Special Report: Black History Month celebrates talented African-Americans, but it also should be a time to reflect on distorted white history that has ignored damage inflicted by racist ideologues, like how Thomas Jefferson’s hypocrisies helped give us the Civil War and the Tea Party, writes Robert Parry.

By Robert Parry

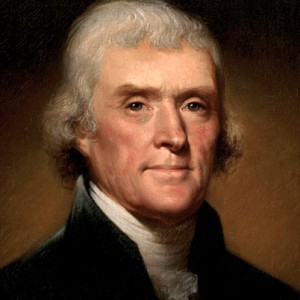

Thomas Jefferson, the lead author of the Declaration of Independence, may be the Founder who most influences and bedevils modern times, a hero to progressives for penning rhetoric to express the young nation’s noblest ideals and an icon of the Tea Party for redefining the U.S. Constitution to incorporate the Southern slaveholders’ hostility to a strong federal government.

Beyond his ideological influence on modern America, Jefferson comes across as the most contemporary Founder: skeptical of organized religion, committed to revolutionary politics, fascinated by how art can enhance public places, interested in the scientific method, advocating the value of higher education, and torn by the complexities of life.

As Jon Meacham wrote in his largely flattering Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, “Jefferson is the founding president who charms us most. With his grace and hospitality, his sense of taste and love of beautiful things of silver and art and architecture and gardening and food and wine Jefferson is more alive, more convivial.”

But there is another way to see Jefferson: as an epic phony whose true modernity was most apparent in his talent for manipulating language. He was a master of propaganda, a before-his-time genius at “branding.” He was a wordsmith who could wrap even his most depraved actions in pleasing or confusing words.

If Americans were ever to take off their rose-colored glasses through which they have viewed Jefferson for generations, they would see a man who believed few of the words he wrote, particularly in regard to freedom and slavery but also on a range of other topics, such as his lectures against personal debt and for a modest republican lifestyle.

Though the young Jefferson did make modest stabs at reforming the South’s barbaric slave system and he would occasionally revert back to calling it a “hideous blot” on the new nation Jefferson built his post-Revolution political career as a protector of Virginia’s plantation structure, albeit behind the shield of innocuous or opaque words like “states’ rights,” “Missourism” and anti-“consolidationism.”

Beyond politics, Jefferson’s hypocrisy served his own personal interests. His consistent actions on behalf of slavery helped his own net worth, as he battled creditors who had helped him finance his penchant for luxury goods. At Monticello, he carefully calculated the monetary value of his scores of slaves, had the lash applied to boy slaves as young as 10, and apparently sexually exploited at least one and possibly other slave girls.

But perhaps the most devastating indictment of Jefferson’s hypocrisy is that his action and inaction set the United States on course for the Civil War by creating the ideological rationalization for secession.

Further, his invention of “states’ rights” by willfully misinterpreting the Constitution’s clear language laid the groundwork for the persecution of African-Americans through slavery, Jim Crow and, indeed, to the present day as America’s rightists continue to cite “states’ rights” to curtail voting rights and pass other laws that disproportionately target blacks.

It was Jefferson, not South Carolina’s Sen. John Calhoun, who devised the states’-rights concepts of “nullificationism” and even secession. It was also Jefferson, not President Andrew Jackson, who established the policies toward Native Americans that led to their expulsion to west of the Mississippi, the Trail of Tears and decades of genocide.

Loving Jefferson

Yet, Jefferson is best known for writing in the early days of America’s War of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Yet, at the time of those words, Jefferson was a major Virginia slaveholder who considered African-Americans to be anything but equal to whites. As he explained in his Notes on the State of Virginia and other commentaries, he considered blacks profoundly inferior to whites, a conclusion that he supported with subjective analysis and pseudo-science.

Jefferson judged African-Americans inferior because their skin color and other features were less pleasing to the eye and because they allegedly didn’t write poetry (which would have been a difficult and risky task for them since slaves were kept illiterate and could be severely punished for learning to read and write).

Jefferson further argued that blacks could not be allowed to remain in the United States if freed because black males would be a threat to rape white women. Fancying himself an early anthropologist, Jefferson placed blacks somewhere between orangutans and whites, and he believed that male orangutans raped black women in Africa in an attempt to rise up the evolutionary scale.

In Jefferson’s view, black males would be driven by the same base instinct to rape white women if blacks were emancipated and permitted to live among whites. He argued that black people would seek sex with white people “as uniformly as is the preference of the Oranootan for the black women over those of his own species.”

Jefferson apparently failed to recognize the cruel irony in his pseudo-science, given that while it was rare for black men to rape white women in the slave South, the prevalence of white men sexually imposing themselves on black women including at Monticello was common.

But Jefferson’s hypocrisy did not stop at race. Today’s Tea Partiers are fond of recalling his famous letter in 1787 from Paris, declaring that “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is it’s [sic] natural manure.”

The context of the letter was Jefferson downplaying the threat posed by Shays’ Rebellion, which had contributed to George Washington and the Federalists meeting in Philadelphia to throw out the Articles of Confederation and the concept of state sovereignty in favor of the U.S. Constitution with its powerful federal government enacting the “supreme” laws of the land. Jefferson felt the Constitution was an overreaction to Shays’ Rebellion.

Yet, Jefferson’s bravado about “the blood of patriots and tyrants” was more a rhetorical flourish than a principle that he was ready to live by. In 1781, when he had a chance to put his own blood where his mouth was when a Loyalist force led by the infamous traitor Benedict Arnold advanced on Richmond, Virginia, then-Gov. Jefferson fled for his life on the fastest horse he could find.

Jefferson hopped on the horse and fled again when a British cavalry force under Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton approached Charlottesville and Monticello. Gov. Jefferson abandoned his neighbors in Charlottesville and left his slaves behind at Monticello to deal with the notoriously brutal Tarleton.

In other words, Jefferson may have been America’s original “chicken hawk,” talking cavalierly about other people’s blood as “manure” for liberty but finding his own too precious to risk. Nevertheless, Jefferson later built his political career by questioning the revolutionary commitment of Alexander Hamilton and even George Washington, who repeatedly did risk their lives in fighting for American liberty.

Modest Republican Virtue

Another area of hypocrisy was Jefferson’s denunciation of debt, luxuries and spendthrift ways during his years representing the new country in France.

As historian John Chester Miller wrote in his 1977 book, The Wolf by the Ears, “To Jefferson, the abandon with which Americans rushed into debt and squandered borrowed money upon British ‘gew-gaws’ and ‘trumpery’ vitiated the blessings of peace.

“From Paris an unlikely podium from which to sermonize Jefferson preached frugality, temperance, and the simple life of the American farmer. Buy nothing whatever on credit, he exhorted his countrymen, and buy only what was essential. ‘The maxim of buying nothing without money in our pocket to pay for it,’ he averred, ‘would make of our country (Virginia) one of the happiest upon earth.’

“As Jefferson saw it, the most pernicious aspect of the postwar preoccupation with pleasure, luxury, and the ostentatious display of wealth was the irremediable damage it did to ‘republican virtue.’”

But Jefferson himself amassed huge debts and lived the life of a bon vivant, spending way beyond his means. In Paris, he bought fancy clothes, collected fine wines, and acquired expensive books, furniture and artwork. It was, however, his slaves back at Monticello who paid the price for his excesses.

“Living in a style befitting a French nobleman, his small salary often in arrears, and burdened by debts to British merchants which he saw no way of paying, Jefferson was driven to financial shifts, some of which were made at the expense of his slaves. In 1787, for example, he decided to hire out some of his slaves a practice he had hitherto avoided because of the hardship it wreaked upon the slaves themselves,” Miller wrote.

Upon returning to the United States, Jefferson reinvented himself as a more modestly attired republican, but his tastes for the grandiose did not abate. He ordered elaborate renovations to Monticello, which deepened his debt and compelled his slaves to undertake strenuous labor to implement Jefferson’s ambitious architectural designs.

Needing to squeeze more value from his slaves, Jefferson was an aggressive master, not the gentle patrician that his apologists have long depicted.

According to historian Henry Wiencek in his 2012 book, Master of the Mountain: Thomas Jefferson and His Slaves, Jefferson “directed his manager, Nicholas Lewis, to extract ‘extraordinary exertions’ of labor from the slaves to stay current with his debt payments. Some slaves had endured years of harsh treatment at the hands of strangers, for to raise cash, Jefferson had also instructed Lewis to hire out slaves. He demanded extraordinary exertions from the elderly: ‘The negroes too old to be hired, could they not make a good profit by cultivating cotton?’”

Jefferson was callous as well toward his young slaves. Reviewing long-neglected records at Monticello, Wiencek noted that one plantation report to Jefferson recounted that the nail factory was doing well because “the small ones” ages 10, 11 and 12 were being whipped by overseer, Gabriel Lilly, “for truancy.”

Sexual Predator?

Another of Jefferson’s supposedly high-minded principles was his rejection of miscegenation, sexual relations between blacks and whites. For generations, Jefferson’s defenders have insisted that he lived nearly a chaste life after his wife died in 1782 and that he abhorred the notion of blacks and whites copulating.

But modern scholarship is now in near consensus that Jefferson seduced Sally Hemings, a teen-age slave girl who was a companion to one of his daughters during Jefferson’s years in Paris, and that he kept Hemings as his concubine for the rest of his life. After many decades in denial, even some Jefferson acolytes, like Meacham, accept this troubling relationship as historical reality.

The old version of the story was to portray Hemings as a promiscuous slave vixen and insist that the Great Man would never have brought a mulatto girl like Hemings into his bed. Despite the curious coincidence that Hemings tended to give birth nine months after one of Jefferson’s visits to Monticello and the discovery of male Jefferson DNA in Hemings’s descendants the argument went that Hemings must have been sleeping around with Jefferson’s nephews.

When confronted with the fact that one of Hemings’s sons, Madison Hemings, said his mother late in life recounted to him how Jefferson had imposed himself on her in Paris and continued to have sex with her during her years at Monticello, Jefferson’s defenders suggested that Sally Hemings was not only a slut but a liar who was trying to enhance her standing and that of her offspring by claiming Jefferson as the father.

Now, however, with most scholars agreeing that Jefferson did have a sexual relationship with Hemings who was a daughter of his slave-owning father-in-law and thus his wife’s half-sister the new defense of Jefferson was that the relationship was a true love affair, with Hemings portrayed as a kind of modern-day independent woman making choices about her lovers.

But the reality was that Hemings was only 14 when she moved into Jefferson’s residence in Paris in 1787 and was thus more likely the victim of a sexual predator. He was in his mid-40s.

According to Madison Hemings’s account, his mother “became Mr. Jefferson’s concubine [in Paris]. And when he was called back home she was enciente [pregnant] by him.” Jefferson was insistent that Sally Hemings return with him, but her awareness of the absence of slavery in France gave her the leverage to insist on a transactional trade-off; she would continue to provide sex to Jefferson in exchange for his promise of good treatment and the freedom of her children when they turned 21, Madison Hemings said.

Jefferson’s Doubles

Some scholars, including Wiencek, also now give credence to the contemporaneous accounts of Jefferson having sex with one or more other female slaves and thus having a direct role in populating Monticello with his own dark-skinned lookalikes.

“In ways that no one completely understands, Monticello became populated by a number of mixed-race people who looked astonishingly like Thomas Jefferson,” wrote Wiencek. “We know this not from what Jefferson’s detractors have claimed but from what his grandson Jeff Randolph openly admitted. According to him, not only Sally Hemings but another Hemings woman as well ‘had children which resembled Mr. Jefferson so closely that it was plain that they had his blood in their veins.’

“Resemblance meant kinship; there was no other explanation. Since Mr. Jefferson’s blood was Jeff’s blood, Jeff knew that he was somehow kin to these people of a parallel world. Jeff said the resemblance of one Hemings to Thomas Jefferson was ‘so close, that at some distance or in the dusk the slave, dressed in the same way, might be mistaken for Mr. Jefferson.’ This is so specific, so vivid ‘at some distance or in the dusk’ that Jeff had to be relating a likeness he had seen many times and could not shake the memory.”

During a dinner at Monticello, Jeff Randolph recounted a scene in which a Thomas Jefferson lookalike was a servant tending to the table where Thomas Jefferson was seated. Randolph recalled the reaction of one guest: “In one instance, a gentleman dining with Mr. Jefferson, looked so startled as he raised his eyes from the latter to the servant behind him, that his discovery of the resemblance was perfectly obvious to all.”

In the 1850s, Jeff Randolph told a visiting author that his grandfather did not hide the slaves who bore these close resemblances, since Sally Hemings “was a house servant and her children were brought up house servants so that the likeness between master and slave was blazoned to all the multitudes who visited this political Mecca” and indeed a number of visitors did make note of this reality.

Even Jefferson admirer Meacham acknowledged this fact, including in Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power, a quote by Elijah Fletcher, a visitor from Vermont: “The story of Black Sal is no farce That he cohabits with her and has a number of children by her is a sacred truth and the worst of it is, he keeps the same children slaves an unnatural crime which is very common in these parts This conduct may receive a little palliation when we consider that such proceedings are so common that they cease here to be disgraceful.”

Meacham observed that Jefferson “was apparently able to consign his children with Sally Hemings to a separate sphere of life in his mind even as they grew up in his midst.

“It was, to say the least, an odd way to live, but Jefferson was a creature of his culture. ‘The enjoyment of a negro or mulatto woman is spoken of as quite a common thing: no reluctance, delicacy or shame is made about the matter,’ Josiah Quincy Jr. of Massachusetts wrote after a visit to the Carolinas. This was daily reality at Monticello.”

This “daily reality” was also a troubling concern among Jefferson’s white family though the Great Man would never comment.

“Frigid indifference forms a useful shield for a public character against his political enemies, but Jefferson deployed it against his own daughter Martha, who was deeply upset by the sexual allegations against her father and wanted a straight answer Yes or no? an answer he would not deign to give,” wrote Wiencek.

Before his death, Jefferson did free several of Sally Hemings’s children or let them run away presumably fulfilling his commitment made in Paris before Hemings agreed to return to Monticello. “Jefferson went to his grave without giving his family any denial of the Hemings charges,” Wiencek wrote.

Though it is an uncomfortable point to make and may be impossible to prove the historical record increasingly makes Jefferson out to be something of a rapist, exploiting at least one and possibly more girls who were trapped on his property, who indeed were his property, and thus had little choice but to tolerate his sexual advances.

Monetizing People

But Jefferson’s apparent sexual predations are only part of the story. His plantation records show clearly that he viewed fertile female slaves as exceptionally valuable because their offspring would increase his assets and thus enable him to incur more debt. He ordered his plantation manager to take special care of these “breeding” women.

“A child raised every 2. years is of more profit than the crop of the best laboring man,” Jefferson wrote. “[I]n this, as in all other cases, providence has made our duties and our interests coincide perfectly.”

According to Wiencek, “The enslaved people were yielding him a bonanza, a perpetual human dividend at compound interest. Jefferson wrote, ‘I allow nothing for losses by death, but, on the contrary, shall presently take credit four per cent. per annum, for their increase over and above keeping up their own numbers.’ His plantation was producing inexhaustible human assets. The percentage was predictable.”

To justify his perpetuation of slavery a repudiation of his declared anti-slavery views as a young man Jefferson claimed that he was merely acting in accordance with “Providence,” which in Jefferson’s peculiar view of religion always happened to endorse whatever action Jefferson wanted to take.

Yet, while Jefferson’s rationalizations for slavery were repugnant, his twisting of the Founding Narrative may have been more significant and long-lasting, carrying to the present day with the Tea Party’s claims that states are “sovereign” and that actions by the federal government to promote the general welfare are “unconstitutional.”

The reason the Tea Partiers get away with presenting themselves as “constitutionalists” is that Thomas Jefferson engineered a revisionist interpretation of the actual document, which as written by the Federalists and ratified by the states created a federal government that could do almost anything that Congress and the President agreed was necessary for the country.

That was the view of both the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists who mounted a fierce though unsuccessful campaign to defeat the Constitution. [For details, see Consortiumnews.com’s “The Right’s Made-up ‘Constitution.’”]

Southern Anti-Federalists, such as Patrick Henry and George Mason, argued that the Constitution, though it implicitly accepted slavery, would eventually be used by the North to free the slaves. Or, as Patrick Henry colorfully told Virginia’s ratifying convention in 1788, “they’ll free your niggers!”

Though the Constitution eked through to passage, the fear of Southern plantation owners that they would lose their huge investment in human chattel did not disappear. Indeed, the fear intensified as it became clear that many leading Federalists, including the new government’s chief architect Alexander Hamilton, were abolitionists.

As a young politician, Jefferson had cautiously and unsuccessfully backed some reforms to ameliorate the evils of slavery. However, after the Revolution, he made clear to supporters that he understood that any anti-slavery positions would destroy his political viability among his fellow plantation owners in the South.

While in Paris as the U.S. representative, Jefferson rebuffed offers to join the abolitionist Amis des Noirs because by associating with abolitionists he would impair his ability to do “good” in Virginia, historian John Chester Miller noted, adding: “Jefferson’s political instinct proved sound: as a member of the Amis des Noirs he would have been a marked man in the Old Dominion.”

Jefferson vs. Hamilton

In the 1790s, as Hamilton and the Federalists worked to create the new government that the Constitution had authorized, a counter-movement emerged, to reassert states’ rights as defined by the Articles of Confederation, which the Constitution had obliterated.

This backlash, which sought to protect the business of slavery, took shape behind the charismatic figure of Jefferson, who skillfully reframed the issue, not as defense of slavery but as resistance to a strong central government and the reassertion of the primacy of the states.

Though Jefferson had played no role in drafting the Constitution or the Bill of Rights he was in Paris at the time he simply interpreted the Constitution as he wished, similar to his frequent invocation of Providence as, amazingly, always favoring whatever he wanted.

There was an Orwellian brilliance to Jefferson’s strategy even though it predated Orwell by more than a century. Just ignore the Constitution’s clear language, such as when it mandates in Article I, Section 8 that Congress “provide for the general Welfare of the United States” and grants Congress the power “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the foregoing Powers, and all other Powers vested by this Constitution in the Government of the United States.”

Jefferson simply staked out a position in favor of “strict construction,” i.e. that only the specific powers mentioned in Article I, Section 8, not the sweeping language of those other two clauses were constitutionally invested in Congress. That didn’t make any real sense, of course. Beyond the specific list of powers in Article I, Section 8, such as coining money, regulating commerce, etc., the federal government would have to undertake many unforeseen actions, which was why the Framers had included the broad language that they did.

But Jefferson built a political movement based on the absurd notion that the Framers hadn’t meant what the Framers had clearly written. Jefferson went even further and reasserted the concept of state sovereignty and independence that George Washington, James Madison and other Framers had despised and intentionally expunged when they threw out the Articles of Confederation, which indeed had bestowed sovereignty and independence on the states. The Constitution shifted national sovereignty to “We the People of the United States.”

And, despite the Constitution’s explicit reference to making federal law “the supreme law of the land,” Jefferson exploited the lingering resentments over ratification to reassert the states’ supremacy over the federal government. Often working behind the scenes even while serving as Vice President under President John Adams Jefferson promoted each state’s right to nullify federal law and even to secede from the Union.

Aiding Jefferson’s cause was the recognition by James Madison that his political future in slave-owning Virginia, too, was dependent on him forsaking his earlier Federalist allies and shifting his allegiance to his neighbor and fellow slaveholder, Jefferson. Madison’s break with his old allies, George Washington and Alexander Hamilton, gave Jefferson’s revisionist take on the Constitution a patina of legitimacy given Madison’s key role as one of the Framers.

Jefferson spelled out this political reality in a 1795 letter to Madison in which Jefferson cited what he called “the Southern interest,” because, as author Meacham observed, “the South was his personal home and his political base.” It was the same for Madison. [For more on Madison’s role, see Consortiumnews.com’s “The Right’s Dubious Claim to Madison.”]

Winning the Presidency

In his rise to power, Jefferson waged a nasty propaganda war against the Federalists as they struggled to form a new government and avoid getting drawn into a renewed conflict between Great Britain and France. Jefferson secretly funded newspaper editors who spread damaging personal rumors about key Federalists, particularly Hamilton who as Treasury Secretary was spearheading the new government’s formation.

Though Jefferson framed his argument as opposing a powerful central government, his political actions dovetailed with the interests of slaveholders and his own personal finances. For instance, Jefferson protested the Federalists’ disinterest in pursuing compensation from Great Britain for slaves freed during the Revolutionary War, a high priority for Jefferson and his plantation-owning allies. Jefferson correctly perceived that Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, two staunch opponents of slavery, had chosen not to make compensation a high priority.

Also Jefferson’s interest in siding with France against Great Britain was partly colored by his large financial debts owed to London lenders, debts that might be voided or postponed if the United States went to war against Great Britain.

Then, with French agents aggressively intervening in U.S. politics to push President John Adams into that war against Great Britain, the Federalist-controlled Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts, which Jefferson’s political movement deftly exploited to rally opposition to the overreaching Federalists.

By the election of 1800, Jefferson had merged his political base in the slave-economy South (aided by the Constitution’s clause allowing slave states to count slaves as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of representation) with an anti-Federalist faction in New York to defeat Adams for reelection. The three-fifths clause proved crucial to Jefferson’s victory.

As President, Jefferson took more actions that advanced the cause of his slaveholding constituency, largely by solidifying his “states’ rights” interpretation of the Constitution. But Jefferson and his revisionist views faced a formidable opponent in Supreme Court Chief Justice John Marshall, a fellow Virginian though one who considered slavery the likely ruin of the South.

As historian Miller wrote: “While Jefferson could account for Hamilton a West Indian ‘adventurer’ goaded by ambition, unscrupulous in attaining his ends, and wholly devoid of state loyalties he could not understand how John Marshall, a Virginian who, under happier circumstances, Jefferson might have called ‘cousin John,’ could cast off all feeling for his ‘country’ (i.e. Virginia) and go over to the ‘enemy’ the monstrous regiment of bankers, speculators, businessmen, and other vultures bent upon sucking the very lifeblood from the Old Dominion.

“As Marshall saw it, Jefferson was trying to turn the clock back to the Articles of Confederation a regression that would totally paralyze the federal government. ‘The government of the whole will be prostrated at the feet of the members,’ Marshall predicted, ‘and the grand effort of wisdom, virtue, and patriotism, which produced it, will be totally defeated.’

“The question of slavery never bulked larger on Jefferson’s horizon than when John Marshall, from the eminence of the Supreme Court, struck down acts of the state legislatures and aggrandized the powers of the federal government. For slavery could not be divorced from the conflict between the states and the general government: as the Supreme Court went, so might slavery itself go.

“States’ rights were the first line of defense of slavery against antislavery sentiment in Congress, and Jefferson had no intention of standing by idly while this vital perimeter was breached by a troop of black-robed jurists.”

Selling Out Haiti

Jefferson also reversed the Federalists’ support for the slave rebellion in St. Domingue (now Haiti), which had overthrown a ruthlessly efficient French plantation system that had literally worked the slaves to death. The violence of that revolution on both sides shocked Jefferson and many of his fellow slaveholders who feared that the rebellion might inspire American blacks to rise up next.

Alexander Hamilton, who had been raised in the West Indies and came to despise slavery from his first-hand experience there, assisted the black slave leader, the self-taught and relatively moderate Toussaint L’Ouverture, in drafting a constitution, and the Adams administration sold weapons to the former slaves.

After taking office, however, President Jefferson reversed those policies. He conspired secretly with the new French dictator Napoleon Bonaparte on a French plan to retake St. Domingue with an expeditionary force that would re-enslave the blacks. Jefferson only learned later that Napoleon had a second phase of the plan, to move to New Orleans and build a new French colonial empire in the heart of North America.

Napoleon’s army succeeded in capturing L’Ouverture, who was taken to France and killed, but L’Ouverture’s more radical followers annihilated the French army and declared their independence as a new republic, Haiti.

The Haitians’ bloody victory had important consequences for the United States as well. Stopped from moving on to New Orleans, Napoleon decided to sell the Louisiana Territories to Jefferson, who thus stood to benefit from the Haitian freedom fighters whom Jefferson had sold out. Still fearing the spread of black revolution, Jefferson also organized a blockade of Haiti, which helped drive the war-torn country into a spiral of violence and poverty that it has never escaped.

Faced with the opportunity to double the size of the United States, Jefferson recognized that there was no specific language in the Constitution covering such an opportunity, making the deal unconstitutional under Jefferson’s supposedly inviolable principle of “strict construction.” But suddenly recognizing the wisdom of the Federalists in inserting the flexible language on congressional powers, Jefferson went ahead with the purchase.

This vast new territory also opened up huge opportunities for Southern slaveholders, especially because the Constitution allowed the end of slave importation in 1808, meaning that the value of the domestic slave trade skyrocketed. That was especially important for established slave states like Virginia where the soil for farming was depleted.

Breeding slaves became a big business for the Commonwealth and enhanced Jefferson’s personal net worth, explaining his notations about valuing female “breeder” slaves even above the strongest males.

Inviting the Civil War

But the danger to the nation was that spreading slavery to the Louisiana Territories and admitting a large number of slave states would worsen tensions between North and South.

As Miller wrote, “Jefferson might have averted the struggle between the North and South, free and slave labor, for primacy in the national domain the immediate, and probably the only truly irrepressible, cause of the Civil War. Instead, Jefferson raised no objections to the continued existence of slavery in the Louisiana Purchase.

“Had he the temerity to propose that Louisiana be excluded from the domestic slave trade he would have encountered a solid bloc of hostile votes from south of the Mason-Dixon line. Jefferson was fond of saying that he never tilted against windmills, especially those that seemed certain to unhorse him. Jefferson neither took nor advocated any action that would weaken slavery among the tobacco and cotton producers in the United States.”

Indeed, keeping the new territories and states open to slavery became a major goal of Jefferson as President and after he left office.

Miller wrote, “In the case of the federal government, he could easily imagine circumstances perhaps they had already been produced by John Marshall which justified secession: among them was the emergence of a central government so powerful that it could trample willfully upon the rights of the states and destroy any institution, including slavery, which it judged to be immoral, improper, or inimical to the national welfare as defined by Washington, D.C.

“Confronted by such a concentration of power, Jefferson believed that the South would have no real option but to go its own way.”

Miller continued, “As the spokesman of a section whose influence was dwindling steadily in the national counsels and which was threatened with the ‘tyranny’ of a consolidated government dominated by a section hostile to the institutions and interests of the South, Jefferson not only took the side of slavery, he demanded that the right of slavery to expand at will everywhere in the national domain be acknowledged by the Northern majority.”

In the last major political fight of his life, Jefferson battled Northern efforts to block the spread of slavery into Missouri. “With the alarm bell sounding in his ears, Jefferson buckled on the armor of Hector and took up the shield of states’ rights,” wrote Miller. “Jefferson, in short, assumed the accoutrements of an ardent and an uncompromising champion of Southern rights. Possessed by this martial spirit, Jefferson now asserted that Congress had no power over slavery in the territories.

“Now he was willing to accord Congress power only to protect slavery in the territories and he converted the doctrine of states’ rights into a protective shield for slavery against interference by a hostile federal government. He was no longer concerned primarily with civil liberties or with the equalization of the ownership of property but in insuring that slave-owners were protected in the full plentitude of their property rights.

“The Missouri dispute seemed to mark the strange death of Jeffersonian liberalism.”

Rationalizing Slavery

Jefferson’s fight to extend slavery into Missouri also influenced his last great personal achievement, the founding of the University of Virginia. He saw the establishment of a first-rate educational institution in Charlottesville, Virginia, as an important antidote to elite Northern schools influencing the Southern aristocracy with ideas that could undermine what Jefferson dubbed “Missourism,” or the right of all states carved from the Louisiana Territories to have slavery.

Jefferson complained that Southern men, who traveled North for their college education, were infused with “opinions and principles in discord with those of their own country,” by which he meant the South, Miller wrote, adding:

“Particularly if they attended Harvard University, they returned home imbued with ‘anti-Missourism,’ dazzled by the vision of ‘a single and splendid government of an aristocracy, founded on banking institutions and moneyed corporations’ and utterly indifferent to or even contemptuous of the old-fashioned Southern patriots who still manned the defenses of freedom, equality, and democracy” — revealing again how words in Jefferson’s twisted world had lost all rational meaning.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 that barred slavery in new states north of the 36-degree-30 parallel “made the creation of such a center of learning imperative” to Jefferson, wrote Miller, thus driving his determination to make the University of Virginia a Southern school that would rival the great colleges of the North and would train young Southern minds to resist federal “consolidationism.”

Even Jefferson-admiring Meacham noted the influence of the Missouri dispute in Jefferson’s zeal to launch his university in Charlottesville. “The Missouri question made Jefferson even more eager to get on with the building of the University of Virginia for he believed the rising generation of leaders should be trained at home, in climes hospitable to his view of the world, rather than sent north,” Meacham wrote.

In short, Jefferson had melded the twin concepts of slavery and states’ rights into a seamless ideology. As Miller concluded, “Jefferson began his career as a Virginian; he became an American; and in his old age he was in the process of becoming a Southern nationalist.”

When he died on July 4, 1826, a half century after the Declaration of Independence was first read to the American people, Jefferson had set the nation on course for the Civil War.

However, even to this day, Jefferson’s vision of “victimhood” for white Southerners seeing themselves as persecuted by outside forces yet blinded to the racist cruelty that they inflict on blacks remains a powerful motivation for white anger, now spreading beyond the South.

We see Jefferson’s troubling legacy in the nearly deranged hatred directed at the first African-American president and in the unbridled fury unleashed against the federal government that Barack Obama heads.

In that sense, Thomas Jefferson could be called the intellectual father of today’s Tea Party movement and the antithesis of his own most noble words.

Investigative reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his new book, America’s Stolen Narrative, either in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com). For a limited time, you also can order Robert Parry’s trilogy on the Bush Family and its connections to various right-wing operatives for only $34. The trilogy includes America’s Stolen Narrative. For details on this offer, click here.

Very interesting article. I am reading the best and worst presidents. This is slightly off tanget. From what I know of John Adams, he would have been opposed to everything that Mr Parry wrote about. In fact they did not speak for years but then wrote a lot of letters to one another. I wonder how the reconciled their differences in order to have what was a friendly relationship.

From Mr. Parry’s observations, it isn’t hard to understand why the wealthy radicals of today are so drawn to Jefferson. He lived the lifestyle they all seek to emulate, especially owning slaves and using the female ones as his sex partners. The rules are only for those who don’t have the wealth to avoid their application.

This was an astounding read, much of it relatively common knowledge, yet some of it escaping widespread attention. I was particularly shocked over Jefferson’s ruthlessness in American foreign policy regarding Haiti. Then the open secret regarding the establishment of the University of Virginia as a counter-propaganda tool against Northern elite education was somewhat of an eye-opener. Jefferson remains a man deserving of some respect, but as with all the founding fathers, and virtually any human you can name, underneath the superficial virtuous portrayal lies controversy.

Thank you for your brilliant work, Mr. Parry.

” virtually any human you can name, underneath the superficial virtuous portrayal lies controversy”

Controversy? My foot! The man was hypocrisy personified, and a psychopath to boot. A fitting descendant of a “transported” English Felon.

This critical approach to Jefferson is very interesting, but I suggest at least these contrary notes:

1. Jefferson was suspected of sex with the slave Hemings because some of his descendants have a genotype sharing some African negro elements. But it was found that Jefferson’s ancestors have the same genetic elements, present also in some North African whites. The sources of the Meacham/Wiencek contemporary accounts should be examined critically also, to avoid using any exploitation of slander based upon modern or contemporary political motives.

2. Without rationalizing slavery or economic exploitation, it must be admitted that the pre-war South was in a difficult situation not relieved by the North. The solution was easy in principle but not in that situation. Because the abolitionists were almost entirely in the North and England, which also were the consumers of most of the slave cotton product, they were going to pay for the wage labor eventually. But no southerner could unilaterally convert to wage labor and compete with slave cotton. They also genuinely believed on some (disputable) evidence that it was impossible to run their economy with wage labor, and the North never seriously proposed a viable transition plan. And like any other race enslaved at that point in cultural/historical development in an economy unknown to their prior culture, the slaves were not readily imagined as independent citizens forming a reliable labor force. So there is a lot of apparently-compelling circumstance behind the Southern cause, and the North did not lead the way to a viable solution, nor even propose one. The North demanded abolition without compensation despite the Constitutional safeguards of property. Such means as inspecting all plantations and stamping slave-labor cotton to support a consumer tax paying slave wages (during an incentivized transition), would have required a large intrusive agency unthinkable at the time. But potentially viable solutions were never considered seriously to my knowledge, a fault of both North and South. The free state – slave state issues and failed compromises, and ultimately the Civil War, derive from this failure of the federal government to resolve these regional issues. I speculate that the spirit of compromise failed after the War of 1812, which removed the danger of invasion.

You have taken “intellectually dishonest sophistry” to a new level. Maybe you need some one to get you a piece of the Moon to prove that it is not made of green cheese.

Propaganda to legitimize another elitist mason that really did’nt give a rats butt who won because he would have had more power if the brits won but less money slaves ect.He was paid along with franklin a generals salary when overseas.obombba used the same koran as jefferson to be sworn into office.Do you see a pattern