The movie “Lincoln” was a dramatic depiction of the political fight to end American slavery with the 13th Amendment and presented a rare sympathetic portrayal of anti-slavery Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, played by Tommy Lee Jones. This offered a belated chance to reconsider this courageous fighter for freedom, says William Loren Katz.

By William Loren Katz

I’m rooting for Tommy Lee Jones to win an Oscar for his riveting performance as Congressman Thaddeus Stevens in Lincoln. Full disclosure: as an historian my hope is this might focus important attention on Stevens. This flamboyant congressman, his radical vision and his lashing tongue had gained enormous name recognition in his time, but it was not the kind a mother would want for her famous son.

Until the modern civil rights movement those who wrote U.S. history took a heavy stick to Stevens. He wouldn’t have cared. By the time he died in 1868 he had earned the appreciation of millions he helped free from slavery, and further admiration as “the father of the 13th, 14th and 15thAmendments.” But until Tommy Lee Jones donned the man’s grim look, sharp wit, bulky swagger and advanced racial views, Stevens faced a thrashing in classrooms, textbooks and movies.

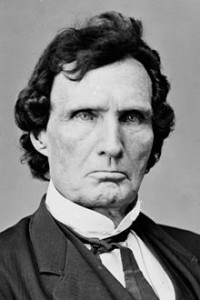

Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, an anti-slavery Republican from Pennsylvania. (Library of Congress, Public Domain Wikimedia Commons)

In 1915, Hollywood’s first blockbuster, Birth of A Nation, offered a systematic character assassination of “Congressman Austin Stoneman.” Neither before nor since has the media so venomously portrayed a U.S. elected official, and this was half a century after Stevens died.

The film has Stevens ruining the South by elevating ignorant former slaves to high office. This in turn, the script continues, encourages African-American officials [played by white actors in black face], to rape white women. In the final scenes the Ku Klux Klan rides in to save white womanhood and Christian civilization. This served an additional purpose. Once again the white public does not learn that the South’s rapists during and after slavery were planters who held whips and guns as well as public office.

To make its tale believable Birth of A Nation was given a documentary look, a stamp of historical truth and the endorsement of President Woodrow Wilson who called it “history written in lightening.” For decades millions of men, women and children learned to hate Black people and cheer the Klan. The huge KKK of the 1920s 4,000,000 members — began shortly after the movie’s debut in Atlanta, Georgia. It even took a nationwide NAACP protest to remove a scene showing Klansmen castrating a Black man.

Stevens fared marginally better in Tennessee Johnson where the famous Lionel Barrymore portrayed a malicious, politician plotting to destroy the South and white supremacy. Then a heroic President Andrew Johnson [Van Heflin] restores “home rule.”

Between the 1915 silent epic and the 1942 feature most scholars climbed on the same bandwagon. Echoing his profession’s view, Pulitzer Prize historian James Truslow Adams called Stevens “perhaps the most despicable, malevolent, and morally deformed character who has risen to high power in America.”

It is true that Thaddeus Stevens unleashed nasty invective on slaveholders, ridiculed incompetents, and steadily elbowed a cautious Lincoln toward emancipation. However, in 1861 the new President was far from “The Great Emancipator.” Lincoln’s First Inaugural stated he would sign an Amendment [the original “13th”] that would make slavery permanent. For his first 17 months in office he refused to propose emancipation, and ordered his commanders in the field to return all runaways to their owners.

As the war continued to roll up casualties with few victories for the Union, he announced his plan to issue a formal declaration on Jan. 1, 1863, and only as a war measure. But a month before in his annual address to Congress on Dec. 1, 1862, Lincoln endorsed a plan for gradual and compensated emancipation. Given the President’s slow, wavering record, abolitionists and people of color had every reason to worry about a slip between the cup and the lip.

Stevens pursued a different path and faster pace: “There can be no fanatics in defense of genuine liberty.” He did not shrink from hazardous combat against the Fugitive Slave Law. His law office in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, was an Underground Railroad station.

When a band of armed slave runaways in nearby Christiana opened fire on a slaveholder posse led by a U.S. Marshall, Pennsylvania’s most famous attorney defiantly volunteered for their defense and won acquittal for the arrested.

Even Stevens’s fiery attacks on slaveholders came with some risk. Twice on the House floor he had to fend off Bowie knife-wielding Southern colleagues. His ally, abolitionist Sen. Charles Sumner, was not so lucky. As he sat at his desk Sumner was beaten senseless by South Carolina Congressman Preston Brooks swinging a heavy cane. Sumner never completely recovered and Brooks won wide praise from slaveholders.

Stevens’s History

From his birth in 1792 in Vermont, Thaddeus Stevens lived with adversity. His father Joshua was an alcoholic shoemaker unable to hold a job so the family struggled. Then when Joshua disappeared never to return, his mother Sally had to pick up the pieces. Resourceful, energetic and determined to see her four boys educated, she paid family bills through long, grueling work as a maid and housekeeper.

Thaddeus also stepped into life with a clubfoot when society saw this as a Devil’s curse, a sign of mental depravity. From an early age, he learned how to duel with people who derided him, think for himself and stick to his guns. His own fight against irrational hate may have opened his heart to others society classified as lesser humans.

Stevens graduated with a law degree from Dartmouth College and opened a law office in Pennsylvania. His fortunes changed when he bought an iron works and a forge, and invested in farmland. He was elected to the state senate just as the legislature voted down an education bill because it raised taxes to aid poor families.

Stevens stormed into the fight with this argument: “The blessing of education shall be conferred on every son of Pennsylvania, shall be carried home to the poorest child of the poorest inhabitant of the meanest hut of your mountains, so that even he may be prepared to act well his part in this land of freedom, and lay on earth a broad and solid foundation for that enduring knowledge which goes on increasing through increasing eternity.”

His speech led to passage of the state’s education law and made him “the father of public education in Pennsylvania.”

In 1848, Stevens was elected to Congress raring to fight the “slaveocracy.” He was also drawn to issues of economic injustice. In 1852, he opposed employers who sought to “get cheap labor” by lowering American workers’ wages to European levels, and by using under-paid women laborers. Such efforts, he insisted, keep “the laboring classes [with] scarcely enough to feed and clothe them . . . [and] nothing to bestow on the education of their children.”

In 1853, Stevens had to return to his law office to pay business debts of over a quarter million dollars. But in 1859, he returned as a Republican Congressman. When it was far from popular he denounced bigotry, spoke in defense of Native Americans, Jews, Mormons, Chinese and women’s rights. And he intensified his crusade against the slaveholder aristocracy.

Stevens had never married and since 1848 shared his large Lancaster home with Lydia Hamilton Smith, an African-American, and her two sons from a previous marriage. While he and Mrs. Smith considered their relationship a common law marriage, his foes saw coarse degeneracy. He refused to publicly explain what he considered a private matter.

His will left Mrs. Smith enough money to purchase the family home and live in comfort. In Birth of A Nation, Mrs. Smith, played by a pudgy white actor, greets news of Lincoln’s assassination with a dance and shout: “You are now the most powerful in the United States.”

Despite his differences with the President, Stevens forged a respectful alliance with the politician he came to call “the purest man in America.” As chairman of the Ways and Means Committee, his control of the war’s finances made him the most powerful member of the House. Lincoln held the power to make emancipation permanent. The two needed each other.

In the movie Lincoln, Stevens is cast as the radical whom Lincoln must tame to insure passage of the 13th Amendment. This is Hollywood drama. The ardent abolitionist was as shrewd a politician as Lincoln and needed no persuasion to support his life’s goal.

Fawn Brodie, Stevens’s admiring biographer, calls him “the scourge of the South.” But Stevens’s harsh, lacerating tongue speared congressional incompetents as well as pro-slavery Southerners and Northerners. He could reduce political foes to gibbering self-doubt.

During the pivotal Gettysburg campaign in 1863, a Confederate Army rode out to kill him. Confederate Major General Jubal Early detoured his Army of Northern Virginia from Gettysburg to Stevens’s iron works at today’s Caledonia State Park. Unable to find him, “hang him on the spot and divide his bones,” Early ordered his men to burn everything and steal his horses, mules, grain and iron bars. Stevens had to borrow money to rebuild.

Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation brought the two men together. Stevens called it “a page in the history of the world whose brightness shall eclipse all the records of heroes and of sages.” Now “this Republic [could] become immortal.” The two now marched down the same road, Stevens, as always, at a quicker pace.

As the war’s casualties passed half a million and its cost soared to $4 billion, Stevens’s concern turned to those who bore the greatest burdens — “the poor widow, the suffering soldier, the wounded martyr to his country’s good.” He denounced the new draft law that allowed a rich man to hire a substitute for $300 and which led to four days of rioting among the poor in New York City.

As real wages fell and business profits rose, he denounced bankers [whom he never liked] and “war profiteers.” In vain he and his committee tried to prevent Northern manufacturers from selling the government useless rifles and damaged goods at inflated prices. He wished “no injury to any, but if any must lose, let it not be the soldier, the mechanic, the laborer and the farmer.”

Stevens explored new directions. He welcomed the liberation of Russia’s serfs as a step toward world freedom. He encouraged a women’s delegation to hasten their drive for the suffrage. When Napoleon III of France made Emperor Maximilian his puppet ruler of Mexico, Stevens urged Congress to aid and provide loans to Mexico’s Indian President Benito Juarez.

As he grew older, friends called Stevens “The Great Commoner.” He asked to be remembered as one who tried “to ameliorate the condition of the poor, the lowly, the downtrodden of every race and language and color.”

He said, “I have done what I deemed best for humanity. It is easy to protect the interests of the rich and powerful. But it is a great labor to protect the interests of the poor and downtrodden.” His enemies said he betrayed his country and his race, and often his class.

For Stevens and the United States, everything changed when the assassination of President Lincoln brought Andrew Johnson to the White House. A poor white scornful of African-Americans, he envied and worked to restore the power of the South’s planter class.

Stevens plan for “a radical reorganization in Southern institutions, habits and manners” led to repeated clashes. Stevens also faced a Republican Party increasingly dominated by Northern business interests who valued trade relations with former slaveholders, not the new Constitutional amendments abolishing slavery and requiring equal protection under the law.

Stevens failed to bring justice, equality and a fair distribution of land and power to the South. But Stevens knew his and other abolitionist prodding led Lincoln toward emancipation and then to voicing support for voting rights for Black soldiers and educated Black males. Lincoln said as much: “I have only been an instrument. The logic and moral power of Garrison and the anti-slavery people of the country and the army, have done all.”

Yes, Stevens can be faulted for his truculent manner, for believing he could defeat his foes’ economic and political influence, and for seriously underestimating racism’s grip nationwide. He fought to have the black and white poor own land, attend school, vote and enjoy equal rights. Though this proved to be an unfulfilled dream, he could not be faulted for his effort. It would require another century, other, younger dreamers both African-American and white.

In death Stevens affirmed his goals. His coffin was carried to the Capitol by an honor guard of five African-American and three white soldiers. He had asked to be buried in the one Lancaster cemetery open to all races.

His grave stone bore his own epitaph: ”I repose in this quiet and secluded spot not from any natural preference for solitude, but finding other cemeteries limited as to race by charter rules, I chosen this that I might illustrate in my death the principles which I advocated through a long life: equality of man before his Creator.”

Yes, Tommy Lee Jones deserves an Academy Award, and Thaddeus Stevens deserves a full hearing!

William Loren Katz is the author of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage, and forty other books on African American history. His website is: www.williamlkatz.com

For more information on Thaddeus Stevens, you can visit the Thaddeus Stevens Society at http://thaddeusstevenssociety.com/ and the Thad Shop at http://www.thaddeusstevenssociety.com/ThadShop.html

I would appreciate the best sources that you would recommend on Stevens and Russian serfs.

Yes Indeed William Loren Katz:

Thank you once again for an education that cannot be acquired from any place but your desk.

I will be in touch with you.

Best regards,

Rose

Indian Voices