Special Report: A precursor of Donald Trump’s race-messaging campaign can be found in George H.W. Bush’s exploitation of the Willie Horton case in 1988, an ugly reminder of America’s racist heritage, writes JP Sottile.

By JP Sottile

America’s first “celebritician” launched his successful campaign for the Presidency with a simple, effective message: Mexicans are pouring across the border and they are bringing crime, they are bringing drugs and they are raping America’s women. That fallacious opening salvo portended the relentlessly “politically incorrect” tone of Donald J. Trump’s 17-month-long drive to the White House.

An image from a 1988 campaign ad for George H.W. Bush, featuring the menacing mug shot of convicted murderer Willie Horton.

On the campaign trail Trump described a society on the brink of chaos. He regaled audiences attending his live shows with tall tales featuring roving gangs of menacing “illegals.” He promised to ban dangerous Muslim interlopers. He warned of a Syrian fifth column skulking into the homeland through the hollow humanitarianism of a refugee-filled “Trojan Horse.” He painted a foreboding picture of African-American neighborhoods as Third World “war zones.” He promised a national crackdown on crime with controversial policing measures like the potentially unconstitutional “stop and frisk” program. He declared himself the “law and order” candidate. And he repeatedly promised to “make America safe again.”

Along the way, Trump solidified his support and confounded his critics with fictitious crime statistics that implied a national crisis due to rampant Black murderers and crime-prone immigrants. And he’s continued touting a bogus spike in the murder rate during frothy stops along his victory lap into the White House. Mostly, Trump’s calculated indifference to countervailing data allowed him to exploit a long-standing, politically profitable fear of crime despite little evidence that it is, in fact, an issue.

Not coincidentally, last year Gallup found that Americans “concern” about crime spiked to a 15-year high. The percentage of Americans expressing worry about crime skyrocketed from 39 percent in 2014 to 53 percent just two years later. That’s in spite of the fact that the aggregate crime rate remains at a 20-year low and in spite of the fact that the national homicide rate is at a 51-year low (even with the data-skewing murder rate of Chicago).

At the same time, Gallup also found that six in ten Americans also believe “racism against Blacks is widespread.” That’s up from 51 percent during Obama’s first year in office (2009). No doubt it’s a direct result from the recent barrage of shocking videos showing African-Americans in brutal and sometimes fatal encounters with police. These viral videos, along with mounting evidence that law enforcement disproportionately targets African-Americans, exposed an undeniable crisis in American policing.

Of course, the intersection between race and corrupt, unconstitutional policing is not new. Just imagine all those decades of unrecorded abuse before camera-phones finally offered corroborating evidence to widespread claims of physical assaults, harassing traffic stops, planted evidence and summary execution. But, then again, video evidence of police brutality isn’t new, either.

America got a stark look at excessive force when Rodney King’s vicious beating hit the evening news in 1991. It led to a high-profile trial. The failure to convict the offending officers then led to the “Rodney King Riot” in 1992. What did not follow was some long-overdue soul-searching about systemic racism in law enforcement. Instead, America got the 1994 Crime Bill, mass incarceration and a notable two decade-long gap in the tape between King’s beating and recent video evidence showing “high-profile” police-involved killings and a pattern of questionable treatment of Black Americans. That deafening silence is over.

Now the data shows non-Whites are far more likely to be subjected to traffic stops, to be arrested and to be incarcerated — particularly for simple drug possession. A new study by the Economic Policy Institute determined that “Black men are incarcerated at six times the rate of [W]hite men” and that “By the age of 14, approximately 25 percent of African American children have experienced a parent — in most cases a father — being imprisoned for some period of time.” The study’s authors also demonstrate a compelling causal relationship between disproportionate incarceration and the much-discussed “achievement gap” between Black and White students.

More perniciously, a recent USA Today investigation found that “[B]lack people across the nation – both innocent bystanders and those fleeing the police – have been killed in police chases at a rate nearly three times higher than everyone else.” And most disturbingly, Black and Hispanic men are “2.8 and 1.7 times more likely to be killed by police use of force than white men,” according to a controversial new study.

Perhaps that’s why the timing and the success of Trump’s tendentious, “politically incorrect” campaign is so telling. His loud arrival on the political scene coincided with the first sustained public examination of law enforcement’s excesses after a nearly three decade-long crackdown under the guise of a drug war that, according to a new study by Human Rights Watch, still arrests Americans for drug possession at a mind-boggling rate of 1 person every 25 seconds.

Also not coincidentally, #BlackLivesMatter emerged as the first forceful African-American social and political movement in decades. NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling protest against police violence became a lightening rod of controversy. And for the first time since the George H.W. Bush campaign ran the infamous Willie Horton ads during the 1988 Presidential campaign, race reemerged from the political hinterlands to take a central role in an American presidential campaign.

Racebait And Switch

Donald J. Trump set the stage for his White House run back in 2011 as the self-appointed ringmaster of Birtherism. He built his political brand by attacking the legitimacy of America’s first Black President. By the time Trump began his assault on GOP field, 66 percent of his supporters believed President Obama was born elsewhere and 43 percent believed he was a “secret Muslim.” Many of his hardcore devotees believed these falsehoods through to the end of the campaign. And many still do today.

Donald Trump speaking with supporters at a campaign rally at the Prescott Valley Event Center in Prescott Valley, Arizona. October 4, 2016. (Flickr Gage Skidmore)

With that predicate established, Trump astutely pivoted to hyperbolic and fallacious messaging about a perceived Muslim “threat.” He said Obama was “the Founder of ISIS.” And he outlined a ban on Muslim immigration. Throughout the campaign he contributed to — or simply exploited — the widespread misconception that Muslims make up 17 percent of the U.S. population when, in fact, they are a scant 1 percent of Americans. Either way, the perception was political gold for Trump.

That’s because 2016 was a campaign of perception and emotion, not facts and figures. And like a bristling political antenna, Trump picked up the growing unease in rural and suburban America and masterfully transmitted broad emotional, identity-based appeals rooted in the nation’s shifting demography. He expanded traditional racial parameters of who is dangerous to include Muslims, Mexicans and immigrants in general. He connected voters’ anger with the sense that America had been “lost.” He promised to return America to a supposed state of greatness.

Unsurprisingly, the strongest bastions of Trump’s “red meat and potatoes” support were, according to the Wall Street Journal, those small Midwestern towns and counties that experienced the fastest-shifting ethnic, religious and racial demographics over the last 15 years. On Election Day, his unshakable base of White Working Class males swelled, according to a FOX News exit poll, to include educated Whites, Whites of greater economic means and White women. Yes, he brought the vaunted Reagan Democrats back to the Republican fold. But he also got an unexpected boost from higher income Whites and suburban White women.

Despite the data, some argue that this coalition of Whites is not a “White backlash” vote. Trump’s slightly better than Romney (by 2 points each) performance with Black and Latino voters did exceed quite low expectations (although he still only got 8 percent of African-Americans). It is also true that a combination of Hillary Clinton’s vulnerabilities, economic dissatisfaction and thirst for change all contributed to Trump’s win. But that doesn’t fully explain the stark Whiteness of his base — which produced an Electoral College victory centered specifically in so-called “Duck Dynasty” America and a notable overall popular vote loss in aggregate America.

How Did Trump Win?

So, how did Trump form a strange coalition of the so-called Alt-Right movement and its motley crew of White Nationalists, Klansmen and disgruntled Caucasians with a surge of more educated, more affluent Whites, suburban women and the reborn Reagan Democrats?

The run-down PIX Theatre sign reads “Vote Trump” on Main Street in Sleepy Eye, Minnesota. July 15, 2016. (Photo by Tony Webster Flickr)

Trump resurrected a well-established and all-too successful political ploy that takes racism and perniciously hides it in real issues — like crime, poverty, taxes, job scarcity, social welfare policy. He effectively underlined issues like economic insecurity, fear of terrorism and resentment against trade with politically incorrect, ethnically-themed and racially-conscious messaging. Like his use of faulty crimes statistics, he used these appeals to draw out the grudges and grievances of people who felt transgressed by politicians and/or were fearful and uneasy about the direction of the country.

These grudges simmered underneath the palpable economic grievances of working-class Americans and, specifically, working-class White Americans. But this was about more than just economic dislocation. Making America great “again” also spoke to fears about the changing face of the nation.

Trump hearkened back to a time before all those “politically correct” demographic changes so colorfully embodied by Obama’s coalition. Those were the very voters Hillary Clinton pursued. Instead, Trump built his monolithic, monochromatic base with a well-worn process of coding that replaces overt racism with far more complicated political messaging that marbles issues with bigotry, xenophobia and racism.

For example, Trump’s economic messages about Mexican immigrants and wily Chinese negotiators can appeal to racists and xenophobes while also appealing to people who are not bigots, but endure real or perceived economic hardships that appear to be addressed by expelling immigrant labor or renegotiating “fairer” trade deals.

In other words, it is possible to rationalize a racially-motivated policy as “not racist” because you don’t have to irrationally “hate” Mexicans to agree with a policy of removing an “illicit” labor pool. Nor do you have to “hate” clever Chinese leaders for doing to America what you think American negotiators would’ve done to the Chinese if America’s leaders weren’t so darn “stupid.”

The issues of wage decline from immigration or deindustrialization from bad trade deals can therefore be “race neutral.” It can be easily rationalized as “not racist” to want enforceable borders and better negotiations. It can also seem wholly justifiable to shut down Muslim immigration from specific countries. It possible to believe it’s not based on their religion or ethnicity, but because terrorists (thanks to a conveniently squishy application of the term) always seem to come from “over there.” Therefore, it isn’t technically racist to just want to stop terrorism. Just like it wasn’t necessarily racist to want less crime back in 1988.

Back then, the infamous Willie Horton ad and the relentless “law and order” messaging of the Bush campaign linked crime with Black men to build an electoral victory. The upshot then was a two-plus decade-long merger of crime with racist tropes about Black men. The upshot now is the marbling of economic unease with racism against Mexicans, ethnonationalism against Chinese and fear of Muslim interlopers. And then like now, this powerful style of messaging made it possible to explicitly embrace or tacitly accept prejudicial proclamations that would’ve otherwise been unacceptable.

In fact, there’s a certain symmetry to Trump’s meteoric rise and the conclusion that American law enforcement still grapples with systemic racism. His posture as the “law and order candidate” tapped into the backlash against the backlash against the era of mass incarceration. His consciously abrasive style resurfaced a deeply encoded racism that — like hundreds of thousands of Black men — was locked away into the prison system during the War on Drugs.

Law And Order

Racism has been evermore deeply encoded into the criminal justice system since the civil rights movement scored key victories in the mid-1960s. The old system of Jim Crow was methodically replaced with a “New Jim Crow” that, as Michelle Alexander so painfully detailed, turned incarceration as tool of de facto re-segregation. Controlling African-Americans was expressed as a need to “get tough on crime.” And the phrase “’law and order” became a subtle way of playing on racial fears and trading in a less overt forms of racism.

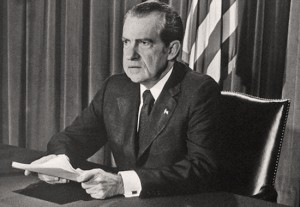

When Richard Nixon ran on “law and order” during the tumult and race riots of 1968, there was little doubt what he meant. It was about getting a handle on angry Black Americans reeling from the violent loss of Martin Luther King, Jr. It was also a coded response to the new socio-political reality of post-Jim Crow America. At the same time, the Civil and Voting Rights Acts meant White America had lost (at least technically) its legally sanctioned place atop the racially stratified system. America was changing and not everyone was happy about it.

What arose out of that toxic cocktail of backlash and resentment was the racially conscious “Southern Strategy.” In 1972, Nixon’s political team leveraged the “old” Jim Crow South into a sweeping electoral victory. Nixon’s “Silent Majority” of disgruntled working, middle-class, suburban and Southern Whites transformed the Republican Party for decades to come. Notably, 1972 was also the year Nixon officially declared the War on Drugs.

According to Dan Baum, Nixon’s drug war might’ve actually been a surreptitious counter-attack against dissent on both the political Left and, perhaps most balefully, on an increasingly forceful Black activist movement. Writing in Harper’s, Baum cites infamous Nixon aide John Ehrlichman who said Nixon secretly turned the criminal justice system into a tool of political payback and racial control:

“We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

In other words, the quite real issues of drugs and crime were weaponized for political and racial purposes. Nixon’s War On Drugs and his call for “law and order” became nods and winks to law enforcement as they cracked-down on “crime”… and his opponents. Successive GOP campaigns focused on these quite real issues of drugs and crime. They also paid no political price for the disproportionate outcomes of the policies — particularly those faced particularly by Black Americans. It didn’t become an issue because the issue wasn’t officially “racism.” It was law and order.

By the time former California Governor and committed drug warrior Ronald Reagan made his own “law and order” appeals during the 1980 campaign, many White voters had fled to the suburbs while many White working-class voters grappled with the economic unease brought on by imported Japanese cars. They struggled with chronic economic stagflation and felt trapped in a sense of national malaise. Some were looking for scapegoats and blamed government programs that supposedly were helping Blacks and other minorities. Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?

The Rise of Lee Atwater

It was in this milieu that a whip-smart, guitar-playing Southern-born GOP strategist named Lee Atwater honed the racial massaging that would eventually lead to the most notorious campaign ad in American political history. However unintentionally, he helped to expand Nixon’s War on Drugs into a generational crackdown on Black America. And he created a bipartisan consensus on crime that ultimately haunted Donald Trump’s opponent

President George H.W. Bush “jamming” with campaign strategist Lee Atwater during inaugural festivities on Jan. 21, 1989. (Photo via Wikipedia)

During a now-infamous 1981 interview, Lee Atwater explained the evolution of coded racism from its earliest iteration in the Southern Strategy to its penultimate expression during the 1980 campaign to elect Ronald Reagan. Said Atwater:

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger.’ By 1968 you can’t say ‘nigger’ — that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.… ‘We want to cut this,’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘Nigger, nigger.’”

Sadly, Atwater’s language was far less shocking in 1981. But Atwater’s blunt talk (which was uncovered by James Carter IV in 2012) exposed a fundamental truth about American politics and the evolution of racism in American politicking. As a political matter, racism had to be increasingly coded over time. The further America got from the Civil Rights Act, the less acceptable it was to be overtly racist. Instead, race-based appeals were surreptitiously transmitted through coded messages. This was something Lee Atwater knew from first-hand experience.

Atwater — along with his friend Karl Rove — was a rising star in the College Republicans at the same time Nixon’s Southern Strategy was reshaping the party. The South Carolina native then cut his sharp teeth on his home state’s rough-hewn politics. He even worked for former Dixiecrat Strom Thurmond. But his big leap to the big time came after he helped The Gipper win a racially-tinged knife fight in the suddenly crucial South Carolina primary. In 1981, Atwater was given a spot as White House advisor as a reward for helping plot Reagan’s own Southern Strategy march to the White House.

Frankly, the Gipper was no stranger to the political power of the wedge issue or the code word. He’s long been accused of delivering smoothly-edged, racially-coded messages before, during and after his successful 1980 campaign. Atwater’s interview adds to that record, particularly since Reagan pioneered the conflation of both taxes and social welfare policy with the resentments against Black Americans. In 1976, he launched specious attacks against a fallacious cadre of so-called “Welfare Queens.” He linked “welfare reform” and “State’s Rights” during a purposeful 1980 campaign stop in Mississippi. As President, he often derided supposed “dependency” on government.

These coded messages implied that Blacks wantonly fed off the public trough through “government handouts”. It was implied that cutting off the “free” flow of funds into that trough would force “personal responsibility” onto a recalcitrant group of “lazy” Blacks living off harder-working Whites. Unsurprisingly, “personal responsibility” became a popular GOP code-phrase for three decades.

These messages are louder and clearer given Atwater’s 1981 interview.

But as conservative blogger John Hinderaker rightly points out, Atwater was not just saying coded racism works. He was also saying that blatant racism does not. Atwater — who counted African-Americans among his closest friends, who struggled to prove himself through an ill-fated stint on the Board of Trustees of Howard University and who even cut a blues record with B.B. King — may have actually believed this was “progress.” And it some strange way it probably was.

Like a discordant film negative, the Southern Strategy and the Silent Majority revealed the changing reality of American society. Crass, blatant racism was being pushed out of the public square. That was a good thing. But coded messages remained a potent political tool.

And when Atwater decided to “Strip the Bark” off of Democratic presidential nominee Michael Dukakis during the 1988 campaign and, more importantly, to make convicted murderer Willie Horton his “running mate” … he created a whole new socially-acceptable category of racial profiling — the drug-dealing superpredator. He turned the 1988 election into a de facto referendum on the criminality of Black males. And his winning strategy set the tone for an era of mass incarceration.

Changing the Narrative

In 1988, night was falling on Morning in America. The “Black Monday” crash of 1987 on Wall Street shocked the economy out of its freewheeling frenzy. The nation’s capital was in a yearly competition with other major cities for the ignominious title “Murder Capital of America.” And the often-ridiculed “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign metastasized into a full-on hysteria about a new drug — the dreaded scourge of “crack cocaine.”

Less than two years earlier, the media mania after the drug-overdose death of college basketball star Len Bias galvanized a congressional response to the growing national freakout about cocaine and especially its cheaper derivative “crack,” which was associated more with the Black inner-cities. On Oct. 27, 1986, the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 became law and its almost comically disproportionate punishment for crack possession versus powder cocaine launched a process of African-American incarceration that can only be described as systematic.

Although tons of “upscale” powder cocaine had long fueled many of Wall Street’s financial high-rollers and some of Hollywood’s creative lows, the cheap, portable rocks became an obsession for politicians and law enforcement. Over the next two years, the “crack crisis” reached a fever pitch. The War On Drugs unfolded much like a domestic Vietnam War as fear of well-armed gangs, bleak tales of crack babies and relentless “if it bleeds, it leads” coverage by local television news brought the growing violence into America’s safe suburban living rooms every night at 5, 6 & 11.

Also unfolding every night was the high-stakes drama of the Iran-Contra scandal. The wounded Reagan Administration limped through the Congressional hearings of 1987. Reagan’s approval rating dropped to a four-year low. In his final year more Americans actually disapproved than approved of the Gipper. And the stench of constitutional crisis threatened the Presidential aspirations of Vice President George H.W. Bush.

During the 1988 campaign, Vice President Bush’s comical “out of the loop” defense undermined his competence and underlined his shiftiness. On one hand, Newsweek ran a cover story about Poppy’s battle with “The Wimp Factor.” On the other, The Nation ran a story indicating Bush may have been a long-time CIA operative. And, perhaps most ominously for team Bush, Sen. John Kerry’s “Kerry Committee” had been digging into allegations of drug trafficking by Reagan’s beloved Nicaraguan Contra rebels and found damaging evidence of a cocaine connection that first came to light in a 1985 story by Brian Barger and Robert Parry for the Associated Press.

The campaign to succeed Reagan looked like a big mess.

The lingering scandal, along with signs of a coming recession, catapulted a mild-mannered straight-shooter from Massachusetts, its Governor named Michael Dukakis, to the top of the Democratic ticket. At the time, Dukakis’s desire to restore competence to a government looked like a winning pitch. In fact, the unfolding Iran-Contra scandal and its relentless buck-passing was a primary motivation for the accountability-obsessed Dukakis. As he’s since said, his run was motivated by a desire to clean-up Washington after the Iran-Contra mess.

As such, the stern and technocratic Dukakis offered a starkly reliable antidote to the malicious maelstrom of the late-stage Reagan White House. For him it was going to be a campaign of facts, figures and forthrightness. Initially, the American people bought his brand. By the time the Democrats triumphantly left their convention in Atlanta, Dukakis opened up a 17-point lead over Vice President George H.W. Bush and Bush’s political team — led by Atwater — struggled to shift the conversation away from the scandals and away from a referendum on competence. Lee Atwater turned to the reliable voter response from the issue of crime.

Really, it was a no-brainer for the GOP’s boyish wonder. He had to change the narrative. And he had to hit voters in the gut. At the time, violent crime reached record highs and the media was already obsessed with the issue. His plan to “make Willie Horton” Dukakis’s running-mate simply took the most effective tool in America’s historical woodshed (the issue of race) and married it to a quite real issue (the rise in crime).

Horton, a convicted murderer, had raped a White woman while out of a Massachusetts prison on “furlough,” a prison-reform strategy with the goal of allowing prisoners to gradually reintegrate back into the community. Atwater used the Horton case as a crude tool to strip the bark off of Dukakis, who was also tied to liberal softness that opposed the death penalty and was portrayed as tolerating marauding urban drug criminals. The strategy quickly peeled ten points off Dukakis’ lead.

By late August, an unremitting focus on crime, felon furloughs and the death penalty (which Dukakis opposed) — along with an ill-advised ride in a tank by the bobble-headed Dukakis — flipped the race. Bush was up by four points going into September. But Atwater wasn’t done. His transformation of the issue crime was just beginning.

The Bush Campaign first featured Willie Horton in stump speeches during the summer of 1988. But those speeches lacked the one thing that made the ad so infamously toxic — William Horton’s iconic face. So, under Atwater’s guidance, the appropriately-named Americans for Bush Political Action Committee (AMBUSH) produced ads that not only framed the contest as a “law and order” election, but it reframed one of America’s oldest racist tropes.

Horton, a convicted murderer, had been released on a weekend furlough when he stabbed a man and “repeatedly” raped his girlfriend, a storyline that the narration bluntly pointed out under the image of Horton’s mugshot. It then paired Horton’s glowering expression, sullen eyes and wildly unkempt afro with the memorable phrase “weekend passes for murderers.” It was ostensibly an ad about crime, but it scored a direct hit by rebooting a dangerous canard first highlighted on film by D.W. Griffiths’ Birth of a Nation—the Black man as sexual predator.

The first Willie Horton ad had a limited run beginning on Sept. 7, 1988. It was followed up by the notorious “Revolving Door” ad a couple weeks later. That ad featured a bevy of criminals heading into and out of prison — with, as writer Ismael Reed pointed out, the lone Black man in the line slyly looking up when the narrator said the word “rape.” Again the message was clear—if you are afraid of crime you should be afraid of Black men. Taken together, those ads turned a not-uncommon furlough program into political poison.

Although the ads did not by themselves alter the outcome of the election, they swirled into a national controversy. Even if the ad never ran on your local station, you were likely to have seen, heard or read about Willie Horton. The ads effectively linked the national hysteria about crime and crack with a racially-charged portrayal that inexorably intertwined the issue of crime and with the faces of Black men. It normalized a specific, spurious portrayal of Black male criminals.

The Kill Switch

The two ads also set-up CNN anchor Bernard Shaw’s famous opening question to Dukakis in the second Presidential debate. That question: “If Kitty Dukakis were raped and murdered, would you favor an irrevocable death penalty for the killer.” Dukakis quickly responded, “No I don’t Bernard, and I think you know I’ve opposed the death penalty all my life.” Dukakis went on to say he wanted to fight a “real war, not a phony war against drugs.” He proposed interdiction overseas and drug education at home. But none of that mattered. His death penalty answer was his campaign’s death sentence.

It was also the beginning of a post-Horton era in American society and criminal justice. Approval for the death penalty spiked to an all-time high in the years immediately after the 1988 campaign. The Black incarceration rate accelerated to society-shifting levels. It was followed by controversial new policing tactics that escalated arrests for trivial offenses and that imposed draconian punishments for drug crimes, like Stop and Frisk (1990), Broken Windows Theory (early 1990s), asset forfeiture (jumped 58 percent in 1990), “Three Strikes” laws (1994-6) and the “zero tolerance” focus on drug users and “street level” crime over large-scale distributors (1988).

Like the outcome of the election of 1988, it’s impossible to quantify the exact effect of the Willie Horton ad on the decade-long crackdown that followed. Like Trump’s politically incorrect campaign, it relied on perceptions and feelings. Not fact and figures. Atwater’s law-and-order campaign was in code, so it’s hard to decipher the impact. But, just like the beating of Rodney King, the Willie Horton ad did not inspire soul-searching about racism. Instead, it signaled the beginning of an era of public and political tolerance for excesses in the name of law and order. King’s beating may have been an outgrowth of the excessive policing these politics engendered. But the outrage and riot that followed the acquittal further cemented the racial divide between Atwater’s new coalition and those left behind on the drug war’s front lines.

The Scene of the Crime

Lee Atwater’s successful “law and order” campaign quickly evolved into a bipartisan consensus on crime. In effect, Atwater built a new “law and order” majority that merged the Southern Strategy with Reagan Democrats and, most importantly, the moderate, White, Baby Boomer Middle Class voters now firmly planted in America’s suburbs.

By 1992, “moderate” Democrats — like Southerner Bill Clinton — acknowledged the power of the GOP’s “tough-on-crime” approach. Then-candidate Clinton’s promise to put “100,000 cops on the street” catered specifically to the War on Drugs-based constituency that Atwater created. In a sense, racism was sanitized because it had become so inexorably subsumed into the category of crime. The consensus against crime was easily rationalized as “not racist.” But, like so many things, Clinton took it a step further.

During his run against President George H.W. Bush, Clinton made certain to demonstrate his separation from left-wing sympathy toward Black anger by publicly upbraiding a rapper named Sista Souljah. In fact, “Sista Souljah moment” became political shorthand for triangulating against your own base by attacking a vulnerable proxy. She was one of many rappers making stark, musical statements against White racism and against police brutality in Black communities.

And in a moment of blatant grandstanding, Clinton excoriated her racialism. Of course, he didn’t dare confront N.W.A. or Ice-T or any of the higher profile artists reporting from the frontlines of the Drug War. Instead, he took advantage of an easy target of opportunity to triangulate against African-Americans and traditional Liberals in his own party. It instantly burnished his crime-fighting credentials, which included stern enforcement of the death penalty. And it worked like a charm.

Clinton expunged the Democrats’ perceived “weakness” on crime. He distanced himself from the legacy of Dukakis and the much-derided moniker “liberal.” Then as President he lorded over an escalation of the War On Drugs. By 1994, Clinton signed the draconian, bipartisan 1994 Crime Bill. He shepherded through welfare reform — a.k.a. the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act — in 1996. Yup, there’s that “personal responsibility” code word Reagan loved so much. Clinton turned it into policy. And during the State of the Union that same year he made another Reaganesque turn when he announced that “the era of big government is over.”

Atwater’s triumph was complete — but he wouldn’t live to see it.

Lee Atwater was struck by an aggressive brain tumor in 1990. Some felt it was karma. Suffering mightily, he literally spent his dying days apologizing for the ad, apologizing to Dukakis and fighting in vain to clear his name from the charge that he was racist.

The Bitter Ironies

Atwater’s bare-knuckled campaign was a direct response to G.H.W. Bush’s weakness on Iran-Contra. If the campaign had been about Bush’s competence, his trustworthiness or his role in the Reagan White House, Houston would’ve had a problem. So, the focus on high crimes committed in the Reagan White House was replaced by street crimes committed in urban areas.

After all, Atwater didn’t need urban voters to build an electoral victory. Atwater simply changed what should’ve been a national referendum on a constitutional crisis and replaced it with a referendum on law and order, on crack cocaine and on the furloughed Black male predator roaming freely in the urban decay of a changing America.

Most importantly, the Iran-Contra all-stars desperately needed Poppy Bush to retain control of the Executive Branch, particularly with independent counsel Lawrence Walsh’s investigation churning in the background. Certainly, they could forget getting pardoned under the notoriously staid Dukakis.

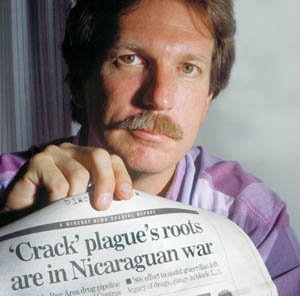

And although Gary Webb wouldn’t start his groundbreaking investigation into the Contra-cocaine connection to the crack epidemic until 1995, the Kerry Committee already had cracked open the lid on Contra narco-trafficking. No doubt, the scandal’s biggest players knew there were more damning revelations looming behind the firewall. Losing the White House in 1988 could’ve been much more than a political rebuke. It could’ve meant prison. And that’s the bitterest irony.

Atwater helped preserve the legal firewall between the perpetrators of Iran-Contra and the seediest, most destructive elements of that scandal … by repurposing the fallout from a drug war that was partially due to the CIA-tolerated crack cocaine pipeline into South Central L.A. In essence, the CIA’s protection of Nicaraguan Contras instrumental in that pipeline helped generate part of the “law and order” political justification that ultimately kept the covert perps in power. It was an all-too vicious circle for Black Americans that got them coming and going.

The final irony is that nearly three decades later, Hillary Clinton would bank on African-American turnout to win the White House. But they didn’t quite turn out in the numbers she had hoped. Despite winning the popular vote, Clinton lost the “Battle of the Bases” in Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin. Her racially diverse urban base was trumped by Trump’s monochromatic cadre of supporters in those states’ rural counties. Was that flaccid Clinton turnout partially because she was haunted by her own support for the crime crackdown consensus that got her husband elected and reelected?

Perhaps even more damning were her not-so-coded comments in support of the 1994 crime bill when she warned of Black “superpredators.” She even said society needs to “bring them to heel.” Whether or not that specifically cost her the White House, it certainly didn’t help. She underperformed Obama’s 2012 total with African-Americans by 5 points (Clinton: 88 percent vs. Obama: 93 percent). It also didn’t help that 1.4 million Black Americans had also lost the right to vote thanks to the grinding incarceration she’d once supported. Like far too many others who actually lost years of their lives to needless incarceration, she too was haunted by ghost of elections past. She merely lost the White House. Too many African-Americans lost far more.

The Ghost Of Willie Horton

Although there are as many interpretations of Donald Trump’s win as there are blatherati on a CNN panel, the one undeniable thru-line of his campaign was his effective use of both dog whistling and blatant bullhorning. Like the role of Willie Horton in the 1988 campaign, the exact electoral impact of Trump’s encoded messaging is hard to quantify.

Former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton speaking with supporters at a campaign rally in Phoenix, Arizona, March 21, 2016. (Photo by Gage Skidmore)

As Peter Grier pointed out in the Christian Science Monitor, Trump wasn’t elected “solely by [W]hite men in pickups who fly Confederate flags.” He did get “almost 63 million votes,” and, Grier continues, “you don’t get that many without winning some women, some college-educated voters, and even some minorities.” True enough.

But also like 1988, the question is far bigger and the impact potentially far deeper than one electoral snapshot in time. Whether Trump won because of or in spite of his resurrection of racially encoded messaging, the simple fact is that his win gave racists and bigots and, for that matter, misogynists a reason to feel both validated and vindicated. Trump normalized the use of so-called “politically incorrect” language that, whether intentionally or not, expanded the old boundaries of racial coding to encompass Mexican criminals, Muslim terrorists and Chinese economic thieves … and even made sexual assault seem acceptable.

Will it also translate into a so-called deportation force that will eject millions of Latinos? And what does it mean to eject Latinos “humanely”? If you have to say you’ll do something “humanely,” it probably means it could easily become inhumane.

Will Latinos — who are already disproportionately subject to criminal penalties — become targets of crackdown on “narcoterrorism”? Like Trump on crime, his pick for Homeland Security wildly overstates the problem … and ignores the true perpetrators of the opioid crisis in the pharmaceutical industry.

Will Trump’s gung-ho pick for Attorney General — the racism-tainted Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Alabama — leverage crime fears into a recharged War on Drugs? Will it happen in spite of voter-led efforts to dismantle it? Does the sudden rise in prison stock prices portend bounce-back for prison privatization and an incarceration rate that’s finally relenting a bit? Will #BlackLivesMatter become a political target under a hostile Department of Justice?

Will Team Trump’s notable hostility to Islam and his supporters’ comfort with the Muslim ban translate into a loyalty test? Will hate crimes continue past a post-election surge? And will it whip up into a wider war if and when one of his hotels is targeted by a lone wolf?

And will Trump’s mantra-like recitation of China as the culprit behind the deindustrialization of America (instead of the true culprits at Walmart and on Wall Street) lead to a trade war … or worse?

While those among Trump’s supporters can claim that none of these possibilities is necessarily indicative of racism, the problem is that he’s marbled these issues with race. Like it or not, people voted for whole package, not just the issue. Frankly, it’s another reminder — perhaps an all-too bitter one — that how elections are won often matters just as much, if not more, than the victory itself. It’s a cliché, but the journey does matter. And Donald J. Trump’s journey to the White House followed a well-worn path through a half-century of racially coded messages littering the campaign trails of the post-Civil Rights Era.

JP Sottile is a freelance journalist, radio co-host, documentary filmmaker and former broadcast news producer in Washington, D.C. He blogs at Newsvandal.com or you can follow him on Twitter, http://twitter/newsvandal.

To me this painful-to-read article is an effort to demonstrate how criminality from the early history of our republic lives on like a simmering virus in the bloodstream of America today. Just as our initial disposition to see this land as whiteman’s land–not “redskin’s” land–has meant an enduring disposition among us to dispossess others of their rightful possessions and freedoms, so too our incredible cruelty toward kidnapped Africans and their descendants has meant an almost ineradicable disposition to see African-Americans–particularly male African-Americans–as legitimate targets today. Focusing on the use made of Willie Horton–a far from typical black male–by the campaign of the senior Bush, Sottile attempts to demonstrate how convenient this simmering virus of contempt can be. He makes a detailed examination of how the virus has come to be wrapped in a seemingly admirable concern for law and order. He admits more than once that it’s hard to quantify just what degree of influence this virus has in present affairs. Those who refuse to see racism as a persitent presence, will no doubt dismiss the article out of hand. Those willing to begin reading with some vote of confidence, stand I think to learn a great deal from Sottile’s scholarship and analysis.

Read “Orders to Kill” by William F. Pepper, Martin Luther King’s last attorney. America has 17 secret intelligence agencies, 17, all of whom are dependent upon Americans’ allegiance. Four white people were murdered at Kent State by the National Guard May 4, 1970. America was terrified of MLK running for president originally with Dr. Benjamin Spock but later after RFK declared, possibly as his running mate. Both MLK and RFK were assassinated by our government after the later won the California primary and both Sirhan SIrhan and James Earl Ray were innocent patsies. It does not matter your color as much as your ability to threaten our shadow government and the cesspool of cash they generate running drugs, overthrowing nations and stealing natural resources. The manipulation of Americans with an cumulative ninth grade educations is simply the psychological engineering of madmen and we are played like an ole piano. You know what they say about blind allegiance? It’s blinding. peace.

I know very little about American politics and even less about racism. Furthermore neither subject interests me very much. Consequently I am not qualified to dispute the author’s conclusions.

However, concerning the author’s method, I notice significant omissions in the narrative. So I think the author suppresses information that might contradict his focus on racism as the privileged explanation for everything that happens in that country, which in turn seems to reflect a rather tiresome national obsession.

Specifically, two statements that I find glaringly biased are:

1. “almost comically disproportionate punishment for crack possession”.

According to contemporary reports, the disproportionate punishment for crack possession was enacted at the urging of BLACK congressmen. Accordingly it is extremely problematical to construe such disproportion as the outcome of racism.

2. “his winning strategy set the tone for an era of mass incarceration“. This implies that blacks started being locked up more often around that time on account of crack and/or racism. However there is no mention of the deleterious effect of immigration on black Americans, which is the subject of a paper published in 2006 by the National Bureau of Economic Research entitled “Immigration and African-American Employment Opportunities: The Response of Wages, Employment, and Incarceration to Labor Supply Shocks” http://www.nber.org/papers/w12518

I suspect that the author’s apparent bias in favor of explaining things in terms of racism may affect the validity of his conclusions.

PS moreover I find it disingenuous to cite as sole authority for the claim that immigrants don’t commit more crimes, an individual, David Bier, who is an immigration policy analyst at the Cato Institute. From personal discussions I have had on unrelated policy matters with Cato institute flacks, I know for a fact that they shamelessly push their neoliberal agenda on every possible occasion. This agenda includes open borders (a favorite capitalist trick to lower wages).

Re China – I read that at one point 60% of all goods imported into the U.S. from China were from U.S. multinationals operating in China. If so, then Trump placing tariffs on imported goods would hurt the U.S. multinationals, perhaps causing them to bring manufacturing back to the U.S. Trump wants “fair” trade because “free” trade has not been working out for U.S. workers. Goods would probably cost more (last longer too, though), Walmart’s business model might be harmed, maybe they’d even go under, but you can’t send jobs overseas and still expect unemployed workers to buy your products.

Walmart’s employees are subsidized by the taxpayers (food stamps, housing allowances, etc.), and for what? So Walmart’s shareholders can get richer? I guess that was the point of it all. Low-income people on disability, Social Security, the elderly, the unemployed or part-timers, and the poor are Walmart’s base customers, and they’re all getting a pay check from the government. Nice business model.

But you end up with a hollowed-out country and disgruntled citizens, which is why they voted for Trump.

In China, there was a symbiotic relationship between the Chinese elite and the U.S. elite. Both got rich.

JP – what you see as racism, I see as common sense. Obama has been deporting Latinos by the thousands, and yet I don’t hear anyone calling him a “racist”. Could it be because he’s black, and we just don’t call blacks “racist”?

“And will Trump’s mantra-like recitation of China as the culprit behind the deindustrialization of America (instead of the true culprits at Walmart and on Wall Street) lead to a trade war … or worse?”

Maybe I’m beginning to see the difference between you and I. I try to look at both sides of a question. BOTH China and Walmart are culpable in my eyes, whereas you just see Walmart. The U.S. made China. If the U.S. had not gone in there with their technology (and they were invited in by the Chinese elite, don’t forget), they’d still be back in the Stone Age. A commenter said the other day: “If you see a wealthy Chinese millionaire, you’re looking at an environmental criminal. If you see a wealthy Chinese billionaire, you’re looking at Mr. Burns X 1000.” In their pursuit of riches, the Chinese elite have polluted and destroyed China, all while escaping to the West with their corrupt money. When the Chinese people finally figure out what’s been done to their country, they’ll hang these elite.

You just see Black Lives Matter, whereas I see Black Lives Matter and George Soros, Mr. NGO. You know, the same guy who was responsible for paying people to disrupt Trump rallies, stir people up, then turn around and label Trump supporters as violent.

I see blacks killing blacks mostly, hurting themselves. I see 73% of all black babies born are to unwed mothers. 73%! That’s going to come back to bite, no matter what color you are. I see good people who have been made dependent on the government for their very survival, and they’ve taken the bait. They don’t have a choice? Really? Nice to have dependents – they almost always vote for you.

http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2013/jul/29/don-lemon/cnns-don-lemon-says-more-72-percent-african-americ/

I see stupid laws putting blacks away for dumb drug offences. Let’s legalize drugs, take the crime out of it, empty the jails, send the campaign-contributing private prison contractors packing.

Good enough article, but not enough of the other side of the equation. I’m pretty sure when Trump thinks of the factories he’d like to see humming again, he sees black people working there too.

“I’m pretty sure when Trump thinks of the factories he’d like to see humming again, he sees black people working there too.”

I agree with you that Trump sees blacks working in them too, no doubt.

Unfortunately Trump also envisions those factories humming along with a stagnating minimum wage and sans worker safety laws and robust labor unions. The effluents and other externalities the factories belch out that Trump foresees will be under scant regulation, free to pollute to their hearts’ content. And ultimately the products those factories sell to the American consumer will come with a huge ‘buyer beware’ caveat since consumer protections are likely to be eviscerated and toothless.

All that being said, yes, by all means we need to bring back family supporting, living wage jobs to the heartland but they need to be regulated in the public interest. Trump’s rhetoric has been quite good regarding rebuilding our industrial base, he gets kudos for this, but when it comes to everything else that I’ve just pointed out he leans toward being an Ayn Rand disciple.

“Unfortunately Trump also envisions those factories humming along with a stagnating minimum wage and sans worker safety laws and robust labor unions. The effluents and other externalities the factories belch out that Trump foresees will be under scant regulation, free to pollute to their hearts’ content. And ultimately the products those factories sell to the American consumer will come with a huge ‘buyer beware’ caveat since consumer protections are likely to be eviscerated and toothless.”

You don’t know what Trump envisions at all. You’re just making it up. “Trump envisions, Trump foresees, likely to be” – no one knows what is “likely”.

There are certainly strong pro-globalization voices out there fighting Trump. Not a word from them re the absolute ongoing disaster of Fukushima, absolute silence on this, yet very vocal on what Trump is “likely” to do.

Trump has stated that he wants fewer regulations on business. The consequence of that is easy enough to predict and no one needs to “just make it up”. The reason we have those regulations is precisely because businesses did not voluntarily operate in a manner that keep rivers and air clean or insure the consumer safety of their products.

“So, how did Trump form a strange coalition of the so-called Alt-Right movement and its motley crew of White Nationalists, Klansmen and disgruntled Caucasians with a surge of more educated, more affluent Whites, suburban women and the reborn Reagan Democrats?”

No, no bias there.

My reading of the election was that those disgraceful “whites” were concerned about their jobs, about the offshoring of jobs, about the empty factories that line their cities. Yes, they were also concerned about illegal immigration, which serves to hold down their wages, and puts a tremendous strain on education/medical/housing costs. Wow, imagine citizens wanting to actually limit who comes into their country! Why, that’s racism!

Let’s imagine they were white Russians south of the border who were flooding across. Do you think it would be any different? Really? Get a grip.

The News Vandal strikes again! Really enjoyed the historical perspective in this piece. I didn’t read any bias either left or right, just a retelling of the facts as they relate to the use of race in presidential elections. I don’t think it was the intent or purpose of this piece to endorse any person or party, or say if any one person was or will be good for the country. Excellent analysis, excellent perspective. If you find yourself angry or feeling like your side was not properly treated in this article, you are probably heavily biased one direction or the other.

Here is a prime example of why I am so proud to work with you JP. Now if the Trumpeters can get over their morning sickness in the artist formerly known as America Inc. can look at what is happening around them, we may have a shot to heal a bit before the viral sentiment over substance agenda forces freedom to rise from ashes alone. Hope and Change was simply re-booted like a good Hollywood psychosis always is , recycled and repackaged for people that ignorantly believe they are White. Try being human beings first before you embrace the sub-divisions , embrace freedoms instead of leaders for a day. It may actually change the pre-arranged suicidal agenda that dictates the agenda currently.

P.S. Left and Right are artificial illusions

The system has failed and So have we

Chuck Ochelli

http://ochelli.com

I am not a Trump supporter, but I do have questions. This analysis strikes me as similar to much of the rejection of Brexit in suggesting, including in its title, that the election of Trump can be explained as success with getting the votes of xenophobes, racists, and people who like Duck Dynasty. Thus, it seems oversimplified, even though detailed and valuable in its historical perspective.

My question: Are there any other factors explaining Trump’s election? Was there anything good about it? Would we rather have Hillary Clinton?

“Was there anything good about [Trump becoming Prez]?”

Yes, as I’ve repeatedly written for the last year or so, Trump is generally fairly decent on the following two issues:

1.) He does not demonize Putin nor does he vilify the Russian people or the gov’t policies coming out of Moscow. Trump is to be applauded for this courageous stance. Of course the entire political establishment along with virtually every sector of the mass media roundly condemn him for being a “Putin Puppet” or “Moscow Stooge”.

2.) On many occasions Trump’s stated his opposition to the “free trade” agreements (read: investor rights agreements) that have led to outsourcing and job offshoring over the last 30 years which has in turn has led to the absolute decimation of once relatively prosperous cities and towns, especially in the heartland. He’s criticized the runaway of America’s manufacturing sector.

So, yes, there are a couple of good things about Trump’s election. It’s also noteworthy that he denounced the Iraq war, in front of a GOP debate audience no less! Killary was a staunch Iraq war supporter and is terrible on the aforementioned two crucial issues.

But alas, Trump comes will boatloads of the bad: he’s essentially a xenophobe and his penchant for mouthing police-state rhetoric borders on covert racism; people who are honest with themselves know exactly who he’s pandering to and who he’s attempting to demonize. He’s also an Ayn Randian as it comes to regulating for the betterment of consumers, workers, and the environment, and those enrolled in our much maligned public schools.

Given the above, I went with Jill Stein.

And Jill Stein jumped into her own pantsuit and went to bat for Hillary and Soros. Bravo!

I’m not sure of this. Stein has been articulate and honest to an admirable degree, so I tend to think she means what she says. Her stated objective was to test the voting system in particular states, which were the most vulnerable. She said in effect that we must be able to trust the voting systems in order for us to attempt democracy. Naturally, her effort was both appropriated and demonized. I too voted for Stein.

I thought Stein the best candidate (though I voted for Trump as the major alternative to the harpy, who threatened war with Russia) but she jumped the shark when she took the Soros shilling and spearheaded the phony recount effort which, if carried through, could have shown that fraud increased the harpy’s vote in Wayne County, Michigan. I agree again with Mr. Hunkins (which I usually do), that the two key issues, sovereignty v. corporate “trade agreements” and war with Russia were serious issues and that is why I voted for the nominal righty for the first time ever because on the key issues, his was the less dangerous position. I think the issues brought up by Sottile are overblown based on these two key issues mentioned here.

I also think that Willie Horton is more important as the proximate cause of the Clintonian hostile takeover of the Democratic party which could only succeed after the destruction of Dukakis (duly mentioned in the main Sottile article.) What Sottile fails to really realize is that the Clintons themselves were the direct product of Willie Horton but used phony identity politics to mask this fact. Now, with the mainstream democrats clamoring to attack Russia and blame it for their defeat, they have shown themselves to be the real face of yankee fascism at the present time. It has infected many who were immune up to this time and taints all of those who drink this jonestown style kool-aid now being presented, including formerly reliable sources such as Democracy Now, which has reported favorably on yankee-backed terrorists in Syria.

he’s an Ayn Randian?????

ugghhhhhhh

if correct, that’s pretty disturbing…

I’ve never read her stuff but saw her interviews and I think she was mentally disturbed. Her world view was bizarre.

I believe there are other, more significant forces in electing Trump including a gathering rage of many American people over how they have been treated, particularly over the last 16 years. The current authority’s efforts to bamboozle the election indicate how much they’re underestimating the public. Activity such as happening in this forum indicates a form of democracy not yet shut down. Out of our current state of hysteria and dishevelment we might even develop some real power one day.

I agree with the sentiment of your first paragraph. I think the article’s analysis is more relevant to explaining Trump’s success in the Republican primary than to explaining his success with the Electoral College. Given the closeness of the election, an appeal to racism is one of a handful of what we could regard as individually decisive factors … along with sexism, corporate cronyism in the Democratic Party leadership, and free media coverage of Trump that legitimized him in the minds of many voters who (I think) would have readily responded to media cues to dismiss his candidacy. (Hey, it worked with Bernie Sanders, who seems to be getting more media coverage now than he did when he was seeking the Democratic nomination).

I regard the “drain the swamp” rhetoric and opposition to globalist trade deals as positive aspects of Trump’s campaign, but my skepticism during the campaign—my suspicion that Trump merely says what’s in his personal interest without intention to follow through—seems justified given his cabinet nominees, many of which strike me as changing the swamp’s water rather than its removal.

Thank you JP Sottile and thanks again to Robert Parry for publishing Mr Sottile’s critically important piece reminding us of the ugly undercurrents driving presidential elections.

I am proud to say that I rejected the hateful dog whistle undercurrents – in both domestic and foreign rhetoric in this past election, supporting Bernie Sanders in the primary and Gary Johnson in the general.

I am grateful to Mr Sotille because I cannot shake my disgust with either the Republican or Democratic parties. I became aware of the ugly undercurrents when George H W Bush used Willie Horton to beat Dukakis and believe to this day that there was never a “softer gentler” Republican Party or any real 1000 points of light. No one in the Republican Party ever repudiated the ugliness of the shameful Willie Horton tactics and therefore they remain as a bedrock of thinking in that Party. Similarly I was disgusted by Bill Clinton’s 3 strikes and you’re out; don’t ask don’t tell; for profit prisons, welfare reform bill and all the ugly rhetoric that went with it and that was blessed/accepted by Mrs Clinton. Add to that the irresponsible, unsustainable, ruthless.financial deregulation and predatory trade deals that robbed working Americans.

Mr Sottile covered the whole sordid history of scapegoating vulnerable people for political gain. It can’t be brushed under the rug. I know I can’t forget it.

And one of the reasons I supported Bernie Sanders is that he spoke up for vulnerable people and appreciated BLM and Native Americans and immigrants and refused to demonize the easy Cold War targets like Cuba and Nicaragua that Hillary Clinton scapegoated Bernie on in the Miami primary debate.

I was glad to be able to read this piece that covered the sordid political scapegoating mess. Most politicians at the national level have been too weak and scared to stand up for economic and social justice for working people and the most vulnerable among us. Instead they pander to the most powerful even if that means aligning with unsustainable domestic and foreign policies like bad trade deals or endless wars and fail to deal with climate change.

Courage to do the right thing is rare.

Russ Feingold’s votes against the patriot act and the Iraq war come to mind.

Great essay J.P. Sottile. Should be read by every gullible American.

Thanks for calling attention to the horrible acts of Lee Atwater, who showed us how the conservatives will always bring a gun to a political knife fight.

Donald Trump by his own words sounds like a man who thinks in terms of ethnicity and race, than rather by social class and gentry instead. Although he certainly knows there is a difference between the haves and the have nots, he still paints race differences with a broad brush. Trump also knows how to whip up his rhetoric for those willing to listen. Like Atwater he uses the race card to his political,advantage. What remains to be seen, is just how far will he be willing to go with his rhetorical proclamations. I’m hoping that NYC liberal peeps through enough to keep matters civil, and that his bite isn’t nearly as bad as his bark. We don’t need race riots, we need unity.

Am empire in decline.

Stevie Stevie Stevie: 1. People do NOT owe our “support to the new president”. You talk as if we live in a nation headed by a KING–we don’t. Your continued parroting of DISCREDITED BIRTHISM makes every other word you write have NO CREIDIBILITY AT ALL. You are make a FALSE claim that President Obama was not born in the U.S.–he was in 1961 in HAWAII WHICH BECAME A STATE IN 1959.. I’m a progressive/Leftist with many disappointments about Obama’s 8 years–but, fact-free Trump voters only want to take us backwards to 1950 or 1920. Please read mroe & post less …or go somewhere else./

Lydia Lydia twice insidia Oh then why are you supporting that poor excuse for a president Obama? and as for the Birther business what is he hiding that you refuse to see the certificate produced is a fraud and that is a fact proven by independent sources in two different countries and by two investigative sources inside the country the question is not so much where he was born but why he perpetuated this fraud on the American Public. As for tyranny the man is currently setting up to run another four years by starting a Nuclear war, throwing out Russian diplomats, sending troops to Russia’s borders not to mention throwing Israel under the bus, and signing the NDAA yet again which puts all the power in the hands of corrupt bureaucrats and now eviscerating the only remaining amendment to the COnstitution freedom of speech. and no Trump is not trying to take us backwards he’s trying to remove the barriers that keep us from moving forwards, barriers that Global Corporations put there and your precious Obama and Hillary are pushing for more why for lucrative positions in the New World Order.

There’s no point in trying to analyse too deeply a situation where neither candidate or party offfered an attractive – or different enough – alternative. It was more a ‘close your eyes and stick a pin in’ election than anything, where voters knew the only winners would be the 1%.

The whole ‘get tough on crime’ rhetoric coming from virtually every single politician for the last 40+ years is so disingenuous and misleading that it’s dismaying beyond belief.

Most social problems ultimately stem from a fouled up and inequitable politico-economic system. It all goes back to Marx, yes, Marx. Probably the greatest thinker the world has ever known. Of course one must ignore the mischaracterizations of him and the constant socialization one has endured over Marx which have been so overwhelmingly present in all discourses for the last 150 years.

Thriving towns and cities that are now mired in poverty, violent crime, un and underemployment, blight, and drug salesmen on every other corner would’ve been much better off under Scandinavian style socialism, or even Cuban style socialism, rather than the extreme capitalism that’s been rammed down everyone’s throats complete with NAFTA-TPP, a stagnating minimum wage, a Fed that WANTS and DESIRES a certain level of permanent unemployment, for profit health insurers and a big Pharma that are essentially oligopolies, a military budget that’s sick and absurd, and a consumer ethos that says ‘get all you can get’ and screw the other guy.

Hopelessness and despair prevail when people come to the realization that tomorrow holds absolutely no promises and possibly much to fear.

Well said, Drew.

Thanks for the kind words Mr. Bodden.

The author of this article, apparently, is (1) unaware of FBI statistics which document that from 1960 thru 2014, 80% of white women raped and murdered in the USA were victims of African-American criminals according to Pat Buchanan, OR (2) chose to ignore Pat Buchanan’s quotation on TV.

Pat Buchanan is NOT a credible source about much of anything–especially about people of color, women or LGBT community. He’s a backwards racist & sexist who denigrates everyone EXCEPT WHITE CHRISTIAN MEN.

The criticism of both Bush senior and Trump is, in my view, correct, but, as the text points out, Bill Clinton fits in, as well. In addition to his “tough on crime” rethoric (including the first lady’s remarks about “superpredators” that have to be brought to heel) that also has been interpreted by many as having racist undertones and the strategic public attack on Sister Souljah, Clinton’s demonstrative attendence at the execution of Ricky Ray Rector in Arkansas during the campaign could be mentioned.

There is also criticism about racist undertones in Hillary Clinton’s 2008 campaign, which is, in my view, not completely unfounded. A picture of Obama in a traditional garb was given to Druge reports – according to Drudge report, it was from the Clinton campaign, but this is disputed. In any case, a Clinton surrogate talked about “his native clothing, in the clothing of his country”. Hillary Clinton bragged about her appeal to white people (http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/politics/election2008/2008-05-07-clintoninterview_N.htm). The Clinton campaign did not support the birther theory as fully as Donald Trump, but there were statements about Obama’s alleged “lack of American roots” from Mark Penn, Hillary Clinton’s chief strategist, and birther claims went around in Clinton’s campaign. Some of her statements were – probably deliberately – unclear (“he is not a Muslim, as far as I know”).

Of course, like most of what is mentioned in the article, this is not wholly unambiguous racism, but it is very plausible that the Clintons used such dog whistles deliberately.

Quantitatively, it is probably fair to say that Donald Trump went further in these respects, especially as far as immigration is concerned, but Hillary Clinton was hardly a credible representative of steadfast anti-racist principles. She was the lesser evil in that respect, but using this as one of the main themes of her campaign was probably seen as hypocritical by many people given her own history.

He didn’t say they were “raping American women.” He said there were rapists among them. And according to the Obama admin., 80% of the girls and young women who make it across the border have been raped. Ergo, he was perfectly accurate.

Seriously, after reading this entire article (I assume), replete with the effects of intentional “dog whistles” and innuendo and you take Trump’s remark about rapists literally. Mind-boggling…

“He said there were rapists among them.” No, he didn’t. He said “They’re rapists.” Too fine a point? Think about it.

RE: “80% of the girls and young women who make it across the border have been raped” ~ Brandon Simmons

MY REPLY: I would venture to say that many of those rapes were a consequence (at least indirectly) of U.S. foreign policy. Consider the coup in Honduras, for instance. And the drug war(s) in Mexico.