Lebanese journalist Talal Salman was renowned in his region, but less known in the West. He was one of the most influential journalists in the Middle East, coming from a pre-Gulf dominated era of Arab journalism.

Talal Salman, undated. (Assafir newspaper, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Lebanon has just bid farewell to the famous Arab journalist Talal Salman, marking the end of an era in Arab journalism.

Lebanon has just bid farewell to the famous Arab journalist Talal Salman, marking the end of an era in Arab journalism.

Salman did not have drinks regularly with New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman when he visited the region, nor did he share anecdotes with Washington Post associate editor and columnist, David Ignatius. But he was one of the most influential journalists in the region, with a career spanning over six decades.

He died on Aug. 26 aged 85. Salman was born into a poor family in Lebanon. His father was a police guard in Shmastar, Baalbak. He started a career in journalism early in life and worked his way up to senior positions in a variety of publications.

He made his mark mostly in Al-Hawadith and As-Sayyad, leading political magazines that expressed Arab nationalist perspectives, before being co-opted by Gulf regimes after the death of Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser in 1970. Salman also worked at Al-Huriyyah, the magazine of the Movement of Arab Nationalists.

Steadfast Supporter of Nasser, Palestinian Cause

In a region where journalists switch allegiances depending on funding received, Salman stuck to his Nasserist Arab nationalist orientation and never wavered in his support for Palestinians. He referred to the ultimate prize of liberating Palestine as the “Eid,” akin to a religious holiday.

He did later benefit from the largesse of the Libyan regime and from businessman and Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri.

Salman is not widely known in the West because he did not provide sound bites to Western journalists and did not speak the languages of Western media. He wrote in beautiful classical Arabic and was happy to express himself to Arab audiences.

In the Arab world, he was widely known as the steadfast supporter of Nasser and Palestinian liberation. He made his name from writing for As-Sayyad when it was a leading weekly political magazine. (All Arab political magazines are now defunct, with the exception of the Saudi propaganda weekly, Al-Majallah.) He specialized in writing about the Palestinian resistance movement when its rise captured the imagination of Arabs around the world.

Unfortunately, in hindsight, those hopes, placed in the PLO leadership, were largely misplaced. The Yasser Arafat leadership would take the movement along a disastrous path leading to the Oslo agreements, which produced the corrupt and subservient Palestinian Authority. In the early 1970s, Salman traveled to Jordan and interviewed key Palestinian leaders and commanders and wrote a series of articles to introduce them to Arab readers. The articles were later collected in his book, With Faith, and the Fida’iyyin.

Founded Pan-Arab As-Safir

At an Arab summit in Libya in 1969, shortly after the September Revolution that toppled King Idris I and brought Colonel Mu’ammar Al-Qadhafi to power. The new Libyan leader Qadhafi sits in military uniform in the middle, surrounded by Nasser, left, and Syrian President Nur al-Din al-Atasi, right.

(The Online Museum of Syrian History, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

During his work at As-Sayyad, Salman met Mu’ammar Al-Qadhafi. The former had grandiose dreams of inheriting the mantle of Nasser and wanted to spread his message in the Arab world. Qadhafi saw himself as bigger than Nasser. He wanted to be taken seriously, not only as a pan-Arab leader but also as a thinker.

Toward that end, he wrote his Green Book which he envisioned as an alternative theory to both capitalism and Marxism. It was actually nothing more than general observations with socialistic streaks. His former foreign minister, Abdul-Rahman Shulqum, recently stated in his memoirs that Qadhafi had actually written the book himself, not a great feat, given the outcome.

Qadhafi funded many Palestinian organizations and Arabic publications, but none advanced his cause more than As-Safir, which Salman founded using Libyan funding.

As-Safir (The Messenger) was launched in 1974 and it quickly made a name for itself, not only as the second Lebanese newspaper — after the right-wing An-Nahar (which enjoyed Gulf and Western funding) — but also as an influential pan-Arab newspaper, carrying the message of Nasser and Palestine throughout the region. It was genuinely the first pan-Arab newspaper, as it covered all corners of the Arab world.

Salman enjoyed generous funding and hired correspondents in the Arab world and in key Western capitals. He was a hands-on publisher. His most famous editor-in-chief, the late Joseph Samahah, who would later co-found Al-Akhbar, told me Salman couldn’t help intervening editorially. Salman enjoyed the process of putting out a newspaper too much. He would write the leading opening article and even the headlines. Readers still remember his most famous headlines during the civil war.

But he was an excellent manager of a newspaper. He knew how to hire talent and how to train them. And he brought in writers from all over the Arab world, especially from Egypt where Nasserist writers found an outlet when Anwar Sadat was combating the last vestiges of Nasserism.

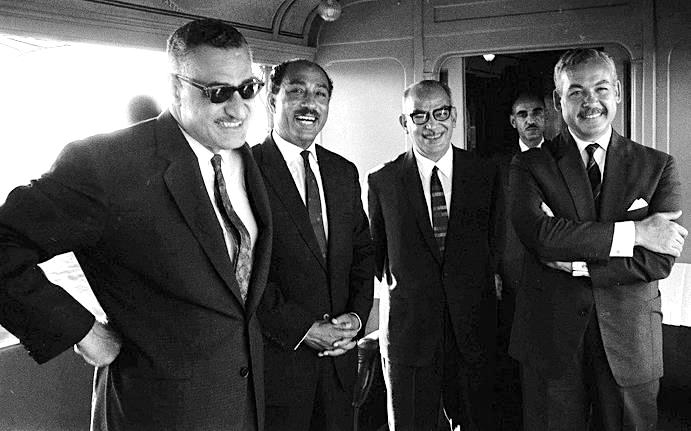

Top Egyptian leaders of the Arab Socialist Union in Alexandria in 1968. From left, Nasser, Sadat, ASU head Ali Sabri and Vice President Hussein el-Shafei. (Bibliotheca Alexandrina and Gamal Abdel Nasser Foundation, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Many of the Lebanese writers in Gulf regimes’ media started their careers at As-Safir and most of them transformed from progressive Arab nationalists and communists to outright right-wing reactionaries. Hazim Saghieh, who is a well-known loyal Lebanese columnist in Saudi media, called for the murder of Sadat when he visited Jerusalem in 1977. He wrote that opinion piece in As-Safir. Now Saghieh favors peace with Israel and mocks what he calls “rejectionists.”

The paper had to respect the agenda of its funder, Qadhafi. Salman would travel to Libya regularly and would publish long tedious interviews with the Libyan ruler. He would even publish “intellectual” interviews in which Qadhafi would be allowed to elaborate on his themes from the Green Book and on his so-called original political system of Jamahiryyah (state of the masses).

Thorn in Side of Conservative Regimes

The paper raised the ire of Gulf governments and would publish articles by Gulf dissidents. It quickly emerged as a thorn in the side of conservative Arab regimes. Many of the Arab world’s leading dissidents were hosted at As-Safir.

But over time the paper became less radical and more mainstream. Qadhafi’s funding dwindled and then disappeared. Salman, born a Shiite, found it awkward to accept Libyan funding after the disappearance of Imam Musa As-Sadr, who Qadhafi allegedly kidnapped and subsequently killed, although his body was never found.

In the 1990s, the paper started receiving funding from Lebanon’s late prime minister, Rafiq Hariri, who fully or partially funded almost all newspapers and magazines in the country. Former Prime minister Salim Huss told me in 2000 that every single publication in Beirut at the time was receiving funding from Hariri.

April 16, 2002: U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, left, escorts Hariri into the Pentagon for a meeting. (DoD, R. D. Ward, Wikimedia Commons)

Hariri not only insisted on favorable coverage of himself and his role, but he also intervened to prohibit criticism or attacks of the Saudi regime, his main political benefactor. Salman struggled during those years. He was a progressive at heart, but he relied on Hariri funding to continue his venture.

[Related: THE ANGRY ARAB: The Origins of Lebanon’s Protests]

Advertisement revenues declined and the challenge of publishing a newspaper became far more difficult in the age of the internet. He tried to appeal to a younger generation by publishing a youth supplement in which he recruited new talent and paid great attention to cultural and literary matters.

A fine writer of Arabic prose himself, he would feature political writing on the front page and writing about love and flirtation in the inside section of the paper. He paid heavily for his political courage. In 1994 he was sprayed with bullets, allegedly by the Lebanese government of Amin Gemayyel, who was trying to sign a peace treaty with Israel, to the stern disapproval of Salman.

As-Safir folded in 2017, which left a great vacuum. I continued to expect to read As-Safir weeks after it closed down. Salman would continue to write articles on his site but it was not the same — not for him and not for his readers. His love for Arab nationalism and for Palestine liberation stayed true until he died. Arabs of different generations are mourning him.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004) and ran the popular The Angry Arab blog. He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

We are sorry for you deep loss. He sounded like a principled and very talented man.

Thank you for sharing what you knew about this gentleman.

Sad news, the world needs his kind of journalism and his kind of courage.

A touching and honest tribute to a man I had never heard of until now. It is clear that I am much the poorer for not having known him and his prose. May he rest in peace.

agreed. I too have never heard of him.