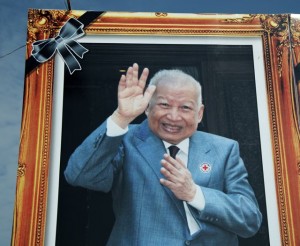

Exclusive: In an elaborate cremation ceremony, Cambodians bade farewell to their dead king, Norodom Sihanouk, the crafty leader who for decades tried to maneuver the small country around the interests of great powers, with mixed and sometimes disastrous results, reports Don North from Phnom Penh.

By Don North

Few monarchs have embraced the life and times of their country more dramatically than did King Norodom Sihanouk of Cambodia, whose earthly remains were cremated Monday while over a million of his former subjects watched in awe and devotion.

As fireworks lit the evening sky over Phnom Penh and an artillery salute echoed through the streets, the King’s son Sihamoni and the Queen mother Monineath lit the gas jets whose fire would consume the bier of the deceased monarch.

Sihanouk died of a heart attack three months ago in Beijing after a long illness just two weeks before his 90th birthday. He held so many positions of power in his lifetime that the Guinness Book of World Records identifies him as the politician who has served the world’s greatest variety of offices.

He served as King twice, Prince twice, once as President, twice as Prime Minister, leader of various governments-in-exile and head of state for the Khmer Rouge. Politically, he also served or opposed the various foreign and internal forces that controlled or sought to control Cambodia since the days of World War II,

Sihanouk began his government career in 1941 at age 18 as the puppet king chosen by the French colonial masters. But he showed his guile and nationalist fervor by outfoxing the French and leading Cambodia to independence without a military bloodbath as was experienced by neighboring Laos and Vietnam.

“The French chose me because they thought I was a lamb,” Sihanouk wrote. “But they found out I was a tiger.”

When the Vietnam War threatened to become a regional conflict Sihanouk tried to achieve neutrality, but he made choices and alliances that ultimately embroiled Cambodia in the war. He let the North Vietnamese establish bases along the border with South Vietnam, leading to massive American bombing, the destabilization of Cambodia and the eventual takeover by the radical Khmer Rouge whose brutality was blamed for the deaths of an estimated 1.7 million Cambodians.

How much responsibility did Sihanouk have for the disasters that struck Cambodia during his reign and for the imposition of the current repressive regime of Hun Sen today?

It’s a question being asked around the world, but not by many Cambodians as they bid farewell with great affection to Norodom Sihanouk whom many consider the last descendant of the God-Kings of Angor.

Pagoda built near the Royal Palace for the cremation ceremony of Norodom Sihanouk. (Photo credit: Don North)

Filming the Prince

I first met the then Prince Sihanouk in 1964 when I was assigned to direct a documentary on him by NDR German Television News. My TV crew and I followed him around Cambodia for a month much to his delight. Sihanouk always enjoyed the company of journalists and being interviewed.

A film producer himself Sihanouk often tried to advise me how to produce the documentary about him. He once showed me a film he produced and starred in as the intrepid detective Charlie Chan.

The last day of our tour with him was in Kampong Cham where he was to present medals to local officials. He found himself with several medals left over and said, “Mr. Don, here’s a medal for you too, for friendship to my country.”

The Prince loved to entertain his subjects when on tour and would play and sing songs that he had composed in Khmer, French and English. He had a passion for cinema, art, theatre and dance.

Sihanouk reportedly had several wives and concubines, producing at least 14 children. Five of his children were killed by the Khmer Rouge. His oldest surviving son. Norodom Sihamoni, 59, has now inherited his fathers title as King. His mother is Monique Izzi, the child of a French father and Cambodian mother.

Sihanouk married her in 1955 after awarding her a prize at a beauty contest. She was his constant companion and adviser ever since and is now referred to as the Queen Mother Monineath.

With carefully coiffed gray hair, she bears an amazing resemblance to Queen Elizabeth of England. Her only surviving son is King Norodom Sihamoni, his father’s choice to succeed him.

Sihamoni is a tall gentle man who studied ballet in Prague for 25 years and speaks fluent Czech. He is unmarried and is believed by many to be gay. By most accounts, he ascended the throne reluctantly and does not appear to have inherited his father’s political skills needed in the deadly political climate of Cambodia.

Several years ago, Sihanouk spoke out for the rights of gays and lesbians in a country little known for civil rights. “I am not gay, but I respect the rights of gays and lesbians,” he said. “It’s not their fault if God makes them born that way.”

Legislation is pending in Cambodia to legalize same-sex marriage. To date, Sihamoni has shown little desire to expand his role staying in the background while his father was alive. Hun Sen has effectively silenced the new King by forbidding him to do interviews or make foreign trips. An invitation to visit the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C. was recently not accepted.

King Sihamoni and the widow Queen mother Monineath have led the mourning for Sihanouk visiting his cremation site regularly as Cambodian TV broadcasts followed their every move. They are tragic figures often seen weeping and comforting each other.

Cambodians are asking if Sihamoni with his mother’s support might now begin to act like a king following his father’s cremation. Hun Sen is said to have sworn a sacred oath before Sihanouk’s corpse to protect the monarchy, but there is little evidence that he will relinquish any of the power he has gained over 28 years since defecting from the Khmer Rouge and becoming leader of the ruling Cambodian Peoples Party (CCP), the former communist party.

The leader of the opposition party Sam Rainsy, now in exile, would face jail if he tried to return to Cambodia. Hun Sen is said to be grooming his three sons for power, which is already shared with his family. Hun Sen’s eldest son is a two-star general, his brother a provincial governor, a nephew the national police chief and his family, relatives and friends controlling vast real estate and business enterprises.

Bridges, schools and roads across the country bear Hun Sen’s name or that of his powerful wife Bun Rany.

Hun Sen’s Kleptocracy

Cambodians whom I have met during the days of funeral ceremonies express little respect for Hun Sen’s power or the “kleptocracy” Cambodia has become under his rule and the clique of former communist Khmer Rouge apparatchiks.

I have always found the taxi drive from an airport a good place to get the latest news on which way the wind is blowing with the common man and that old journalistic truism remains in force.

“Hun Sen is selling Phnom Penh real estate and even people’s farm land to Korean, Russian and Chinese millionaires and pocketing most of the money,” my youthful taxi driver told me in perfect English that he had learned from tourists.

“While they get rich and drive big cars, we have to pay bribes for a doctor’s care and even our children must bring bribes to the teacher every morning. Whatever else he did, nobody ever accused our father-king Sihanouk of corruption.”

Sihanouk’s funeral comes at a time of relative stability in Cambodia and rising prosperity in the capital, Phnom Penh. It’s a city with skyscrapers popping up, glitzy shopping malls and restaurants replacing the French colonial architecture and tree-shaded streets.

But economic growth has passed by the countryside, where the majority of the 13 million people live. Only a quarter of Cambodians have access to electricity and about a third of homes have no running water.

Last Thursday, four days of funeral ceremony began with an exotic procession of marching groups, chanting Buddhist monks, military formations and gamelon orchestras. An estimated one million citizens lined the streets to pay their respects as an elaborate chariot carried the body of the dead King along the six-kilometer route from the Royal Palace to an elaborate pagoda built to facilitate the cremation.

For four days Cambodians in long lines filed past the King’s body lying in state. They burned joss sticks and candles in front of the Royal Palace.

Monday afternoon, a dozen heads of state, including the Prime Minister of Thailand and French Prime Minister, assembled for the King’s cremation. The United States was represented by Ambassador William E. Todd. Many Cambodians were reported upset when US President Barack Obama was one of the only leaders attending a regional meeting here last November who did not pay his respects before Sihanouk’s remains.

Sihanouk’s Legacy

My friend Jim Pringle, who for most of his life covered the war in Vietnam and Cambodia for Reuters, has probably interviewed Sihanouk more times than any other foreign journalist. In his last interview, Sihanouk told Pringle, “ I have no remorse. I always did everything in the highest interest of my nation, my conscience is clear.”

Jim Pringle, who has lived in Phnom Penh for the last several years, says he believes history will judge Sihanouk favorably. “I’m sure to his allies Sihanouk was exasperating and no doubt he has been an autocratic ruler. But I’ve known Cambodia under several regimes and the Khmer Rouge: there’s no doubt his time in power was a golden age for Cambodia.

“How can you look at the mystic insanity of Lon Nol [the U.S.-backed leader who replaced Sihanouk], or crimes against humanity of the vicious Khmer Rouge [who replaced Lon Nol] or the bullying and land grabbing of the current bunch and say otherwise.

“Sihanouk’s time was the best for Cambodia in recent history. He brought the country to peaceful independence and kept it out of the bloody conflict in Vietnam as long as he could. There will never be another Sihanouk. He was an original.”

The outpouring of grief and displays of devotion by many Cambodians since the death of Norodom Sihanouk has seemed to connect them with a better past and, they hope, a bridge to a better future. With the cremation ceremony over with some of the King’s ashes cast into the confluence of the Mekong and Tonle Sap rivers and others preserved in a golden urn to be stored in the Royal Palace Cambodians will turn to upcoming national elections, which Hun Sen is certain to win again.

Don North has been a war correspondent since covering Vietnam beginning in 1965.

Show Comments