It should have been obvious to Bristol’s authorities that it was offensive to revere a slave trader in a public square, writes Jonathan Cook.

By Jonathan Cook

Jonathan-Cook.net

It is easy to forget how explicitly racist British society was within living memory. I’m not talking about unconscious prejudice, or social media tropes. I’m talking about openly celebrating racism in the public space, about major companies making racism integral to their brand, a selling-point.

It is easy to forget how explicitly racist British society was within living memory. I’m not talking about unconscious prejudice, or social media tropes. I’m talking about openly celebrating racism in the public space, about major companies making racism integral to their brand, a selling-point.

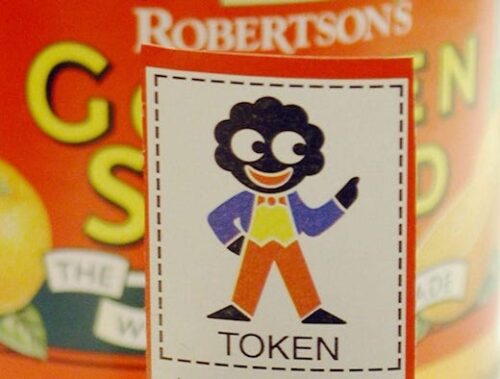

Roberston’s, Britain’s leading jam maker, made their orange marmalade sweeter to generations of (white) British children by associating it with a “golliwog.” One of the fondest memories I have of my childhood breakfasts was collecting golliwog tokens on the jar label. Collect enough and you could send away for a golliwog badge. More than 20 million badges were issued. I remember proudly wearing one.

Roberston’s, Britain’s leading jam maker, made their orange marmalade sweeter to generations of (white) British children by associating it with a “golliwog.” One of the fondest memories I have of my childhood breakfasts was collecting golliwog tokens on the jar label. Collect enough and you could send away for a golliwog badge. More than 20 million badges were issued. I remember proudly wearing one.

Most white children, of course, absorbed – with the unquestioning trust of a young, unformed mind – the racist assumptions behind those golliwog figures. There are still Britons, like this Conservative councillor in Bristol, who never grew up. They continue to celebrate their breakfast-time lessons in racism – and can count on a newspaper, like the Metro, to give their views an unchallenged airing.

Racism was not just a feature of my childhood breakfasts. Friends had golliwog dolls in their beds, and Little Black Sambo story books on their shelves. Leisure time was spent watching TV shows like the BBC’s Black and White Minstrels Show – black-up as family, round-the-campfire entertainment – or comedies like It Ain’t Half Hot Mum (with grinning, ridiculous locals providing the exotic backdrop to a nostalgic romp around the British empire) and Mind Your Language (with simple-minded “immigrants” from the former colonies struggling through English-language classes).

Racism was not just a feature of my childhood breakfasts. Friends had golliwog dolls in their beds, and Little Black Sambo story books on their shelves. Leisure time was spent watching TV shows like the BBC’s Black and White Minstrels Show – black-up as family, round-the-campfire entertainment – or comedies like It Ain’t Half Hot Mum (with grinning, ridiculous locals providing the exotic backdrop to a nostalgic romp around the British empire) and Mind Your Language (with simple-minded “immigrants” from the former colonies struggling through English-language classes).

Victims of Empire

Britain’s education system played its part too. History and other subjects took it as read that Britain had a glorious past in which it once ruled the world, spreading enlightenment and civilization to the dusky natives. The only significant event I can recall from lessons on Britain’s colonial involvement in India is the Black Hole of Calcutta, a dungeon so cramped with prisoners that many dozens suffocated to death one night in 1756. That event, from more than 200 years ago, was obviously explained to me with such impassioned horror by my teacher that it left an indelible scar on my memory.

Many years later, overlaid by my much later leftwing politics, I recalled the Black Hole deaths as referring to British crimes against the native Indian population, and saw it as a hopeful indication that British schools even in my time were beginning to address the terrors of colonialism.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’ 25th Anniversary Spring Fund Drive

But when I looked it up, I found my assumption about the episode was entirely wrong. It was native Indians rebelling against the rule of the East India Company, a trading corporation that became more powerful than the king through its pillage of India, who forced British mercenaries into the Black Hole. Paradoxically, the East India Company’s foot-soldiers –there to oppress the local population and plunder India’s resources – died in the very dungeon the firm had built to punish Indians.

History classes were designed to impress on me British victimhood even as Britain was in the midst of raping, pillaging and murdering its way around the globe.

Sales Versus Complaints

Until I researched this post, I had also assumed that Roberston’s quietly shelved the golliwog badge back in the early 1970s. But no. Apparently the badges were still available for children until 2002. In the tiniest of makeovers in the 1980s, Robertson’s reinvented the golliwog as a cuddly “golly.”

It is hard to imagine a spokeswoman for a major corporation – in this case, Rank Hovis McDougall – defending the use of the golliwog now as they did back in 2001:

We receive around 10 letters a year from people who object to the [golliwog] character. That compares to 45m jars of jam and mincemeat sold annually.

The scales of trade: 45 million jars a year weighed against 10 killjoys. Golliwogs were simply good for business, given the cultural climate that had been manufactured for the British public. In a way, you have to appreciate the corporation’s honesty.

The linked Guardian article is worth reading too. Less than 20 years ago the country’s only “liberal-left” newspaper felt quite able to report the dropping of Robertson’s golliwog character in faintly nostalgic terms, an example of “Gosh, how the times, they are a-changin’ ” journalism, instead of the unalloyed disapproval we would now expect.

Corporate Sloganeering

Those approaches contrast sharply, of course, with today’s sloganeering from Nike, Reebok, Amazon and many other corporations as they hurry to show their support for Black Lives Matter in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin late last month.

To the black community:

We see you.

We stand in solidarity with you.

This can no longer be the status quo. pic.twitter.com/LpE7HHp3qU— Reebok (@Reebok) May 30, 2020

Have the assumptions of the corporate world changed so dramatically over the past 18 years, or have their priorities remained exactly the same: to make money by making us identify with what they need to sell us?

Golliwogs no longer shift product. What does is empty corporate slogans about equal rights, humanity and dignity – as long as corporations don’t have to deal with inequality in their boardrooms, or, more importantly, recognize the humanity of laborers in their Third World factories or their local warehouses.

The Trade that Built Bristol

All of this is a prelude to discussing the pulling down at the weekend of a statue in Bristol to Edward Colston, a notorious slave trader in the late 17th century. He helped to build the city from the profits he and others made from trafficking human beings – people whose lives and suffering the traders considered as insignificant as the animals many of us consume today.

#Bristol statue of Edward Colston has been pulled down and pushed into the harbour during the #BlackLivesMattter march pic.twitter.com/ME1yxAhw7G

— BBC Radio Bristol (@bbcrb) June 7, 2020

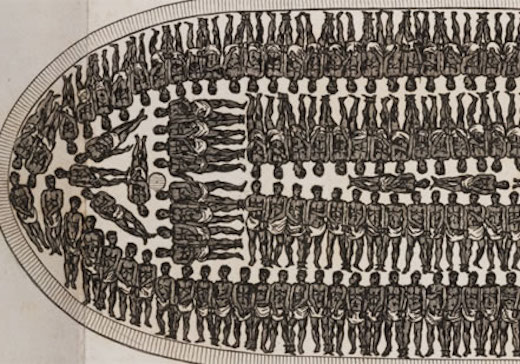

Slave traders like Colston headed a business that had only two possible outcomes for those who were its “product.”

For countless millions of Africans, the slave trade forced them into permanent servitude in conditions set by their white owner, who did not consider them human. For countless millions more, the slave trade meant death. Death if they resisted. Death if the traders lacked food for all of their human cargo. Death if the slaves fell ill in the appalling conditions in which they were transported. Death if their bodies could no longer take the punishment of their enslavement.

African slave ship diagram.

Colston’s slave trade – and related trades like the colonial plunder run by the East India Company – built cities like Bristol. They funded the British empire. These trades enriched a political class whose descendants are still educated in private schools venerating that ugly past – because those same schools produced the merchants who once ruled and pillaged the planet. The same children then go on to attend prestigious universities where they are still trained to rule and plunder the world — if now largely through transnational corporations.

Some even go on to become prime minister.

Spotlight on History

The ignominious removal of Colston statue’s and its dumping in Bristol’s harbor are being widely condemned from all sides of the narrow political spectrum: from Sajid Javid, until recently chancellor of the exchequer in the ruling Tory party, to Sir Keir Starmer, the leader of the opposition Labour Party.

The rationales for opposing this act of rebellion by ordinary people against the continuing veneration of slave traders and white supremacists are illuminating. They tell us more about how we are still shaped by our golliwog upbringings than we may care to admit. After all, by today’s standards Colston would qualify to stand trial in the Hague on charges of crimes against humanity and genocide.

Some have compared the tearing down of his statue to the 2001 destruction of the Bamyan statues in Afghanistan by the Taliban. Other see in it the equivalent of book-burning by the Nazis. But obviously the erasure of Colston’s statue in a shared public space – a central square in Bristol – neither disappears a work of art nor does it erase Colston from history.

Those who value the statue as a historical record – or even as a work of art – are fully entitled to dredge it up from the harbor and install it in a museum, ideally one dedicated to the horrors of the slave trade and British society’s long ignorance of its own imperial history and crimes.

Those who fear censorship or the erasure of historical knowledge should not worry either. They can still find out all about Colston in history books and on the internet. Here is his Wikipedia page. None of that has been erased or is ever likely to be.

In fact, far from erasing history, the protesters managed to shine a very bright spotlight on a part of British history our political elite would much rather was glossed over or ignored.

Commemoration Standards

Other critics suggest that it is wrong to impose modern standards and values on a man who died 300 years ago. And that if we did the same more widely, there would be no statues left in Britain’s city centers. It is the tyranny of political correctness, they argue. Instead, we should acknowledge that cities like Bristol would not exist without the trade that enriched it, and that the British public would not be able to enjoy our cities’ public parks and grandiose buildings.

Except Colston did not simply abide by the standards of his day, appalling as we view those standards now. There were abolitionists prominent when Colston was around. He made a choice, an economic choice to be on the wrong side of history. He made a decision to put profit before conscience, as many of us do to this day. He set a terrible example to those around him, as many of us do now. His is an influence we should wish to oppose and diminish, not venerate and emulate.

True, there is no point in judging Colston himself all these centuries later. He was a product of his time and class. But we should judge those who wish retrospectively to approve a decision taken in the 1890s to erect a statue to Colston, more than 170 years after he died, when slavery had long ago been abolished in the U.K. We should also judge those who think it fine to gratuitously insult today, through the elevation of a statue, the many people in Bristol whose ancestors suffered unimaginable horrors and suffering because of Colston. That has nothing to do with democracy; it is race hatred.

If you listen to Sajid Javid and Keir Starmer, you might imagine the reason UK cities host statues of slave traders and white supremacists is because people voted for them to be there. It's incitement not democracy to impose these criminals on public space https://t.co/WLI2q3d68y

— Jonathan Cook (@Jonathan_K_Cook) June 9, 2020

The choice we can make now is to celebrate in our most public, most collective, shared spaces the values we hold dearest – not values that appeared acceptable to our ancient forebears. No one would oppose Russians pulling down a statue of Stalin, or Germans destroying statues of famous Nazis. Nor, we should note, did most westerners object in 2003 when a group of Iraqis were helped – by U.S. and U.K. troops after an illegal invasion – to pull down a giant statue of Saddam Hussein on primetime TV.

The public square is public. It should represent values that can be embraced by wider society, not just those who cling to a narrow, ugly and outdated idea of Britishness – or still cherish, like our Bristol councillor, the role of slave traders like Colston in building his city.

Shared Values in Public Space

Even without Colston, Britain will continue to commemorate its imperial past – and obfuscate its historic crimes. Books and art works in this vein litter libraries and art galleries across the country. But those are different spaces from the public square. We choose to read a book or enter a gallery, but we cannot avoid our city centers. By definition, a statue in a public park or square commemorates and venerates the person it depicts and the actions associated with them. Books and art galleries are where we contemplate, study and discuss. If an art exhibition is well curated, the products of imperial and colonial history should not glorify the past to visitors, but clarify and contextualize it.

Rather than oppose the protesters for targeting Colston’s statue, or worry about the fate of similar statues, critics should consider why it is that so many British cities are stuffed with art works commemorating Britons who committed war crimes and crimes against humanity.

What does that say about our supposedly glorious past or about the wealth that paid for our cities? Is that a history we should continue to glorify? Should we shrink from the truth, pretending it never happened? Or is time we confronted the past honestly? Should we not wonder what it tells us about the present that we and our parents have been so insensitive to the hostile spaces we created in our major cities for those descended from the victims of our imperial crimes?

And even more challenging, should we not wonder how far we have actually moved on from the imperial “adventures” of slave traders like Colston? Are modern Britain’s foreign “adventures” – now called “interventions” – in countries like Afghanistan and Iraq so very different? Like Colston, we have tried to shape black and brown people’s destinies in our interests, with little regard to the death and suffering we have inflicted on them in the process. Exposing Colston’s crimes hints at the crimes to which we are party too.

Fear of the ‘Mob’

The concerns of those opposed to the pulling down of the Colston statue aren’t really about erasure of history or about anachronistic values. Their worry is located elsewhere.

For some it is the sense that a part of our collective nostalgia, our evenings warmed by a cathode tube as we watched “It Ain’t Half Hot Mum,” with us imagining that our Britishness – our identity, culture and institutions – represented something wholesome and good has been snatched away. We do not want to feel bad, so we cling on the past as though it were good.

Our cuddly golliwog has been kidnapped from our bed. How will we ever be able to go back to sleep?

But for others, I think, the concern is more contemporary than nostalgic. It is sublimated into the criticisms of Javid and Starmer that the crowds who pulled down the statue were lawbreakers, they were violating the democratic process, they were taking the law into their own hands, they were unleashing chaos and anarchy.

I grew up in Bristol. I detest how Edward Colston profited from the slave trade.

But, THIS IS NOT OK.

If Bristolians wants to remove a monument it should be done democratically – not by criminal damage. https://t.co/Wfz47zQQZU

— Sajid Javid (@sajidjavid) June 7, 2020

There is an obvious rejoinder. People in Bristol had spent many years trying to get the statue of Colston taken down through democratic means. They should not have needed to. It should have been obvious to the city’s authorities that it was offensive to revere a slave trader in a public square. The city should have taken action without prompting. Instead it did nothing.

It is a sign of the absolute failure of the democratic process – its calcification – that popular pressure could not bring about the removal of Colston’s statue. Had Bristol’s councillors really been sensitive to the issue, had the local media really represented the values we all profess to believe in, Colston’s statue would have been removed long ago. The lack of any urgency to end his elevated status in Bristol only emphasizes how Britain’s political class actually relates to imperialism and colonialism.

Stripped of all rationalizations, what this is really about, once again, is a fear of the mob.

Progress Through Protest

In his TV series “A House Through Time,” historian David Olusoga has been documenting Bristol’s history through a single grand house, built on money earnt from the slave trade. Last week he considered the period when it was the abode of John Haberfield. In the early 19th century Haberfield twice had a role – first as Bristol council’s legal adviser and then as mayor – in dealing with activists who would soon become the Chartists. They were the “mob” of that time who believed political corruption should end and that they, and not just the gentry, should have the vote.

Bristol’s leaders tried to jail the ringleaders in 1831 but that provoked larger demonstrations. The protesters took over Queen’s Square. Notably, paintings from the time disapprovingly show a drunken man carousing on top of a statue to a venerated public figure (Colston’s statue had yet to be erected). Bristol’s leaders responded by sending in the dragoons, the police force of the day. The dragoons charged towards the crowds on their horses, using their sabres to cut down dozens of the protesters for demanding a right we all take for granted today. Some 100 protesters were put on trial, and four men hanged, despite a petition from 10,000 of Bristol’s residents appealing to the monarch for clemency.

It seems Bristol’s political class today are little more responsive to the popular will than they were 200 years ago.

The point is that the gains made by ordinary people, and conceded so reluctantly by the Establishment, always came through confrontation. Rights were won because of events termed “riots,” because of popular protest, because of disobedience. Protest – violent and non-violent, explicit and threatened – was at the root of everything we now identify as progress.

Comforting Illusions

It is a comforting illusion that things today are so very different from 1831. We want to believe our voice now counts, that we have the power, that we are in charge, even though the vote our ancestors struggled so hard for has been stripped of value, our voices silenced. We are given a choice between two political parties equally captured by corporate money and interests.

We want to believe we have a free press even though the media is owned by billionaires. Its job is to keep us uninformed, docile, disorganized and divided. We want to believe that our police forces are there to serve, even when they prevent demonstrations and use violence against us (and against some of us more than others). We want to believe our societies no longer exploit and enslave, our willful blindness helped by corporations that keep modern slavery out of sight in far-off lands. Goods are sold to us on the basis of the deception that all lives matter.

All lives will matter when the weakest among us, the poorest, the most oppressed and the most exploited are given the chance for dignity and the right to flourish. That cannot happen when we live in deeply unequal societies, when we reward bankers before nurses and teachers, and when we refuse to address the historical injustices that continue to shape both our understanding of the world we live in and our opportunities to succeed.

Colston and his statue represent everything ugly and debased about our past and our present. If British leaders are still in thrall to the poison of our imperial history, then ordinary people must show the way through protest, defiance and disobedience – as they have done down through the ages. As they did once again at the weekend.

Jonathan Cook is a freelance journalist based in Nazareth.

This article is from his blog Jonathan Cook.net.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Contribute to Consortium News’ 25th Anniversary Spring Fund Drive

Donate securely with  PayPal here.

PayPal here.

Or securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

I agree with Jonathan. A statue to a slaver is hideous. However, as general policy–as in the tearing down a statue when the crowd doesn’t like it, would warrant all monuments to built in a temporary fashion.

I read an excellent book by a Chinese lady that had been through the ‘Great Leap Forward’ in the 1950’s. She was of the academic class, and collected Ming Dynasty pottery. They left her alone for awhile, then finally a gang of very young angry testosterone youths forced into her apartment and busted everything up–all in the name of the Communist revolution. They didn’t even know what the Ming Dynasty was. Reminds me of those fanatics smashing Palmyra a few years ago.

Mark Stanley. Thanks for your insightful comment. I’ll add something here, tearing down symbols be they statues, art works et cetra. Will that issue be the next thing we read about in the news? For example; should the Nazi submarine U boats be on display and people pay for a tour? I for one did a walk thru on the U 505,

it was a wonderful experience. Are we obliged to strike out against this symbol? Five thousand German U-boat sailors went to the bottom, most of whom, I’d guess, never read Mein Kampf, took a wife or had a lover. How many are in Arlington Cemetery who never read the US Constitution or Bill of Rights? These soldiers, Naval or otherwise, fought for their countries, trusted leadership over talk and a lot of words. RIP one and all of them. Would we as a nation revile statutes of General Ulysses S. Grant? who was responsible for salting rich black soils so as to weaken the confederates by starving them? As for me, this whole matter is preposterous. I’m certainly not a Nazi, never had an inkling that the south should secede from the north but I do respect and honor all soldiers everywhere who fought because they were asked to defend their homeland. They and their leaders did what they thought was right during that unique historical period they were in. Keep the statues, keep the flags and keep the perspective on historical dedications and the memories in tact. This is (still) a free country here in the US of A , while it lasts !

I can understand the quiet erasing of a statue of someone like Colsten as his only claim to fame is being a highly successful slaver. But what do you do about other people who have claims to fame far beyond the unpopular slave owner existence? Many Americans from the pre-Civil War period owned slaves. Washington, Jefferson are two that come immediately to mind. Do we erect statues to Washington because he owned slaves? No. It’s because as a general and a politician, he deserves the moniker, father of the United States. What I’d like to know is why hasn’t the Edmund Pettis bridge been renamed? He was a jerkwad if there ever was one.

The statues – regardless of whom/what they represent, regardless whether we like them or not, are part of our history and tearing them down serves no purpose.

Tearing the statues down would be akin to denying the existence of the prejudices held by the figures represented.

Only racists venerate racists and only racists feel that monuments to past or present racist ideologies deserve a presence in a public space. If the preservation of racist history is so important we need placards on these statues detailing the horrors that were committed by such slave traders including the kidnapping, ethnic cleansing, land and resource theft committed by white ‘thugs’, murderers, racists, and rapists that made Britain and America so ‘great’. This way the context of this history would serve as a reminder to all of the horrors of present and past oppression.

Thank you Mr Cook for this most apposite and truthful piece.

As a child of the late 1940s-1950s England, a father who was racist to his core (he’d been part of the UK military controlling the inhabitants of the Raj in the 1930s as had his father – both were other ranks, not officers, as befitted their working class realities). For my father w(ily)o(riental)g(entlemen)s began at Calais (so he said). Thankfully he was unloving and unlovable (as were his beliefs about the world), but I recall the “golliwogs.” Even in deepest darkest rural England.

While reading Mr Cook’s article three realities came to mind: Tonypandy – 1910 (one striking miner killed by a Po-lice baton) when Churchill sent in the army (no one was shot, although that was the story at the time and later). The police turned out to be (what a surprise) much more brutal toward the striking miners than the soldiers; The Windrush Generation – 1950s UK and British Caribbeans were invited to/came to live in the UK. In the early 2000s (?) the Maybot (Teresa May), at the time Home Office Minister, I believe, ordered the documentation – mostly passenger manifests – of the British Caribbeans’ arrival destroyed. And then they started to be deported….. The Chagos Islanders – including those living on Diego Garcia (their Home land) – were essentially sold off (their homelands anyway) to the USA under the Wilson govt – Labour – (to avoid having to send troops to Vietnam?) in the 1970s. The Chagossians were NOT asked if they would agree to being removed from their homes, lands and animals. Of course not. The Islanders were summarily “evacuated” to Mauritius without their belongings, dumped there and have striven ever since to return home. BUT the US refuses to give up its base there (built on the Chagossians’ lands) and the Brits (under the Maybot) stuck up the 2 finger “F*** you” to the ICC/ICJ’s decision for the Chagossians in 2018/19.

Plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose. The wealthy upper class Brits and their sycophantic cronies (comme the Snatcher) remain the same racist, orientalist, imperialists they have been since the 12C (when they first invaded Ireland and stayed).

And even Churchill himself – except during the “hero of democracy” period of WWII which represented about five percent of his more than ninety years – was not an admirable figure, not at all. Charismatic and very talented as a speaker and writer, but not admirable. He did not stand for great principles, even though he used great words.

His talents were dedicated to serving domination and control.

He absolutely relished empire and imperialism.

And empire is the polar opposite of democracy. Closely akin to slavery and dictatorship.

Churchill was willing to be quite brutal in protecting or expanding the empire. He never flinched from killing.

He expressed contempt for many other peoples and their ways, and on many occasions. Being quite sarcastic at times.

The heroic parliamentary statue basically uses a tiny fraction of his life to make him seem to be what he was not. He was not at all an admirer of democracy, offering some very sneering words about it during his career.

“Colston and his statue represent everything ugly and debased about our past and our present. If British leaders are still in thrall to the poison of our imperial history, then ordinary people must show the way through protest, defiance and disobedience – as they have done down through the ages. As they did once again at the weekend.”

Quite powerful, and I think entirely right.

Statues of this nature do need pulling down.

You could almost view the act as a public baptism towards entering a better future.

And I say that as someone with considerable reverence towards history and its commemoration.

Yes, slavery is part of history, but the kind of monuments that should be erected are the kind we see nowhere.

Along the lines of Rodin’s Burghers of Calais.

Washington has no great monument to slavery. I don’t think the Lincoln Memorial qualifies at all. Lincoln did not fight the Civil War over slavery. He hated the institution but was willing to see it remain if it meant peace. He said so himself.

A bas relief of that slave ship deck illustration (above) would be mighty suitable

Yet Washington has many monuments to many great slaveholders: Washington (his will freed his slaves but only following his own and his wife’s death), Jackson (right in that Lafayette Square location Trump immortalized – Jackson of course is infamous too for the brutal Trail of Tears), Madison, George Mason (more than a hundred slaves including children), and the greatest rogue of all, Thomas Jefferson (more than two hundred slaves, never earned his own living, and died a bankrupt owing friends money he borrowed – he also openly wrote in “Notes from Virginia” of black inferiority and supported Napoleon in trying to end the black rebellion in Haiti).

The mob made a good decision today, but can we trust the mob to make a good decision tomorrow? As imperfect as our democracies are they are still the way to make these kinds of decisions.

“Colston and his statue represent everything ugly and debased about our past and our present. ”

So does the imprisonment and torture of Julian Assange.

Indeed. The clearest public evidence of the brutality of the American empire.

You simply cannot have an empire without brutality. Its very nature parallels, closely in many respects, the institution of slavery.

Of course, the millions of bodies abroad from America’s imperial wars since WWII are even more powerful evidence, but Americans don’t see the Pentagon’s handiwork for the most part.

The estimates run from about eight to twenty million killed in America’s series of wars and coups and incursions, and the country is still busily at it in at least half a dozen places.

Amen.

“Colsten and his statue represent everything ugly and debased about our past and our present”

So does the imprisonment of Julian Assange.

@John Chuckman

And the clearest public evidence of the continuious brutality of the former British Empire.

A perfect riposte. Not a word I could disagree with. I only fear that when the Mob takes control, dictators emerge in their wake. If only the privileged could see it coming, and instead institute serious reform. Unfortunately, history tells us they never learn until it’s too late.

Initial versions of the Noddy series of books by Enid Blyton had golliwogs as characters, but newer versions, along with a new story written by Blyton’s granddaughter Sophie Smallwood in 2009, have since replaced them with other characters. A faction of those who grew up with the books, or at least the original editions with the golliwogs, have complained of the newer, golliwog-free editions pandering to political correctness.

What are the chances that Mr. Cook will be accused of being politically-correct in his description of the Robertson’s “golly”? I don’t disagree with him on this, but still.

And likewise went the statue of Robert E. Lee whose South was built from the slave trade.

Excellent column

Does anyone remember Margaret Thatcher’s daughter losing her job in the UK for calling French tennis player Gael Monfils a gollywog??

I think it was actually Jo-Wilfried Tsonga who got called “golliwog”.