Donald Trump’s unilateral decision to attack Syria under a preposterous claim of protecting a “vital national security interest” of the U.S. was another case of a President violating the U.S. Constitution, as Daniel C. Maguire explains.

By Daniel C. Maguire

I am old enough to remember the last time the United States declared war in accord with Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. The date was Dec. 8, 1941, and I was ten-years-old. I remember hearing on the radio all the Yay votes and I was jarred to hear one female vote saying Nay. That was Rep. Jeannette Rankin of Montana.

Donald Trump speaking with the media at a hangar at Mesa Gateway Airport in Mesa, Arizona. December 16, 2015. (Flickr Gage Skidmore)

War, by definition, is state sponsored violence. It kills people and animals and savages the natural environment. It is “development” in full reverse, a dreadfully serious undertaking, a power that kings once wielded arbitrarily on their own impulse and authority. But the Founders would have none of that.

So, the U.S. Constitution gave the war power to the Congress, “the immediate representatives of the people.” Congress also received the crucial power of the purse to continue or discontinue war after it starts.

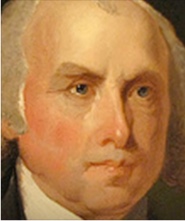

James Madison, the Constitution’s principal architect, wrote: “In no part of the Constitution is more wisdom to be found than in the clause which confides the question of war and peace to the legislature and not to the executive department.”

Yet, in recent decades, the United States has repeatedly trashed that wisdom and done so as recently as April 6, 2017, as President Trump displayed his bully virility and his need to use kill-power to bolster his sagging ratings.

As military analyst Robert Previdi writes: “We have distorted the Constitution by allowing all Presidents since Harry S. Truman to use military power on their own authority. … For more than 160 years, from Washington to Roosevelt, no President claimed that he had the power to move the country from peace to war without first getting authority to do so from Congress.”

But a servile Congress has whittled away its signal prerogative to make war. In the Tonkin Gulf Resolution in 1964, Congress gave President Lyndon Johnson a blank check signed by a responsibility-shedding Congress.

In 1973, with the War Powers Resolution, it allowed the President to commit troops anywhere in the world for up to 60 days without congressional involvement. By that time in modern warfare, the die would be cast with Congress left holding the President’s coat as he uses the power abandoned by congressional defection.

The Iraq Resolution in October of 2002 transferred war-making authority to President George W. Bush for him to use or not use at his whim and discretion. And so it came to pass that another George in American history was given kingly power with predictably disastrous results, much as the arrogance of King George III precipitated Great Britain’s break with its American colonies.

Barack Obama, after winning the Nobel Peace prize, went on to make war in places such as Somalia, Yemen, Syria, Libya, Iraq Afghanistan, and Pakistan without a congressional declaration of war. The sort of abuse of executive power has become “second nature” to us now.

But at least Obama asked Congress to authorize war on Syria, a move that contributed to the decision to avoid a full-scale U.S. military intervention in another Mideast war. There were other moments of sanity when constitutional restraint peeked through. On April 5, 1954, when President Eisenhower was under pressure to do an air strike in Indochina, he replied to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles: “Such a move is impossible” and would be “completely unconstitutional and indefensible.” (Remember when Republicans could say such things!)

Commander-in-Chief?

The term “Commander-in-Chief” is perverted to justify Congressional surrender of its constitutional war-declaring power to the royal president. The term runs like a greased pig through political discourse these days.

As Robert Previdi notes: “The President’s power as Commander-in-Chief in time of war takes over only after authority to deploy our forces has been received from Congress.” The key word there is after.

And here is another irony in this story of serially rampaging bombs-away presidents. Richard Falk writes that World War II ended with an historic understanding that recourse to war by individual nations could no longer be treated as “a matter of national discretion.”

The legal framework embodied in the United Nations Charter, largely shaped by American jurists, was “to entrust the Security Council with administering a prohibition of recourse to international force (Article 2, Section 4) by states except in circumstances of self-defense, which itself was restricted to response to a prior ‘armed attack’ (Article 51) and only then until the Security Council had the chance to review the claim.”

This is known in the literature as “the policing paradigm.” It means that state-sponsored violence can only be justified in a community context with legal and internationally enforceable restrictions comparable to the restraints we put upon our police. This civilizing understanding lies amid the smoking rubble of a world of endless war.

A president can become the despotic shepherd only when the people become his sheep. In recent decades, the vox populi has only bleated when it should have been screaming. Teddy Roosevelt said: “To announce that there must be no criticism of the President, or that we are to stand by the President, right or wrong, is not only unpatriotic and servile, but is morally treasonable to the American People.”

Yes, members of Congress, with a few noble exceptions, are groveling wimps and aliens to the lost art of diplomacy, but it’s also true that an ill-informed, lazy and indolent citizenry is neck high in treasonous negligence. In the end, the buck stops with us.

Daniel C. Maguire is a Professor of Moral Theology at Marquette University, a Catholic, Jesuit institution in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He is author of A Moral Creed for All Christians and The Horrors We Bless: Rethinking the Just-War Legacy [Fortress Press]). He can be reached at daniel.maguire@marquette.edu .

“A local rush to identify legal sources that might have justified Trump’s sudden use of force took place immediately. The waxing and waning of Article II authority under the constitution was one such identified source. Internationally, however, the problem became instantly murkier, with international lawyers advancing vague assessments as deeming such an act “not illegal” but not particularly legal either. Absent a Security Council resolution on this issue, the US had operated in a side-stepping, cavalier fashion, taking it upon itself to twin obligation and security.

“A deconflicting line, which sounded on its description to the press much like a dubious, outdated prophylactic, was used to minimise risk of engagement with Russian forces. (Immediately assume options: would the condom break? The rubber rupture?)

“For Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, Russia had failed in its role, outlined in the 2013 commitments, as guarantor that such chemical weapons ‘would no longer be present in Syria…. Either Russia has been complicit or Russia has been simply incompetent in its ability to deliver on its end of that agreement.’

“This was a theatrical show of force that was of minimal force; force without noticeable effect; penetration without outcome, a sort of historical coitus irrelevance planned to gain a domestic advantage and remind other powers that the US president can still find a trigger – and use it – if he needs to. The paltry suggestion here was that a lethal wrap over the knuckles was on its way, so ready yourself for it.

“But this shadow puppet display is at risk of proving dangerously unconstructive in so far as it places major powers in line of each other, while not necessarily impairing the targets in question with any degree of certitude.

“What is left in place is the point of moral outrage salved by a supposedly proportionate strike, not to mention the crude fetishisation of the children in whose name this attack was launched […]

“Now it is made clearer than ever that the Assad regime is to be removed, and if necessary by force, a very dangerous proposition that simply paves the way for a security vacuum as terrifyingly lethal as that left by the Iraq invasion of 2003.”

Trump Strikes Syria

By Binoy Kampmark

https://www.countercurrents.org/2017/04/09/trump-strikes-syria/

National Security seems to mean keeping Wall Street and the MIC happy and loaded with funds. National Security does not refer to doing things that would protect the citizens of the US. In fact our National Security is seriously weakened by letting most of our manufacturing go overseas, thanks to bipartisan support for that.

ffgStart making more money weekly… This is a valuable part time work for everyone… The best part ,work from comfort of your house and get paid from $100-$2k each week

…•••••••??/

Moderator please delete this hostile spam.

Good luck with peaceful protesting against this war. It was tried in Florida today with the “peaceniks” being assaulted by both Trump partisans and the police.

https://www.rt.com/news/384072-six-arrested-fight-protest-syria/

I fear it’s only a matter of time before they start gunning protesters down in the streets. Internet warriors , like ourselves , will be let off with mere life sentences in solitary.

It is worth remembering in all this chaos and insanity that the US is for the most part a colony of the western global bankers with a huge military apparatus to ensure they maintain their grip on the collective throat of humanity. That’s the only motivation behind the increasing violence being used to subdue any rivals to this system.

Russia’s back is pretty much against the wall at this point. Putin has been a cool headed strategist up to this point, but I’m sure he and his inner circle are cognizant of the motivations behind US actions. They have said as much in the past two days. It will be interesting to see how the meeting with Sec. of State Tillerson goes this week. My guess is he will be read the riot act. Whether this will have any effect on the next moves by the Deep State (Trump is certainly not in full control of foreign policy) remain to be seen.

I wouldn’t count the Russians out just yet. Their history has made them far more politically sophisticated than their ignorant counterparts in the west. The school of hard knocks is a great teacher.

According to RT, Trump promises even more war on Syria: “US President Donald Trump has sent a letter to the US Congress, informing them about the US missile strike against the Syrian Air Force base, and stating that the US will take additional action to further the country’s national interests, the White House said Saturday.” Note the wording “will” take additional action… Trump is making this open ended, basically declaring war on Syria, which usually means war on its allies.

There are unfortunately very few exceptions to the groveling wimps, and US “democracy” is very limited when nearly half the eligible voters bother to vote, the candidates often get re-elected unopposed for decades, the quality of candidates is manifestly low, the redrawing of electoral boundaries is partisan, so gerrymandering is rife, and voter suppression, mainly by Repubs, is widespread (see Greg Palast’s work). The new, extreme judge Gorsuch will help continue this downfall.

Constitution now, and for a long time, in reality, is meant only for domestic issues: recently civil rights, gay rights, environment, and state rights, and so forth. In foreign policy of imperial agenda, Constitution has been constantly trespassed, for more than a century now; and before too. Yes, there were furious debates during nineteenth century, and some debate to a certain extent recently too. But they are mostly meant to deceive the public. It is true for all Western Imperial Nations.

Those of us who are unaware of or have not kept up with, since 1981, the ideology of “End of History”, and “full Spectrum Dominance”, it will be hard to comprehend what is coming now; may be very soon.

All Media, TV, newspapers, and all that (even small town newspapers) is controlled by people such as Murdoch, a small group. With this, there is complete control of public mind (in just all Western Countries with varying degrees). With the exception of alternative Media, there is no such thing as Journalists left. They are all highly paid Hacks

Real control of Financial Institutions is in the hands of a few people.

Think Tanks are populated by NeoCons. There is not much of dissent in the Institutions of Higher Learning.

Then there is very powerful MIC, Pentagon, Intelligence Apparatus, all for waging Wars.

It seems to me that they are inching towards implementing this “Full Spectrum Dominance Doctrine” right Now.

The rumblings coming out of Europe, and NATO are ominous.

With Country run by NeoCons, and Neutered Trump with them, and Congress, Media, Masters of Financial Institutions all on board, there is a danger of Nuclear War become reality, accidental or otherwise.

Russia will probably yield in Syria. But they can not afford to yield on Crimea, and South Eastern Ukraine where inhabitants are Russian speaking, and mostly Russians and Russian Ukrainian Mix. Gorbachev from Stavropol Region in Southern Russia himself was Russian Ukrainian mix – paternal grand parents Russians, maternal grand parents Ukrainians. Russia’s very physical existence is in danger.

Regarding History, eight or nine Oblasts, which constitutes South Eastern Ukraine were part of Russian Federation and transferred by Bolsheviks (Poliburo) to Western Ukraine in 1922. Crimea was transferred to Ukraine by Khruschev (who was from Donetsk) in 1956.

In both cases it was done for political and administrative purposes.

Germany always coveted Ukraine and fought two Wars (World Wars I and II). Russia lost more than five million people in World War I and more than twenty five million people in World War II with European part of the Country utterly destroyed by the Germans with Scorched Earth Policy. Angela Merkel is very anti-Russian.

With NATO (Western) armies massed on their borders of Russia once again, they have very hard choice to make – To fight or yield and loose their sovereignty, and essentially become economic colony of Germany (and The West).

These are real perilous times in Human History.

A correction to above comments: . . . since 1991, the ideology of “End of History”, and ” Full Spectrum Dominance Doctrine” . . .

So true, Dave. It is bad enough that the Northwestern European powers (mostly Germany, Britain and the NL) think they can stick their snoot into the affairs of Russia and its borderlands inhabited mostly by ethnic Russians (or people nearly identical to them genetically, linguistically, culturally and historically, i.e., Ukraine and Belarus), but it really takes the cake for Washington, on the other side of the globe, to do so, especially when WE are so conflicted with our neighbors in the Western hemisphere. Think of it: we haughtily want Mexico and the rest of Latin America to stop trying to engage us, while we try to micromanage every country from Finland to Greece in Eastern Europe.

Yes, members of Congress, with a few noble exceptions, are groveling wimps and aliens to the lost art of diplomacy, but it’s also true that an ill-informed, lazy and indolent citizenry is neck high in treasonous negligence. In the end, the buck stops with us.

There are reasons why the U.S. Capitol is called the biggest whorehouse in the world.

I remember hearing on the radio all the Yay votes and I was jarred to hear one female vote saying Nay. That was Rep. Jeannette Rankin of Montana.

Similarly, Senator Wayne Morse (D-OR) “joined Senator Ernest Gruening of Alaska in voting against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. Senator Morse formally opposed the resolution on constitutional grounds, declaring that Article I of the Constitution would be violated if Congress surrendered its authority to check the President’s power. The Constitution establishes the President as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, but to balance and check this power the Constitution invests Congress with the power to declare war.” – http://waynemorsecenter.uoregon.edu/about/about-wayne-morse/wayne-morse-and-the-vietnam-war/

The Gulf of Tonkin incident was another of the many lies used to justify the war on Vietnam. I reminded my two senators from Oregon of their predecessor’s action but to no avail.

Bill, I am from Oregon too, and have been frustrated by Wyden and Merkley’s indifference to reality. Wyden in particular is the least communicative member of Congress I’ve ever dealt with. I literally have over 200 auto-render emails from him that promise a detailed response that I never received. My email asking them to turn off the auto-responder or replace with a message that doesn’t raise false expectations earned me only another of the same auto-responder emails.

I’m particularly bothered by Wyden’s position on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence while he silently allows propaganda memes he has to know are false to take root and flourish. But I may have moved him on the Iranian Nukes Myth with this article I wrote. https://relativelyfreepress.blogspot.com/2015/09/a-question-about-ron-wydens-intelligence.html

If you’d like to do some private plotting on dealing with the Oregon Congressional delegation please contact me at marbux pine at willow gmail hemlock com (subtract the trees).

“… much as the arrogance of King George III precipitated Great Britain’s break with its American colonies”.

I’m afraid I cannot let that pass. If you study the history of the period, you will find that King George III had very little responsibility for the “break”, mainly because – being a constitutional monarch – he had to abide by the decisions made by his ministers.

George II, although he went mad in his later years due to having inherited the unpleasant disease porphyria, was in fact a kind, honest and noble man. Better than almost all other British monarchs, and better than most American Presidents.

Good point ever since Charles the II Parliament is the supreme governing authority in the UK. King George the III was only mentioned by the leaders of the American Revolution for political reasons. Raising against the British Parliament dos have the same cache as a revolt against a king.

“I am old enough to remember the last time the United States declared war in accord with Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution. The date was Dec. 8, 1941…”

Actually, even that was redundant and done only so people could later say, “When the USA declared war on Japan”. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor was a sufficient declaration of war, and only one side needs to declare war.

(FDR, who had been an ardent young follower of all matters naval in 1904-5, knew all about how Japan had jumped the gun when it started the Russo-Japanese War by attacking the Russian fleet at Port Arthur without a declaration of war. Apparently that had completely slipped his mind by 1941…)

The American attack on Syria was far more than sufficient to establish a state of war between the two nations, which will persist until a peace is negotiated. The USA, in its astonishing arrogance, apparently no longer declares war when it attacks other nations – presumably because it believes they are so inferior to it that it is disciplining them, not going to war with them.

One day, perhaps soon, it will learn otherwise.

‘Donald Trump’s unilateral decision to attack Syria under a preposterous claim of protecting a “vital national security interest” of the U.S’.

I am still waiting to hear what that “vital national security interest” is. While waiting, I chose to re-read George Washington’s Farewell Address. You know, the one where he warned Americans to stick to trade, avoid all foreign entanglements, and especially to stay out of all foreign wars. Or else they would lose their liberties. (Yeah, right, as if that could happen).

Like Tom Welsh, I am puzzled as to what “vital national interest” the air strike against Syria was

intended to protect. That question was the first thing to pop into my head when I read the news

about it. Mr. Trump should spell this out for us.

And, I thank Prof. Maguire for his incisive article,

“Looks like an all out war, unless someone gives in.” (Kiza)

I agree. And I hope the Russians will save the world once again as they did in the Cuban missile crisis. Weren’t we told we would be the one’s who would do things like that? Where’s the “exceptional nation” when you need it most?? Is it going to be up to Putin to save the world’s chestnuts again from the madness of US leaders?

Josh, your remarks are important and enlightening for me, and I suspect many others who are ignorant of the history you reveal. So much to learn in this tangled and sordid affair of false history and skillfully planted lies and deceptions! We sure were not taught this stuff in school. As Marko said, we who share on this blog are among the few have devoted ourselves to a second education that reveals a deeper level of truth, not suspected by the great ocean of the intentionally deceived sheeple….

Yes Darrin –

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

Wordsworth

We are easy pickin’s for the savvy controllers at the top of our society’s ugly pyramid of power.

“We’re not normal. We can’t make the rest become just like us.” (Marko)

Right on Marko! How many times have I made that mistake in my thinking and behavior towards others. Then I need to reflect on the advice of the serenity prayer – accept the things you cannot change, but find the courage to change the things you can change, and preserve your sanity and serenity (what is left of it!) and don’t uselessly upset others with your awkward attempts to “convert” them to your own “extreme” views (which you think should be obvious to everyone).

This essay does a fine job of presenting a historical context and legal context for critiquing modern apathy about jumping into military action on this pretexts. An important dimension missing from the general moral and legal critique is consideration for the implications of the modern US Security State, its ability to keep truth and action secret, and its ability to lie and put out propaganda for the general public and for the US Congress. Our problem is not just that we jump into wars too quickly. It is also that the public is routinely given a false set of facts and analysis about what is going on and why the action is being taken. This power to deceive is an unintended consequence of the National Security Act of 1947 and related follow up laws. Harry Truman who was President at the time, authored an article in 1963 claiming that he had made a mistake with the creation of the CIA and that it should only have been used for analysis and not cloak and dagger operations. This was written only a few weeks after the assassination of JFK, who was secretly engaged in a struggle with CIA and Pentagon to make less war. Truman’s article only ran in the first edition of the Washington Post and then was pulled, seemingly at the request of former CIA director Allan Dulles who lied to various parties and claimed that Truman had wanted it retracted and had gone senile in his retirement. Nationally, Truman’s editorial was largely ignored and un-read. In recent years, the US government has ratcheted up its regulations for treating Security State whistleblowers in the public interest as spies and handing out long prison terms for their good service. The result of these policies is that the US is quick to blindly make war under false pretenses.

Always look at the resolve of The People to spark change. Back in the day, labor organizers were routinely murdered, beaten, jailed, and railroaded in kangaroo courts, yet they stood their ground with bloodied lip and, at times, emerged victorious. Today’s people are soft, ignorant, and too self-involved in comforting illusion for solidarity in purpose and action to exist in any meaningful manner.

We The People are enablers. True, we’ve been cultivated that way by the people who own this country, but that’s an excuse.

Darrin – “enablers” is the perfect word. Enablers are always getting something they want, so they keep their eyes closed. Thankfully, by the mere fact that Trump got elected, people are starting to wake up. He wouldn’t have had a hope in hell if people did not feel they were being lied to.

In other words, “All that is needed for evil to succeed is for good people to do nothering.”

What next?

It appears that the Russian reaction so far to the US tomahawk crime will be to extend the air-defence umbrella which covers the Russians in Syria to cover most Syrian vital installations. This will effectively become a no-fly zone for Israeli, US and other puppet country planes, at least over the SAA main military targets. Until now, the Russian air-defences were limited to two Russian bases in Syria: one naval base and one airport. The long range of the S400 system does not mean that the Russians would have risked shooting down cruise missiles or planes outside of their designated scope, as this could have compromised their primary mission of protecting the Russian assets in Syria.

Trump will probably send additional US boots into the oil-rich NorthEastern Syria, attempting to partition Syria, keep both the Syrian oil and the route for the Qatari pipeline. Israel gets to keep Golan Heights and probably gets a few additional pieces of Syria, as a “buffer zone”.

Looks like an all out war, unless someone gives in.

Kiza – don’t worry, John McCain and Lindsay Graham are in the house! They’ll protect us from harm!

This is a good sign of an informed , engaged citizenry , but we need to do it bigly :

https://www.rt.com/usa/383998-emergency-hands-off-syria-protests/

My problem with asking for an informed citizenry is that it’s impossible when all the mainstream information you come across is bald-faced lies. Since everyone tells the same lies , it’s hard for the average person to sort out. We’ll never reach a point where everyone gets their news by crawling hundreds of websites like the people here do. We’re not normal. We can’t make the rest become just like us.

We – the lie detectors – need to call the liars out , plainly and boldly. I’d suggest that when we call or email our reps or Potus , we don’t say ” Please don’t get us into any more wars ” , rather we say ” Stop lying. You lie all the time , about everything. You know it , and I sure as hell know it , so just stop. I will never , ever vote for another liar. ”

If you go to a Save the Whales protest , carry a ” Stop Lying ” sign. If you get a subscription solicitation from the NYT or WaPo in the mail , send the form back with a note saying ” No thanks. Stop lying for a change , and I might reconsider. ” When Comcast or Verizon calls to try to get you back on their TV package ( you cancelled that a long time ago , right ? ) , you say ” Your news channels are all lies , 24/7 non-stop lies. Stop all the lying and I’ll happily come back. Until then , put me on your do-not-call list. ”

When you engage CTR , ShareBlue , or any other flavor of establishment trolls online , don’t argue with them , just say “Stop lying.” and then ignore them.

Either the liars stop lying all the time , or the small minority of people who know they’re being lied to turns into a sizable majority who know. Either way , we’re making progress.

“They plunder, they slaughter, and they steal: this they falsely name Empire, and where they make a wasteland, they call it peace.”

Tacitus

You see ? Almost 2000 years of nothing but lies.

This ends , starting today.

Good comment–the society has become saturated with lying, not just in the area of politics, but also in its desperation to sell products, including for example VW’s criminality with its faulty vehicles. Call them out, yes, call them liars.

Marko, speaking of lies, I hope you approve my re-posting your excellent link yesterday from the perspective of Colonel Lang:

https://gosint.wordpress.com/2017/04/07/former-dia-colonel-us-strikes-on-a-syria-based-on-a-lie/

PS to moderator: you have already approved this link yesterday. No need to delay it.

D5-5 ,

Yes , I’m glad to see Col Lang’s post shared. It provides a sliver of hope that the truth may out on this false-flag pretext for war-for-profit in Syria.

Here’s a direct link to Col Lang’s webpage of the same post , a site where you can more good material , including among the comments ( like @ CN ) :

http://turcopolier.typepad.com/sic_semper_tyrannis/2017/04/donald-trump-is-an-international-law-breaker.html

Thanks marko. It is depressing today to read that EVERY one of the articles on this issue in the main US papers praises Trump’s act- nobody is given space for any criticism. Glenn Greenwald’s explanation is cause for even more pain-does the US public, and those of the other “Western democracies”, really fall so easily into the same trap time after time?

Thank you D 55 and Marko for the link, a definitive proof of evildoing NOT done by Russkies or Assad!!

Marko – “We’ll never reach a point where everyone gets their news by crawling hundreds of websites like the people here do. We’re not normal. We can’t make the rest become just like us.”

You are right, we are not normal. We are truth seekers, little human lie detectors. Most people do not have the time nor the inclination to spend hours every day seeking the truth, and the liars know this.

When I get solicited by the newspapers, I always say, “Why would I want to read a pack of lies?” Yes, we all need to call them out!

Wouldn’t it be interesting if the Congress now decided to impeach Trump for an act of war without their approval? This is just one more argument among many others, which his fierce opponents certainly are accumulating, to be used when needed.

The founders saw no gain in war far away, and saw the wealth of nations wasted in aristocratic power-grabs. As a result they gave the federal government no power to wage war, only to “repel invasions and suppress insurrections.”

That bears repeating: the federal government has no power to wage foreign war.

It is only the treaty that can bring authority to wage war apart from invasion. The first treaty to do that, creating NATO, was immediately abused to cause aggressive foreign wars, and has never been used for anything else. NATO must be abolished.

The problem, as the founders knew well by the warnings of Aristotle, is that demagogues become tyrants over democracy by creating foreign enemies to demand domestic power and accuse their moral superiors of disloyalty.

They can do this now because economic concentrations control mass media and elections. The founders provided no protection of US government from economic power because it was not concentrated then. The emerging middle class failed to add these protections as economic powers grew. A new War of Independence, from economic aristocracy is needed to restore democracy and eliminate foreign wars of aggression.