Special Report: The 40th anniversary of the Watergate break-in has brought reflections on the scandal’s larger meaning, but Official Washington still misses the connection to perhaps Richard Nixon’s dirtiest trick, the torpedoing of Vietnam peace talks that could have ended the war four years earlier, Robert Parry reports.

By Robert Parry

The origins of the Watergate scandal trace back to President Richard Nixon’s frantic pursuit of a secret file containing evidence that his 1968 election campaign team sabotaged Lyndon Johnson’s peace negotiations on the Vietnam War, a search that led Nixon to create his infamous “plumbers” unit and to order a pre-Watergate break-in at the Brookings Institution.

Indeed, the first transcript in Stanley I. Kutler’s Abuse of Power, a book of Nixon’s recorded White House conversations relating to Watergate, is of an Oval Office conversation on June 17, 1971, in which Nixon orders his subordinates to break into Brookings because he believes the 1968 file might be in a safe at the centrist Washington think tank.

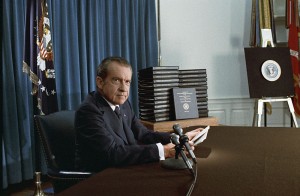

President Richard Nixon, trying to head off impeachment over Watergate, releases edited transcripts of his Oval Office tapes on April 29, 1974. (Photo credit: National Archives)

Unknown to Nixon, however, President Lyndon Johnson had ordered his national security adviser, Walt Rostow, to take the file out of the White House before Nixon was sworn in on Jan. 20, 1969. Rostow labeled it “The ‘X’ Envelope” and kept it until after Johnson’s death in 1973 when Rostow turned it over to the LBJ Library in Austin, Texas, with instructions to keep it secret for decades.

Yet, this connection between Nixon’s 1968 gambit and the Watergate scandal four years later has been largely overlooked by journalists and scholars. They mostly have downplayed evidence of the Nixon campaign’s derailing of the 1968 peace negotiations while glorifying the media’s role in uncovering Nixon’s cover-up of his re-election campaign’s spying on Democrats in 1972.

One of the Washington press corps’ most misguided sayings that “the cover-up is worse than the crime” derived from the failure to understand the full scope of Nixon’s crimes of state.

Similarly, there has been a tendency to shy away from a thorough recounting of a series of Republican scandals, beginning with the peace talk sabotage in 1968 and extending through similar scandals implicating Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush in the 1980 interference of President Jimmy Carter’s hostage negotiations with Iran, drug trafficking by Reagan’s beloved Nicaraguan Contra rebels, and the Iran-Contra Affair and reaching into the era of George W. Bush, including his Florida election theft in 2000, his use of torture in the “war on terror” and his aggressive war (under false pretenses) against Iraq.

In all these cases, Official Washington has chosen to look forward, not backward. The one major exception to that rule was Watergate, which is again drawing major attention around the 40th anniversary of the botched break-in at the Democratic National Committee on June 17, 1972.

Wood-stein Redux

As part of the commemoration, the Washington Post’s star reporters on Watergate Carl Bernstein and Bob Woodward penned a reflection on the scandal, which puts it in a broader context than simply a one-off example of Nixon’s political paranoia.

In their first joint byline in 36 years, Woodward and Bernstein write that the Watergate scandal was much worse than they had understood in the 1970s. They depict Watergate as essentially five intersecting “wars” that Nixon was waging against his perceived enemies and the democratic process, taking on the anti-war movement, the news media, the Democrats, justice and history.

“At its most virulent, Watergate was a brazen and daring assault, led by Nixon himself, against the heart of American democracy: the Constitution, our system of free elections, the rule of law,” they wrote in the Post’s Outlook section on June 10, 2012.

In the article, Woodward and Bernstein take note of the Oval Office discussion on June 17, 1971, regarding Nixon’s eagerness to break into Brookings in search of the elusive file, but they miss its significance referring to it as a file about Johnson’s “handling of the 1968 bombing halt in Vietnam.”

That bombing halt ordered by Johnson on Oct. 31, 1968 was part of a larger initiative to achieve a breakthrough with North Vietnam to end the war, which had already claimed more than 30,000 American lives and countless Vietnamese. To thwart the peace talks, Nixon’s campaign went behind Johnson’s back to convince the South Vietnamese government to boycott those talks and thus deny Democrat Hubert Humphrey a last-minute surge in support, which likely would have cost Nixon the election.

Rostow’s “The ‘X’ Envelope,” which was finally opened in 1994 and is now largely declassified, reveals that Johnson had come to know a great deal about Nixon’s peace-talk sabotage from FBI wiretaps. In addition, tapes of presidential phone conversations, which were released in 2008, show Johnson complaining to key Republicans about the gambit and even confronting Nixon personally.

In other words, the file that Nixon so desperately wanted to find was not primarily about how Johnson handled the 1968 bombing halt but rather how Nixon’s campaign obstructed the peace talks by giving assurances to South Vietnamese leaders that Nixon would get them a better result.

After becoming President, Nixon did extend and expand the conflict, much as South Vietnamese leaders had hoped. Ultimately, however, after more than 20,000 more Americans and possibly a million more Vietnamese had died, Nixon accepted a peace deal in 1972 similar to what Johnson was negotiating in 1968. After U.S. troops finally departed, the South Vietnamese government soon fell to the North and the Vietcong.

‘I Need It’

Yet, in 1971, the file on Nixon’s 1968 gambit represented a real and present danger to his re-election. He considered its recovery an important priority, especially after the leaking of the Pentagon Papers, which revealed the deceptions mostly by Democrats that had led the United States into the Vietnam War.

If the second shoe had dropped revealing Nixon’s role in extending the war to help win an election the outrage across the country would have been hard to predict.

The transcript of the Oval Office conversation on June 17, 1971, suggests Nixon had been searching for the 1968 file for some time and was perturbed by the failure of his staff to find it.

“Do we have it?” Nixon asked his chief of staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman. “”I’ve asked for it. You said you didn’t have it.”

Haldeman responded, “We can’t find it.”

National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger added, “We have nothing here, Mr. President.”

Nixon: “Well, damnit, I asked for that because I need it.”

Kissinger: “But Bob and I have been trying to put the damn thing together.”

Haldeman: “We have a basic history in constructing our own, but there is a file on it.”

Nixon: “Where?”

Haldeman: “[Presidential aide Tom Charles] Huston swears to God that there’s a file on it and it’s at Brookings.”

Nixon: “Bob? Bob? Now do you remember Huston’s plan [for White House-sponsored break-ins as part of domestic counter-intelligence operations]? Implement it.”

Kissinger: “Now Brookings has no right to have classified documents.”

Nixon: “I want it implemented. Goddamnit, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.”

Haldeman: “They may very well have cleaned them by now, but this thing, you need to “

Kissinger: “I wouldn’t be surprised if Brookings had the files.”

Haldeman: “My point is Johnson knows that those files are around. He doesn’t know for sure that we don’t have them around.”

‘The X Envelope’

But Johnson did know that the file was no longer at the White House because he had ordered Walt Rostow to remove the documents in the final days of his own presidency. According to those documents and audiotapes of phone conversations, Johnson left office embittered over the Nixon campaign’s interference, which he privately called “treason,” but he still decided not to disclose what he knew.

In a conference call on Nov. 4, 1968, the day before the election, Johnson considered confirming a story about Nixon’s interference that a Saigon-based reporter had written for the Christian Science Monitor, but Johnson was dissuaded by Rostow, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Defense Secretary Clark Clifford.

“Some elements of the story are so shocking in their nature that I’m wondering whether it would be good for the country to disclose the story and then possibly have a certain individual [Nixon] elected,” Clifford said. “It could cast his whole administration under such doubt that I think it would be inimical to our country’s interests.”

Three years later as Nixon headed toward his re-election campaign, he worried about what evidence Johnson or the Democrats might possess that could be disclosed to the American people. According to Nixon’s taped White House conversations, he remained obsessed with getting the file.

On June 30, 1971, he again berated Haldeman about the need to break into Brookings and “take it [the file] out.” Nixon even suggested using former CIA officer E. Howard Hunt (who later oversaw the two Watergate break-ins in May and June of 1972) to conduct the Brookings break-in.

“You talk to Hunt,” Nixon told Haldeman. “I want the break-in. Hell, they do that. You’re to break into the place, rifle the files, and bring them in. Just go in and take it. Go in around 8:00 or 9:00 o’clock.”

Haldeman: “Make an inspection of the safe.”

Nixon: “That’s right. You go in to inspect the safe. I mean, clean it up.” (For reasons that remain unclear, it appears that the planned Brookings break-in never took place.)

Offense or Defense

In the Outlook piece, Woodward and Bernstein interpret Nixon’s interest in the file as mostly offensive, that his White House team was looking for material that could be used to “blackmail Johnson” in Haldeman’s words presumably over Nixon’s belief that Johnson had engaged in illegal wiretaps of Nixon’s campaign in 1968 regarding its contacts with South Vietnamese officials.

Nixon revived this LBJ-bugged-us-too complaint after the botched Watergate break-in on June 17, 1972. And, Johnson’s silence about the peace-talk sabotage may have convinced Nixon that Johnson was more worried about disclosures of his wiretaps than Nixon was about revelations of his campaign’s Vietnam treachery.

As early as July 1, 1972, Nixon cited the 1968 events as a possible blackmail card to play against Johnson to get his help squelching the expanding Watergate probe.

According to Nixon’s White House tapes, his aide Charles Colson touched off Nixon’s musings by noting that a newspaper column claimed that the Democrats had bugged the telephones of Nixon campaign operative (and right-wing China Lobby figure) Anna Chennault in 1968, when she was serving as Nixon’s intermediary to South Vietnamese officials.

“Oh,” Nixon responded, “in ’68, they bugged our phones too.”

Colson: “And that this was ordered by Johnson.”

Nixon: “That’s right”

Colson: “And done through the FBI. My God, if we ever did anything like that you’d have the ”

Nixon: “Yes. For example, why didn’t we bug [the Democrats’ 1972 presidential nominee George] McGovern, because after all he’s affecting the peace negotiations?”

Colson: “Sure.”

Nixon: “That would be exactly the same thing.”

Over the next several months, the tale of Johnson’s supposed wiretaps of Nixon’s campaign was picked up by the Washington Star, Nixon’s favorite newspaper for planting stories damaging to his opponents.

Washington Star reporters contacted Walt Rostow on Nov. 2, 1972, and, according to a Rostow memo, they asked whether “President Johnson instructed the FBI to investigate action by members of the Nixon camp to slow down the peace negotiations in Paris before the 1968 election. After the election [FBI Director] J. Edgar Hoover informed President Nixon of what he had been instructed to do by President Johnson. President Nixon is alleged to have been outraged.”

Planting a Story

But Hoover apparently had given Nixon a garbled version of what had happened, leading Nixon to believe that the FBI bugging was more extensive than it was. According to Nixon’s White House tapes, he pressed Haldeman on Jan. 8, 1973, to get the story about the 1968 bugging into the Washington Star.

“You don’t really have to have hard evidence, Bob,” Nixon told Haldeman. “You’re not trying to take this to court. All you have to do is to have it out, just put it out as authority, and the press will write the Goddamn story, and the Star will run it now.”

Haldeman, however, insisted on checking the facts. In The Haldeman Diaries, published in 1994, Haldeman included an entry dated Jan. 12, 1973, which contains his book’s only deletion for national security reasons.

“I talked to [former Attorney General John] Mitchell on the phone,” Haldeman wrote, “and he said [FBI official Cartha] DeLoach had told him he was up to date on the thing. A Star reporter was making an inquiry in the last week or so, and LBJ got very hot and called Deke [DeLoach’s nickname], and said to him that if the Nixon people are going to play with this, that he would release [deleted material — national security], saying that our side was asking that certain things be done.

“DeLoach took this as a direct threat from Johnson,” Haldeman wrote. “As he [DeLoach] recalls it, bugging was requested on the [Nixon campaign] planes, but was turned down, and all they did was check the phone calls, and put a tap on the Dragon Lady [Anna Chennault].”

In other words, Nixon’s threat to raise the 1968 bugging was countered by Johnson, who threatened to finally reveal that Nixon’s campaign had sabotaged the Vietnam peace talks. The stakes were suddenly raised. However, events went in a different direction.

On Jan. 22, 1973, ten days after Haldeman’s diary entry and two days after Nixon began his second term, Johnson died of a heart attack. Haldeman also apparently thought better of publicizing Nixon’s 1968 bugging complaint.

Rostow’s Lament

Several months later with Johnson dead and Nixon sinking deeper into the Watergate swamp Rostow, the keeper of “The ‘X’ Envelope,” mused about whether history might have gone in a very different direction if he and other Johnson officials had spoken out about the sabotaging of the Vietnam peace talks in real time.

On May 14, 1973, Rostow typed a three-page “memorandum for the record” summarizing the secret file that Johnson had amassed on the Nixon campaign’s sabotage of Vietnam peace talks to secure the 1968 election victory.

Rostow reflected, too, on what effect LBJ’s public silence may have had on the then-unfolding Watergate scandal. As Rostow composed his memo in spring 1973, Nixon’s Watergate cover-up was unraveling. Just two weeks earlier, Nixon had fired White House counsel John Dean and accepted the resignations of two top aides, H.R. Haldeman and John Ehrlichman.

As he typed, Rostow had a unique perspective on the worsening scandal. He understood the subterranean background to Nixon’s political espionage operations.

“I am inclined to believe the Republican operation in 1968 relates in two ways to the Watergate affair of 1972,” Rostow wrote. He noted, first, that Nixon’s operatives may have judged that their “enterprise with the South Vietnamese” in frustrating Johnson’s last-ditch peace initiative had secured Nixon his narrow margin of victory over Hubert Humphrey in 1968.

“Second, they got away with it,” Rostow wrote. “Despite considerable press commentary after the election, the matter was never investigated fully. Thus, as the same men faced the election in 1972, there was nothing in their previous experience with an operation of doubtful propriety (or, even, legality) to warn them off, and there were memories of how close an election could get and the possible utility of pressing to the limit and beyond.” [To read Rostow’s memo, click here, here and here.]

Also, by May 1973, Rostow had been out of government for more than four years and had no legal standing to possess this classified material. Johnson, who had ordered the file removed from the White House, had died. And, now, a major political crisis was unfolding about which Rostow felt he possessed an important missing link for understanding the history and the context. So what to do?

Rostow apparently struggled with this question for the next month as the Watergate scandal continued to expand. On June 25, 1973, John Dean delivered his blockbuster Senate testimony, claiming that Nixon got involved in the cover-up within days of the June 1972 burglary at the Democratic National Committee. Dean also asserted that Watergate was just part of a years-long program of political espionage directed by Nixon’s White House.

Keeping the Secrets

The very next day, as headlines of Dean’s testimony filled the nation’s newspapers, Rostow reached his conclusion about what to do with “The ‘X’ Envelope.” In longhand, he wrote a “Top Secret” note which read, “To be opened by the Director, Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, not earlier than fifty (50) years from this date June 26, 1973.”

In other words, Rostow intended this missing link of American history to stay missing for another half century. In a typed cover letter to LBJ Library director Harry Middleton, Rostow wrote: “Sealed in the attached envelope is a file President Johnson asked me to hold personally because of its sensitive nature. In case of his death, the material was to be consigned to the LBJ Library under conditions I judged to be appropriate.

“The file concerns the activities of Mrs. [Anna] Chennault and others before and immediately after the election of 1968. At the time President Johnson decided to handle the matter strictly as a question of national security; and in retrospect, he felt that decision was correct.

“After fifty years the Director of the LBJ Library (or whomever may inherit his responsibilities, should the administrative structure of the National Archives change) may, alone, open this file. If he believes the material it contains should not be opened for research [at that time], I would wish him empowered to re-close the file for another fifty years when the procedure outlined above should be repeated.”

Ultimately, however, the LBJ Library didn’t wait that long. After a little more than two decades, on July 22, 1994, the envelope was opened and the archivists began the process of declassifying the contents.

The dozens of declassified documents reveal a dramatic story of hardball politics played at the highest levels of government and with the highest of stakes, not only the outcome of the pivotal 1968 presidential election but the fate of a half million U.S. soldiers then sitting in the Vietnam war zone. [For details, see Consortiumnews.com’s “LBJ’s ‘X’ File on Nixon’s ‘Treason.’”

However, in 1973, Rostow’s decision to keep the file secret had consequences. Though Nixon was forced to resign over the Watergate scandal on Aug. 9, 1974, the failure of the U.S. government and press to explain the full scope of Nixon’s dirty politics left Americans divided over the disgraced President’s legacy and the seriousness of Watergate, whether the cover-up was worse than the crime.

Even today, four decades after Watergate as some of the key surviving players finally conclude that the scandal was much bigger than they understood at the time, the full dimensions of the scandal remain obscured.

Nixon’s interference with Johnson’s peace talks is still not regarded as “legitimate” history despite the now overwhelming evidence. In an otherwise perceptive article, Woodward and Bernstein still don’t appear to understand what happened in 1968 and why Nixon would have been so worried about the missing file and what it might reveal.

Nor has Official Washington come to grips with how Nixon’s destroy-your-enemy politics continues to infuse the Republican Party. After the Watergate scandal, a series of failed investigations let Republican operatives off the hook again and again, from the 1980 “October Surprise” case over Carter’s Iran hostage negotiations (nearly a replay of Nixon’s 1968 gambit) to the various Iran-Contra crimes of the Reagan-Bush years to George W. Bush’s political abuses and national security crimes last decade.

Viewed from a historical perspective, one could conclude that Watergate was an anomaly in that at least some of the perpetrators went to jail and the implicated President was forced to resign. Nevertheless, a top lesson that the Washington press corps drew from Watergate was the gross misunderstanding that “the cover-up is worse than the crime.”

Looking back, Woodward and Bernstein, who built their careers by exposing that cover-up, agree that those pearls of wisdom missed the point that the Watergate cover-up was a minor offense when compared to what Nixon was covering up.

Yet, possibly Nixon’s worst crime obstructing peace talks that could have saved countless lives remains outside Official Washington’s conventional wisdom.

To read more of Robert Parry’s writings, you can now order his last two books, Secrecy & Privilege and Neck Deep, at the discount price of only $16 for both. For details on the special offer, click here.]

Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories in the 1980s for the Associated Press and Newsweek. His latest book, Neck Deep: The Disastrous Presidency of George W. Bush, was written with two of his sons, Sam and Nat, and can be ordered at neckdeepbook.com. His two previous books, Secrecy & Privilege: The Rise of the Bush Dynasty from Watergate to Iraq and Lost History: Contras, Cocaine, the Press & ‘Project Truth’ are also available there.

One might follow up reading this excellent article with one by Woodward and Bernstein in the June 13, 2012, Washington Post at: http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/woodward-and-bernstein-40-years-after-watergate-nixon-was-far-worse-than-we-thought/2012/06/08/gJQAlsi0NV_story.html?hpid=z7

It seems this month is loaded with infamous anniversaries. Jonathan Pollard, the spy who passed more than a million classified documents to Israel, who then passed them on to the Soviet Union, is currently requesting commutation of his sentence with the Obama administration. Apparently, according to a recent Grant Smith article, this issue is a festering boil likely to belch forth its purulent effluvium in conjunction with the ceremony to award Shimon Peres the Medal of Freedom. The Israeli front company, Telogy, caught illegally shipping nuclear weapons components from California to Israel in 2010 apparently also got a pass from our astute justice department. Turning a ‘blind eye’ toward treason does not appear to be a strictly Republican peccadillo, especially when the Israelis are involved. I would strongly recommend reading Smith’s article to anyone delusional enough to believe that our representatives in government are putting America’s interests first. Smith notes, “Israel’s Chief Rabbi Yonah Metzger brashly stated that releasing Pollard would be good for Obama’s reelection campaign.†Clearly blackmail, in my opinion: soliciting the release of a traitor in exchange for campaign support. Treason is treason is treason, whether it’s done on behalf of the Israelis or anyone else. The most poignant stain of Watergate is that we’ve become accustomed to the stench of political whoredom. No matter how false the virtue, how tawdry the brothel or how cheap the perfume with which it is disguised, we cannot see through the hypocrisy. We have lost our self-respect as a nation when we cannot put our own country’s interests above those of a scheming band of crooks and connivers.

Right on!

Comment meant for Mr. Sanford.

Mr Parry, beautifully portrayed article but it’s time to bury that hatchet. The greater, domineering, smothering force, ever self-evolving has arrived. It’s the next step (up?) in evolution and it looms limitless… nano computing and that “singularity” outlined by Ray Kurzweil. We let our machines get ahead of us…I still get a warm feeling, fondly recalling those heavy and bulky KYX secure telephones and large tape recording devises used by Nixon and his plumbers. The technology was more manageable then and easy to spot! One would work up a sweat moving it about, plugging it in, stuffing it behind some panel. But now we seem unable to legislate or in any way mitigate on behalf of privacy and freedom, which are in Great Peril! No known government entities or other recognized institutions can save us from the consequences of this micro miniaturization. I wonder what ‘ol tricky Dick would suggest we do now, if only he could speak from the netherworld?

Elmer? What makes you think he hasn’t been speaking (and cackling gleefully) from the under, er, I mean the other side?

In essence, since 1968 the Republican Party has contained a criminal element willing to lie, cheat, steal and betray their country to win elections. With Nixon it was small, evidenced by the fact that it was other Republicans who told him he had to resign, but it has grown to the point where more or less the whole party is a treasonous criminal enterprise. The latest example is the refusal of the Republicans to do anything to help the American people because anything they do may benefit President Obama