Exclusive: President Lyndon Johnson’s legacy is in the news whether his many domestic achievements should outweigh his disastrous escalation of the Vietnam War but no attention is being paid to evidence that LBJ might have ended the war if not for Richard Nixon’s sabotage, writes Robert Parry.

By Robert Parry

Many important officials and journalists have spent time at the LBJ Library in Austin, Texas, this past week celebrating the half-century anniversary of one of President Lyndon Johnson’s signature achievements, the Civil Rights Act. But no one, it seems, took time to look at what the library’s archivists call their “X-File,” documents that could change how history views Johnson’s legacy.

The “X-File” is the nickname that the archivists gave to Johnson’s secret file on what he considered Richard Nixon’s “treason” in sabotaging Vietnam War peace talks to gain an edge over Hubert Humphrey in the close 1968 election. The “X-File” is actually “The X envelope,” the words scribbled on the outside by Johnson’s national security adviser Walt Rostow.

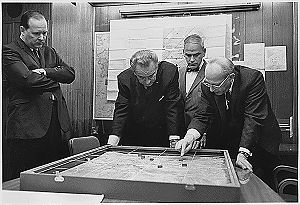

National Security Adviser Walt Rostow shows President Lyndon Johnson a model of a battle near Khe Sanh in Vietnam. (U.S. Archive Photo)

As a bitter Johnson was leaving the White House in January 1969, he ordered Rostow to take the top-secret file which included national security wiretaps of Nixon’s representatives urging South Vietnamese officials to boycott Johnson’s Paris peace talks and offering a better deal if Nixon won.

Johnson had hoped he could bring the war to a close before his presidency ended, but in late October 1968, South Vietnamese President Nguyen van Thieu balked at the peace talks as the Nixon team had requested. The failed negotiations gave a last-minute lift to Nixon who eked out a narrow victory over Humphrey.

Johnson chose to keep silent about what Nixon’s had done but wanted to keep the file out of Nixon’s hands. So LBJ entrusted it to Rostow who simply took the file home with him and kept it, as instructed, until after Johnson’s death on Jan. 22, 1973. For several months, Rostow struggled over what to do with the file before finally entrusting it to the LBJ Library with instructions to keep it secret for 50 years.

However, in 1994, library officials decided to open the file and began the work of declassifying the documents, a few of which remain classified to this day. I was given access to the file in 2012 and published a lengthy story at Consortiumnews.com. I also included the information in my latest book, America’s Stolen Narrative. After my reporting, the BBC published an account in 2013 recognizing the significance of the new evidence.

“The X-envelope” also played a role in two other controversies of the Nixon years: the Pentagon Papers and Watergate, offering insights into how the two events were tied together. The narrative goes this way:

After taking office in 1969, Nixon learned about LBJ’s wiretap file from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, but Nixon’s top aides, Henry Kissinger and H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, could not locate it. They had no idea that Rostow had taken the file home with him when he left the White House at the end of LBJ’s presidency.

Nixon’s concerns about the missing file became more urgent in June 1971 when the New York Times began publishing the Pentagon Papers, a secret history of the Vietnam War that had been leaked by former Pentagon official Daniel Ellsberg. The Pentagon Papers chronicled many of the deceptions that had led the United States into the bloody Vietnam conflict, but the historical chronology stopped in 1967.

As the Pentagon Papers dominated the U.S. news in mid-June 1971, Nixon understood something that few others did that there was a sequel somewhere that could have been even more explosive than the Pentagon Papers, the story of how Nixon’s 1968 presidential campaign had conspired with South Vietnamese officials to extend the war.

If Rostow’s “X envelope” had surfaced then, Nixon’s reelection would not only have been put in jeopardy but he might well have faced impeachment. Just a month earlier, the May Day protests had brought hundreds of thousands of anti-war activists to Washington, government buildings had been surrounded, and thousands of people were arrested. It is hard to even imagine the fury that would have followed disclosure that Nixon had torpedoed peace talks for political gain.

With the May Day protests fresh in his mind and confronting the media frenzy over the Pentagon Papers, Nixon ordered Kissinger and Haldeman to resume their search for the missing file. In a tape-recorded conversation on June 17, 1971, Nixon even instructed his people to break into the Brookings Institution where he thought the file might be.

On June 30, 1971, Nixon returned to the topic, suggesting that ex-CIA officer E. Howard Hunt be brought in to put together a team to handle the job. “You talk to Hunt,” Nixon told Haldeman. “I want the break-in. Hell, they do that. You’re to break into the place, rifle the files, and bring them in. Just go in and take it. Go in around 8:00 or 9:00 o’clock.”

Haldeman: “Make an inspection of the safe.”

Nixon: “That’s right. You go in to inspect the safe. I mean, clean it up.”

For reasons that remain unclear, it appears that the planned Brookings break-in never took place, but Hunt did put together a team of burglars who conducted other operations, including breaking into the Democratic National Headquarters at the Watergate building where part of the team was captured on June 17, 1972. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “The Dark Continuum of Watergate.”]

Though Rostow’s “X envelope” contains information that could dramatically reshape history’s understanding of both the Johnson and Nixon presidencies, it continues to attract very little attention even when groups of very important people visit the LBJ Library seeking to put President Johnson’s legacy in clearer focus.

Despite the visit by President Barack Obama and the traveling press corps on Thursday, Rostow’s documents still remain as mysterious as the spooky “X-Files” series that the archivists were referencing when they dubbed the papers their “X-File.” On Friday, when I ran a Google news search for “Johnson, Nixon, Rostow, Vietnam War,” nothing came up.

Investigative reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his new book, America’s Stolen Narrative, either in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com). For a limited time, you also can order Robert Parry’s trilogy on the Bush Family and its connections to various right-wing operatives for only $34. The trilogy includes America’s Stolen Narrative. For details on this offer, click here.

…” disastrous escalation of the Vietnam War.” I really have a problem with this mild terminology. It is as if the problem was that the war didn’t turn out so well. LBJ was a total psychopath; if you doubt that research the USS Liberty false flag operation. In that incident a US Navy recon ship well off of Israel during the six day war was attacked with bombs, napalm and strafing by Israeli forces with the intent to blame it on the Egyptians. LBJ was totally in collusion and refused to allow carrier planes to defend the ship. The ship did not sink according to plan and the survivors are glad to tell the story. https://www.usslibertyveterans.org/‎. This was probably the most revoltingly treacherous behavior by a US president in history.

Better terms might be, monstrous, vicious, criminal, as his prosecution of the war was all of that. He deserved the fate of the high ranking Germans who were tried at Nuremberg he is no better than they. He had a fanatical hate for Ho Chi Minh which colored his reason and made for a tactical obsession to the detriment of the Vietnamese people and American soldiers.

The fact that he refused to expose Nixon, which would have turned the latter instantly and forever into a smoldering political corpse, demonstrates his total lack of morals. In contrast it shows a loyalty to the concept of a political elite who stand above, in a bi partisan manner, the American people. In other words it is the establishment both Democrat and Republican that counts not honesty or decency or the rule of law. So even when the opposite side commits a heinous crime it must be hidden to preserve the public’s dwindling confidence in the system. His own words in the tapes admit the latter point.

As far as his civil rights legislation is concerned, it is a testimony to his political clout not any sense or right or wrong. Just like billionaires and millionaires who spend their lives squeezing profits out of their workers and public and then give away millions to philanthropy (tax deductible); it makes him look good, a legacy to be known by. This is well shown by the first sentence in the article, so people can think gee he did good, but to bad he got messed up in that ill begotten war.

And frankly I doubt LBJ would have been willing to compromise enough to end the war in ’68 even without Tricky Dick’s interference. He was one stubborn piece of work with an ego as big as his home state.

The reason LBJ did nothing to Nixon is because Nixon had the goods on LBJ. Nixon knew what LBJ had done…I will let you figure out what secret that was.

MLK died on LBJ’s watch…nothing to see here, now move along!

LBJ had a LOT more to account for than this article relates —

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=POmdd6HQsus

http://www.thecanadiandaily.ca/man-killed-kennedy-case-lbj/

Surely this couldn’t happen in America. But it did. And it happened again with Reagan’s traitorous acts regarding the Iran hostages.

It is shameful that most of us cover our ears and eyes to such treasonous acts. The irony is we do it out of a sense of patriotism…crazy

If we truly loved our Country and its citizens we need to expose these crimes, hold the perpetrators accountable and “the hard part” be ashamed for what our leaders have done in our name. Whether they be Republican or Democrat should not be another reason to ignore or bury them.

In Nixon’s crime many thousands of Americans and exponentially more Vietnamese DIED because of his interference with the peace talks.

In Reagan’s case, we know at least the American hostages and their families suffered great mental anguish as did President Carter.

I often wondered if we had done the right thing and exposed the truth to the American people if Bush/Cheney would have thought a lot harder before they lied and mislead us into the Iraq war travesty.

Politicians, banks, fossil fuel corps, automakers, drug manufacturers NEED to know that they WILL be accountable and pay the price when they make bad/illegal decisions. How many examples do we need before we realize this? and why are only the rich and powerful exempt from the laws of this country?