From the Archive: The U.S. political/media world often operates without justice. Truth-tellers get punished and the well-connected get off. On this eighth anniversary of journalist Gary Webb’s suicide, we are re-posting one of the stories that Webb’s brave work forced out, albeit without a satisfying ending.

By Robert Parry (Originally published on Aug. 2, 1998)

John Hull, the American farmer in Costa Rica whose land became a base for Contra raids into Nicaragua, averted prosecution for alleged drug trafficking by fleeing Costa Rica in 1989 with the help of U.S. government operatives.

A 1998 report by Justice Department Inspector General Michael Bromwich disclosed that Hull escaped from Costa Rica in a plane flown by a pilot who worked for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. The report, however, could not reconcile conflicting accounts about the direct involvement of a DEA officer and concluded, improbably, with a finding of no wrongdoing.

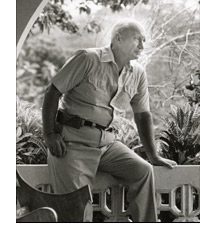

John Hull, an American farmer in Costa Rica who worked closely with the Nicaraguan Contras in the 1980s.

The finding makes Bromwich’s report one more chapter in a long saga of U.S. government protection of Hull, a fervent anti-communist who became a favorite of the Reagan-Bush administrations. (Bromwich’s disclosure regarding Hull’s escape was one of many that resulted from federal investigations prompted by a 1996 investigative series in the San Jose Mercury News written by Gary Webb.)

For years, Contra-connected witnesses had cited Hull’s ranch as a cocaine transshipment point for drugs heading to the United States. According to Bromwich’s report, the DEA even prepared a research report on the evidence in November 1986. In it, one informant described Colombian cocaine off-loaded at an airstrip on Hull’s ranch. The drugs were then concealed in a shipment of frozen shrimp and transported to the United States, the informant said.

The alleged Costa Rican shipper was Frigorificos de Puntarenas, a firm controlled by Cuban-American Luis Rodriguez. Like Hull, however, Frigorificos had friends in high places. In 1985-86, the State Department had selected the shrimp company to handle $261,937 in non-lethal assistance earmarked for the Contras. In 1987, the DEA in Miami opened a file on Rodriguez, but soon concluded there was no case.

However, as more evidence surfaced in 1987, the FBI and Customs indicted Rodriguez for drug trafficking and money-laundering. But Hull remained untouchable, although five witnesses implicated him during Sen. John Kerry’s investigation of Contra-drug trafficking. The drug suspicions just glanced off the pugnacious farmer, who had cultivated close relationships with the U.S. Embassy and conservative Costa Rican politicians.

In January 1989, however, Costa Rican authorities finally acted. They indicted Hull for drug trafficking, arms smuggling and other crimes. Hull was jailed, a move that outraged some U.S. congressmen. A letter, signed by Rep. Lee Hamilton, a senior Democrat on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and other members, threatened to cut off U.S. economic aid if Hull were not released.

[In a 1992 congressional investigation, Hamilton also played a central role in covering up evidence of Republican collaboration with Iran during the 1980 hostage crisis. See Robert Parry’s America’s Stolen Narrative.]

Costa Rica complied, freeing Hull pending trial. But Hull didn’t wait for his day in court. In July 1989, he hopped a plane, flew to Haiti and then to the United States. Hull got another break when one of his conservative friends, Roberto Calderon, won the Costa Rican presidency. On Oct. 10, 1990, Calderon informed the U.S. embassy that he could not stop an extradition request for Hull’s return but signaled that he did not want to prosecute his pal.

The embassy officials got the message and fired off a cable noting that the new president was “clearly hoping that Hull will not be extradited.” President George H.W. Bush’s administration fulfilled Calderon’s hope by rebuffing Costa Rican extradition requests, effectively killing the case against Hull.

DEA Airways

While not objecting to that maneuvering, Bromwich’s report revealed that behind the scenes, another drama was playing out: an internal investigation into whether DEA personnel had conspired to thwart Hull’s drug prosecution.

That phase of the story began on May 17, 1991, when a Costa Rican journalist told a DEA official in Costa Rica that Hull was boasting that a DEA special agent had assisted in the 1989 flight to Haiti. DEA launched an internal inquiry, headed by senior inspector Anthony Ricevuto.

The suspected DEA agent, whose name was withheld in Bromwich’s report, admitted knowing Hull but denied helping him escape. Inspector Ricevuto learned, however, that one of the agent’s informants, a pilot named Harold Wires, had flown the plane carrying Hull.

When interviewed on July 23, 1991, Wires said the DEA agent had paid him between $500 and $700 to fly Hull to Haiti aboard a Cessna. In Haiti, Wires said, they met another DEA pilot Jorge Melendez and Ron Lippert, a friend of the DEA agent; Melendez accompanied Wires back to Costa Rica; and Lippert flew with Hull to the United States.

From DEA records, Ricevuto confirmed that Melendez had been a DEA informant and freelance pilot. But when questioned, Melendez denied seeing Hull in Haiti. Then, 20 days later, Ricevuto got a call from Wires who reversed his initial story. Wires suddenly was claiming that the DEA agent did not know that Hull was on the Cessna.

Later, Wires amended the story again, saying that the agent gave him $700 to pay for the Cessna’s fuel but only for the return flight. Wires also claimed it was the agent’s friend, Lippert, who asked Wires to fly Hull out of Costa Rica, not the agent. Wires added that he took the assignment because he felt the CIA had abandoned Hull. Yet, Wires also acknowledged that he had received an angry call from Hull who wanted to clear the agent of suspicion.

Though Hull’s overheard comments about the DEA agent’s role had started the investigation, Hull weighed in on Oct. 7, 1991, with a letter. “I have no idea if [the accused agent] knew how and when I was leaving Costa Rica,” Hull wrote. He then added, cryptically, “I assumed the ambassador was fully aware of my intentions.”

For his part, Lippert told Inspector Ricevuto that the DEA agent indeed had helped plan Hull’s escape. But a DEA polygrapher was brought in to test Lippert and judge him “deceptive.” No polygraphs apparently were ever administered to Wires, Hull or the DEA agent.

So, despite the evidence that DEA personnel conspired in the flight of an accused drug trafficker, the DEA cleared the agent of any wrongdoing. Bromwich endorsed that finding as “reasonable.”

Investigative reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his new book, America’s Stolen Narrative, either in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com).

Show Comments