There have long been double standards when using the word “terrorism,” with acts by political or ideological allies spared the label while it is ladled over the actions of an adversary, a dilemma that has reappeared in the attack on a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado, writes ex-CIA analyst Paul R. Pillar.

By Paul R. Pillar

The lethal armed attack by a troublesome drifter against a Planned Parenthood clinic in Colorado Springs brings to mind two insufficiently recognized patterns about political violence and specifically terrorism, and how such violence tends to get treated in public debate and public policy.

One concerns the politicization and inconsistency with which such violence is or is not actively countered and not just verbally condemned, and often with which the T-word is applied at all. The inconsistency spans not only international differences that have been the basis for arguments over whether certain armed groups should be considered terrorists or freedom fighters, but also domestic political differences, including political differences in the United States.

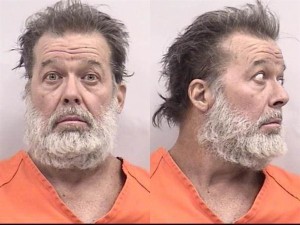

Mug shot of Planned Parenthood shooting suspect Robert L. Dear. (Photo from Colorado Springs Police Department.)

Although an investigation still in its early stages presumably will tell us more about the perpetrator in Colorado Springs, the incident clearly was an anti-abortion statement and more specifically a statement against Planned Parenthood, which anti-abortion activists recently have made their prime target.

According to a law enforcement official connected with the investigation, the gunman used the phrase “no more baby parts” to explain his attack, which was “definitely politically motivated.” The handling of the abortion issue and of violence associated with it has been for some time a prime illustration of the politicized and inconsistent treatment of terrorism.

The historian Philip Jenkins has documented how, during earlier waves of violence against clinics and health care professionals associated with abortion, the labeling of, and action against, this violence was heavily influenced by what political party or ideology was dominant. Jenkins notes that in the 1980s and early 1990s, the FBI did not even include such violence in its statistics on domestic terrorism, even though it fit the Bureau’s own definition of terrorism, and did not become involved in investigating it.

Jenkins writes, “Anti-abortion ‘terrorism’ only became such when a new political party took power in 1993.”

Now we are getting a replay of politically determined reactions to anti-abortion violence. President Barack Obama’s statement immediately after the shooting maintained agnosticism about motives and merely cited the incident as a reminder of the need for better gun control. Democratic presidential contenders issued statements supporting Planned Parenthood. Others pointed to the obvious connection between inflammatory rhetoric and the likelihood of an individual with violent inclinations acting on that rhetoric.

As for the Republican presidential candidates, in the words of the Washington Post‘s coverage over the weekend, a Republican field that “for much of the year has been full-throated in its denunciations of Planned Parenthood” was “nearly silent” in the first day after the shooting. Candidates emerged from their silence only when having to respond to questions on Sunday interview shows.

Carly Fiorina, whose own accusations against Planned Parenthood have included rhetoric about “butchering babies for body parts,” tried to deflect the issue by saying, “This is so typical of the left to immediately begin demonizing a messenger because they don’t agree with the message.”

The other pattern, applicable to both domestic and international terrorism, is the tendency to think of terrorism as a product of a specific group that combines in one package the ideology, the agenda, the organization, the know-how, and the operational initiative needed to yield terrorist attacks, when in fact these ingredients more often are in separate pieces.

Very often the initiative and execution of a terrorist attack come from a violence-inclined actor inspired and inflamed by someone else who provided an agenda and an ideology. The Colorado Springs incident, with the caveat that with further investigation we may still learn more, certainly appears to illustrate how this process repeatedly has worked with domestic terrorism.

In international terrorism, the pattern was displayed with Al Qaeda, often and incorrectly perceived as a kind of monolithic Terrorism International when in fact it became more of an ideology and radical brand name adopted and invoked by an assortment of actors who took the operational initiative to conduct attacks far and wide.

Something similar is now the case with ISIS, even though ISIS at the center has a far more substantial presence on the ground than Al Qaeda ever did. The attacks in Paris fall into this pattern. ISIS in the Middle East was a highly relevant inspiration, brand name, and cause with the capacity to inflame, but after more than two weeks of investigation, it still appears that the operational initiative and know-how, such as it was, for the attacks came from a radical gang based in Belgium.

Juan Cole, writing in The Nation, provides a useful guide for thinking about this aspect of ISIS. He describes the problem of an inhumane ISIS enclave in Syria and Iraq as a “quite separate challenge” from the problem of disaffected and radicalized youth in Muslim districts in Europe. Each of the two challenges needs its own set of policy responses, despite the connections between the two.

There are major and obvious differences between the corresponding challenges of each sort in domestic and international terrorism. What is most needed to reduce radicalism in a French banlieue is not what is most needed to reduce violence at abortion clinics in the United States. And what is most needed to control the destabilizing effects on the region of a so-called caliphate is not what is required to reduce inflammatory rhetoric in U.S. political campaigns.

In each case, however, we are dealing with separate but related entities that interact in a way that produces violent results. The separation between the trigger men and the idea men (and women) is not as great as apologists for the anti-Planned Parenthood rhetoric would like us to believe. Nor is the separation as little as implied by the belief that smashing with force someone’s mini-state in the Middle East will cure Islamist terrorism in the West.

Paul R. Pillar, in his 28 years at the Central Intelligence Agency, rose to be one of the agency’s top analysts. He is now a visiting professor at Georgetown University for security studies. (This article first appeared as a blog post at The National Interest’s Web site. Reprinted with author’s permission.)

Men and women who care about fetuses but not women or people who are the victims of US military adventures seem to abound in the USA.

btw, why was “Mr Dear” allowed to bring a big bag into a women’s health facility?

Governments are the greatest purveyors of terror by far. Fear remains the most effective means of social control.