to life, but he was right to the exact number, by the time I hit retirement age Dave’s onetime industry had only 5 super big manufacturing companies. Oh, and all of their many product lines are now offshored.

Sorry, for the story, but I feel it’s just one way to describe the slow but steady decline. Joe

Joe,

You might want to look for a book titled “The Chain Gang”, by Richard McCord. It details ‘How It is Done’, the consolidating of industries. In McCord’s story the victim industry was the newspaper industry, the ‘consolidator’ Gannett, but the methods, coming in with ‘Big Money’ backing, from some source of deep-pocketed backers (usually ‘laundered’, or ‘covered’ by “Wall Street” backing, since just about any money moving and manipulating can be masked and made to look “acceptable” by ‘stock market investing’ cover, with massive financings and losses “transferred” to, or “absorbed” by defined but not identified “investors” and “financiers” [review the Amazon operations methods, where, if you add up the actual numbers over the years the outfit is still way under water]). The technique is to, with the “elsewhere markets income” “available” to spend in the local markets, undercut the local market dependent competition until they can’t, not having outside source additional income, continue taking the losses the local competing costs them and have to fold or sell out.

“The Chain Gang” is also timely today, as it is about information media consolidation and illustrates how the United States’ independent regional media voices were silenced so that a few controlling “media voices” under control of a co-conspiring few (Gannett, Murdoch, Time-Warner) Global-Commercialist investor-owners could direct information dispersal to provide us what we have today, propaganda on their party-line.

Boy Joe, do I ever totally agree. It is wonderful to see another article by William R. Polk here. A gentleman and Scholar, that is all too rare in the media today. Thank you Mr. Polk and to CN for presenting This elucidating essay.

Joe, in my mind I’ve created an image that I cherish that looks like this: Henry Wallace and Eleanor are meeting with the FDR’s New Dealers and organizing policy that would put the People first. It was the humane aspect of FDR’s Administration, the best part, and probably the last time, in American Policy, when the Common Interest was represented by Government.

I like to say that the Truth Jumps off the page and this piece Jumps!

What you mention involving Eleanor is a hidden history painfully missed. In the case of Harry over Henry, it’s plain to see the military industrialists won big. Colonization should be outlawed. Yeah, this history of the early post WWII period should be made more known, because it is a period where many options were available, and it’s clear to now look back and without a doubt recognize to who the buggers are who ended up in control, and regretfully realize what we as a nation loss a lot when losing Wallace, under the Influencers who put Harry in charge. Bob, this has been our whole life. Wow! Joe

Our whole life; a generation. JFK’s “New Fronteer” lost…

Bob, look at the glass as it being half full, because possibly the New Frontier helped add buoyancy to this listing nation we call home. Joe