In his State of the Union, President Obama vowed to continue the withdrawal of U.S. combat troops from Afghanistan, much as he did in Iraq. But his reliance on lethal drone attacks to kill suspected terrorists has raised many other concerns, as Bill Moyers and Michael Winship note.

By Bill Moyers and Michael Winship

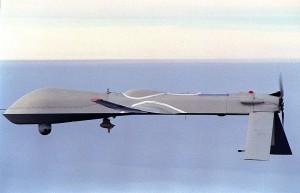

Last week, The New York Times published a chilling account of how indiscriminate killing in war remains bad policy even today. This time, it’s done not by young GIs in the field but by anonymous puppeteers guiding drones that hover and attack by remote control against targets thousands of miles away, often killing the innocent and driving their enraged and grieving families and friends straight into the arms of the very terrorists we’re trying to eradicate.

The Timestold of a Muslim cleric in Yemen named Salem Ahmed bin Ali Jaber, standing in a village mosque denouncing al-Qaeda. It was a brave thing to do, a respected tribal figure, arguing against terrorism. But two days later, when he and a police officer cousin agreed to meet with three al-Qaeda members to continue the argument, all five men, friend and foe, were incinerated by an American drone attack.

The killings infuriated the village and prompted rumors of an upwelling of support in the town for al-Qaeda, because, the Times reported, “such a move is seen as the only way to retaliate against the United States.”

Our blind faith in technology combined with a false sense of infallible righteousness continues unabated. Reuters correspondent David Rohde recently wrote:

“The Obama administration’s covert drone program is on the wrong side of history. With each strike, Washington presents itself as an opponent of the rule of law, not a supporter. Not surprisingly, a foreign power killing people with no public discussion, or review of who died and why, promotes anger among Pakistanis, Yemenis and many others.”

Rohde has firsthand knowledge of what a drone strike can do. He was kidnapped by the Taliban in 2008 and held for seven months. During his captivity, a drone struck nearby.

“It was so close that shrapnel and mud showered down into the courtyard,” he told the BBC last year. “Just the force and size of the explosion amazed me. It comes with no warning and tremendous force. There’s sense that your sovereignty is being violated. It’s a serious military action. It is not this light precise pinprick that many Americans believe.”

A special report from the Council on Foreign Relations last month, “Reforming U.S. Drone Strike Policies,” quotes “a former senior military official” saying, “Drone strikes are just a signal of arrogance that will boomerang against America.”

The report notes that, “The current trajectory of U.S. drone strike policies is unsustainable without any meaningful checks, imposed by domestic or international political pressure, or sustained oversight from other branches of government, U.S. drone strikes create a moral hazard because of the negligible risks from such strikes and the unprecedented disconnect between American officials and personnel and the actual effects on the ground.”

Negligible? Such hubris brought us to grief in Vietnam and Iraq and may do so again with President Obama’s cold-blooded use of drones and his indifference to so-called “collateral damage,” grossly referred to by some in the military as “bug splat,” and otherwise known as innocent bystanders.

Yet the ease with which drones are employed and the lower risk to our own forces makes the unmanned aircraft increasingly appealing to the military and the CIA. We’re using drones more and more; some 350 strikes since President Obama took office, seven times the number that were authorized by George W. Bush. And there’s a whole new generation of the weapons on the way, deadlier and with greater endurance.

According to the CFR report, “Of the estimated three thousand people killed by drones the vast majority were neither al-Qaeda nor Taliban leaders. Instead, most were low-level, anonymous suspected militants who were predominantly engaged in insurgent or terrorist operations against their governments, rather than in active international terrorist plots.”

By the standards of slaughter in Vietnam, the deaths caused by drones are hardly a bleep on the consciousness of official Washington. But we have to wonder if each innocent killed, a young boy gathering wood at dawn, unsuspecting of his imminent annihilation; a student who picked up the wrong hitchhikers; that tribal elder arguing against fanatics, doesn’t give rise to second thoughts by those judges who prematurely handed our President the Nobel Prize for Peace. Better they had kept it on the shelf in hopeful waiting, untarnished.

Bill Moyers is managing editor and Michael Winship, senior writing fellow at the think tank Demos, is senior writer of the weekly public affairs program, Moyers & Company, airing on public television. Check local airtimes or comment at www.BillMoyers.com.

Incontinent reader, I too agree. Assange did nothing to injure our national security nor did he release any truly secret documents, at least not to my knowledge anyway. Manning’s a psychological basket case and this condition persisted long before his arrest, detention and prosecution for allegedly releasing secret information, none of which, inflicted any harm to our troops. Nor can his actions be linked to a single field operative’s or paramilitary death(s). Obama should give him a free pass to a nice “farm” where he, Manning can recover his wits. Further, if he fomented anything it was a personal guilt that few of us can carry without cracking up. In our gut reaction(s) the Consortium readers know this to be true.

I completely agree.

So, after so many months of onsite reporting by Jeremy Scahill, and advocacy with additional documentation by CODEPINK, and finally a formal report by the Stanford and NYU Law Schools, the NYTimes is now starting to get it and get with it. The Times does still have some influence, since many of its readers only believe it when the Times reports it, but it is time for it to come out of its corporate shell and report more of the truth. Yet, one wonders if it has gotten enough of the message to begin reporting on the Hedges-Ellsberg NDAA case, or on the Manning case, and if they will finally acknowledge the value of Wikileaks and begin to advocate for Assange instead of discrediting him once they had cashed in big time on the documents Wikileaks released to it and the Guardian.