The Boris Johnson government, while censoring files, wants to commission an “official history” of the Troubles, Anne Cadwallader reports.

U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson during a cabinet meeting in February. (Pippa Fowles, No 10 Downing Street)

By Anne Cadwallader

Declassified UK

Jaws have dropped across Ireland at the British government’s intention to commission an official history of The Troubles. Those that have perhaps dropped fastest and furthest belong to the Livingstone and Whitters families.

Jaws have dropped across Ireland at the British government’s intention to commission an official history of The Troubles. Those that have perhaps dropped fastest and furthest belong to the Livingstone and Whitters families.

In April 1981, Elizabeth Livingstone’s youngest sister, Julie, aged 14, was shot dead walking home in Lenadoon, West Belfast. A soldier from the Royal Regiment of Wales had fired a plastic bullet gun from inside a Saracen armoured vehicle. Julie died a day later from head injuries.

Sixteen days before, Paul Whitters, aged 15, was shot with a plastic bullet in his native Derry. He had such catastrophic brain injuries that his parents were forced to make the heartbreaking decision, 10 days after he was shot, to switch off his life support in a Belfast hospital.

Both families discovered, decades after their bereavement, that the British government had decided not to declassify the official records on the circumstances of their deaths.

The file on Julie Livingstone’s death was closed in 2014 and remains so until 2064. Both her parents are already dead but, by 2064, all her 12 brothers and sisters will have died also.

In 2011, the official file on Paul Whitters’ killing was closed until 2059. Since then, half of it has been opened but 93 pages remain closed.

“What possible implications for British national security can there be in the killing of a 15-year-old child in Derry over 40 years ago?” asks his uncle, Tony Brown.

Secret Because It’s Secret

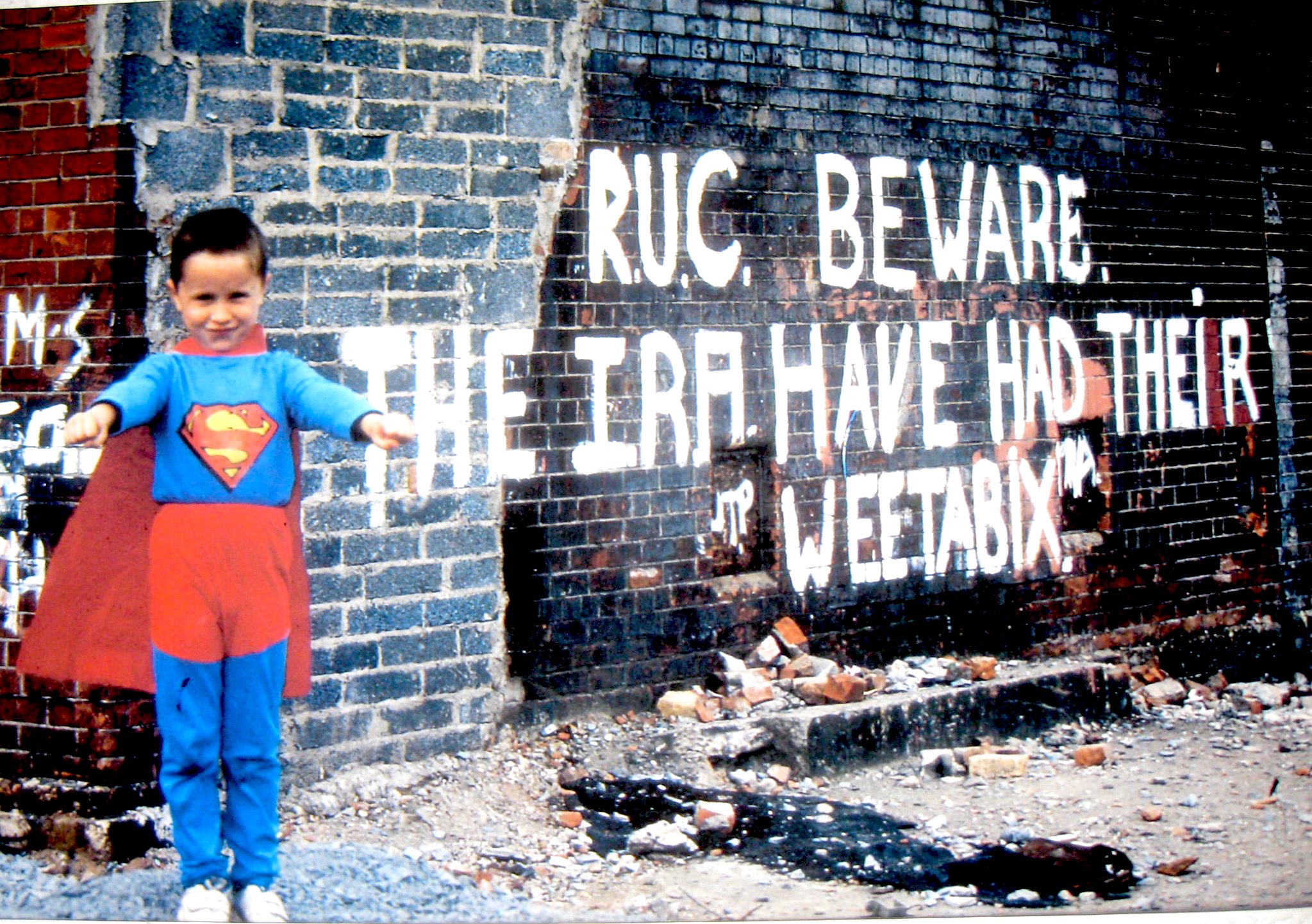

Belfast, 2013: The Troubles gone but not forgotten. (Diego Sideburns, Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

In a development worthy of Alice in Wonderland, it seems to the Whitters family that half the file is officially “secret” and the reason for keeping it “secret” must also remain “secret.”

“The circular stupidity of this argument has left us speechless. This is about my son who was shot at almost point-blank range at 15 years of age and about the cruel death of Julie Livingstone. They were just children”, says Helen Whitters.

She points out that neither family expects the names of those responsible to be released, freeing London from any data protection, health and safety or human rights obligations. The only possible remaining cause, they believe, is the notional one of national security.

While these families, and hundreds of others, are waiting for the truth, London announced it intends to commission historians to write an official account of the conflict. The Daily Telegraph last week revealed the plans were drawn up in response to fears that “IRA supporters are rewriting history.”

The narrative would focus on the role of the British government and army. One might be forgiven for recalling what Winston Churchill once memorably wrote that it would be “better” to leave the past to history “especially as I propose to write that history.”

‘Get Stuffed’

Broadcasting House, Belfast, headquarters of the BBC in Northern Ireland. (Man vyi, Wikimedia Commons)

Colin Harvey, professor of human rights at Queens University Belfast, said this week:

“The British were protagonists in the conflict …participants. And it seems like for the current British government, the truth hurts: they don’t like what’s emerging about the role of the British state.”

More succinct was Diarmaid Ferriter, professor of modern Irish history at University College, Dublin. Asked on BBC Northern Ireland’s “The View” program whether he would accept an invitation, if asked to participate, he replied “I think I’d say get stuffed.”

The Belfast Telegraph reports that amongst the historians being considered is Lord Bew, a sponsor of the Henry Jackson Society and inspiration behind the ill-fated Boston College oral history project.

Bew is also a former political adviser to the erstwhile leader of the Ulster Unionist Party, David, now Baron, Trimble.

Meanwhile, the files on Paul Whitters and Julie Livingstone are among dozens of others closed to researchers and historians. Some, most bizarrely, have been opened and then closed again, despite being widely publicised — while others have been opened, closed and then re-opened.

One example is File CJ 4/1647 (January 1976-July 1977) containing documents detailing complaints of brutality against the British army and the then Northern Irish police, the RUC. It has been closed to public access until 2064 — restricting the right of those who alleged brutality at the time to discover what was being said about them.

Another file is CJ 4/2841 (1976-1979) which details meetings and contacts between the British government and the largest loyalist paramilitary gang, the Ulster Defence Association. This was originally closed until 2052 on both health and safety grounds and because it contains personal information.

Closed for 100 Years

The U.K. National Archives at Kew. (Chris Reynolds, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

When Margaret Urwin, of the Justice for the Forgotten group, made a freedom of information request, hoping to get the file opened, her request was rejected and the date of closure was increased from 72 to 100 years.

Such requests are adjudicated by a supposedly independent watchdog at the National Archives. Its members are appointed by the culture secretary and include a former deputy head of MI5. They rubber stamp on average 99 percent of government censorship decisions.

It is worth stating that files such as these can, and often are, lawfully redacted under data protection rules where publishing a name might put someone at risk — but these are at least files known to exist.

In a different category are those whose very existence the British government has sought to conceal. Journalists such as Ian Cobain have written extensively about the Foreign Office unlawfully hoarding more than a million files of historic documents.

Those files are kept at a secret archive in a high-security government communications center in Buckinghamshire, north of London, where they occupy mile after mile of shelving.

Most of the papers are many decades old — some were created in the 19th century — and document British foreign relations throughout two world wars, the Cold War, withdrawal from empire and entry into the Common Market.

They have been kept from public view in breach of the Public Records Act that requires all government documents to become public once they are 20 years old unless the department has received permission from the lord chancellor to hold them for longer.

‘What Have They Got to Hide?’

Meanwhile, families like the Whitters and Livingstones are left to ponder why information on the deaths of their children are being withheld for decades.

“I felt we had done everything we could for Julie after three inquests had ruled she was a completely innocent victim,” said Elizabeth Livingstone of her younger sister.

“But when I found out about the hidden file, it brought all the pain back. Everyone who knew Julie will be dead by the time it is released. Your mind runs rampant. Why are they doing this? What have they got to hide?”

The Whitters family, likewise, has no idea why 93 pages of their file will be closed until 2084. “I’ve written to 22 different secretaries of state for Northern Ireland asking for information,” says Tony Brown, the dead boy’s uncle, a retired principal social worker.

“We have known the name of the RUC man who shot Paul, the name of the inspector who gave the order to fire and his superior since the inquest. That does not appear to have contaminated national security over the last forty years.

“Nothing will ever hurt us as much as Paul’s death but we are left bewildered by how the killing of a child forty years ago could impinge on national security. We cannot think of any other reason for withholding it.”

The dead boy’s mother, Helen, tells of how — the Christmas after Paul’s death — a police officer arrived at her door “handed us a bloodied bag of clothes, smirked and left.” That, she says, was the entirety of the RUC’s engagement with the family over the years.

“In a society which lays claim to democratic ideals of equality and transparency of government, denying families information on the deaths of their loved-ones makes a mockery of such notions,” Helen said.

The Harvard professor and author of three books on Northern Ireland, J. Bowyer Bell, after a lifetime studying British politics, wrote:

“A great deal of care, trouble, intimidation and influence has been expended to keep British secrets secret … Money, force, loyalty, greed, disinformation, the law, patriotism, fear …And if in the end nothing works, then firm denial, regardless of the evidence.”

The leopard does not appear to have changed its spots.

Anne Cadwallader has been a journalist in Ireland, North and South, for the last 40 years, working for the BBC, RTE, The Irish Press and Reuters. She is an advocacy case worker at the Pat Finucane Centre, a non-party political, anti-sectarian human rights group advocating a non-violent resolution of the conflict in Ireland.

This article is from Declassified UK.

no need to write an official history, just release the official secret files

History is always written by the victors.

So much secrecy in the files of such “democracies”.