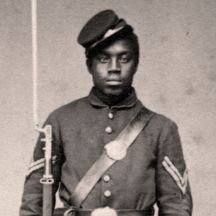

From the Archive: U.S. history is distorted by the prism of race, even the Civil War, which was fought over slavery but then enshrined white heroes when Jim Crow racism quickly asserted itself, a reality relevant to Black History Month and to Chelsea Gilmour’s investigation into the mystery of Camp Casey.

By Chelsea Gilmour (Originally published on Feb. 26, 2015)

As much as Virginia loves its Civil War history, chronicling and commemorating almost every detail, Camp Casey isn’t one of the places that gets glorified or even remembered. Located somewhere in what’s now Arlington County, just miles from the White House and U.S. Capitol, Camp Casey was where regiments of African-American troops were trained to fight the Confederacy to end slavery.

While not the largest Union base for training U.S. Colored Troops (USCT), Camp Casey was one of the few located within the boundaries of a Confederate state. Yet, despite its historical significance, or perhaps because of it, Camp Casey has been largely lost to history.

In the decades after the war, as the white power structure reasserted itself across the South including in Virginia, the narrative of the Blue and the Grey took hold, two white armies battling heroically over conflicting interpretations of federal authority, brother against brother. Though slavery was surely an issue, African-Americans were pushed into the background, almost as bystanders.

In Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy, statues of Southern heroes were erected seemingly everywhere. One city street called Monument Avenue is lined with statues starting with one to Gen. Robert E. Lee (erected in 1890) and then (between 1900 and 1925) others to Gen. J.E.B. Stuart, Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, Navy Lt. Matthew Fontaine Maury and President Jefferson Davis.

If you drive north toward Washington along I-95, you see a gigantic Confederate battle flag flying next to the highway near Fredericksburg, the site of a Confederate victory in 1862, as well as frequent historical markers remembering not only battles but skirmishes. Across Virginia, there are eight national parks dedicated to Civil War battles and events.

The honors bestowed on Confederate leaders reach even into Arlington and Alexandria, though Union forces maintained control of those areas throughout the war. In 1920, at the height of Jim Crow segregation, parts of Route One, including stretches through or near black neighborhoods, were named in honor of Jefferson Davis, an avowed white supremacist who wanted to continue slavery forever. (In 1964, during the Civil Rights era, Davis’s name was added to an adjacent part of Route 110 near the Pentagon.)

Throughout Arlington itself, there are markers designating where Union forts and battlements were located. But there are no markers remembering Camp Casey, where the 23rd USCT regiment was trained and outfitted to go south to fight for African-American freedom, and where other USCT units bivouacked and drilled on their marches south. Even Camp Casey’s precise location has become something of a mystery with county historians offering conflicting accounts.

That haziness itself raises troubling questions, since Camp Casey arguably was the most historically significant Civil War site in Arlington. It was not just some static fort that never was attacked but an active training ground for hundreds of African-Americans to take up arms against the historic crime of black enslavement.

Camp Casey’s Role

Named after Major General Silas Casey, who oversaw the training of new recruits near Washington, Camp Casey was in operation from 1862-1865 and served as an important rendezvous point for Union troops, accommodating some 1,800 soldiers. It also housed prisoners of war and included a hospital.

General Casey wrote the Infantry Tactics for Colored Troops in 1863, differentiating the training procedures for colored troops based on the racist notion that black soldiers were not as well equipped for combat or to follow orders, and would need to be spurred in order to fight as valiantly as whites.

To give an idea of Camp Casey’s significance as a USCT base, a letter from the camp dated Aug. 2, 1864, directs Colonel Bowman of the 84th Pennsylvania volunteers to forward all recruits for the colored regiments in the Army of the Potomac to the recruiting rendezvous at Camp Casey instead of Camp Distribution as previously directed.

There were 138 African-American units serving in the Union Army during the Civil War, making up about one-tenth of the federal forces by the war’s end in April 1865, and at least 16 of those USCT regiments spent time at Camp Casey from 1864-1865, including the 6th, the 29th, and the 31st.

Camp Casey was the recruiting and training camp for the 23rd Regiment U.S. Colored Infantry with many recruits coming from Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania, Virginia, slave country about halfway between Washington and Richmond. In line with the standards of the time, USCT soldiers were not as well trained as white troops, were not given the best equipment, and were not paid as well.

USCT soldiers also faced hostility and mistrust from some white Northern troops, meaning that they often were not placed on the front lines but got assigned to “fatigue duty,” such as accompanying wagons and moving supplies. Nevertheless, USCT regiments battled heroically in several major clashes near the war’s end and faced special dangers not shared by their white Northern comrades.

When blacks were admitted into the Union Army, Confederate President Jefferson Davis instituted a policy that refused to treat them as soldiers but rather as slaves in a state of insurrection, so they could be murdered upon capture or sold into slavery. The USCT soldiers were trained to expect no mercy and no quarter if wounded or captured.

In accordance with that Confederate policy, U.S. Colored Troops did face summary executions when captured in battle. When a Union garrison at Fort Pillow, Tennessee, was overrun by Confederate forces on April 12, 1864, black soldiers were shot down as they surrendered. Similar atrocities occurred at the Battle of Poison Springs, Arkansas, on April 18, 1864, and the Battle of the Crater in Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864. In one of the most notorious massacres of black Union soldiers, scores were executed in Saltville, Virginia, on Oct. 2, 1864.

Bravery Under Fire

When the 23rd USCT was dispatched to join the battle against General Robert E. Lee’s vaunted Army of Northern Virginia, one of Union General George Meade’s staff officers wrote in a demeaning letter about them: “As I looked at them my soul was troubled and I would gladly have seen them marched back to Washington. We do not dare trust them in battle. Ah, you may make speeches at home, but here, where it is life or death, we dare not risk it.”

However, on May 15, 1864, the 23rd USCT engaged in what may have been the first clash between Lee’s army and black troops. A chronology of the 23rd’s history cites Noel Harrison at Mysteries & Conundrums describing how the 23rd came to the support of an Ohio cavalry unit confronting a Confederate force southeast of Chancellorsville.

According to an account uncovered by historian Gordon C. Rhea, one of the Ohio cavalrymen wrote, “It did us good to see the long line of glittering bayonets approach, although those who bore them were Blacks, and as they came nearer they were greeted by loud cheers.” The 23rd charged toward the Confederate position causing the Southern troops to withdraw, suffering several dead.

But the lack of faith in the African-American soldiers’ commitment and skill would play a decisive role in the disastrous Battle of the Crater. The 23rd and 29th USCT regiments, both of which spent time at Camp Casey, were part of Union General Ambrose Burnside’s Fourth Division, which was comprised of nine USCT regiments.

These regiments (the 23rd, the 29th, the 31st, the 43rd, the 30th, the 39th, the 28th, the 27th, and the 19th) were to lead the charge against Confederate defenses after a Union-crafted mine explosion blew an enormous crater under Confederate lines. Plans were changed, however, at the last minute when General Meade refused to allow the USCT to lead the advance.

Instead, the war-weary white troops commanded by General James Ledlie (a notorious drunk, whose lack of presence, much less leadership, during the battle was notable) led the way. Instead of charging around the crater, as the U.S. Colored Troops had been trained to do, the unprepared white replacements surged into the crater and were unable to get out. Union troops piled in on top of each other and were completely stuck, serving as easy targets for the Confederate soldiers above.

Finally, the USCT were called forth and served as a last stand against Confederate troops. Since they had initially been trained for the operation, they knew to avoid the crater and search for higher ground. But by that point, the botched attempt to take Petersburg had deteriorated into a massacre.

Lt. Robert K. Beecham, who had helped organize the USCT 23rd regiment, wrote about the soldiers’ bravery: “The black boys formed up promptly. There was no flinching on their part. They came to the shoulder like true soldiers, as ready to face the enemy and meet death on the field as the bravest and best soldiers that ever lived.”

According to the National Park Service, 209 USCT soldiers were killed in the battle with 697 wounded and 421 missing. The 23rd USCT from Camp Casey suffered the heaviest losses, with 74 killed, 115 wounded, and 121 missing. Confederate troops murdered a number of the USCT soldiers as they sought to surrender.

After the Battle of the Crater, soldiers from the 23rd were among the Union troops to enter the Confederate capital of Richmond after it fell and were present for General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

The Mystery of Camp Casey

Arlington historians have various takes on why the history of Camp Casey has been so neglected with even its precise location a mystery. The Arlington Historical Society’s stance is that it is not unusual to have lost a camp’s location, since Arlington and Alexandria were both heavily fortified during the Civil War and there were many camps located throughout the area.

Further, unlike a fort, which would consist of a large physical construction, most training camps had tents pitched in a field with only a few solid wood-framed buildings.

But Franco Brown, a historian with the Black Heritage Museum of Arlington, had a different take on why its location has been mostly lost to history. Calling Camp Casey “one of the biggest mysteries of the Civil War,” he has spent the past eight years researching Camp Casey and had encountered many of the same difficulties that I did in finding definitive information.

A lithograph of the Civil War’s Camp Casey in what is now Arlington County, though it was then known as Alexandria County.

While acknowledging that Camp Casey was not the biggest USCT base (Camp Penn in Pennsylvania and Camp Nelson in Kentucky were more important training locations), Brown said Camp Casey was largely lost to history because it wasn’t significant to the state’s dominant historians. They favored the conventional narrative of the Civil War, the storyline of two white armies, brothers fighting brothers.

“This information [about Camp Casey] does not want to be out, it is part of their power,” Brown said.

Brown said a key factor to consider when questioning how Camp Casey could have been ignored is to look at the attitudes of Virginians and the South after the war. At the war’s conclusion, resentments ran high, and it would have been particularly galling to Southerners loyal to the Confederacy to acknowledge that there were African-American soldiers actively training on Virginian soil to fight for the North.

“After the war you get things like the KKK, which was started by five Confederate generals,” Brown said, “and they don’t want mixing of the races. The South is still mad about the Civil War. The South is still mad at the black man, because he helped win the Civil War.”

This explanation takes into account the realities of Virginia’s society and culture following the war and, in many ways, continuing to today. While there may be some truth to the argument that the story of Camp Casey was simply lost in the chaos following the war, it isn’t hard to imagine a concerted effort by resentful whites to diminish the role of black soldiers during the war.

Where Was It?

There even remains the question: where was Camp Casey? When I set out to try to solve that mystery, I found remarkably little information and some of it was conflicting. The National Archives in Washington had little about the camp, mostly letters and muster rolls, and it wasn’t until I asked the Arlington Historical Society’s official historians that they seemed to give the matter much thought.

As far as the exact location of Camp Casey, there are a couple of conclusions. One thing seems certain, that it was located on or near Columbia Pike, then the main thoroughfare from Northern Virginia to Washington D.C.

Some letters from the time suggest that the camp was within sight of the Custis-Lee Mansion overlooking the Potomac River (now known as Arlington House above Arlington National Cemetery). That and other references to landmarks, including its supposed proximity to Freedman’s Village, led some historical investigators to place Camp Casey on the south side of Columbia Pike, not far from the Long Bridge which crossed into Washington.

An advertisement on Sept. 5, 1865, from the Daily National Republican, a Washington, D.C. newspaper in circulation from 1862-1866, announced the sale of government buildings at Camp Casey situated “about one and one-half miles from Long Bridge.”

Jim Murphy of the Historical Society explained, “We think it [Camp Casey] would have been between the Long Bridge and Fort Albany, in a field in what is currently the [south] parking lot of the Pentagon. […] We concluded it was located there after going through letters and dispatches from the camp that discuss the colored troops training next to a field.” (Long Bridge was located near today’s I-395’s 14th St. Bridge across the Potomac, and Fort Albany was just south of the current Air Force Memorial on Columbia Pike.) [To see a Civil War-era map of the area with some of the landmarks, click here.]

The Pentagon-parking-lot location would likely have put it within sight of the Custis-Lee mansion and would place it close to Freedman’s Village, a semi-permanent community for African-Americans freed by President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation who escaped the Confederacy and were settled on a portion of Lee’s plantation on the north side of Columbia Pike.

But Franco Brown cites other evidence in letters from the soldiers placing Camp Casey in the vicinity of Hunter’s Chapel, which no longer exists but was then located at the intersection of Glebe Road and Columbia Pike, about two miles further southwest from the location cited in the newspaper ad.

Brown also has a contemporaneous lithographic depiction that puts Camp Casey on a bluff near an area that looks to be around the intersection of what is now Glebe Road and Walter Reed Drive. “This area is at the highest apex of the surrounding land,” Brown said.

Brown also noted that the lithograph shows a tall tower in the distant left-hand background, the Fairfax Seminary, which still stands today as the Virginia Theological Seminary, about four miles further south in Alexandria.

Thus, he concluded that “the general vicinity [of Camp Casey] is likely between the present day locations of Glebe Road, Walter Reed Drive, Columbia Pike, and Route 50 [Arlington Boulevard].” Brown said he is confident in this conclusion saying, “I’ve got it within 500 yards of the original location.”

Brown’s location would place Camp Casey about three miles from the Long Bridge, among Fort Albany, Fort Berry and Fort Craig. There is also the possibility that Camp Casey involved several military way stations stretching along Columbia Pike, all known collectively as Camp Casey, which might explain the disparate descriptions of its location. [For an overview map of the forts in the Washington area, click here.]

Though Arlington County has no plans to honor Camp Casey (or even work to ascertain its exact location), county officials have responded to public pressure to acknowledge Freedman’s Village, where Sojourner Truth lived and worked for a time.

Freedman’s Village gave freed slaves refuge both during the Civil War and for decades later (until it was razed in 1900). In 2015, Arlington dedicated a new bridge on Washington Boulevard that crosses over Columbia Pike as “Freedman’s Village Bridge.”

It is a much deserved (albeit meager) recognition of the historic area which became a Freedom Trail for African-Americans, both those escaping slavery by heading northward and those marching southward as soldiers to end it.

Chelsea Gilmour, a lifelong resident of Arlington, Virginia, is an assistant editor at Consortiumnews.com.

The US Civil War was NOT fought over slavery, at least not over freedom for black people. It was fought over which economic system – industrial vs agararian – would prevail. Black people were merely a sideline to that conflict. And a sideline that has been used, quite effectively for propaganda purposes, for over 150 years. If all of the people on the plantations were white, or non of them were; or if all of the people were well paid or non of them were, the conflict would have been exactly the same. The ‘save the Union’ line hides one important fact i.e. Lincoln wished to save the Union, not for the sake of slavery, but for the sake of domestic capital. What won then is what is winning now – the 1%. Black people were used as pawns in the fight for economic control of the US. What should make that clear is the so-called “Tilden Hayes compromise” when the mask of concern for Black people was ripped off and the true face of the conflict was once again revealed.

Dear Sir.

I have just read yours of the 19th. addressed to myself through the New-York Tribune. If there be in it any statements, or assumptions of fact, which I may know to be erroneous, I do not, now and here, controvert them. If there be in it any inferences which I may believe to be falsely drawn, I do not now and here, argue against them. If there be perceptable in it an impatient and dictatorial tone, I waive it in deference to an old friend, whose heart I have always supposed to be right.

As to the policy I “seem to be pursuing” as you say, I have not meant to leave any one in doubt.

I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be “the Union as it was.” If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that. What I do about slavery, and the colored race, I do because I believe it helps to save the Union; and what I forbear, I forbear because I do not believe it would help to save the Union. I shall do less whenever I shall believe what I am doing hurts the cause, and I shall do more whenever I shall believe doing more will help the cause. I shall try to correct errors when shown to be errors; and I shall adopt new views so fast as they shall appear to be true views.

I have here stated my purpose according to my view of official duty; and I intend no modification of my oft-expressed personal wish that all men every where could be free.

Yours, A. Lincoln.