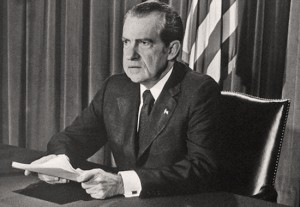

Four decades ago, Richard Nixon resigned, making him the first U.S. president in history to quit the office, the result of two years of a spreading scandal known as Watergate. But many Watergate reforms aimed at limiting the power of money over politics were short-lived, as Michael Winship observes.

By Michael Winship

In August 1974, forty years ago this week, commentator Alistair Cooke faced a dilemma. The events of the Watergate scandal “a Laurel and Hardy absurdity in the beginning,” Cooke recalled had snowballed since 1972 from a farce of botched burglary into a severe constitutional crisis, and events were building to a big finish.

A few days before, the House Judiciary Committee had voted for three articles of impeachment against Richard Nixon. It seemed clear that the full House would support the committee and impeach the president, and that the Senate would convict.

What was Nixon going to do defy Congress? Resign? “He’ll brazen it out,” the historian Samuel Eliot Morison told Cooke. There even were rumors of a coup d’état. Washington hadn’t been so enflamed and jittery since the Civil War, when Confederate troops were camped just across the Potomac or when the British put the city to the actual torch during the War of 1812.

In those early August days, events would reach a crescendo but none of us knew the final outcome, and that was Alistair Cooke’s problem. Each week, the learned, avuncular author and BBC correspondent (best-known to U.S. public TV watchers as the host of “Masterpiece Theatre”) recorded a “Letter from America” for BBC radio worldwide. But to have it ready for the weekend, he always recorded it on Wednesday so this time, his deadline meant he would have to deliver his letter before anyone knew for sure what Nixon’s fate would be.

So what was Cooke going to do? He decided to relate to his audience everything that had happened so far: the articles of impeachment, the impending House vote and Senate trial, and the Aug. 5 release to the public of the so-called “smoking gun” tape, a recording of the June 23, 1972, meeting at which Nixon said the FBI should be told to shut down its investigation of the Watergate break-in. Cooke listed Nixon’s options. And then, he said this: “The rest you know.”

It was the perfect solution. Masterly, fans wrote Cooke. So dramatic, so tasteful, they said, wonderful restraint. None of them knew that chronological necessity had been the mother of rhetorical invention, that the commentator had plucked a plum from the prickles of chaos and uncertainty.

There was a lot of scrambling that week. I was working in Washington at my first television job, in the employ of NPACT, the National Public Affairs Center for Television. We supplied public television with its Washington coverage: everything from monthly documentaries and live coverage of congressional hearings, to three weekly series, including Washington Week in Review.

The previous year, NPACT had produced gavel-to-gavel coverage of the Senate Watergate Committee hearings, the first pairing of Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer. The primetime repeats of those hearings helped establish PBS as a player and raised millions in pledge money a wonderful irony in the face of Nixon’s attempts to bludgeon public television to death.

Nominally, I was in charge of publicity and advertising, but we were small in number and in a crisis, doubled and tripled at different jobs. That summer, we had co-produced with the BBC and CBC a dramatic recreation of President Andrew Johnson’s impeachment trial in 1868 (I remember reading All the President’s Men, hot off the press, on the flights to and from Raleigh, North Carolina, where we videotaped). We had just finished our daily coverage of the House Judiciary Committee hearings and I had been the editorial assistant, pulling wire copy, making phone calls, helping however possible.

Suddenly, everything came together in a rush. Monday, Aug. 5, we were making calls to contacts on Capitol Hill, trying to figure out how a trial would work. Later that day, with the release of the smoking gun tape, Nixon said, “I am firmly convinced that the record, in its entirety, does not justify the extreme step of impeachment and removal of a president.”

Tuesday and Wednesday, emergency meetings with Republican leadership were held at the White House, with even the most diehard supporters on the judiciary committee finally telling Nixon he had to go. Whatever was going to happen, NPACT made contingency plans for a four-and-a-half hour special that would take up the entire PBS evening schedule.

Thursday, Aug. 8, we knew Nixon would speak to the nation that night. I went to Lafayette Park to tape promos with our White House correspondent. Crowds already were beginning to gather. At 9 p.m., we were in the studio, listening to Nixon’s resignation address.

Except for his voice it was silent and I thought of what one observer had said more than a century before, during the Senate vote on whether or not to convict Andrew Johnson: “Such a stillness prevailed that the breathing of the galleries could be heard.”

I got home but it seemed anticlimactic, so I called a girlfriend who had a car and convinced her to drive with me back to Lafayette Park where the celebration was in full swing. For weeks, demonstrators had stood along Pennsylvania Avenue with signs: “Honk if you think he’s guilty.” Motorists had responded enthusiastically, and now the sound of their horns and accompanying cheers was like Times Square on New Year’s Eve at midnight.

Friday morning, Aug. 9, I got to the office just as Richard Nixon was making his second speech, the slightly bizarre and emotional East Room address to his cabinet and staff in which he invoked his father’s lemon ranch, his mother’s saintliness, passing the bar exam and White House décor. Then he and his family boarded the helicopter to Andrews Air Force Base and minutes after, Gerald Ford was sworn in as the new president.

That night, our mega-special aired, titled “America in Transition.” It wasn’t a summing up of Nixon and the two previous years; instead, it tried to look at what was ahead. I was in charge of two segments dealing with overseas press reaction and foreign policy.

It was the first show on which I’d ever worked that had an open bar in the green room. Loquaciousness and hilarity ensued. I remember the late, great Pete Lisagor, Washington bureau chief of the Chicago Daily News, announcing on the air that Ronald Reagan didn’t dye his hair, it was prematurely orange.

“Our Constitution works,” President Ford had said earlier that day. “Our great Republic is a government of laws and not of men. Here the people rule.”

For a brief time, better things seemed possible and some actually happened: the bridling of an imperial presidency, the movement for campaign finance reform, a raising of ethical standards, greater oversight of the FBI and CIA because, as historian Garry Wills told Newsweek in 1982, ten years after the Watergate burglary, “We had turned to spying on ourselves; Presidents were setting up teams to topple foreign governments.” Goodness, who could imagine such things today?

The changes didn’t last. The rest you know.

Michael Winship is the Emmy Award-winning senior writer of Moyers & Company and BillMoyers.com, and a senior writing fellow at the policy and advocacy group Demos.

Show Comments