Congress continues to shirk its duty to consider a new authorization of force for U.S. military conflicts in the Mideast that are on shaky legal grounds and deserve a thorough rethinking, writes ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar.

By Paul R. Pillar

The request by a U.S. Army captain to a federal court for a declaratory judgment about his constitutional duties regarding going to war is the latest reminder of the unsatisfactory situation in which the United States is engaged in military operations in multiple overseas locales without any authorization other than a couple of outdated and obsolete Congressional resolutions whose relevance is questionable at best.

Of the many ways in which the U.S. Congress has fallen down on the job, this is one of the more important ones. There are several reasons that Congress should take up without further delay the question of an authorization for the use of military force (AUMF). Getting out of the legal netherworld in which current U.S. military operations exist is one of those reasons.

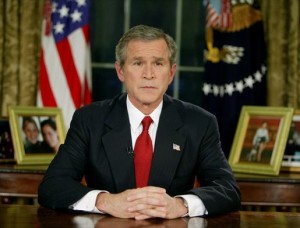

President Barack Obama delivers an address to the nation on the U.S. Counterterrorism strategy to combat the Islamic State, in the White House, Sept. 10, 2014. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

Another reason is that Congress is, along with the Executive Branch, a co-equal policy-making arm of government. Important dimensions of war and peace should reflect the best judgment of the people’s representatives in Congress, rather than that branch being merely a kibitzer and critic of what the administration does.

It is bad enough that on countless domestic issues Congress has wavered between doing nothing and outright obstruction. It is worse still that it has not stepped up to the plate on something as consequential as the use of armed force.

Yet another reason is that a Congressional debate can be a vehicle for weighing and examining, publicly and thoroughly, the purported reasons for currently using U.S. military forces abroad, and for setting clear objectives and limits for any continued use. The idea is not only to get an authorizing resolution right, but to get the policy itself right.

A good debate would be an occasion for questioning what have become widely accepted but generally unexamined assumptions underlying much current policy involving military force. A Congressional debate can be such a vehicle, but it won’t necessarily be that, which is where the how as well as the why of Congressional consideration of the subject comes in.

The nation unfortunately has had experience in how not to do it. One such instance was the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution of August 1964, which became used as an authorization for the entire Vietnam War. Congress approved the resolution by overwhelming majorities after just nine hours of debate, only a week after the naval incident that was the peg on which the resolution was hung. Extensive Congressional examination of the Vietnam situation, particularly by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee chaired by J. William Fulbright, would begin only after the United States was deeply mired in the war.

Just as bad was how Congress approached the resolution, enacted in October 2002, authorizing the offensive war in Iraq. This time there was no consideration at all of the resolution in committee — only a cursory floor debate. Republicans were mostly observing party loyalty to their president. Democrats were anxious to get the vote out of the way as quickly as possible to maximize the time between the vote and the elections in November. Political pusillanimity prevailed.

One of the few members to lament this shoddy and rushed performance of Congress’s duty was Sen. Robert Byrd, D-West Virginia, who said on the Senate floor a few weeks before the invasion, “This chamber is for the most part ominously, dreadfully silent. You can hear a pin drop. Listen. You can hear a pin drop. There is no discussion. There is no attempt to lay out for the nation the pros and cons of this particular war. There is nothing.”

A proper Congressional consideration today of an authorization for the use of military force would begin with extensive hearings by the foreign affairs and foreign relations committees of each chamber that would examine the most basic questions about U.S. interests and objectives in the countries concerned. Such an examination would subject to questioning from all sides every assumption about what difference the longevity of a particular regime, or the status of a particular group, does or does not make to U.S. interests.

There also would be hearings of the two armed services committees that would explore all relevant questions not only of the immediate effectiveness of different applications of military force but also of the different turns and scenarios to which any one application could lead.

This whole process, including floor debate, of considering a new AUMF could last many weeks. Congress should not rush and sacrifice thoroughness in doing so. The existing resolutions on which current military operations dubiously rest are more than a decade old, and some of the operations themselves have been going on for years.

It has now been over a year since the Obama administration sent to Congress a draft AUMF. That draft is fair game to be picked apart both by those who believe it goes too far and by those who think it is too restrictive. A thorough Congressional consideration of the subject ought to involve lots of picking apart of this document, and maybe even a wholesale substitution for all or parts of it.

At least the administration tried to get things started with a draft. The majority party in both houses of Congress has done nothing. Its members evidently do not want to take responsibility for the consequences of U.S. military operations. It is more comfortable to continue to carp and to criticize, even if much of the criticism is in the direction of wanting still more use of military force. Political pusillanimity still prevails.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University for security studies. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

One of the few members to lament this shoddy and rushed performance of Congress’s duty was Sen. Robert Byrd, D-West Virginia, who said on the Senate floor a few weeks before the invasion, “This chamber is for the most part ominously, dreadfully silent. You can hear a pin drop. Listen. You can hear a pin drop. There is no discussion. There is no attempt to lay out for the nation the pros and cons of this particular war. There is nothing.”

In that speech – Rush to War Ignores U.S. Constitution: Sen. Robert C. Byrd (D-WV) October 5, 2002 – http://www.antiwar.com/orig/byrd1.html – Byrd warned his senate colleagues a vote for war would be in violation of their oaths to the Constitution. 77 senators violated their oaths to the Constitution according to Senator Byrd who was the recognized authority on this document in the senate.

DEBATE?

Paul Pillar should know that “debates” in any real sense

(as in an academic “debate”) do not exist. All the examples

he cites were political, not legal decisions. Any “debate”

in Congress or in the US today would be more than

warranted as Pillar suggests, but in fact totally useless.

They would become part and parcel of the current US

political (“socio-political”?) situation.

Instead a Pillar type “debate” is presented as though

it were a piece of cold scientific research with all the

pros and cons carefully laid out and considered and

the only possible resolution being found. Such is

not the case.

The UN document has relevance but the UN itself

was a product of political bartering from its origin

and before (See Gabriel Kolko, POLITICS OF WAR).

Its rules are used selectively to favor one party

or another. The US expresses shock at the

bombing of hospitals in Syria but has nothing

to say about the bombing of hospitals,ambulances

etc. in Palestine by Israeli (US) forces.

The change at the UN in recent years has not been in

its words such as Article 2(4) but in the increased

skill of other nations to use the UN to their benefit such

as Russia, the SCO nations etc.

Note that more recent invasions and wars have

invariably been before the UN for the sake of

propaganda but action taking place

outside of the UN itself. These include Vietnam,

Iraq, Afghanistan etc. The invasion and destruction

of Libya was done under the aegis of the UN for

“humanitarian” reasons. Russia has often publicly

regretted their error in failing to veto any such actions

which were entirely disingenuous. The Korean War

is another exception since the USSR made the “error”

of leaving the debate, an error that they were never again

to repeat.(This has made Russia a more powerful

nation but like the USA and west not “all-powerful”).

—Peter Loeb, Boston, MA, USA

On one occasion while watching Orrin Hatch and another senator engage in a debate on C-Span, one senator read his point from a paper in front of him. The camera switched to Orrin Hatch who read his rebuttal from the script in front of him. On another occasion Bernie Sanders was citing a list of egregious acts related to economic injustice. The camera switched to Senators Chris Dodd and Tom Harkin who appeared to be enjoying some joke they shared. So much for “the world’s greatest deliberative body.”

Peter Loeb… You are correct with the assertion that the UN can be manipulated but I still believe that it is the best vehicle for the world to create an even playing field and constitute laws that all nations should abide by. It is chilling to hear Victoria Nuland speak about Banki-Moon “midwifing this thing” and that is why I believe that the UN needs to be more fair and not sway one way or the other. Frankly, our western nations, are breaking international law left, right, and centre these days. If we actually abided by international law then most of these wars would not be occurring and Al Qaeda would not have gained a foothold in so many Middle Eastern countries which has also led to ISIS or Daesh. I also believe strongly that all countries should be full members of the International Criminal Court and also accept prosecution if their country is brought before it – personally I believe that George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Tony Blair etc. should be up on charges in the Hague. I just believe overall that we have the vehicles to largely stop wars but they need to be respected and that is the responsibility of people in our governments to accept that they are not above international law and instead are subject to the same rules as the rest of the world. If that occurred, and the UN acted fairly towards all of its’ members, then we would see a dramatic reduction in wars and conflicts on this planet (I believe that UN Charter Article 2(4) also covers coups and covert operations in their illegality).

Peter Loeb… Here is a link to a world map which shows the membership of countries in the International Criminal Court – to be a full member state then a country would have needed to fully ratify the Rome Statute, I believe. Here is how the map breaks down:

1) Green: State Party (fully ratified the Rome Statute)

2) Yellow: Signatory that has not ratified

3) Red: Non-Party, Non-Signatory

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/International_Criminal_Court#/media/File:ICC_member_states.svg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rome_Statute_of_the_International_Criminal_Court

I don’t think the bombing of Syria was illegal, as we did not declare war on it and therefore did not engage in acts of aggression. That being said, I do not believe we should have gone to Iraq or Syria in 2014. I’m glad Trudeau got out of there, but its a pity he’s training the Iraqi troops. Elizabeth May was right – we shouldn’t have gone there. (I indeed first found this site while looking for opposition to the intervention, along with The Nation (although I believe I first heard about it on Wikipedia but forgot), Counterfire, Popular Resistance, and AntiWar.)

Rikhard Ravindra Tanskanen… Of course the bombing of Syria was illegal, at least under international law. The US, Canada, and all the countries of the Coalition do not have permission from the Syrian Government nor did the United Nations, the UN Security Council, sanction the invasion of Syria. It is very clear in the UN Charter, Article 2(4):

“All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.”

Dropping bombs in Syria without the aforementioned conditions breaks the UN Charter by “use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations”. The same could be said about Iraq, which to me was absolutely a war crime which resulted in the deaths of 1/2 Million to 1 Million people. As for Libya, it was sanctioned by the UN, or at least a no-fly zone was. With Libya, NATO went too far and instituted “regime change”, as I believe was the original plan and it also seems to me that many of the “rebels” that we supported in Libya turned out to be Al Qaeda or affiliated to them – “We came, we saw, he died – ha, ha, ha”!

I believe there is a lot of criminality in the Middle East and the War “on” Terror is really a War “of” Terror which was preplanned before 9/11 occurred, the Project for a New American Century, which US 4-star General Wesley Clark spoke about in 2007 that the US had plans to overthrow the governments of 7 countries across the Middle East – Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Iran.

We should not be above international law and if we believe that we are then surely our hypocrisy is showing.

Rikhard Ravindra Tanskanen… one other thing, you said that “we did not declare war on it and therefore did not engage in acts of aggression”. So if another country came to Canada and started dropping bombs in our country – you wouldn’t see that as an “Act of War” or an “Act of Aggression”? C’mon… if someone did to us what we have been doing in the Middle East we surely would see it as an Act of War and certainly we would be fighting the force that were dropping bombs in our country without our permission. I believe that Canada actually had a law, or has a law, that is supposed to prohibit us from going to war without a UN Security Council Resolution unless, of course, Canada is directly attacked. Then John McCain shows up in Halifax and, I believe, did a speech encouraging Canada to ignore that law and join in the bombing of Syria. Sure enough then Harper started the bombing. I think when it comes to Trudeau, I actually believe he realizes what a slippery slope, under international law, bombing in Syria really is and the fact that Canada is a full member of the International Criminal Court where I believe the US is a signatory but has not fully ratified or something to that effect. I truly believe these are wars of aggression by the western world in the Middle East and that the “terrorists” that we are fighting are largely a creation of the US, and the west, and that ISIS along with Al Qaeda are being armed, funded, and trained by our allies such as Turkey, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar.

The absence of Congressional debate in starting the Vietnam and Iraq II wars clearly shows the inability of elected officials obeying party policies to openly and thoroughly debate essential issues in a manner traceable to the public interests, professional analyses, and probable outcomes.

This is why we need a distinct institution to analyze and textually debate the effects of policy options. It must preserve all views of the problems, including unpopular, inconvenient, and “enemy” views. And it must provide for controlled, moderated, systematic textual debate, with well-grounded analyses and criticisms thereof referencing facts and other analyses. By this means the public knowledge of policy options is assembled, with all variant interpretations, for public study and Congressional advice.

I call this the College of Policy Analysis, conducted largely on internet by professionals at universities and other institutions, with public access to analyses and debates. It could be part of the Congressional Research Service (of the Library of Congress) which presently only assembles existing papers upon staff inquiries.

By this means politicians and pundits and citizens in general can learn, ground their statements upon references to credible analyses, and be held to departures from any general consensus of the CPA. Propaganda and foolish blather can be shown to be careless and at variance with such public knowledge.

I am proposing this institution to Senators and would like to hear intelligent commentary. It is already clear that the success of such an institution depends upon its processes to guarantee impartiality in procedures and administration.

I believe more than any countries individual laws that international law should be respected and there should be consequences if you break international law. Look at the UN Charter, I believe Article 2(4):

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations.

This should also mean that all countries that are members of the United Nations should also be full members of the International Criminal Court and subject to prosecution if international law is broken. I am a Canadian and when Canada joined the coalition to drop bombs in Syria, without UN approval, we most certainly broke international law and being that Canada is a full member of the International Criminal Court I also believe that Canada should be put on trial. How can we expect countries around the world to respect international law if we ourselves believe that we are above it. I mean we can prosecute Nazis but not people who lead their countries to break the UN Charter by illegally invading a nation which results in the deaths of hundreds of thousands or millions of people – it’s hypocritical. My overall point is that with international law, and the ICC, we already have the vehicles to largely stop war and it would only take the will of the countries of the world to demand “fair” treatment when it comes to international law and how consequences are handed out if a country breaks it.

I also believe that Article 2(4) of the UN Charter also protects countries from coups or political interference from outside countries – “political independence of any state”.