Mythology about the rightness of dropping two atomic bombs on Japan is relevant to today’s “modernization” of the U.S. nuclear arsenal and the revving up of a new Cold War with Russia, says ex-Pentagon military analyst Chuck Spinney.

By Chuck Spinney

With the passage of time, the decision to drop the atomic bombs on Hiroshima (a uranium bomb) and Nagasaki (a plutonium bomb) in August of 1945 has become more controversial among historians but not in the public mind. Was the destruction of these two low priority targets necessary to end the war with the Japan?

In 1945 and thereafter, beginning with the Truman Administration, politicians and milcrats convinced the public that bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki ended the war quickly and thereby saved American and Japanese lives. Against the background of the brutality and racism of the Pacific War — and especially the just completed battles of Okinawa and Iwo Jima, and the overwhelming psychological effects of the Kamikazes — this justification was easy to believe by those troops designated for the invasion of Japan as well as by a public anxious to end the war.

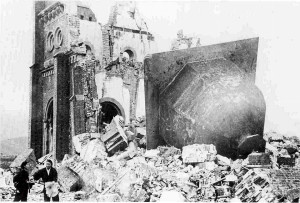

The ruins of the Urakami Christian church in Nagasaki, Japan, as shown in a photograph dated Jan. 7, 1946.

It is hard to overestimate the immediate and lasting appeal of the government’s line to people of all political persuasions: One of my dearest friends, for example, was an anti-tank gunner in the 95th Infantry Division during WWII. While in Germany in 1945, he was notified that he would be redeploying to the Pacific for the invasion of Japan.

My friend was an extreme liberal with a WWII enlisted GI’s contempt for the conduct of war; he believed the military leadership was incompetent; and that carried over to his vehement opposition to the Vietnam War. But 50 years later he still vociferously defended the decision to drop the atomic bombs. His reasoning was simple and heartfelt and honest: he had enough of fighting the Germans and wanted to go home and be done with the madness.

And this belief has lingered through the years, largely unquestioned. But the story of the decision to drop the bomb is far more complicated than this simple argument suggests. One of the world’s leading historians of President Harry Truman’s decision to drop the bomb, Gar Alperovitz, recently sat down with journalist Andrew Cockburn to discuss these complexities (attached below).

The question addressed by Alperovitz and Cockburn is more than an idle historical curiosity. Alperovitz hints as much in the last pregnant paragraph of his interview. President Obama’s administration is planting the seed money for an across-the-board-modernization of nuclear weapons, delivery systems, and support systems that will cost at least a trillion dollars (more likely $2 trillion to $3 trillion, IMO) over the next 15-30 years.

Workers at the Hanford nuclear facility work to transfer highly radioactive material into storage containers to be moved out of a facility near the Columbia River. (Photo credit: hanford.gov)

While its details are shrouded in secrecy, public information is oozing out (e.g. see this link). Present information now suggests this program includes: a new ballistic missile launching submarine; a new strategic bomber; a new land-based intercontinental missile; a new air-launched cruise missile; modernization of and adding precision guidance to the B-61 “dial-a-yield” gravity bomb; modernization of strategic ballistic missile warheads; upgrades to the sea launched ballistic missiles; a massive upgrade to the surveillance, reconnaissance, command, control, and communications systems needed to manage nuclear warfighting; continuation and upgrades to ballistic missile defense systems (rationale: gotta have a “shield” to protect the aforementioned “swords”); modernization of the nuclear weapons laboratory infrastructure; and the increasingly demanding problem of nuclear weapons facilities cleanup (e.g. Hanford).

Given the highly evolved nature of the domestic politics driving defense spending (i.e., the domestic operations of the Military-Industrial-Congressional Complex (I described this in “The Domestic Roots of Perpetual War”), history shows the golden cornucopia of this nuc “bow wave” or programs will quickly evolve into an unstoppable tsunami of front-loaded and politically engineered contracts and subcontracts that will grow over time to overwhelm and paralyze future Presidents and Congresses for the next 20-30 years.

This kind of budget time bomb has happened at least twice before in the non-nuclear part of the defense budget: The first began when the Nixon-Ford Administration planted the seeds of defense budget hysteria by starting a bow wave of new modernization programs, financed in the short term by readiness and force structure reductions in early-to-mid 1970s. These reductions led to budget pressures that exploded in the late 1970s and 1980s when President Jimmy Carter began growing the defense budget and President Ronald Reagan accelerated that growth.

The game repeated itself in the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, when Presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton planted the seeds for future budget growth that would metastasize in the late 1990s. That bow wave was subsequently power-boosted and masked somewhat by hysteria accompanying 9/11, but it used the same formula of cutting readiness and force structure in the short term to finance the planting of the bow wave of modernization programs.

Near the ceasefire line between North and South Korea, President Barack Obama uses binoculars to view the DMZ from Camp Bonifas, March 25, 2012. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

And now, history is repeating itself for a third time. This can be seen in the spate of recent hysterical and misbegotten reports (e.g., typical example) about how the relatively modest budget cutbacks from 2010 in the Pentagon’s “base budget” have caused today’s modernization crises, readiness shortfalls, etc.

Now add the full-scale nuclear tsunami to this limited description of the Obama bow wave and the pressure to grow future budgets justified by a new cold war will become unstoppable.

The only way such a modernization program can be justified is to concoct some kind of 21st Century nuclear warfighting scenario and to use the rubric of a new Cold War against a nuclear-armed competitor — read Russia or China or both — to terrorize the public into paying the bill.

Which brings us back to the logic of bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Attached beneath the end notes is Cockburn’s short but incisive interview with Alperovitz. (Caveat: Andrew Cockburn is a close friend of 35 years, so I am biased.)

Chuck Spinney is a former military analyst for the Pentagon who was famous for the “Spinney Report,” which criticized the Pentagon’s wasteful pursuit of costly and complex weapons systems.

Unjust Cause

Historian Gar Alperovitz on the decision to bomb Hiroshima and Nagasaki

By Andrew Cockburn, Harpers, 25 May 2016

http://harpers.org/blog/2016/05/unjust-cause/

President Obama is about to visit the Japanese city of Hiroshima, where on August 6, 1945, the United States dropped an atomic bomb that killed 140,000 people. Earlier this month, Deputy National Security Advisor Ben Rhodes wrote on Medium.com that “the President will shine a spotlight on the tremendous and devastating human toll of war.” But the White House has also made clear that the president has no intention of apologizing. Seventy years after World War II, it seems the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki are still a matter for evasion, justified by U.S. officials as the only way to end the war and save American lives. If Obama sticks to this script, his speech won’t amount to much more than Donald Rumsfeld’s “stuff happens.” To fill in Obama’s preannounced omissions, I turned to the historian Gar Alperovitz. His 1995 book The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb and the Architecture of An American Myth is the most definitive account we are likely to see of why Hiroshima was destroyed, and how an official history justifying that decision was subsequently crafted and promulgated by the national security establishment. As he explained, the bomb not only failed to save Americans lives, it might actually have caused the needless deaths of thousands of U.S. servicemen.

Let’s start with the basic question: was it necessary to drop the bomb on Hiroshima in order to compel Japanese surrender and thereby save American lives?

Absolutely not. At least, every bit of evidence we have strongly indicates not only that it was unnecessary, but that it was known at the time to be unnecessary. That was the opinion of top intelligence officials and top military leaders. There was intelligence, beginning in April of 1945 and reaffirmed month after month right up to the Hiroshima bombing, that the war would end when the Russians entered [and that] the Japanese would surrender so long as the emperor was retained, at least in an honorary role. The U.S. military had already decided [it wanted] to keep the emperor because they wanted to use him after the war to control Japan.

Virtually all the major military figures are now on record publicly, most of them almost immediately after the war, which is kind of amazing when you think about it, saying the bombing was totally unnecessary. Eisenhower said it on a number of occasions. The chairman of the Joint Chiefs said it—that was Admiral Leahy, who was also chief of staff to the president. Curtis LeMay, who was in charge of the conventional bombing of Japan, [also said it]. They’re all public statements. It’s remarkable that the top military leaders would go public, challenging the president’s decision within weeks after the war, some within months. Really, when you even think about it, can you imagine it today? It’s almost impossible to think of it.

Had the United States ever wanted the Russians to come in?

Here’s what I think happened. Not knowing whether the bomb would work or not, the top U.S. leaders were advised early on that the Russian declaration of war, combined with assurances that the emperor could stay on in some titular role without power, would end the war. That’s why at Yalta [the February 1945 summit between Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill] we desperately begged the Russians to come in, and they agreed to come in three months after the German war ended.

U.S. intelligence early on had said this would end the war, which is why we sought their involvement before the bomb was tested. After the bomb was tested, the United States was desperately trying to get the war over before they came in.

Is it possible that the U.S. leadership avoided actions that might have brought about surrender, to keep the whole thing going so that they would have an excuse to use the bomb?

Now you’ve put your finger on the most delicate of all questions. We cannot prove that. But we do know that the advice to the president by virtually the entire top echelon of both military and political leaders was to give assurances to the Japanese—that would likely bring about a surrender earlier in the summer of 1945, after the April intelligence reports.

Had they given those terms at that time, as many of the top leaders suggested—Under Secretary of State [Joseph] Grew for instance, and Secretary of War [Henry] Stimson as well—the war might very well have ended earlier, even before the Russians came in.

The allied leaders meeting at Potsdam in late July issued the Potsdam Declaration laying the surrender terms for the Japanese. In your book, you discuss an attempt to include the necessary assurances about preserving the emperor in the declaration. What happened?

As originally written, paragraph twelve of the Potsdam Declaration essentially assured the Japanese that the emperor would not be taken off of his throne, and [would] be kept on in some titular role like the king or queen of England but with no power. It was a recommendation of everyone in the top government, with the exception of Jimmy Byrnes. Byrnes was the chief advisor to the president on this matter, and he was secretary of state. There’s no doubt that he controlled the basic decision-making on it. He was also the president’s personal representative on the interim committee, which considered how, not whether, to use the bomb. He was the man who was directly, in this case, in charge. They all thought the war would end once that was stated, and they knew the war would continue if you took out paragraph twelve, and Jimmy Byrnes took it out, with the president’s approval.

So that was a deliberate effort to prolong the war?

I think that’s true, but you can’t prove that. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, facing a blockage by Byrnes, found a way to get the British Chiefs of Staff to go to Churchill to go around Byrnes to Truman to try to get him to put the paragraph back in, which Churchill in fact did. Truman did not yield. He followed Byrnes’ advice. A remarkable moment.

What was the justification for Nagasaki?

Well, the claim was that it was an automatic decision. The decision had been made to use them when they’re ready. I think the scientists, and then also the military, Groves in particular, wanted to test the second one.

There is another reason I think was probably involved. The Red Army had entered Manchuria on August 8, and Nagasaki was bombed on August 9.The entire focus of top decision-making, which means Jimmy Byrnes advising the president, at this point in time . . . we’re now past whether or not to use the bomb . . . was whether you could end the war as fast as possible, as the Red Army was advancing in Manchuria. The linkage logically between that and “Is that why Nagasaki went forward?” or, rather, “why it was not aborted” is impossible to make with the existing documents, but there’s no doubt that the feeling and the mood in the top decision-makers was on “How do we end this damn thing as fast as we can?” That’s from a context in which the decision to hit Nagasaki either was made, or rather, not questioned.

The official line, that we had to do it, the bomb saved lives, the Japanese would have fought to the last man, and so forth, set in hard and fast fairly quickly. How do you account for that?

Harper’s Magazine played a major role. They published what was basically a dishonest piece by the former secretary of war, Henry Stimson. There was in fact mounting criticism after the war, started by the conservatives, not by the liberals, who defended Truman, which was then opened up by the military, and then some of the scientists, and then some of the religious leaders, and then the article in the New Yorker, John Hersey’s “Hiroshima.”

There was sufficient criticism building in 1946 that the leadership thought it had to be stopped, and so they rolled former Secretary of War Stimson out to do a strong defense of it. It was actually written by McGeorge Bundy [later National Security Adviser in the Vietnam years], and they got Harper’s Magazine to publish it [in February of 1947]. The article became a major report all over the country, and it became the basis of reporting in the newspapers and radio at that time. I think it’s correct to say that it shut down criticism for roughly two decades.

Well, we can consider this interview an act of expiation. Was it important for U.S. foreign policy going forward to convince the country and the world we had not done a bad thing but a good thing by ending the war and saving lives?

Yes, on two levels. Hiroshima and Nagasaki were not military targets. That’s why they had not been attacked, because they were so low in the priority list. So who was there? There were a few small military installations.The young men were at war, but who was left behind? Minimally, about 300,000 people—predominantly children, women, and old people—who were unnecessarily destroyed.

It’s an extraordinary moral challenge to the whole position of the United States and to the decision-makers who made those decisions. If you don’t justify that decision somehow, you really are open to extreme criticism, and justly and rightly so.

If Obama is not going to apologize for the bomb at Hiroshima, what should he say?

It would be good if the president were to move beyond words to action while in the city. A good start would be to announce a decision to halt the $1 trillion buildup of next-generation nuclear weapons and delivery systems. And he might call upon Russia and other nuclear nations to join in the good-faith negotiations required by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty to radically reduce nuclear arsenals.

How insane are humans to even imagine creating weapons that will destroy the whole world, as if it is some status symbol to be a nuclear nation of nutcases. I am embarrassed to belong to my species . To consider that we dropped atomic bombs on civillians and have to actually think twice about apologizing? Really? There’s no question it was wrong! I am very sorry. My ancestors weren’t here yet, but I am still very sorry for the psychotic behavior of my country. And now we’re forever paranoid someone will do it back to us. But no worries. The stupid war games we play with NATO or to prepare for imaginary drama are enough to kill is all from radioactivity without WW3. Atoms for peace? What a joke that turned out to be! Only when the human race is obliterated and resting in peace will the nuke gang be satisfied. Such a waste of one’s scientific mind to be employed by the nuclear industry of death

These Two were the eptome of the definition” Terrorist Attack

With respect to the actual article above, and the one or two trillion dollars to be spent on upgrading the US nuclear arsenal — after all, what’s a couple trillion when you’re already in debt for something like 17 trillion — it’s worth repeating for the upteenth time: An empire in decline is at its most dangerous.

The US in decline is like the enraged father and ex-husband, who kills his former wife and children because if he can’t have them, nobody can.

The nuclear EMP weapon is the weapon of choice for WWIII.

I’m a veteran of a pre-Vietnam Army who was truly well trained and totally gung-ho.

I was discharged in 1965, thirty days before my division went to Vietnam Nam. I truly loved (and still do) my “Band of Brothers” and I have become, over time, an “extreme liberal” with a ‘contempt for the conduct of war’ like the enlisted GI Chuck Spiney describes above, with a contempt for incompetent leadership. I also have studied the minority position of an appointed commission, on both the Dresden and Tokyo civilian bombings and I thoroughly agree with that minority.

This article is prescient because it IS the discussion that the American public should have had during the Kennedy Administration and didn’t have because The President was eliminated from having it. The same is true of Martin Luther King, this IS the conversation he wanted and we didn’t have because HE was eliminated.

Nuclear weapons ARE what we now need to eliminate. And this represents yet another betrayal of president Obama to his campaign rhetoric. For shame…

Realist, what you just said about the present is very true. I voted for ‘the Man’ twice myself. Is, he the worst I don’t know, but he is far from being the best, that is a certainty. I believe that the assassination of JFK, was the example used to tell any newly elected presidents, ‘be careful, be very careful to what you do’. In fact, I don’t believe that any president since 11/22/63 has really ruled without the approval of the deep state. One could make a good argument, for how it has always been this way, but I digress.

Our country prides itself on being good at business. If we are such good businessmen, then why can’t we obtain resources by being just that, good business people? No, we feel the need to rob our nations treasures by building huge weapon systems. Systems do big, that if we ever used these weapons to the fullest, there would be nothing left to need any more resources to develop energy, and product for. Think about that for a moment, and how stupid that really is. An intelligent world would have scraped the idea of furthering the nuclear weapon age, back when after we dropped those bombs on Japan. Yet, here we are some seventy years later, planting missile sites everywhere we can. We are not good business people, as much as we have become terrifying thugs, who demand that we rule the world exclusively. Realist, you are 100% correct, it is ‘madness’.

Thanks for the comment, Joe, and for all of the other articulate on-point comments you have regularly made at this site. Not only the authors, but numerous other commentators have made this place essential reading every day.

Thanks, I get a lot out of your comments, as well. Yes, this site has some pretty good commenters, even if we don’t always agree in total.

Yes, weapons so big and destructive (capable of turning Earth into a Martian landscape), that they can’t be used in any rational context, not even as a threat to bully someone into doing what you want them to do. We’ve already been through all of these arguments, leading to a Cold War and S.A.L.T. talks. There is some powerful Faction within human society fanatically committed to militant Geopolitics & Empire-Building who will stop at nothing to prevent other Empire Builders from doing the same as them, AND absolutely committed to stopping the rest of Society from interfering with their “Great Game”. Most folks already know war was obsoleted by the Atom Bomb, that the only rational role for the military was to function as U.N “Blue Helmets” to stop any warring Factions; to “Cease & desist” and come to the U.N.’s Treaty Table. Most reasons for any Factional strife can be defused with Development & Improvement Programs (“New Deal/Marshall Plan” time). 1, 2, 3 trillion dollars to be wasted on useless WMDs? Godalmightydamn, the Army Corps of Engineers turned in a “report card” YEARS ago, on the Nation’s infrastructure…in need of at least 5 Trillion $ in upgrades & modernization (can be funded with totally fiat “Greenback/Credit”, if Fed is nationalized…no taxes needed for the Program…or tax Wall Street 1% sales tax for a cool trillion a year). Anyway this is a much more useful expenditure of Credit/Capital & Labor, than on useless WMD’s and a useless Force to guard, & train with, them. Also The BRICS Nations, especially Russia & China, are EXACTLY of this same mindset, what with their “Silk Road” development corridor Program (THEIR version of New Deal/Marshall Plan). We should be JOINING with them, NOT figuring out how to obliterate them (which would only obliterate us too…then we wouldn’t have to go to Mars to see a Martian landscape).

Oh yeah Joe. I voted for him twice too. First time hoped to be getting FDR/JFK (turned out to be Coolidge/Hoover, riding in on the shoulders of “those savvy businessmen” of W.S.). I voted for him the second time because HE had the impeachable record, and could be IMMEDIATELY punished for his savagery; Romney did not (didn’t want to suffer 4 years of HIS savagery). Turned out the Republicans weren’t interested in throwing out Mr. O (one of their own, turns out).

Brad, I wish I had written what you wrote here.

This “modernisation” program for all our nuclear weaponry and delivery systems at such a humongous price is frankly madness. Just who do we intend to fight, invading space aliens? The only two countries that could possibly afford to match us a nickel on a dollar, both in terms of wealth and talent, are Russia and China. And, believe me, from all I can see neither has any intention of mixing it up mano a mano with the United States of Idiocracy on a nuclear playing field–or even in a conventional war in which we’d still outgun them 10-to-1 and outflank them on their every border with our 1,000 bases around the globe. No, we don’t intend to “defend” ourselves against those countries, we intend to vanquish them, which is totally loathsome, as those people are simply human beings like ourselves trying to survive and prosper if possible. But WE view the totality of human society as a zero sum game: any progress THEY make is viewed as detracting from what WE want–which is fucking everything. What a sane leader, unlike warmongering Barack Obama, who is clearly mad, would do is MAKE DEALS, i.e., sign treaties pledging our word and our cooperation towards universal world peace with those two countries… and other countries as well. That would sure as hell save us much more than the trillion (or 3 trillion) dollars that Obomber proposes for us to squander. Do that and you can pretty much kiss off all of social programs, education of our young, affordable health care, and most of the infrastructure already in disrepair–to say nothing of preserving the Earth’s environment and staving off cataclysmic climate change. Obomber FORFEITS everything worthwhile in life with this decision (and also with the “free trade deals” he intends to shove down our throats). The man has easily qualified as the WORST president in the history of this nation–and I voted for the [expletive deleted] twice.

Make that the worst leader in all of the world’s history…. and I don’t exclude anyone…. anyone.

@Harold……..And the Japanese people were all happy and supportive, willingly believing they were a ‘master race’.

Exactly the same as the American people who went along with dropping more bombs on North Vietnam, than were dropped in all of WWII, willing to believe that we were the master race.

Sorry Harold. You argument cannot hold the moral high ground

Respectfully

Dennis

The Japanese Empire launched two brutal wars of aggression, China and the Pacific. They killed millions of Chinese, including raping tens of thousands of women and murdered hundreds of thousands of civilians in Nanjing in a two week orgy of violence. They starved, tortured and executed their POW’s. They forced thousands of young women and girls into sex slavery. They conducted biological warfare experiments on civilians and POW’s. And the Japanese people were all happy and supportive, willingly believing they were a ‘master race’.

So no apologies and no sympathy. When you sow the wind, you reap the whirlwind…

Harold,

As my mother used to say..”Two wrongs don’t make a right”.

I don’t care what our “enemies” did.

That is no excuse for us killing their civilian population.

All these aerial bombing of civilians in modern wars were futile.

Achieved very little. And was immoral.

We are supposed to be the moral, and righteous nation, with God on our side.

My “God” would not approve of murdering innocent civilians….what did they do to us?

No?

He is simply pointing out that even innocent Japanese civilians would eagerly take the spoils of victory, as would innocent Germans or Americans, and if you get whacked don’t squawk “war crime!!”. A lesson we Americans should heed, but won’t.

Harold,

A little history for you:

In the 1930’s Imperial Japan invaded China and the two locked into war.

Tragic as it was, it was their business.

But America made it its business.

The US had no defense agreement with China but nevertheless proceeded to impose more and more measures against Japan unless it got out of China.

Then FDR imposed one fateful measure on Japan – cutoff of oil and trade between Japan and its trading partners in SE Asia, most important of which were Malaysia and Indonesia. FDR made it clear that its forces stationed in its colony the Philippines would enforce the trade blockage.

This was a de facto declaration of war by America on Japan.

While Imperial Japan have invaded China, it had not touched a single interest of America.

So why the de facto war on Japan?

Answer, to get Japan to attack the British naval base in Singapore, thus bringing the full Axis into war.

So who sowed the wind?

Maybe I have this all wrong?

Yes you do have it wrong. I do not judge Japan’s expansionist aggression, they were acting in their perceived self-interest. History shows it started with Meiji Restoration(approx. 1870) kicked off with an invasion of the Ainu State Of Hokkaido. 1879, it was Okinawa’s turn. 1895, attack on China and seizure of Taiwan. 1910, Korea’s turn(and Korean’s have not forgotten). WWI, seizure of German Pacific island colonies. 1920’s, harassment of China, and 1931 invasion of Manchuria, China, then 1937 the rest of China. Japan armed up with the intention of kicking USA butt, they were not goaded into war, hubris caused them to miscalculate very, very badly.

David Smith, I recommend you read “Imperial Cruise” by James Bradley. The story of Japan’s role in WW2 started at the time of Teddie Roosevelt. The military historians will recount the battle at Port Arthur, the battle of Tsushima Straits, and the US goading of Japan into attacks on Korea and China. The Japanese viewed the US as allies – as it turned out, very untrustworthy allies. The war did not start with Pearl Harbor – except in US high school history classes. The Koreans also viewed the US as an ally, at least until the US supported Japan in their attack against the mainland. Teddie Roosevelt considered the Japanese to be the “Aryans” of Asia – who should fulfill their destiny by taking over China and Manchuria (Go west young man).

As many military historians have pointed out, the two nuclear bombs were unnecessary and served no military purpose. If Truman did not know this, it would be because he was unaware of what his subordinates were doing in his name.

Japanese actions no different than those of European imperialists, and America too after 1898.

Nonsense. The U.S was against Japan before it joined the Axis. The conclusion is that Roosevelt was opposed to Japanese aggression and war crimes in China.

Hello Harold,

Does this sowing and reaping also include the US? If not, then why not?

I agree- the late George Orwell once observed that there are some ideas so nonsensical that only an intellectual could take them seriously. Case in point: the canard that Truman approved the atom bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki NOT to end the war and save American lives but to”intimidate the Soviet Union”.

Whenever i hear this canard, I always want to ask: “intimidate the Soviet Union-then ruled by Stalin- from doing what? Forcibly Sovietizing Eastern Europe? Launching first the Berlin Blockade(which Truman countered with the Airlift) and then conniving at Kim Il Sung;s attack on South Korea in June 1950?”

Unlike Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon, who were notorious liars(Truman once observed publicly of “Tricky Dicky”- “he does not lie simply because it is in his interests to do- he lies because it is in his very nature to do so!”) had and has a reputation for integrity, if he said that “nuking” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was necessary to save American lives, then I for one believe him. It is also worth noting that NO serious student of history or biographer of Truman(such as the most recent one, “Truman” by David McCullough, Simon and Schuster, 1992) takes this claim seriously.

For people who like to live in an alternate reality I’m including two more links to Gar Alperovitz.

http://www.thenation.com/article/why-the-us-really-bombed-hiroshima/

hXXp://www.csmonitor.com/1992/0806/06191.html

For those who prefer the real world, there are plenty of fine history books available about the realities of the day.

To each his own.

To Chuck Spinney: I wonder about the sanity of our Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

I wonder about the sanity of our Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

The problem is more likely a question of values bereft of a moral compass.