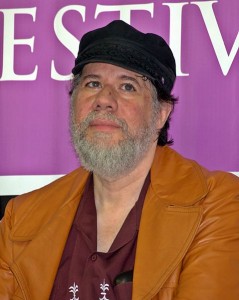

The challenge of poetry in a time of professional euphemism is to reconnect words to reality, a nearly subversive concept in an age when rich investors and bottom-line executives have been transformed into “job-creators.” Martin Espada is one poet who has taken on the task, as Dennis J. Bernstein explains.

By Dennis J. Bernstein

For me, Martin Espada’s poetry is transcendent and very precise at the same time. His poems are an act of love at every turn, and do bear witness in a way that is poignant and unforgettable.

Called “theLatino poet of his generation,” MartÃn Espada was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1957. He has dedicated much of his career to the pursuit of social justice, including fighting for Latino rights and reclaiming the historical record. Espada’s critically acclaimed collections of poetry celebrate, and lament, the immigrant and working class experience.

Whether narrating the struggles of Puerto Ricans and Chicanos as they adjust to life in the United States, or chronicling the battles Central and South Americans have waged against their own repressive governments, Espada has put “otherness,” powerlessness, and poverty, into poetry that is at once moving and exquisitely imagistic.

“Espada’s books have consistently contributed to unglamorous histories of the struggle against injustice and misfortune,” noted David Charlton in the National Catholic Reporter.

Espada is the winner of many awards, including the 2012 Milton Kessler Award and the 2012 International Latino Poetry Award for his collection of poems, “The Trouble Ball.” Espada’s collection “The Republic of Poetry” was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

His other collections include “A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen,” “Imagine the Angels of Bread,” “City of Coughing,” “Dead Radiators,” and “Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands.” One reviewer has written about “The Trouble Ball”: “This is what the poetry of witness must dare to do.”

Espada discussed his life and work in an interview on “Flashpoints”:

DB: Well, it is good to have you with us, and it’s good to have you on this planet. We need a poet to sort of tell all of our stories and we’re going to spend most of the time on the poetry, and celebrate the release, in paperback, of “The Trouble Ball.”

But I want to start with your banning, … the banning of your book of essays, banned in Tucson, along with, essentially the purging of Ethnic Studies, the Mexican American Studies Program. The collection, “Zapata’s Disciple” obviously made the list, and I wanted to talk to you a little bit about it.

You write a bit about it at The Progressive web site. And you point out that you’ve had sort of a bit of a history on being censored, if you will, and a bit of a history in Tucson. You want to talk about that? [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Banning Books in Tuscon.“]

ME: Yes. Well, when this book “Zapata’s Disciple” was banned in Tucson my first reaction was “Again?” Because this wasn’t the first time that I’ve been censored and it wasn’t even the first time this particular book has been banned.

“Zapata’s Disciple,” which is a collection of essays and poems from South End Press, was actually banned once before, by the Texas state penal system. The publisher actually attempted to donate this book to the Texas penal system so that inmates in Texas might read it.

A committee of some sort convened and decided that this was a book that could not be allowed into the prison system in Texas. They actually sent back a form with a couple of boxes checked stating the reasons why. Apparently, one of the reasons was that this book might lead to the incitement of rioting among the inmates.

There was also a citation of the use of racial slurs in the book. I was rather astonished by this, because I could not remember using racial slurs against anyone, much less in my own book. So I actually looked up the page that was cited and it was a reference to racial slurs used against me, in my childhood.

So it was a creative spin there, and, but then, you know, there is a kind of perverse creativity to censorship and book banning wherever you find it.

Certainly we find it in Arizona, with the banning of Ethnic Studies, the banning of the Mexican-American Studies Program, in Tucson, particularly, and the banning of a number of books.

Of course, we should be clear it wasn’t only “Zapata’s Disciple” that was banned and literally taken out of the classroom there in Tucson. It is a roll of honor if you look at some of the other authors who were banned there: James Baldwin, and Howard Zinn, and César Chávez, and Ana Castillo, and Sandra Cisneros, and Sherman Alexie, and the list goes on, and on, and on.

So I am in very good company. I’m glad and proud to be there. But, of course, once you get over that “not again” sensation, and once you get over that sense of pride in belonging to a pretty select group of writers, you start to reflect that you live in a country where book banning is going on, where it’s going on openly. And here’s the funny part: not too many people are upset about it.

Now I realize that you, Dennis, at KPFA, have been tracking this story for a long time, and The Progressive magazine as well, has been tracking this story for a long time. I found out about it from reading The Progressive magazine’s web site. I discovered that my book had been banned. It was on this list of books from the curriculum of the Mexican-American Studies Program that itself had been banned in Tucson.

Now, my question is this: Where is the major media coverage of this act of censorship? … Let me qualify that: this act of racist censorship. Where’s the New York Times on this? You know, where’s NPR? Where is the nationwide outrage about this act of blatant book-banning in Tucson, Arizona? I don’t see it. Maybe I’m missing something. Am I missing something?

DB: I’m not sure you are missing anything. I am noticing a bit of history in you in Tucson, and I notice that you were to be reading, … you did read for Derechos Humanos in Tucson, where we have broadcast from over the years, from time to time. And you had a little problem there!

ME: Well, you know, I started making some connections in my mind when I found out that “Zapata’s Disciple” had been banned in Tucson. One of the connections I made was that there is an essay in the book called “The New Bathroom Policy at English High School,” which is all about language politics in the United States.

Mind you, it was written quite some time ago. This book of essays was actually published in 1998, but the issues are still very much the same. I’ll read from the tail end of that essay, because in fact it refers directly to the experience that you mentioned a moment ago.

I wrote here: The repression of Spanish is part of a larger attempt to silence Latinos, and like the crazy uncle at the family dinner table yelling about independence or socialism, we must refuse to be silenced.

On October 12th, 1996 — Columbus Day — I gave a reading at a bookstore in Tucson, Arizona. The reading was co-sponsored by Derechos Humanos, a group which monitors human rights abuses on the Arizona-México border, and was coordinated with the Latino March on Washington that same day.

At 7 PM, the precise time when the reading was to begin, we received a bomb threat. The police arrived with bomb-sniffing dogs, and sealed off the building. I did the reading in the parking lot, under a streetlamp. This is one of the poems I read that night, based on an actual exchange in a Boston courtroom. It’s a short bilingual poem called

Mariano Explains Yanqui Colonialism to Judge Collings

Judge: Does the prisoner understand his rights?

Interpreter: ¿Entiende usted sus derechos?

Prisoner: ¡Pa’l carajo! (which roughly translates, “go to hell!”)

Interpreter: Yes.

DB: Oh yeah. Well Martin, it’s really important to mention that this is not just the reactionary right wing. As you said, the New York Times hasn’t picked it up yet, and you did not mention that your work was also censored by NPR.

ME: Oh yes.

DB: The liberals are in this.

ME: The liberals are in this. And they’re usually in there somewhere, absolutely. Again, that’s a story that you, Dennis, covered as it happened all those years ago. I believe the year was 1997, and National Public Radio was in fact the place where my voice was heard for a number of years. Then I was commissioned by Weekend All Things Considered to be a kind of correspondent for them during National Poetry Month, in April of 1997. Everybody knows that National Poetry Month is in April, right?

Anyway, I was contacted by All Things Considered and they commissioned a poem from me. They basically said, “Since you’re traveling everywhere, be a roving correspondent and write something based on your travels: something you see, something you hear, something you read.” I did just that. I visited Philadelphia, and Camden, New Jersey. I visited the tomb of Walt Whitman in Camden.

I began making some connections with the case of Mumia Abu-Jamal, the African-American journalist, convicted of killing a Philadelphia police officer named Daniel Faulkner, many, many years ago. And many of us, myself included, feel that he did not receive anything resembling a fair trial, and that he is imprisoned unjustly.

So I wrote a poem about Mumia Abu-Jamal, which tied in Walt Whitman and his tomb, and lots of other peculiarities. I presented it to NPR to Weekend All Things Considered and they were suitably horrified, and they refused to air the poem. I actually spoke to a junior producer who let the cat out of the bag. Not to reiterate that entire case, but she told me quite directly that this was a poem they would not air for political reasons.

Then they did a number of flip-flops and somersaults trying to justify their position. All of this ended up splattered across the newspapers and magazines over a period of about a year or so afterwards. There was a cover story in the Progressive: “All Things Censored: The Poem NPR Doesn’t Want you to Hear.”

That actually got a surprising amount of attention, considering just how controversial Mumia was, and is to this day. One of the surprises that I am now trying to turn over in my head is why there was such an uproar when my poem about Mumia Abu-Jamal was censored by National Public Radio, but an entire academic program, the Mexican American Studies Program in the Tucson Unified School District, has been censored and shut down in just the same way by the state of Arizona and there’s barely a peep.

I am, again, trying to figure out why we no longer, as a nation, even seem to make the attempt to live up to the rhetoric of free expression, the rhetoric of free speech, the rhetoric of academic freedom. You know, where is it?

DB: Well, that’s a good question. We’re going to keep pushing that envelope. We’re going to be, actually, going back to Tucson after the elections to do a lot more reporting on what’s been going on down there. There is a battle to un-ban the books and I’m sure you’ve heard about Librotraficante, and the trafficking of books back into Tucson, yours among them; more on that coming up.

We are delighted and honored to be talking to poet Martin Espada. His book “The Trouble Ball” was just reissued in paperback by Norton and we wanted to celebrate. There’s another opportunity to hear the great work of an important poet. Well, let me ask you, Martin Espada, what do you see as the work of a poet. Why is a poet important in the twenty-first century?

ME: I think the work of a poet is important in the twenty-first century, because at this stage of history we have reached such a gulf between language and the meaning of language. Let me expand on that a little bit.

We live in an age of hyper-euphemism. That’s why we can use language politically and bureaucratically the way that we do. This is why the government and the media and the educational system and big corporations use language in the way they do. Language is increasingly divorced from meaning. Increasingly, there’s a separation of words from what they actually mean. You know, it’s a tendency that’s been going on for a very long time. But now it’s been perfected.

We talk about “extraordinary rendition” when we refer to the kidnapping and the incarceration of people around the world by this government. And there are so many more euphemisms. We use language like “weapons of mass destruction” in order to justify a war. They never found the weapons of mass destruction, but the words themselves did damage enough.

So how does a poet fit into this equation? Well, if this kind of hyper-euphemism drains the blood from words, poets can restore the blood to words. They can reconcile language with meaning. They can say what they mean and in so doing create a record, bear witness, give testimony, speak clearly about what is happening, both for the present generations and the generations to come who want to know what really happened at the beginning of the twenty-first century.

I see that as something poets can do. In some respects, this is not a new idea. You can go back to Percy Bysshe Shelley, speaking of poets as the unacknowledged legislators of the world. You can go back to Walt Whitman, speaking of his role as a poet to advocate “for the rights of them the others are down upon,” to use his phrase.

I am part of that tradition and that continuum. It’s just that now we live in an age where language has been so depleted of its meaning, and so divorced from itself, that we as poets have to step into that breach.

DB: Well, let’s start at the front of the book, let’s start with the poem “The Trouble Ball,” which is essentially from the view of a child. But that child’s not you; that’s your father, Frank Espada. You want to set this up and read “The Trouble Ball” for us?

ME: Sure. My father, Frank Espada, was born in Utuado, Puerto Rico, in 1930. And my father loved baseball. Growing up on the island of Puerto Rico during the 1930s, his heroes were not only the ball players native to Puerto Rico but ball players who came from the Negro Leagues, and were most welcome on the island, in contrast to their treatment at that same time in the United States, where African-American players, and dark-skinned Latino players as well, were prohibited from playing major league baseball.

My father and his father particularly favored Satchel Paige, the great pitcher from the Negro Leagues who, some say, was the greatest pitcher of the twentieth century. There’s a good argument to be made for that. Satchel was not only a great pitcher, but something of a raconteur, a story teller. He had names for many of his pitches, and one of them was “The Trouble Ball.” That was his change-up, actually.

So my father and his family relocated to the United States, moving back and forth a couple of times. But they had settled in New York by the year 1941, and it was at that point that my father saw his first big-league ball game, at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

Now, of course, when we, with the benefit of historical hindsight, think about the Brooklyn Dodgers and Ebbets Field, we think of what? We think of Jackie Robinson, we think of integration, we think of this great social experiment. Of course, we tend to forget that all that happened in 1947. But in 1941, the year when this poem begins, Ebbets Field was just as segregated as any other ball park, and the Brooklyn Dodgers were just as segregated as any other baseball team.

So my father went with his father to see the Dodgers play the Cardinals at Ebbets Field on a beautiful day in 1941. My father was in for something of a shock there at the age of eleven, something that would not only impact on him and the way he saw the ball park, and the players, but the way he saw everything else too. This is a kind of baseball biography, if you will. Again, the poem is called

The Trouble Ball

For my father, Frank Espada

In 1941, my father saw his first big league ballgame at Ebbets Field

in Brooklyn: the Dodgers and the Cardinals. My father took his father’s hand.

When the umpires lumbered on the field, the band in the stands

with a drum and trombone struck up a chorus of Three Blind Mice.

The peanut vendor shook a cowbell and hollered. The home team

raced across the diamond, and thirty thousand people shouted

all at once, as if an army of liberation rolled down Bedford Avenue.

My father shouted, too. He wanted to see The Trouble Ball.

On my father’s island, there were hurricanes and tuberculosis, dissidents in jail

and baseball. The loudspeakers boomed: Satchel Paige pitching for the Brujos

of Guayama. From the Negro Leagues he brought the gifts of Baltasar the King;

from a bench on the plaza he told the secrets of a thousand pitches: The Trouble Ball,

The Triple Curve, The Bat Dodger, The Midnight Creeper, The Slow Gin Fizz,

The Thoughtful Stuff. Pancho CoÃmbre hit rainmakers for the Leones of Ponce;

Satchel sat the outfielders in the grass to play poker, windmilled three pitches

to the plate, and Pancho spun around three times. He couldn’t hit The Trouble Ball.

At Ebbets Field, the first pitch echoed in the mitt of Mickey Owen,

the catcher for the Dodgers who never let the ball escape his glove.

A boy off the boat, my father shelled peanuts, waiting for Satchel Paige

to steer his gold Cadillac from the bullpen to the mound, just as he would

navigate the streets of Guayama. Yet Satchel never tipped his cap that day.

¿Dónde están los negros? asked the boy. Where are the Negro players?

No los dejan, his father softly said. They don’t let them play here.

Mickey Owen would never have to dive for The Trouble Ball.

It was then that the only brown boy at Ebbets Field felt himself

levitate above the grandstand and the diamond, another banner

at the ballgame. From up high he could see that everyone was white,

and their whiteness was impossible, like snow in Puerto Rico,

and just as silent, so he could not hear the cowbell, or the trombone,

or the Dodger fans howling with glee at the bases-loaded double.

He understood why his father whispered in Spanish: everybody

in the stands might overhear the secret of The Trouble Ball.

At Ebbets Field in 1941, the Dodgers met the Yankees in the World Series.

Mickey Owen dropped the third strike with two outs in the ninth inning

of Game Four, flailing like a lobster in the grip of a laughing fisherman,

and the Yankees stamped their spikes across the plate to win. Brooklyn,

the borough of churches, prayed for his fumbling soul. This was the reason

statues of the Virgin leaked tears and the fathers of Brooklyn drank,

not the banishment of Satchel Paige to doubleheaders in Bismarck,

North Dakota. There were no rosaries or boilermakers for The Trouble Ball.

My father would return to baseball on 108th Street. He pitched for the Crusaders,

kicking high like Satchel, riding the team bus painted with four-leaf clovers, seasick

all the way to Hackensack or the Brooklyn Parade Grounds. One day he jammed

his wrist sliding into second, threw three more innings anyway, and never pitched again.

He would return to Ebbets Field to court my mother. The same year they were married

a waiter refused to serve them, a mixed couple sitting all night in the corner,

till my father hoisted him by his lapels and the waiter’s feet dangled in the air,

a puppet and his furious puppeteer. My father was familiar with The Trouble Ball.

I was born in Brooklyn in 1957, when the Dodgers packed their duffle bags

and left the city. A wrecking ball swung an uppercut into the face

of Ebbets Field. I heard the stories: how my mother, lost in the circles

and diamonds of her scorecard, never saw Jackie Robinson accelerate

down the line to steal home. I wore my father’s glove until the day

I laid it down to lap the water from the fountain in the park. By the time

I raised my head, it was gone like Ebbets Field. I walked slowly home.

I had to tell my father I would never learn to catch The Trouble Ball.

There was a sign below the scoreboard at Ebbets Field: Abe Stark, Brooklyn’s

Leading Clothier. Hit Sign, Win Suit. Some people see that sign in dreams.

They speak of ballparks as cathedrals, frame the pennants from the game

where it began, Dodger blue and Cardinal red, and gaze upon the wall.

My father, who remembers everything, remembers nothing of that dazzling day

but this: ¿Dónde están los negros? No los dejan. His hair is white, and still

the words are there, like the ghostly imprint of stitches on the forehead

from a pitch that got away. It is forever 1941. It was The Trouble Ball.

DB: That’s, obviously, the opening poem from the collection. And I just want to ask you a quick question about poetics and the way that you write. I think, I love how you include the linguistics of whatever it is, the sports, or the event, or the torture. You use…and why is that important? …naming the pitches.

ME: Well, I think it is important for poets to be precise. I also think it’s important for poets to use the vocabulary that’s available to them, depending on the subject at hand. Certainly, in this case, I am using a vocabulary that includes very particular references to places, and times, and pitches, and players. And that is a matter of being precise, which I think poets should be in all things. But it’s also a matter of capturing the music of that particular moment in history, catching the imagery of that particular moment in history, and doing it with the vocabulary of that time and place.

We are surrounded by poetry and don’t even know it. What poets do, of course, is very much akin to what birds do when they are feathering a nest. You take something from here, something from there, and in the end it becomes a poem.

So that’s what I’m trying to do here. What I want this poem to do is to resonate beyond the immediate subject, which, obviously, is baseball. But it’s not simply a baseball poem per se. “The Trouble Ball,” after all, represents a metaphor for the big trouble, which in this instance is racism. Right?

That’s the trouble in this poem. That’s the trouble for Satchel Paige. That’s the trouble for my father. That’s the trouble for all of us, to one degree or another, depending on who we are, where we are. “The Trouble Ball” begins on the most literal level as the pitch that Satchel Paige threw and named, and yet it is so much more in this poem.

DB: I tell you, Martin, I’ve read the book a couple of times. Usually I read a couple of poems at a time, but this morning I sat down, and I read it through, and I have to say it was an incredibly wonderful experience. And I spent my time somewhere between tears and exaltation. And one of the poems that really sort of brought it home — I have never had you read this on the air before — is “Isabel’s Corrido.” And please tell us about what a “corrido,” if I’m saying that right, and set this poem up and please read it.

ME: Of course. “Isabel’s Corrido,” first of all, is based on a true story. Secondly, there is a bit of Spanish vocabulary in the poem. A “corrido” is a Mexican narrative song. It’s a story-telling song, whether the subject is love or revolution. And there are a couple of other things as well. There’s a phrase here, “quiero ver las fotos” which simply means “I want to see the pictures.”

I also refer to “the land of Zapata.” Emiliano Zapata was one of the major leaders of the Mexican revolution of 1910. He came from the state of Morelos, which is the same place where Isabel was born. That’s the connection between them. I made reference to the fact that this is based on a true story. It comes from my own life, some thirty years ago.

There was a time when I couldn’t even talk about what happened to Isabel, much less write about it. But as I witnessed the increasing backlash in this country against immigrants and immigration, which has been going on and building in intensity for so many years, I felt I had no choice but to finally write this poem down and speak out.

It’s a very personal, very intimate poem at the same time it’s a very political poem. Even though it’s based on something that happened three decades ago, it is very much a response to what’s happening now with immigrants and immigration. And so I will, indeed, read the poem. It’s called

Isabel’s Corrido

For Isabel

Francisca said: Marry my sister so she can stay in the country.

I had nothing else to do. I was twenty-three and always cold, skidding

in cigarette-coupon boots from lamppost to lamppost through January

in Wisconsin. Francisca and Isabel washed bed sheets at the hotel,

sweating in the humidity of the laundry room, conspiring in Spanish.

I met her the next day. Isabel was nineteen, from a village where the elders

spoke the language of the Aztecs. She would smile whenever the ice pellets

of English clattered around her head. When the justice of the peace said

You may kiss the bride, our lips brushed for the first and only time.

The borrowed ring was too small, jammed into my knuckle.

There were snapshots of the wedding and champagne in plastic cups.

Francisca said: The snapshots will be proof for Immigration.

We heard rumors of the interview: they would ask me the color

of her underwear. They would ask her who rode on top.

We invented answers and rehearsed our lines. We flipped through

Immigration forms at the kitchen table the way other couples

shuffled cards for gin rummy. After every hand, I’d deal again.

Isabel would say: Quiero ver las fotos. She wanted to see the pictures

of a wedding that happened but did not happen, her face inexplicably

happy, me hoisting a green bottle, dizzy after half a cup of champagne.

Francisca said: She can sing corridos, songs of love and revolution

from the land of Zapata. All night Isabel sang corridos in a barroom

where no one understood a word. I was the bouncer and her husband,

so I hushed the squabbling drunks, who blinked like tortoises in the sun.

Her boyfriend and his beer cans never understood why she married me.

Once he kicked the front door down, and the blast shook the house

as if a hand grenade detonated in the hallway. When the cops arrived,

I was the translator, watching the sergeant watching her, the inscrutable

squaw from every Western he had ever seen, bare feet and long black hair.

We lived behind a broken door. We lived in a city hidden from the city.

When her headaches began, no one called a doctor. When she disappeared

for days, no one called the police. When we rehearsed the questions

for Immigration, Isabel would squint and smile. Quiero ver las fotos,

she would say. The interview was canceled, like a play on opening night

shut down when the actors are too drunk to take the stage. After she left,

I found her crayon drawing of a bluebird tacked to the bedroom wall.

I left too, and did not think of Isabel again until the night Francisca called to say: Your wife is dead. Something was growing in her brain. I imagined my wife

who was not my wife, who never slept beside me, sleeping in the ground,

wondered if my name was carved into the cross above her head, no epitaph

and no corrido, another ghost in a riot of ghosts evaporating from the skin

of dead Mexicans who staggered for days without water through the desert.

Thirty years ago, a girl from the land of Zapata kissed me once

on the lips and died with my name nailed to hers like a broken door.

I kept a snapshot of the wedding; yesterday it washed ashore on my desk.

There was a conspiracy to commit a crime. This is my confession: I’d do it again.

DB: MartÃn Espada reading from “The Trouble Ball.” And when did you write that?

ME: It was the last poem to go into the book.

DB: And did it take you a long time to write the poem? How long did it take you to make that poem?

ME: It didn’t take long to write this poem. It took many years to think about it. For many years I was turning this poem over in my head, trying to figure out the best way to approach it, trying to find the words to articulate it. Once it finally came time to sit down and write the poem, it didn’t take very long.

There weren’t that many drafts, although I do believe in revision, very much so. But this one was years and years in the making, so it’s kind of misleading to talk about how long it took to write it. It took a very long time to create.

DB: Well, I want ask you to read another poem. It’s called “The Hole in the Bathroom Ceiling.” And I have to admit when I started this live show, and we are live, I’m thinking to myself, “Well, poets have never been dissuaded from using linguistics that are not accepted in the mainstream. For instance, to this day we cannot read ‘Howl’ on the radio.”

ME: That’s right.

DB: But it occurs to me that I was worried about this poem. I had to look back because I was worried about language. One feels like you’re cursing all the way through it. Why don’t you read “The Hole in the Bathroom Ceiling?” And set that up.

ME: This is a poem, which, as the title implies, it is set in a bathroom, for the most part, and so there are vaguely “obscene” things going on in the poem. I guess the larger question is: “What is the obscenity?” This is, on the one hand, a poem about strange and silly things happening in my bathroom these things really did happen, by the way, and, on the other hand, this is very much a poem about economics. I’ll leave it to the listener to conclude how this is a poem about economics. The poem, again, is called

The Hole in the Bathroom Ceiling

I’ve seen holes in the ceiling:

in the kitchen ceiling, dripping percussive

rain into saucepans on the table;

in the living room ceiling, leaking

drops that burst between the eyes

of a visitor sitting on the couch;

in the bedroom ceiling, drizzling the spittle

onto the pillow that freezes overnight

and sticks to my head in the morning.

There is a hole in the bathroom ceiling bigger than my head.

God put the hole in the bathroom ceiling right over the toilet.

The plastic tacked over the hole flaps open, and a bounty

cascades from the heavens: the drywall soaked and crumbling

like a donut forgotten in a cup of coffee; the spiders swimming

to freedom that paddle happily, then panic and drown;

the mold that floats down into my lungs, where it will

strangle me in my sleep; the incontinence of rusted pipes

spraying in every direction. Everything tumbles

into the toilet, lid up, eager as the mouth

of a trained dolphin begging for fish at the aquarium.

For the hole right over the toilet, I fold my hands

and give thanks to God. I do not ruin saucepans

catching the rain, or befoul towels pushing them across

the floor with my feet, or fill pails that also leak.

Sometimes I must slam the plunger into the toilet,

eyes bulging with the fury of a sea captain harpooning

his nemesis the whale. Sometimes I open an umbrella

when I squat on the toilet. Sometimes I forget

till something cold and wet slaps the back of my neck.

Once a landlord tried to hand me an eviction notice. I chased him

back to his Toyota and kicked in the driver’s side door, a moose

enraged by the economy car that dared to bruise his knees.

The bank owns the house and the hole in the bathroom ceiling;

there is nowhere left to kick. Think of all the holes

in all the ceilings everywhere, and thank God.

DB: Would it be safe to say … would you believe that all poems are ultimately written out of a place of love, perhaps, and maybe a little anger, or what?

ME: Well, I think some poems are written out of love and anger. I think that last one certainly was. But not all poets and not all poems are created equal. And there is a political spectrum among poets, just as there is with everybody else. Let’s not forget that we’ve had our fair share of fascists in the wonderful world of literature. You know, we’ve been Ezra Pounded.

DB: Actually, you’ve got that little Ezra Pound poem. … Why don’t you throw that in here? It’s short and it makes this point.

ME: Yeah, well, I’ve got to find it. Here it is. This is a poem, one of two, in the book dedicated to a man by the name of Abe Osheroff. Abe Osheroff was a good friend of mine. He was born in 1915 and died in 2008. He was an activist for more than seventy years, an extraordinary record. He was a veteran of the Spanish Civil War. He went to Spain with the Lincoln Brigade to fight against fascism, as represented by Franco and Hitler and Mussolini.

So he had very strong opinions about literature and politics. I brought Abe to a place called the William Joiner Center for the Study of War and Social Consequences at U-Mass. Boston. There’s an annual writers conference there. I introduced Abe to a whole new generation of writers and veterans, and put him on a panel. This is what happened. This is literally what he said about Ezra Pound and the poem….

DB: Ezra Pound, of course, moved to Italy and was really a supporter of Mussolini essentially.

ME: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

DB: I want people to know that.

ME: Absolutely, yeah. Ezra Pound who was — and still is — in many quarters considered to be a major poet of the twentieth century, relocated to Italy, and not only made a number of radio broadcasts but did other things to speak for the fascists and Mussolini. After the war ended up committed to Saint Elizabeth’s in Washington, D.C., and many people feel that he staged his “insanity” to avoid being executed for treason. So now you’ve got a five-minute introduction to a ten-second poem

DB: Go for it.

How to Read Ezra Pound

At the poets’ panel,

after an hour of poets

debating Ezra Pound,

Abe the Lincoln veteran,

remembering

the Spanish Civil War,

raised his hand and said:

If I knew

that a fascist

was a great poet,

I’d shoot him

anyway.

DB: Ah yes, well listen, we have, MartÃn Espada, about ten minutes left and one poem I very much want to get to is in the context of your studying the work of Pablo Neruda, and the great poets of Chile. You spent some time there. And there’s an extraordinary poem — I hope I got this right — called “The Swimming Pool at Villa Grimaldi.”

ME: Okay. Now this is a heavy one. You sure you want me to read this?

DB: I do. Because I … you know there’s no curses in it. The whole thing is a curse on humanity, but I just think it’s an amazing poem. And it reminds us of a time we should not forget.

ME: Well, that time, in some ways is still upon us. I believe you are referring to the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet in Chile, from 1973 to 1990. During that time in Chile, of course, there were thousands killed and tens of thousands incarcerated and tortured.

It is remarkable to me that, in the present day, we in the United States. in the name of security, are debating the efficacy of torture: which torture works best and which torture is ethical and who to torture and who not to torture, and so on and so forth. As if you could have rules for this sort of thing. If anybody thinks that torture works as instrument of as social policy, all they have to do is look at the example of Chile, that traumatized and now transcendent nation.

I made two trips to Chile. The second one was in the spring of 2007. I visited a place called Villa Grimaldi. Now ,Villa Grimaldi, I should stress, was not a prison. It was a center of interrogation, torture and execution. It has now been restored as a peace park, but also a place of memorial. Many of the original features of Villa Grimaldi have been restored. Some of them are, in fact, original to Villa Grimaldi, including, to my astonishment, a swimming pool. So here we are with a prime example of “the banality of evil.” This poem is called

The Swimming Pool at Villa Grimaldi

Santiago, Chile

Beyond the gate where the convoys spilled their cargo

of blindfolded prisoners, and the cells too narrow to lie down,

and the rooms where electricity convulsed the body

strapped across the grill until the bones would break,

and the parking lot where interrogators rolled pickup trucks

over the legs of subversives who would not talk,

and the tower where the condemned listened through the wall

for the song of another inmate on the morning of execution,

there is a swimming pool at Villa Grimaldi.

Here the guards and officers would gather families

for barbeques. The interrogator coached his son:

Kick your feet. Turn your head to breathe.

The torturer’s hands braced the belly of his daughter,

learning to float, flailing at her lesson.

Here the splash of children, eyes red

from too much chlorine, would rise to reach

the inmates in the tower. The secret police

paraded women from the cells at poolside,

saying to them: Dance for me. Here the host

served chocolate cookies and Coke on ice

to the prisoner who let the names of comrades

bleed down his chin, and the prisoner

who refused to speak a word stopped breathing

in the water, facedown at the end of a rope.

When a dissident pulled by the hair from a vat

of urine and feces cried out for God, and the cry

pelted the leaves, the swimmers plunged below the surface,

touching the bottom of a soundless blue world.

From the ladder at the edge of the pool they could watch

the prisoners marching blindfolded across the landscape,

one hand on the shoulder of the next, on their way

to the afternoon meal and back again. The neighbors

hung bedsheets on the windows to keep the ghosts away.

There is a swimming pool at the heart of Villa Grimaldi,

white steps, white tiles, where human beings

would dive and paddle till what was human in them

had dissolved forever, vanished like the prisoners

thrown from helicopters into the ocean by the secret police,

their bellies slit so the bodies could not float.

DB: We have a couple of moments left, I guess about three minutes. Should we make this one the poet’s choice?

ME: The poet’s choice?

DB: Three minutes.

ME: Three minutes? Well, I have to look at my table of contents here. God only knows what I put in this book.

DB: What I love personally is “His Hands have Learned What Cannot be Taught.”

ME: All right.

DB: I’m sorry. I don’t want to jump in, but this is a beautiful poem and it’s about what happens at home.

ME: Yeah, you know, I see that one, and just at the very same moment there’s another one here that jumped out at me….

DB: Go for it. What have you got?

ME: I’ve got a poem here. Ah, you’re going to love this one.

DB: Okay, go.

ME: This is a poem about poetry and a poem about the discovery of poetry. I want to conclude with this poem because there’s some joy to it. I don’t want the listener to think that this book “The Trouble Ball” consists of one poem after another about torture and degradation. There’s more to it than that.

DB: There’s exaltation, there’s celebration of all kinds of people like Howard Zinn. Go for it.

ME: So here’s some exaltation. his is a poem called

The Playboy Calendar and the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám

The year I graduated from high school,

my father gave me a Playboy calendar

and the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.

On the calendar, he wrote:

Enjoy the scenery.

In the book of poems, he wrote:

I introduce you to an old friend.

The Beast was my only friend in high school,

a wrestler who crushed the coach’s nose with his elbow,

fractured the fingers of all his teammates,

could drink half a dozen vanilla milkshakes,

and signed up with the Marines

because his father was a Marine.

I showed the Playboy calendar to The Beast

and he howled like a silverback gorilla

trying to impress an expedition of anthropologists.

I howled too, smitten with the blonde

called Miss January, held high in my simian hand.

Yet, alone at night, I memorized the poet-astronomer

of Persia, his saints and sages bickering about eternity,

his angel looming in the tavern door with a jug of wine,

his battered caravanserai of sultans fading into the dark.

At seventeen, the laws of privacy have been revoked

by the authorities, and the secret police are everywhere:

I learned to hide Khayyám and his beard

inside the folds of the Playboy calendar

in case anyone opened the door without knocking,

my brother with a baseball mitt or a beery Beast.

I last saw The Beast that summer at the Marine base

in Virginia called Quantico. He rubbed his shaven head,

and the sunburn made the stitches from the car crash years ago

stand out like tiny crosses in the field of his face.

I last saw the Playboy calendar in December of that year,

when it could no longer tell me the week or the month.

I last saw Omar Khayyám this morning:

Awake! He said. For Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight.

Awake! He said. And I awoke.

—

More about Martin Espada: He has published more than fifteen books as a poet, editor, essayist and translator. His latest collection of poems, The Trouble Ball (Norton, 2011), is the recipient of the Milt Kessler Award and an International Latino Book Award. The Republic of Poetry, a collection published by Norton in 2006, received the Paterson Award for Sustained Literary Achievement and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. A previous book of poems, Imagine the Angels of Bread (Norton, 1996), won an American Book Award and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award.

Other books of poems include A Mayan Astronomer in Hell’s Kitchen (Norton, 2000), City of Coughing and Dead Radiators (Norton, 1993), and Rebellion is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands (Curbstone, 1990). He has received numerous awards and fellowships, including the Robert Creeley Award, the National Hispanic Cultural Center Literary Award, the PEN/Revson Fellowship and a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. His work has been widely translated; collections of poems have recently been published in Spain, Puerto Rico and Chile. A former tenant lawyer, Espada is a professor in the Department of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Espada studied history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and earned his JD from Northeastern University. For many years Espada was a tenant lawyer and legal advocate; his first book of poetry, The Immigrant Iceboy’s Bolero (1982), included photographs taken by his father, Frank Espada. Espada’s subsequent books won significant critical attention.

Often concerned with socially, economically, and racially marginalized individuals, Espada’s early work is full of tightly wrought, heart-wrenching narratives. Espada’s book, Rebellion Is the Circle of a Lover’s Hands, won the 1990 PEN/Revson Award and the Paterson Poetry Prize.

Though defiantly and insistently political, Espada’s work is also known for its gentle humor. Leslie Ullman concluded in the Kenyon Review that Espada’s poems “tell their stories and flesh out their characters deftly, without shrillness or rhetoric, and vividly enough to invite the reader into a shared sense of loss.”

Espada won the Paterson Award for Sustained Literary Achievement with the publication of Alabanza; the book was also named an American Library Association Notable Book of the Year. The Republic of Poetry, his next collection, deals with the political power and efficacy of poetry.

Taking cues from documentary poetics as well as formal argumentation and Espada’s ongoing fascination with Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, the volume interrogates the role of poetry in the public and private spheres: poems range from odes to poets like Yusef Komunyakaa and Robert Creeley, to treatments of the Chilean revolution, to anti-war polemics, to ironically sage instruction poems for young poets.

Espada has edited two important anthologies of poetry: El Coro: A Chorus of Latino and Latina Poetry (1997) and Poetry Like Bread: Poets of the Political Imagination (2000). The poets across these two anthologies hail from all over the Americas, bringing an important yet under-represented group of poets to light.

In addition to his work as a translator and editor, Espada has also published two volumes of essays and criticism, Zapata’s Disciple (1998) and The Lover of a Subversive is Also a Subversive (2010). In the Progressive, poet Rafael Campo commended Espada’s courage in Zapata’s Disciple, maintaining that he is one of only a few poets who “take[s] on the life-and-death issues of American society at large.”

The Lover of a Subversive is Also a Subversive considers the role of poetry in political movements. According to poet Barbara Jane Reyes, “To be a poet, Espada asserts throughout this series of essays, is to be an advocate, to advocate for those who have been silenced, and for places that are unspokenOur work as poets can empower the silenced to speak.” Espada himself has never wavered in his commitment to poetry as a source of political and personal power.

In an interview with Bill Moyers, Espada spoke to the impact of poetry on the lives of second-generation immigrants who discover the power of their own experiences through the form: “Poetry will help them to the extent that poetry helps them maintain their dignity, helps them maintain their sense of self respect. They will be better suited to defend themselves in the world. And so I thinkpoetry makes a practical contribution.”

Dennis J. Bernstein is a host of “Flashpoints” on the Pacifica radio network and the author of Special Ed: Voices from a Hidden Classroom. You can access the audio archives at www.flashpoints.net. You can get in touch with the author at dbernstein@igc.org.

Show Comments