After 14 years, trillions of dollars spent and hundreds of thousands of people dead with violence expanding, not abating perhaps it’s finally time to admit that the Bush-Obama “War on Terror” has been lost and that a new strategy addressing root causes is required, as Nat Parry describes.

By Nat Parry

Last week’s attacks in Paris offered a painful and tragic reminder that despite the unprecedented counterterrorism measures implemented since the attacks on New York and Washington 14 years ago, citizens in the West remain as vulnerable as ever to the threat of extremist violence. This may come as a bit of a shock to those who may have expected that the massive investment in fighting terrorism would have resulted in more safety and security by now.

With trillions of dollars spent on overseas military adventures, unprecedented “homeland security” and mass surveillance, and countless lives lost in U.S. wars, it’s not unreasonable to have thought that perhaps more measurable progress would have been made in countering the terrorist threat against the United States.

But with transportation agencies, football stadiums and tourist destinations across the U.S. now bolstering security following the attacks in Paris and with the Islamic State, or ISIS, promising more attacks to come in New York and Washington it is clear how vulnerable Americans remain to the threat of jihadist terrorism, despite all these sacrifices over the past decade and a half.

Efforts to contain terrorism certainly had precedents before President George W. Bush declared a wide-ranging and open-ended “War on Terror” in an address to Congress on Sept. 20, 2001, but the groundwork that was set in the weeks and months after 9/11 has come to define the overall approach to this Twenty-first Century challenge an approach that can now clearly be called an abject failure.

Despite some tactical differences between the Bush and Obama administrations in the way the war has been waged with a preference now on drone assassinations, for example, rather than full-scale invasions the “War on Terror” has essentially followed the same logic of pursuing something like total victory by eliminating every terrorist no matter where they are, with an unfortunately high tolerance for killing large numbers of innocent bystanders in the process.

Any honest appraisal of this effort would now conclude that the overall approach has borne out just as badly as the most pessimistic critics asserted back in 2001 and 2002, when the foundation was being laid for what Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld later dubbed the “Long War.”

Early Critics

With new organizations forming in the days after 9/11 with slogans such as “war is not the answer,” voices were being raised to assert that defeating terrorism required first of all that the United States stop engaging in it, based on the Hippocratic principle of “First do no harm.” The U.S. was also urged to devote at least as much attention to addressing the root causes of violent extremism as it was to addressing the military aspect of defeating jihadists on the battlefield. Among the principal causes identified included fighting global poverty and promoting human rights.

While the Bush administration announced in March 2002 that weapons and U.S. military advisers were being sent to countries such as Indonesia, Nepal, Jordan, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to mount proxy fights against terrorists, development advocates complained that no comparable effort was being made to alleviate the harsh economic conditions that provide the conditions in which extremism flourishes. Human rights organizations also warned that political repression carried out by some U.S. allies was doing more to fuel terrorism than to contain it.

In an open letter to Bush published on March 7, 2002, Human Rights Watch singled out Uzbekistan in particular as being an undeserving ally, urging the U.S. to reconsider its diplomatic and military support for the Central Asian dictatorship. The rights group warned, “In terms of human rights, Uzbekistan is barely distinguishable from its Soviet past, and [Uzbek] President [Islam] Karimov has shown himself to be an unreconstructed Soviet leader. You have to wonder whether this kind of record makes for a trusted ally or a foreign policy burden.”

Human Rights Watch also criticized expanding aid to Indonesia, where extra-judicial executions, torture and arbitrary detention were commonplace. It argued that increasing aid to Indonesia would “effectively reward the security forces for bad behavior.”

Yet, the Bush administration showed little interest in the correlation between human rights, political repression and militant extremism, a trend that has largely continued through today. In a visit to Central Asia earlier this month, for example, Secretary of State John Kerry met with autocratic rulers and officials from several countries considered some of the world’s worst rights offenders.

Although he had been urged by the human rights community to press the leaders on their records, Kerry largely downplayed human rights as he sought deeper U.S. ties with the region. As Reuters reported, “he took pains to avoid direct public criticism as he pursued security and economic concerns at the top of his agenda.”

Development Agenda

Back in 2002, when the “War on Terror” was being rolled out, calls for more engagement on development aid grew louder, with some of the strongest pleas coming directly from World Bank President James Wolfensohn.

In a speech at the Woodrow Wilson International Center, Wolfensohn argued that to combat terrorism, global poverty and other international problems must be addressed. “We will not create a safer world with bombs or brigades alone,” he said. Poverty “can provide a breeding ground for the ideas and actions of those who promote conflict and terror.”

Yet, when it comes to fighting global poverty, the U.S. has continued to display a seeming indifference to making this a priority, whether as part of a larger campaign against violent extremism or simply on humanitarian grounds.

Despite pressure placed on the U.S. following 9/11 to make development aid a central plank in the broader campaign against terrorism, the Bush administration resisted calls to increase funding for aid to the world’s poorest nations. Treasury Secretary Paul O’Neill insisted that foreign aid wasn’t proven to be effective, and so the U.S. blocked efforts by Great Britain and other countries to raise the level of aid going from international development organizations to poor nations.

After sustained criticism, the Bush administration reluctantly announced an increase in aid by $5 billion spread over several years. This would represent only a modest rise, however, in the U.S. contribution as measured by its percentage of GDP, which at that time was only 0.1 percent far short of the 0.7 percent that the United Nations had set for the minimal target of industrialized countries.

The UN has explained its 0.7 target as the minimum necessary towards promoting international security and stability, and has urged that meeting this target be considered a requisite for membership on the UN Security Council. For what it’s worth, however, current development aid by the United States stands at just 0.19 percent of its GDP, far behind the global leaders of Norway and Sweden, which donate 1.07 percent and 1.03 percent of their GDPs, respectively.

Climate Change Connection

Besides poverty and human rights, tackling climate change also emerged as an issue related closely to countering the long-term terrorist threat, but for years this connection was essentially ignored by high-level policymakers. While President Obama has just recently prioritized climate change, the Council on Foreign Relations for one was warning as far back as 2007 that climate change was contributing significantly to the terrorist threat.

The report noted for example that “declining food production, extreme weather events, and drought from climate change could further inflame tensions in Africa, weaken governance and economic growth, and contribute to massive migration and possibly state failure, leaving ‘ungoverned spaces’ where terrorists can organize.”

These concerns have since been reiterated by everyone from the Pentagon, which calls climate change a “threat multiplier” because it “has the potential to exacerbate many of the challenges we are dealing with today from infectious disease to terrorism,” to Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, who recently stated that “climate change is directly related to the growth of terrorism.”

Although Sanders was attacked for allegedly overstating a “direct” relationship between global warming and terrorism, there is indeed a mountain of evidence to support the assertion that there is at least a very strong correlation between these two trends.

In fact, it is well-documented that the current conflict in Syria, which has facilitated the rise of ISIS, was triggered by a series of socio-economic, political and environmental factors, including climate change. According to a recent report called “A New Climate for Peace,” an independent study commissioned by the foreign ministers of the G7 nations, a severe drought that hit Syria in 2006 was exacerbated by resource mismanagement and the impact of climate change on water and crop production.

“Herders in the northeast lost nearly 85 percent of their livestock, affecting 1.3 million people,” the report explained. “Nearly 75 percent of families that depend on agriculture suffered total crop failure.”

The widespread loss of livelihoods and food sources compelled farmers and rural families to migrate to overcrowded cities, stressing urban infrastructure and basic services, and increasing urban poverty. “More than 1 million people were food insecure, adding substantial pressure to pre-existing stressors, such as grievances and government mismanagement,” the G7 report pointed out. “This food insecurity was one of the factors that pushed the country over the threshold into violent conflict.”

U.S. Interventions

This violent conflict in turn was aggravated by previous and ongoing American meddling in the region. As the U.S. intelligence community had warned in 2006, a whole new generation of Islamic radicalism was spawned by the 2003 U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq. The consensus view of 16 U.S. spy services was that “the Iraq war has made the overall terrorism problem worse.” Part of this problem becoming worse was the rise of ISIS, which emerged in Iraq as a direct result of the U.S. occupation.

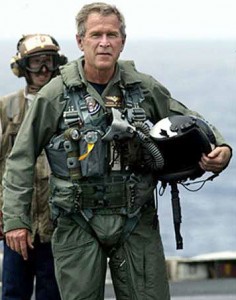

President George W. Bush in a flight suit after landing on the USS Abraham Lincoln to give his “Mission Accomplished” speech about the Iraq War on May 1, 2003.

The Washington Post reported in April 2015 that the core of ISIS is primarily made up of ex-Baathist military officials who were summarily disbanded from the Iraqi Army following the U.S. invasion. The organization grew largely thanks to the sectarian policies of U.S.-backed Prime Minister Nouri Maliki in stripping power from the Sunnis in favor of Shiite militias. The early growth of ISIS was further facilitated by the mass detentions of Iraqis in prisons such as Camp Bucca, which provided a fertile networking and recruiting opportunity.

As journalist Glenn Greenwald explained the process on Thursday’s episode of Democracy Now, “the reason there is such a thing as ISIS is because the U.S. invaded Iraq and caused massive instability, destroyed the entire society, destroyed all of the infrastructure, destroyed all order, and it was in that chaos that ISIS was able to emerge.”

After finally withdrawing from a devastated and traumatized Iraq in 2010, the U.S. then turned its attention to Libya, and decided to overthrow the government of Muammar Gaddafi through a massive bombing campaign. Following Gaddafi’s ouster, his caches of weapons ended up being shuttled to rebels in Syria, fueling the civil war there. The U.S. also began directly arming groups attempting to overthrow Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, with these weapons often ending up in the hands of jihadists such as the al-Nusra Front and ISIS.

Some of this was done in the full expectation that the policies would result in emboldening the extremists of groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda. According to a classified 2012 U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency memorandum, extremists were the driving forces in the Syrian civil war. As the memo stated, “the Salafists, the Muslim Brotherhood and [al-Qaeda in Iraq] are the major forces driving the insurgency in Syria.”

And yet, the U.S. was helping coordinate arms transfers to these same groups, leading directly to the rise of Islamic extremism there. These policies later morphed into efforts to promote “moderate rebels,” with no more success.

A $500 million Pentagon program meant to train and support moderate fighters was abandoned earlier this year after news emerged that the first group of U.S.-trained Syrian fighters was handily defeated by al-Nusra in late July. The Islamists apparently attacked the group and took an unspecified number hostage, with the remaining fighters fleeing and still unaccounted for.

Congressional hawks like Sen. John McCain, R-Arizona, withdrew their support for the program just a year after Congress authorized it. “It’s a bad, bad sick joke,” said McCain of the program, while Sen. Chris Murphy, D-Connecticut, called it “a bigger disaster than I could have ever imagined.”

‘Do You Realize What You’ve Done?’

These counter-productive strategies have not gone unnoticed by some world leaders, most of whom however are too polite to bring up the failures in public settings. One who does not play along by these unspoken diplomatic rules though is Russian President Vladimir Putin. In his address to the United Nations General Assembly in September, he directly challenged the architects of these policies, in what was surely seen in Washington as a major breach of etiquette.

“It would suffice to look at the situation in the Middle East and North Africa,” Putin said before the world. “Certainly political and social problems in this region have been piling up for a long time, and people there wish for changes naturally.”

He continued: “But how did it actually turn out? Rather than bringing about reforms, an aggressive foreign interference has resulted in a brazen destruction of national institutions and the lifestyle itself. Instead of the triumph of democracy and progress, we got violence, poverty and social disaster. Nobody cares a bit about human rights, including the right to life.”

He then issued a direct appeal to U.S. policymakers: “I cannot help asking those who have caused the situation, do you realize now what you’ve done? But I am afraid no one is going to answer that. Indeed, policies based on self-conceit and belief in one’s exceptionality and impunity have never been abandoned.”

As Putin suggested, there is little indication that much will change considering the recent past, with the central logic of the “War on Terror” having endured for 14 years now with no signs of it being revised in any substantial way.

In his address to Congress on Sept. 20, 2001, Bush declared that “Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated” a general policy that seems to remain in place today.

What we have seen transpire since Bush laid out his plan is precisely what many warned would happen: as one terrorist group is “defeated,” another one pops up to fill the void, a cycle that could conceivably go on forever, and by definition would doom the United States to a state of war and retribution for eternity. And although Obama has at times attempted to reassure Americans that the war was drawing to an end, his assurances often did more to confuse than to clarify.

Curious Memorial Day ‘Victory’ Speech

Last May, for example, Obama marked Memorial Day by noting that it was the first one since 9/11 that America was celebrating without being involved in a “major ground war.”

“For many of us, this Memorial Day is especially meaningful,” Obama said at Arlington National Cemetery on May 25. “It is the first since our war in Afghanistan came to an end. Today is the first Memorial Day in 14 years that the United States is not engaged in a major ground war.”

The statement made headlines as a milestone in the U.S.’s post-9/11 war footing a de facto declaration by the U.S. president that, perhaps, the war is over. But, as some media outlets pointed out, there was an element of disingenuousness to the announcement.

“American troops remain mired and at risk in [Iraq and Afghanistan], training and advising Iraqi forces against the Islamic State and Afghan forces fighting the Taliban,” noted the Washington Post.

Reuters pointed out that “U.S. forces are now involved in air campaigns against Islamic State militants in Iraq and Syria as well as training missions in Iraq and Afghanistan,” noting however that Obama has been “reluctant to relaunch ground operations in Iraq.”

Nevertheless, at the time Obama announced this milestone in winding down the “War on Terror,” 3,000 American military personnel were in Iraq working with the Iraqi army and U.S. airstrikes continued to pound ISIS targets. About 14,000 bombs had been dropped on Iraq and Syria since Sept. 2014, killing an estimated 12,500 fighters, according to Pentagon sources and hundreds of civilians, according to independent monitors.

President Barack Obama shakes hands with U.S. troops at Bagram Airfield in Bagram, Afghanistan, Sunday, May 25, 2014. (Official White House Photo by Pete Souza)

In Afghanistan, although the end of combat operations was formally announced last December, American forces “are playing a direct combat role” in secretive raids against al-Qaeda targets, The New York Times reported in February 2015.

In March 2015, it was announced that the United States will maintain nearly 10,000 service members in Afghanistan at least until 2016. This of course was revised again just last month, when Obama seemingly abandoned his longstanding goal of ending the war in Afghanistan, saying that he would leave 5,500 U.S. forces in the country beyond his departure from office in January 2017.

With all this in mind, Obama’s statement on Memorial Day earlier this year may have raised more questions than it answered. For one thing, what does “major” mean? Is saying that we are not in a “major ground war” an acknowledgement that the U.S. is no longer at war, or is it a tacit confirmation that we are in a minor ground war? If we are not at war, does that mean we are in a state of peace? If so, can pre-9/11 civil liberties, constitutional principles and privacy rights be restored, or are those gone for good?

Of course, all of these questions assume that terms like “war and peace” still have some commonly understood meanings, which is a dubious assumption 14 years into this ill-defined war. While some of us may retain memories of periods of relative peace, these are not memories that can be expected of all Americans.

Indeed, an entire generation of young people has now come of age in the era of the “War on Terror.” To put this into perspective: the 18-year-olds currently enlisting in the United States Armed Forces and being deployed to Afghanistan to fight the Taliban or being sent to Guantanamo to guard the prisoners who continue to languish there were just preschoolers when the Twin Towers came crashing down, and can scarcely remember a time at which their country was not “at war.”

While many Americans might still consider the not-so-new normal of war, militaristic displays at sporting events, routine scapegoating of Muslims, and the relinquishing of individual privacy and civil liberties to be somehow “weird,” to millions of young people, there is nothing weird about it.

While some of us may expect or quietly hope for a return to a time of peace, a time when we can expect both personal safety and individual liberty, it is sobering to realize that this expectation cannot possibly exist for those born and bred in this environment. After all, how can people expect to return to a normalcy that they have never known?

The sad fact is, normalcy to many Americans now means precisely this atmosphere of permanent war, militarism and hyper-security. But perhaps even sadder is that the tradeoff that we have been expected to make in terms of sacrificing blood and treasure in exchange for security and peace of mind now increasingly appears to be a false promise, a mirage on the horizon that always seems to disappear the further we travel across the desert of the “War on Terror.”

Nat Parry is the co-author of Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush. [This story originally appeared at Essential Opinion, https://essentialopinion.wordpress.com/2015/11/20/the-abject-failure-of-the-war-on-terror/

Truth is we are experiencing a war OF terror, a wholesale US terror war that in turn provokes acts of retail terrorism. But use of terror is as American as apple pie. Since 1798, the US has sent troops into other countries on more than 560 occasions to protect “US interests”. Since WWII, the US has bombed 30 countries, terrorizing from the air. Before we ever became a republic, Supreme Commanding General George Washington in 1779 issued the following orders to General Sullivan to be the largest campaign in the Revolutionary War of that year:

“The Expedition… is to be directed against the hostile tribes of the Six Nations of Indians… The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements….It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more….[T]he center of the Indian Country, should be occupied with all expedition… whence parties should be detached to lay waste all the settlements around, with instructions to do it in the most effectual manner, that the country may not be merely overrun, but destroyed. [Y[ou will not by any means listen to any overture of peace before the total ruinment of their settlements is effected. Our future security will be in their inability to injure us and in the terror with which the severity of the chastisement they receive will inspire them”.

-[Wikipedia, Sullivan Expedition; John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., Writings of George Washington,. XV (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1936) 189-93; Richard Drinnon, Facing West: The Metaphysics of Indian-Hating and Empire-Building. Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1980), 331].

Thank you for sharing that Washington quote. My thinking tends to line up with your own – that the WOT has not, in fact, been a failure, but a rousing success for those who designed it, and whose motives are actively hidden from us by all of their accomplices. The Washington quote supports that we (the US) have been using terror as a weapon for all of of our time here.

We must collectively discard the false narrative that the WOT has been a reaction to ‘religious extremism’ and all its evils, and realize that it is an act of evil itself, which we ourselves design, refine and use to control populations in lands where we wish to rape and pillage.

Sadly, it has always been the terrorists in our midst who declared the War on Terror.

They did so to disable democracy in any of its viable forms anywhere in the world.

The War on Terror is immensely profitable to those waging it: the real terrorists.

Look at the allies of those waging this War.

I wouldn’t want to meet them in a dark alley anytime.

A WAR ON…WHAT?

With all due respect to Nat Parry, there seems to be

something seriously out-of-focus in this analysis.

The term “war on terror” turned out to be an extremely

useable way to market fear of “the other”.

Concentrating for the minute only on American history,

there has almost always been a use for fear to

justify the massacres, murder and rape of Native Americans.

During American history blacks have been considered

a source of murder, violence, rape, destruction and

so forth (note lynching as only one example). “Aliens”

were once a guaranteed identifiable way to market

fear. (One Representative one quipped, “Add the

Ten Commandments as an amendment to an’ Alien

registration Law and it ill be defeated”.) “Commie’s”

were around every corner. “The Russians were

coming!” As a small child, I was taught to cower

under my wooden desk for protection from an

atomic bomb. Adults borrowed to the hilt to build

shelters.

On an international plane, one can go much

farther.

The ideas about “poverty” and “chaos” have much

validity indeed. The ideas are old and stem

from the days of World War Two when

they would force out the (American) “free

enterprise system” and be the end of civilization.

In previous eras there were tribal wars, wars of

colonialism, the Crusades, the wars which

form the basis of much of the Bible (Old and

New) and similar writings about religious

or godly (thus “justified” and “holy”) wars.

It seems that to speak of “jihadist terror”

fails to comprehend the essential nature

of jihad. Depending on whom you ask and

in what context.

Those who form our beliefs and who foster

warrior instincts will always find ways to

market their aims as “right to protect”, “security

reasons” and so forth.

If a large majority of any group is poor,

oppressed it creates reasons for controversy

and often chaos. It is not anything particular

to Muslims, or to blacks, or to “Gypsies”…

During many millenia, the human race has

failed to eliminate poverty and oppression.

To ask it to do so now is asking for

something which will not happen much as

we might wish, much as we all work for it

with passion and commitment.

Yes, the so-called”war on terror” was not won

and it never will be.

—–Peter Loeb, Boston, MA, USA

Excellent article summarizing the essential failures of militarist responses to social movements and longstanding grievances, the extreme and pathological hypocrisy and selfishness of US polticians.

The US has no concern for justice in foreign policy because the right wing needs foreign wars to pose as protectors, demand power, and accuse their opponents of disloyalty, just as Aristotle warned millennia ago of the tyrants over a democracy. US elections and mass media are controlled by economic powers, the rich and foreign powers, installing right wing traitors wrapped in the flag. Economic concentrations have been able to eliminate democracy as their primary enemy because the Constitution provides no protection of its institutions from money, which was little concentrated when it was written. Amendments are needed immediately, but will never be proposed because the institutions of democracy, elections and mass media, are already lost.

Kennedy sent VP LBJ to consult SE Asian leaders on the causes of the insurgency in Vietnam, and Johnson told him that the problem was not Communism (it was primarily a nationalist movement), it was poverty, ignorance, malnutrition, and disease. Kennedy was annoyed that this would not play with the right wing and kept on escalating the “minor war” until Pres LBJ finally allowed the military to set up a scam (the Gulf of Tonkin “Incident”) to involve us in another major war.

A War on Terror as effective as the misnamed US War on Poverty requires the US to devote massive resources to humanitarian aid.

The best way to ensure a rational foreign policy is to establish a College of Policy Analysis, a major national institution exploring every aspect of policy in every region, to determine what will really work for everyone in the long term, rigorously protecting the minority opinion or “enemy” viewpoint from groupthink. so as to lead public debate to a far higher standard. Citizens should be able to sue the Executive and Legislative branches in courts of the College for violations of what had been determined to serve the interests of humanity. This was recently proposed to the Department of Education, on a small scale to prepare for federal funding, and their response was that they don’t have the “authority” to educate. Force is the only alternative for true patriots.

It is sad that the corruption has gone so far, but worse to pretend otherwise. We and the victims of US aggression will not be liberated by education or political action. History is waiting for a generation of suicide bombers to take out the rich, the right wing, their mass media, and the centers of our three branches of corrupt government. Who would miss any of them if democracy was restored? The Saudis and AlQaeda may have been right.

Reality check on Daesh:

http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article43490.htm

Remembering the country’s temperament after 9/11/2001, I can recall it was all ahead full, when it came to our country’s thirst for the satisfaction of revenge. Little, was known of the 1996 Project for a New American Century ideology. No one paid any attention, to an Israeli author Oded Yinon, and his plan for Israeli dominance of the Middle East. Westley Clark, had yet let the cat out of the bag, with his outing of the invasion plan for seven nations within five years. Americans, were convinced that 9/11/01 was an Islamic Terrorist attack. When it came to Climate Change, Americans were to concerned about the price of gasoline, for their low mileage SUV’s. Well, at least that’s how the Main Stream Media people put it. Americans, have been, and still are, being flat out lied too. What, I am starting to notice though, is how more people with each attack, are beginning to wonder, if this all maybe manufactured. Seriously, some even point to the TV show ‘the Blacklist’, as maybe being a model for the intrigue, that surrounds our everyday modern world. My point being, is articles such as Nat Parry’s need to be read by a wide audience. Educating the masses is possibly the best thing that can be done. I’ll admit that by reading comments, and often following these commenters provided links, I have, and still are, learning a lot I would have never learned by just following the stooges amongst our MSM. So, I will close by thanking not only this author, but all of you commenters, as well.

Right you are. No one paid attention. Still are not for the most part.

That’s America for you. And when the shit finally hits the fan, the response

will be “what happened?”

If you want to win something, you have to start out by defining in a way that’s logically tenable. A “War on Terror” has a built-in oxymoron, since war is something which creates terror. How do you win something which can’t logically be won? The closest you can come is to build more and more powerful tools to delude yourself, and ignore what other people think.

The problem here is that the author is using the wrong metrics to measure the success of the GWOT. If you look at it’s de-facto reason — as a US domestic strategy to cow the already submissive Democrats and advance the US political agenda even further to the right — it’s been a rousing success! After all, how has it hurt the political conservatives in this country who launched it? They’re still doing fine, thank you very much, holding high offices or positions. Sure they occasionally get criticized as having caused 100s of thousands of deaths of Iraqis and other Arabs, and ~6000 US soldiers, but they just feign outrage that the critics are siding with terrorists and want to give-in to Al Qaeda/ISIS/etc, etc, a ploy which works 95% of the time, and they come out just as strong or stronger.

Eddie, do you mean like the 2004 presidential candidate John F. Kerry, “I voted for it, before I voted against it,” Democrates? Hillary went so hawk, she did everything but fly a B52. Who, will ever forget, or forgive, Nancy ‘impeachments off the table’ Pelosi, for the shame she brought to this nation’s constitutional correctness? I’m not the first to bring this up, but imagine a ‘retreating out of Beirut’ Ronald Reagan today, amongst his dearly beloved Republicans. BTW, I agreed with Reagan on pulling out of Beirut. I asked the same question back then, ‘why are we even there’. Eddie, you are on to something, and yes America somehow must head towards the center, and maybe a little more to the left, if we are to really want and bring peace about. Until we as a society come to seek out, and prosecute, the people who fund these terrorist, we will continue to be attacked. This is a cycle, that must be broken, before anything good can ever come of all of this.

Thank you for focusing on the “War on Terror”. The very term “War on Terror” is a camouflage by the Israelis.

Glenn Greenwald discussed Rémi Brulin’s research into this term on Democracy Now, which revealed “the term ‘terrorism’ really entered and became prevalent in the discourse of international affairs in the late ’60s and the early ’70s, when the Israelis sought to use the term to universalize their disputes with their neighbors, so they could say, “We’re not fighting the Palestinians and we’re not bombing Lebanon over just some land disputes. We’re fighting this concept that is of great – a grave menace to the world, called ‘terrorism.'”

http://www.democracynow.org/2015/1/13/glenn_greenwald_on_how_to_be

The recent Paris attacks prompted Senator Schumer, Israel’s self-styled “guardian” of Israel, to equate this war with Israel’s war.

http://mondoweiss.net/2015/11/against-terrorism-schumer

The Israelis want to distract from the massive wave of innocent refugees brutally driven from their homes by the Zionist army during the establishment of Israel, a brutal treatment of innocent Palestinians that has continued unabated to this day. As one small example,

http://mondoweiss.net/2015/11/justice-tariq-khdeir

Even the legendary U.N. vote to partition Palestine was obtained by the Zionists using financial muscle, both bribes and threats, and even death threats to U.N. members, a true mafia-style “offer they couldn’t refuse”.

Key historical facts that are omitted in the American and European press are traced out in “War Profiteers and the Roots of the War on Terror” (recommended by Ray McGovern) at

http://warprofiteerstory.blogspot.com

Thank you for reporting on the events behind the scenes and advancing the discussion.

GWOT is dead. Long live GWOT.

F. William Engdahl discusses the historical background to what is taking place now in Syria, and how it plays into the current geopolitical agenda of the US/NATO military powers.

https://www.corbettreport.com/interview-1012-william-engdahl-explains-the-context-of-the-paris-attacks/