The Congressional Budget Office charts a more rational approach to U.S. military spending, write Mandy Smithberger and William D. Hartung. But the proposed $1 trillion in savings should only be a starting point.

U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd JAustin arriving in Miami for the change of command at U.S. Southern Command, Oct. 29. (DoD, Lisa Ferdinando)

By Mandy Smithberger and William D. Hartung

TomDispatch.com

Even as Congress moves to increase the Pentagon budget well beyond the astronomical levels proposed by the Biden administration, a new report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has outlined three different ways to cut $1 trillion in Department of Defense spending over the next decade.

Even as Congress moves to increase the Pentagon budget well beyond the astronomical levels proposed by the Biden administration, a new report from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has outlined three different ways to cut $1 trillion in Department of Defense spending over the next decade.

A rational defense policy could yield far more in the way of reductions, but resistance from the Pentagon, weapons contractors, and their many allies in Congress would be fierce.

After all, in its consideration of the bill that authorizes such budget levels for next year, the Democratic-controlled House of Representatives recently voted to add $25 billion to the already staggering $750 billion the Biden administration requested for the Pentagon and related work on nuclear weapons at the Department of Energy. By any measure, that’s an astonishing figure, given that the request itself was already far higher than spending at the peaks of the Korean and Vietnam Wars or President Ronald Reagan’s military buildup of the 1980s.

In any reasonable world, such a military budget should be considered both unaffordable and deeply unsuitable when it comes to addressing the true threats to this country’s “defense,” including cyberattacks, pandemics, and the devastation already being wrought by climate change. Worst of all, providing a blank check to the military-industrial-congressional complex ensures the continued production of troubled weapon systems like Lockheed Martin’s exorbitantly expensive F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, which is typically behind schedule, far above projected costs, and still not considered effective in combat.

Changing course would mean real reform and genuine accountability, starting with serious cuts to a budget for which “bloated” is far too kind an adjective.

Three Options for Reductions

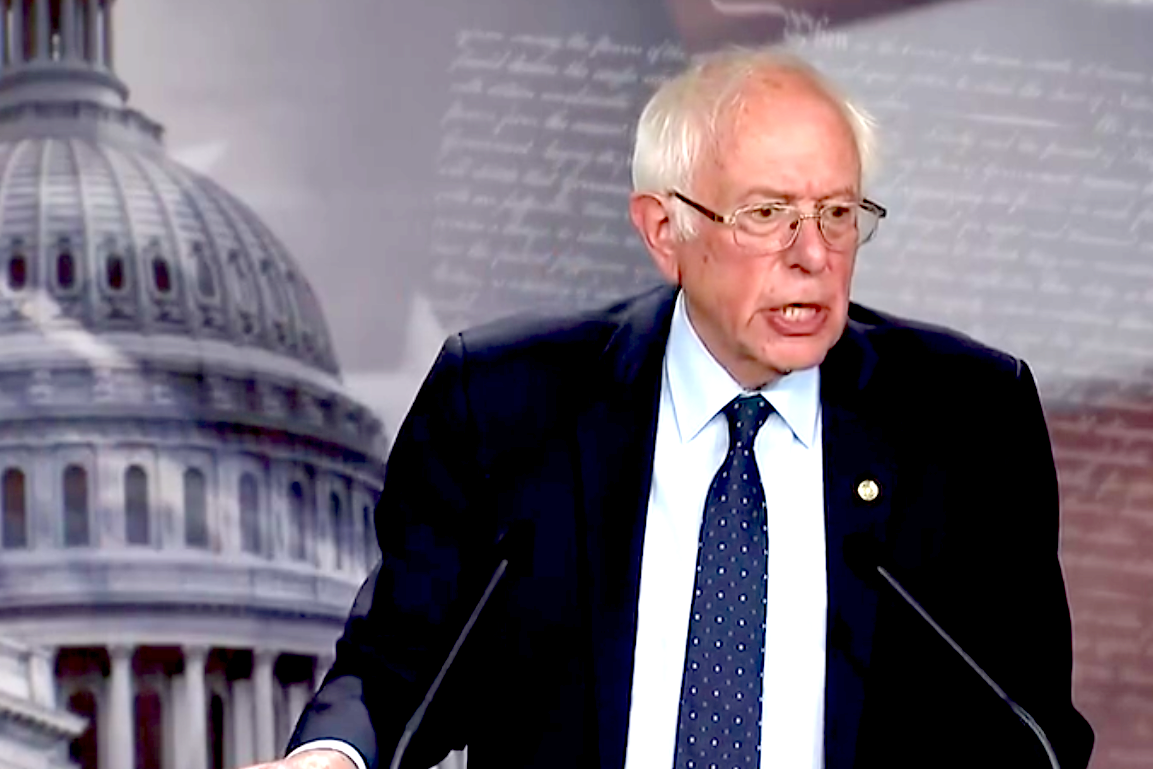

Sen. Bernie Sanders discussing U.S. domestic spending on Oct. 6. (Twitter, Bernie Sanders)

At the request of Senate Budget Committee Chair Bernie Sanders (I-VT), the CBO devised three different approaches to cutting approximately $1 trillion (a decrease of a mere 14 percent) from the Pentagon budget over the next decade. Historically, it could hardly be a more modest proposal. After all, without any such plan, the Pentagon budget actually did decrease by 30 percent) between 1988 and 1997.

Such a CBO-style reduction would still leave the department with about $6.3 trillion to spend over that 10-year period, 80 percent more than the cost of President Biden’s original $3.5 trillion Build Back Better proposal for domestic investments. Of course, that figure, unlike the Pentagon budget, has already been dramatically whittled down to half its original size, thanks to laughable claims by “moderate” Democrats like Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) that it would break the bank in Washington. Yet such critics of expanded social and economic programs rarely offer similar thoughts when it comes to the Pentagon’s far larger bite of the budgetary pie.

The options in the budget watchdog’s new report are anything but radical:

Option one would preserve the “current post-Cold War strategy of deterring aggression through [the] threat of immediate U.S. military response with the objectives of denying an adversary’s gains and recapturing lost territory.” The proposed cuts would hit each military service equally, with some new weapons programs slowed down and a few, as in the case of the B-21 bomber, cancelled.

Artist rendering of B-21 heavy stealth bomber under development for U.S. Air Force by Northrop Grumman. (Alan Radecki, Wikimedia Commons)

Option two “adopts a Cold War-like strategy for large nuclear powers of making aggression very costly and recognizing that the size of conventional conflict would be limited by the threat of a nuclear response.” That leaves nearly $2 trillion for the Pentagon’s planned “modernization” of the U.S. nuclear arsenal untouched, while relying more heavily on working with allies in conventional war situations than current strategy allows for. It would mean that the military might take longer to deploy in large numbers to a conflict.

Option three “de-emphasizes use of U.S. military force in regional conflicts in favor of preserving U.S. control of the global commons (sea, air, space, and the Arctic), ensuring open access to the commons for allies and unimpeded global commerce.” In other words, Afghan- or Iraq-style boots-on-the-ground U.S. interventions would largely be avoided in favor of the use of long-range and “over-the-horizon” weapons like drones, naval blockades, the enforcement of no-fly zones, and the further arming and training of allies.

But looking more broadly at the question of what will make the world a safer place in an era of pandemics, climate change, racial injustice, and economic inequality, reductions well beyond the $1 trillion figure embedded in the CBO’s recommendations would be both necessary and possible in a more reasonable American world. The CBO’s scenarios remain focused on military methods for solving security problems, assuring an all-too-narrow view of what might be saved by a new approach to security.

Nuclear Excess

The CBO, for instance, chose not to look at possible savings from simply scaling back (not even ending) the Pentagon’s $2-trillion, three-decades-long plan to build a new generation of nuclear-armed missiles, bombers, and submarines, complete with accompanying new warheads. Scaling back such a buildup, which will only further imperil this planet, could easily save in excess of $100 billion over the next decade.

One significant step toward nuclear sanity would be to adopt the alternative nuclear posture proposed by the organization Global Zero. That would involve the elimination of all land-based nuclear missiles and rely instead on a smaller force of ballistic missile submarines and bombers as part of a “deterrence-only” strategy.

Land-based, intercontinental ballistic missiles were accurately described by former Secretary of Defense William Perry as “some of the most dangerous weapons in the world.” The reason: a president would have only a matter of minutes to decide whether to launch them upon being warned of an oncoming nuclear attack by an enemy power. That would, of course, greatly increase the risk of an accidental nuclear war and the potential destruction of the planet prompted by a false alarm (of which there have been several in the past). Eliminating such missiles would make the world a far safer place, while saving tens of billions of dollars in the process.

Capping Contractors

An F-35A aircraft on display at Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, 2013. (Lockheed Martin)

While most people think about the Pentagon budget in terms of what it spends on new guns, ships, planes, and missiles, services are about half of what it buys every year. These are the contracts that go to various corporate “Beltway bandits” to consult with the military or perform jobs that could often be done more cheaply by federal employees. Both the Defense Business Board and the Pentagon’s own cost estimating office have identified service contracting as an area where there are significant opportunities for large-scale savings.

Last year, the Pentagon spent nearly $204 billion on various service contracts. That’s more than the budgets for the Departments of Health and Human Services, State, or Homeland Security. Reducing spending on contractors by even 15% would instantly save tens of billions of dollars annually.

In the past, Congress and the Pentagon have shown that just such savings could easily be realized. For example, a provision in a 2011 defense law simply capped such spending at 2010 levels. Government spending data shows that, in the end, it was reduced by $42 billion over four years.

Closing Unneeded Bases

While the Biden administration seeks to expand domestic infrastructure spending, the Pentagon has been desperate to shed costly and unnecessary military facilities. Both the Obama and Trump administrations asked Congress to authorize another round of what’s called base realignment and closure to help the Defense Department get rid of its excess capacity. The Pentagon estimates that it could save $2 billion annually that way.

The CBO report cited above explicitly excludes any consideration of such cost savings as politically unfeasible, given the present Congress. But considering the ways in which climate change is going to threaten current military basing arrangements domestically and globally, that would be an obvious way to go.

Another CBO report warns that the future effects of climate change — from rising sea levels (and flooding coastlines) to ever more powerful storms — will both reduce the government’s revenue and increase its mandatory spending, if its base situation remains as it is now. After all, ever fiercer tropical storms and hurricanes, as well as rising levels of flooding, are already resulting in billions of dollars in damage to military bases. Meanwhile, it’s estimated that, in the decades to come, more than 1,700 U.S. military installations worldwide may be impacted by sea-level rise. Future rounds of base closings, both domestic and global, should be planned now with the impact of climate change in mind.

Turning Around Congress, Fighting Off Lobbyists

U.S. congressional representatives touring the MC-130J Commando II aircraft at Cannon Air Force Base, N.M., in 2015. (U.S. Air Force. Chip Slack)

So far, boosting Pentagon spending has been one of the only things a bipartisan majority of this Congress can agree on, as indicated by that House decision to add $25 billion to the Pentagon budget request for Fiscal Year 2022. A similar measure is included in the Senate version, which it will debate soon. There are, however, glimmers of hope on the horizon as the number of members of Congress willing to oppose the longstanding practice of shoveling ever more funds at the Pentagon, no questions asked, is indeed growing.

For example, a majority of Democrats and members of the leadership in the House of Representatives supported an ultimately unsuccessful provision to strip some excess funds from the Pentagon this year. A smaller group voted to cut the department’s budget across the board by 10 percent. Still, it was a number that would have been unthinkable just a few years ago. That core group is only likely to grow in the years to come as the costs of non-military challenges like pandemics, climate change, and the financial impact of racial and economic injustice supplant traditional military risks as the most urgent threats to American lives and livelihoods.

Opposition to increased Pentagon spending is growing outside of Washington as well. An ever wider range of not just progressive but conservative organizations now support substantial reductions in the Pentagon budget. The challenge, however, is to translate such sentiments into a concerted, multifaceted campaign of public pressure that will move a majority of the members of Congress to stop giving the Pentagon a yearly blank check. A new poll from the Eurasia Group Foundation found that twice as many Americans now support cutting the Pentagon budget as support increasing it.

Any attempt to curb Pentagon spending will run up against a strikingly powerful arms industry that deploys campaign contributions, lobbyists, and promises of defense-related employment to keep budgets high. In this century alone, the Pentagon has spent more than $14 trillion, up to one half of which has gone to contractors. During those same years, the arms industry has spent $285 million on campaign contributions and $2.5 billion on lobbying, most of it focused on members of the armed services and defense appropriations committees that take the lead in deciding how much the country spends for military purposes.

The arms industry’s lobbying efforts are especially insidious. In an average year, it employs around 700 lobbyists, more than one for every member of Congress. The top five corporate weapons makers got a return of $1,909 in taxpayer funds for every dollar they spent on lobbying. Most of their lobbyists once worked in the Pentagon or Congress and arrived in the world of arms contractors via the infamous “revolving door.” Of course, they then used their relationships with their former colleagues in government to curry favor for their corporate employers. A 2018 investigation by the Project On Government Oversight found that, in the prior decade, 380 high-ranking Pentagon officials and military officers had become lobbyists, board members, executives, or consultants for weapons contractors within two years of leaving their government jobs.

A September 2021 study by the Government Accountability Office found that, as of 2019, the top 14 arms contractors employed more than 1,700 former military or Pentagon civilian employees, including many who had previously been involved in making or enforcing the rules for buying major weapons systems.

The revolving door spins both ways, with executives and board members of the major weapons makers moving into powerful senior positions in government where they’re well situated to help their former (and, more than likely, future) employers. The process starts at the top. Four of the past five secretaries of defense have also been executives, lobbyists, or board members of Raytheon, Boeing, or General Dynamics, three of the top five weapons makers that split tens of billions of dollars in Pentagon contracts annually. Both the House and Senate versions of the 2022 National Defense Authorization Act extend the periods of time in which those entering the government from such industries have to recuse themselves from decisions involving their former companies. Still, as long as the Pentagon continues to pluck officials from the very outfits driving those exploding budgets, we should all know more or less what to expect.

So far, the system is working — if you happen to be an arms contractor. The top five weapons companies alone split $166 billion in Pentagon contracts in Fiscal Year 2020, well over one-third of those issued by the Department of Defense that year. To give you some sense of the scale of all this — and our government’s twisted priorities — Lockheed Martin alone received $75 billion in Pentagon contracts in Fiscal Year 2020, nearly one and one-half times the $52.5 billion allocated for the State Department and the Agency for International Development combined.

Which Way Forward?

The Congressional Budget Office’s new report charts a path toward a more rational approach to Pentagon spending, but the $1 trillion in savings it proposes should only be a starting point. Hundreds of billions more could be saved over the next decade by reassessing our national security strategy, cutting back the Pentagon’s nuclear buildup, capping its use of private contractors, and scaling back the colossal sums of waste, fraud, and abuse baked into its budget. All of this could be done while making this country and the world a significantly safer place by shifting such funds to addressing the non-military risks that threaten the future of humanity.

Whether our leaders meet the challenges of today or continue to succumb to the power of the arms lobby is an open question.

Prediction: if there is a hot war we will find that billions, maybe trillions will have been spent on equipment and systems that don’t work or perform far less than promised. It will cause drastic changes in the way we build our equipment and scapegoats and new leaders will appear. Why the prediction, because the Senators and Congressman and the White House are more interested in spending and jobs than performance. Think how long it took to manufacture a B-17 in WWII and how long it takes to build a single plane today. I know the proponents of our MIC+ will have answers that are not likely to hold water.

“Option three “de-emphasizes use of U.S. military force in regional conflicts in favor of preserving U.S. control of the global commons (sea, air, space, and the Arctic), ensuring open access to the commons for allies and unimpeded global commerce.” In other words, Afghan- or Iraq-style boots-on-the-ground U.S. interventions would largely be avoided in favor of the use of long-range and “over-the-horizon” weapons like drones, naval blockades, the enforcement of no-fly zones, and the further arming and training of allies.”

All options are variants of “preserving U.S. domination”, and define that domination in very aggressive terms. Thus all options that Establishment can think about require arm race with powers that do not wish to depend on American good will, especially when the goodness of that will is questionable. Why China would resign itself to American capacity and readiness to impose a blockade? Aggressive domination, in any variant, leads to arms race.

The bloated nature of MIC implies that once the other powers, doomed to be “adversaries” if USA insists of being the sole hegemon, have somewhat comparable industrial capacity, arms race cannot be won. Russia can keep pace in the arms race in terms of technology — they do not develop all of them, but enough, China can match US spending in PPP terms already.

In other words, U.S. should re-work its goals, and negotiate arms limitations. Current “posture” aims to preserve the capacity to blackmail and loot, however lucrative, it is not sustainable.

Only a highly rational and humanistically-responsible commentator such as yourself could proffer such a sane and sensible advise to a US that acutely lacks such minds in this past few decades. But would there be any serious takers though ?

Then grow the gonads and confront them…

I just don’t see how ten-year reductions in Pentagon spending are going to help confront the climate and economic and social crises that we now face.

Perhaps by having much needed money spent where it really is needed???

It is more than that. Global warming, and a number of other issues, can be solved only through global cooperation. That requires a non-aggressive approach and treating other countries with mutual dignity and a good dose for introspection. Refrain from ridiculously selfish proposals like “we will cut on carbon emissions by decreasing European purchases of Russian natural gas, increasing their purchases of American liquified natural gas (more refreshing) and figuring something later”, as in conclusions of a recent Rogin’s editorial in WaPo. Arms race and associated sanctions and other sabotage, great or small, are bad for climate, both in international relations and the actual climate.