Danny Sjursen finds America’s Moro War – which included misleading accounts of progress by military commanders — grimly familiar in the context of today’s Afghan War.

By Danny Sjursen

TomDispatch.com

For a decade and a half, the U.S. Army waged war on fierce Muslims in a remote land. Sound familiar?

For a decade and a half, the U.S. Army waged war on fierce Muslims in a remote land. Sound familiar?

As it happens, that war unfolded half a world away from the Greater Middle East and more than a century ago in the southernmost islands of the Philippines. Back then, American soldiers fought not the Taliban, but the Moros, an intensely independent Islamic group with a similarly storied record of resisting foreign invaders. Precious few today have ever heard of America’s Moro War, fought from 1899 to 1913, but it was, until Afghanistan, one of America’s longest sustained military campaigns.

Popular thinking assumes that the U.S. wasn’t meaningfully entangled in the Islamic world until Washington became embroiled in the Islamist Iranian revolution and the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, both in the pivotal year of 1979. It simply isn’t so. How soon we forget that the Army, which had fought prolonged guerrilla wars against tribal Native Americans throughout the 19th century, went on — often led by veterans of those Indian Wars — to wage a counterinsurgency war on tribal Islamic Moros in the Philippine Islands at the start of the new century, a conflict that was an outgrowth of the Spanish-American War.

That campaign is all but lost to history and the collective American memory. A basic Amazon search for “Moro War,” for instance, yields just seven books (half of them published by U.S. military war colleges), while a similar search for “Vietnam War” lists no less than 10,000 titles. Which is curious. The war in the Southern Philippines wasn’t just six years longer than conventional American military operations in Vietnam, but also resulted in the awarding of 88 Congressional Medals of Honor and produced five future Army chiefs of staff. While the insurgency in the northern islands of the Philippines had fizzled out by 1902, the Moro rebels fought on for another decade. As Lieutenant Benny Foulois — later a general and the “father” of Army aviation — reflected, “The Filipino insurrection was mild compared to the difficulties we had with the Moros.”

A group of Filipino combatants laying down their weapons during their surrender, c. 1900. (Wikimedia Commons)

Here are the relevant points when it comes to the Moro War (which will sound grimly familiar in a 21stcentury forever-war context): the United States military shouldn’t have been there in the first place; the war was ultimately an operational and strategic failure, made more so by American hubris; and it should be seen, in retrospect, as (using a term General David Petraeus applied to our present Afghan War) the nation’s first “generational struggle.”

More than a century after the U.S. Army disengaged from Moroland, Islamist and other regional insurgencies continue to plague the southern Philippines. Indeed, the post-9/11 infusion of U.S. Army Special Forces into America’s former colony should probably be seen as only the latest phase in a 120-year struggle with the Moros. Which doesn’t portend well for the prospects of today’s “generational struggles” in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, and parts of Africa.

Welcome to Moroland

Soldiers and officers streaming into what they dubbed “Moroland” at the turn of the century might as well have been entering Afghanistan in 2001-2002. As a start, the similarity between the Moro islands and the Afghan hinterlands is profound. Both were enormous. The Moro island of Mindanao alone is larger than Ireland. The more than 369 southern Philippine islands also boasted nearly impassable, undeveloped terrain — 36,000 square miles of jungle and mountains with just 50 miles of paved roads when the Americans arrived. So impenetrable was the landscape that soldiers called remote areas the “boondocks” — a corruption of the Tagalog word bundok — and it entered the American vernacular.

Please Make Your End-of-Year Donation Today.

The Moros (named for the Muslim Moors ejected from Spain in 1492) were organized by family, clan, and tribe. Islam, which had arrived via Arab traders 1,000 years earlier, provided the only unifying force for the baker’s dozen of cultural-linguistic groups on those islands. Intertribal warfare was endemic but more than matched by an historic aversion to outside invaders. In their three centuries of rule in the Philippines, the Spanish never managed more than a marginal presence in Moroland.

Vintage Moroland weapons on display at the Quirino-Syquia Museum in Vigan, Ilocos Sur, Philippines. (Alternativity, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

There were other similarities. Both Afghans and Moros adhered to a weapons culture. Every adult male Moro wore a blade and, when possible, sported a firearm. Both modern Afghans and 19th-century Moros often “used” American occupiers as a convenient cudgel to settle tribal feuds. The Moros even had a precursor to the modern suicide bomber, a “juramentado” who ritualistically shaved his body hair and donned white robes before fanatically charging to his death in blade-wielding fury against American troops. So fearful of them and respectful of their incredible ability to weather gunshot wounds were U.S. soldiers that the Army eventually replaced the standard-issue .38 caliber revolver with the more powerful Colt .45 pistol.

When, after defeating the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay and forcing the quick surrender of the garrison there, the U.S. annexed the Philippines via the 1898 Treaty of Paris, the Moros weren’t consulted. Spanish rule had always been tenuous in their territories and few Moros had even heard of Paris. They certainly hadn’t acceded to American rule.

Early on, U.S. Army officers deployed to Moroland contributed to the locals’ sense of independence. General John Bates, eager to focus on a daunting Filipino uprising on the main islands, signed an agreement with Moro leaders pledging that the U.S. would not meddle with their “rights and dignities” or “religious customs” (including slavery). Whatever his intentions, that agreement proved little more than a temporary expedient until the war in the north was won. That Washington saw the relationship with those tribal leaders as analogous to its past ones with “savage” Native American tribes was lost on the Moros.

Though the Bates agreement held only as long as was convenient for American military and political leaders, it was undoubtedly the best hope for peace in the islands. The limited initial U.S. objectives in Moroland — like the similarly constrained goals of the initial CIA/Special Forces invasion of Afghanistan in 2001— were so much wiser than the eventual expansive, futile goals of control, democratization, and Americanization in both conflicts. U.S. Army officers and civilian administrators couldn’t countenance for long Moro (and later Afghan) practices. Most advocated the full abrogation of the Bates agreement. The result was war.

Different Officers, Views & Strategies

The pacification of Moroland was run — like that in the “war on terror” — mostly by young officers in remote locales. Some excelled, others failed spectacularly. Yet even the best of them couldn’t alter the strategic framework of imposing “democracy” and the “American way” on a distant foreign populace. Many did their best, but due to the Army’s officer rotation system, what resulted was a series of disconnected, inconsistent, alternating strategies to impose American rule in Moroland.

When the Moros responded with acts of banditry and random attacks on American sentries, punitive military expeditions were launched. In the first such instance, General Adna Chaffee (later Army chief of staff) gave local Moro tribal leaders a two-week ultimatum to turn over the murderers and horse thieves. Understandably unwilling to accept American sovereignty over a region their Spanish predecessors had never conquered, they refused — as they would time and again in the future.

American soldiers battling the Moro rebels, 1902. (Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons)

Colonel Frank Baldwin, who led the early campaign, applied brutal, bloody tactics (that would prove familiar indeed in 21st-century Afghanistan) to tame the Moros. Some younger Army officers disagreed with his approach, however. One, Captain John Pershing, complained that Baldwin “wanted to shoot the Moros first and give them the olive branch afterwards.”

Over the next 13 years of rotating commanders, there would be an internal bureaucratic battle between two prevailing schools of thought as to how best to pacify the restive islands — the very same struggle that would plague the post-9/11 “war on terror” military. One school believed that only harsh military responses would ever cow the warlike Moros. As General George Davis wrote in 1902, “We must not forget that power is the only government that [the Moros] respect,” a sentiment that would pervade the book that became the U.S. Army’s bible when it came to the 21st-century “Arab mind.”

Others, best personified by Pershing, disagreed. Patiently dealing with Moro leaders man-to-man, maintaining a relatively light military footprint, and accepting even the most “barbaric” local customs would, these mavericks thought, achieve basic U.S. goals with far less bloodshed on both sides. Pershing’s service in the Philippines briefly garnered attention during the 2016 presidential campaign when candidate Donald Trump repeated a demonstrably false story about how then-Captain John Pershing (future commanding general of all U.S. forces in World War I) — “a rough, rough guy” — had once captured 50 Muslim “terrorists,” dipped 50 bullets in pig’s blood, shot 49 of them, and set the sole survivor loose to spread the tale to his rebel comrades. The outcome, or moral of the story, according to Trump, was that “for 25 years, there wasn’t a problem, OK?”

Well, no, actually, the Philippine insurgency dragged on for another decade and a Muslim-separatist rebellion continues in those islands to this day.

In reality, “Black Jack” Pershing was one of the less brutal commanders in Moroland. Though no angel, he learned the local dialect and traveled unarmed to distant villages to spend hours chewing betel nut (which had a stimulating effect similar to modern Somali khat) and listening to local problems. No doubt Pershing could be tough, even vicious at times. Still, his instinct was always to negotiate first and only fight as a last resort.

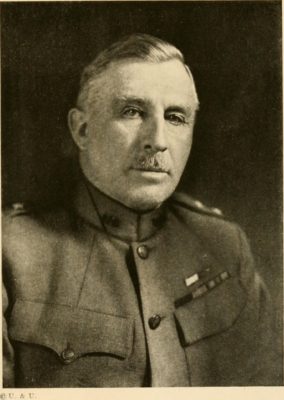

General Leonard Wood. (Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons)

When General Leonard Wood took over in Moroland, the strategy shifted. A veteran of the Geronimo campaign in the Apache Wars and another future Army chief of staff — a U.S. Army base in Missouri is named after him — he applied the scorched earth tactics of his Indian campaigns against the Moros, arguing that they should be “thrashed” just as America’s Indians had been. He would win every single battle, massacring tens of thousands of locals, without ever quelling Moro resistance.

In the process, he threw out the Bates agreement, proceeded to outlaw slavery, imposed Western forms of criminal justice, and — to pay for the obligatory American-style roads, schools, and infrastructure improvements — imposed new taxes on the Moros whose tribal leaders saw all of this as a direct attack on their social, political, and religious customs. (It never occurred to Wood that his taxation-without-representation model was also inherently undemocratic or that a similar policy had helped catalyze the American Revolution.)

The legal veneer for his acts would be a provincial council, similar to the American Coalition Provisional Authority that would rule Iraq after the 2003 U.S. invasion. That unelected body included Wood himself (whose vote counted twice), two other Army officers, and two American civilians. In his arrogance, Wood wrote to the American governor of the Philippines, future President William Howard Taft: “All that is necessary to bring the Moro into line and to start him ahead is a strong policy and vigorous enforcement of the law.” How wrong he would be.

Career advancement was Leonard Wood’s raison d’être, while knowledge about or empathy for the Moro people never ranked high on his list of priorities. One of his subordinate commanders, Major Robert Bullard — future commander of the 1st Infantry Division in World War I — noted that Wood exhibited “a sheer lack of knowledge of the people, of the country… He seemed to want to do everything himself without availing himself of any information from others.”

His tactical model was to bombard fortified Moro villages — “cottas” — with artillery, killing countless women and children, and then storm the walls with infantrymen. Almost no prisoners were ever taken and casualties were inevitably lopsided. Typically, in a campaign on the island of Jolo, 1,500 Moros (2 percent of the island’s population) were killed along with 17 Americans. When the press occasionally caught wind of his massacres, Wood never hesitated to lie, omit, or falsify reports in order to vindicate his actions.

When his guard came down, however, he could be open about his brutality. In a macabre prelude to the infamous U.S. military statement in the Vietnam era (and its Afghan War reprise) that “it became necessary to destroy the village in order to save it,” Wood asserted: “While these measures may appear harsh, it is the kindest thing to do.” Still, no matter how aggressive the general was, his operations never pacified the proud, intransigent Moros. When he finally turned over command to General Tasker Bliss, the slow-boiling rebellion was still raging.

His successor, another future Army chief (and current Army base namesake), was a far more cerebral and modest man, who later would help found the Army War College. Bliss preferred Pershing’s style. “The authorities,” he wrote, “forget that the most critical time is after the slaughter has stopped.” With that in mind, he halted large-scale punitive expeditions and prudently accepted that some level of violence and banditry in Moroland would be the reality of the day. Even so, Bliss’s “enlightened” tenure was neither a morality play nor a true strategic success. After all, like most current American generals addicted to (or resigned to) “generational war,” he concluded that a U.S. military presence would be necessary indefinitely.

After his (relatively) peaceful tour, Bliss predicted that “the power of government would, stripped of all misleading verbiage, amount to the naked fact that the United States would have to hold the larger part of the people by the throat while the smaller part governs it.” That vision of forever war haunts America still.

The Bud Dajo Massacre

Behind the veil of road-building, education, and infrastructure improvements, American military rule in Moroland ultimately rested on force and brutality. Occasionally, this inconvenient truth manifested itself all too obviously, as in the 1906 Bud Dajo massacre. Late in 1905, Major Hugh Scott, then the commander on Jolo and another future Army chief, received reports that up to 1,000 Moro families — in a tax protest of sorts — had decided to move into the crater of a massive dormant volcano, Bud Dajo, on the island of Jolo. He saw no reason to storm it, preferring to negotiate. As he wrote, “It was plain that many good Americans would have to die before it could be taken and, after all, what would they be dying for? In order to collect a tax of less than a thousand dollars from savages!” He figured that life on the mountaintop was harsh and most of the Moros would peacefully come down when their harvests ripened. By early 1906, just eight families remained.

Then Scott went home on leave and his pugnacious, ambitious second-in-command, Captain James Reeves, strongly backed by outgoing provincial commander Leonard Wood, decided to take the fight to the Jolo Moros. Though Scott’s plan had worked, many American officers disagreed with him, seeing the slightest Moro “provocation” as a threat to American rule.

Reeves sent out alarmist reports about a bloodless attack on and burglary at a U.S. rifle range. Wood, who had decided to extend his tour of duty in Moroland to oversee the battle to come, concluded that the Bud Dajo Moros would “probably have to be exterminated.” He then sent deceptive reports, ignored a recent directive from Secretary of War Taft forbidding large-scale military operations without his express approval, and issued secret orders for an impending attack.

As word reached the Moros through their excellent intelligence network, significant numbers of them promptly returned to the volcano’s rim. By March 5, 1906, Wood’s large force of regulars had the mountain surrounded and he promptly ordered a three-pronged frontal assault. The Moros, many armed with only blades or rocks, put up a tough fight, but in the end a massacre ensued. Wood eventually lined the rim of Bud Dajo with machine guns, artillery, and hundreds of riflemen, and proceeded to rain indiscriminate fire on the Moros, perhaps 1,000 of whom were killed. When the smoke cleared, all but six defenders were dead, a 99 percent casualty rate.

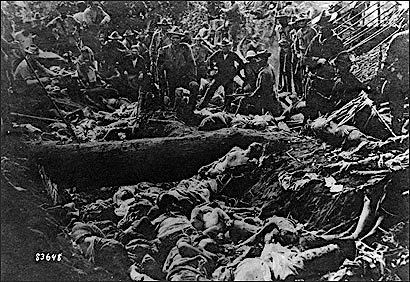

U.S. soldiers pose with Filipino Moro dead after the first battle of Bud Dajo, March 7, 1906, Jolo, Philippines. (Wikimedia Commons)

Wood, unfazed by the sight of Moro bodies, stacked five deep in some places, was pleased with his “victory.” His official report noted only that “all the defenders were killed.” Some of his troopers proudly posed for a photograph standing above the dead, including hundreds of women and children, as though they were big game trophies from a safari hunt. The infamous photo would fly around the world in an early 20th-century version of “going viral,” as the anti-imperialist press went crazy and Wood faced a scandal. Even some of his fellow officers were horrified. Pershing wrote his wife: “I would not want to have that on my conscience for the fame of Napoleon.”

The massacre would eventually even embarrass a president. Before the scandal broke in the press, Theodore Roosevelt had sent Wood a congratulatory letter, praising “the brilliant feat of arms wherein you and they so well upheld the honor of the American flag.” He’d soon regret it.

Mark Twain, a leading literary spokesman for the anti-imperialists, even suggested that Old Glory be replaced by a pirate skull-and-crossbones flag. Privately, he wrote, “We abolished them utterly, leaving not even a baby alive to cry for its dead mother.” The photograph also galvanized African-American civil rights activists. W.E.B. Du Bois declared the crater image to be “the most illuminating I’ve ever seen” and considered displaying it on his classroom wall “to impress upon the students what wars and especially wars of conquest really mean.”

The true tragedy of the Bud Dajo massacre — a microcosm of the Moro War — was that the “battle” was so unnecessary, as were the mindless assaults on empty, booby-trapped Afghan villages that my own troop undertook in Afghanistan in 2011-2012, or the random insertion of other American units into indefensible outposts in mountain valleys in that country’s far northeast, which resulted, infamously, in disaster when the Taliban nearly overran Combat Outpost Keating in 2009.

On Jolo Island, a century earlier, Hugh Scott had crafted a bloodless formula that might, one day, have ended the war (and American occupation) there. However, the careerism of a subordinate and the simplistic philosophy of his superior, General Wood, demonstrated the inherent limitations of “enlightened” officership to alter the course of such aimless, ill-advised wars.

The scandal dominated American newspapers for about a month until a sensational new story broke: a terrible earthquake and fire had destroyed San Francisco on April 18, 1906. In those months before the massacre was forgotten, some press reports were astute indeed. On March 15, 1906, for instance, an editorial in the Nation — in words that might be applied verbatim to today’s endless wars — asked “if there is any definite policy being pursued in regard to the Moros… There seems to be merely an aimless drifting along, with occasional bloody successes… But the fighting keeps up steadily and no one can discover that we are making any progress.” This conclusion well summarized the futility and hopeless inertia of the war in the southern Philippines. Nonetheless, then (and now, as the Washington Post has demonstrated only recently), the generals and senior U.S. officials did their best to repackage stalemate as success.

U.S. Army Gen. Martin E. Dempsey, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, receives a mountaintop briefing from American and Afghan Special Forces on Camp Moorehead, Afghanistan, April 23, 2012. (DoD photo by D. Myles Cullen)

The Illusion of ‘Progress’ in Moroland

As in Vietnam and later Afghanistan, the generals leading the Moro War perennially assured the public that progress was being made, that victory was imminent. All that was needed was yet more time. And in Moroland, as until recently in the never-ending Afghan War, politicians and citizens alike swallowed the optimistic yarns of those generals, in part because the conflicts took place so far beyond the public eye.

Once the larger insurgency in the main Philippine islands fizzled out, most Americans lost interest in a remote theater of war so many thousands of miles away. Returning Moro War veterans (like their war on terror counterparts) were mostly ignored. Many in the U.S. didn’t even realize that combat continued in the Philippines.

One vet wrote of his reception at home that, “instead of glad hands, people stare at a khaki-clad man as though he had escaped from the zoo.” The relatively low (American) casualties in the war contributed to public apathy. In the years 1909 and 1910, just eight regular Army soldiers were killed, analogous to the mere 32 troopers killed in 2016-2017 in Afghanistan. This was just enough danger to make a tour of duty in Moroland, as in Afghanistan today, terrifying, but not enough to garner serious national attention or widespread war opposition.

In the style recently revealed by Craig Whitlock of the Post when it came to Afghanistan, five future Army chiefs of staff treated their civilian masters and the populace to a combination of outright lies, obfuscations, and rosy depictions of “progress.” Adna Chaffee, Leonard Wood, Hugh Scott, Tasker Bliss, and John Pershing — a virtual who’s who in the Army pantheon of that era — repeatedly assured Americans that the war on the Moros was turning a corner, that victory was within the military’s grasp.

David Petraeus, a two-star general during the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, with Lt. Gen. William S. Wallace.

It was never so. A hundred and six years after the “end” of America’s Moro War, the Post has once again highlighted how successive commanders and U.S. officials in our time have lied to the citizenry about an even longer war’s “progress.” In that sense, generals David Petraeus, Stanley McChrystal, Mark Milley, and so many others of this era share disturbing commonalities with generals Leonard Wood, Tasker Bliss and company.

As early as October 1904, Wood wrote that the “Moro question… is pretty well settled.” Then, Datu Ali, a rebel leader, became the subject of a two-year manhunt — not unlike the ones that finally killed al-Qaeda’s Osama bin Laden and ISIS’s Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. In June 1906, when Ali was finally caught and killed, Colliers magazine featured an article entitled “The End of Datu Ali: The Last Fight of the Moro War.”

After Bud Dajo, Tasker Bliss toned down Wood’s military operations and oversaw a comparatively quiet tour in Moroland, but even he argued against any troop withdrawals, predicting something akin to “generational war” as necessary to fully pacify the province. In 1906, he wrote that the Moros, as a “savage” and “Mohammedan” people “cannot be changed entirely in a few years and the American people must not expect results… such as other nations operating under similar conditions have taken a century or more to accomplish.”

As Pershing lamented in 1913, the 14th year of the war, “The Moros never seemed to learn from experience.” And the violence only continued after his departure, even if American troops took an ever more advisory role, while the Filipino army fought the ongoing rebellion.

The Moros, of course, continue to combat Manila-based troops to this very day, a true “generational struggle” for the ages.

Missing the Big Picture, Then & Now

The last major American-led battle on Jolo in 1913 proved a farcical repeat of Bud Dajo. When several hundred intransigent Moros climbed into another crater atop Bud Bagsak, Pershing, who’d criticized Wood’s earlier methods and was once again in command, tried to launch a more humane operation. He attempted to negotiate and organized a blockade that thinned the defenders’ ranks. Still, in the end, his troops would storm the mountain’s crest and kill some 200 to 300 men, women, and children, though generating little of the attention given to the earlier massacre because the vast majority of Pershing’s soldiers were Filipinos led by U.S. officers. The same shift toward indigenous soldiers in Afghanistan has lowered both (American) casualties and the U.S. profile in an equally failed war.

Though contemporary Army officers and later military historians claimed that the battle at Bud Bagsak broke the back of Moro resistance, that was hardly the case. What ultimately changed was not the violence itself, but who was doing the fighting. Filipinos now did almost all of the dying and U.S. troops slowly faded from the field.

For example, when total casualties are taken into account, 1913 was actually the bloodiest year of the Moro conflict, just as 2018 was the bloodiest of the Afghan War. Late in 1913, Pershing summed up his own uncertainty about the province’s future in his final official report: “It remains for us now to hold all that we have gained and to substitute for a government by force something more in keeping with the changed conditions. Just what form that will take has not been altogether determined.” It still hasn’t been determined, not in Moroland, not in Afghanistan, and nowhere, in truth, in America’s Greater Middle East conflicts of this century.

The Filipino government in Manila continues to wage war on rebellious Moros. To this day, two groups — the Islamist Abu Sayyaf and the separatist Moro Islamic Liberation Front — continue to contest central government control there. After the 9/11 attacks, the U.S. Army again intervened in Moroland, sending Special Forces teams to advise and assist Filipino military units. If few of the American Green Berets knew anything of their own country’s colonial history, the locals hadn’t forgotten.

In 2003, as U.S. forces landed at Jolo’s main port, they were greeted by a banner that read: “We Will Not Let History Repeat Itself! Yankee Back Off.” Jolo’s radio station played traditional ballads and one vocalist sang, “We heard the Americans are coming and we are getting ready. We are sharpening our swords to slaughter them when they come.”

More than a century after America’s ill-fated Moro campaign, its troops were back where they started, outsiders, once again resented by fiercely independent locals. One of the last survivors of the Moro War, Lieutenant (and later Air Corps General) Benny Foulois published his memoirs in 1968 at the height of the Vietnam insurgency. Perhaps with that conflict in mind, he reflected on the meaning of his own youthful war: “We found that a few hundred natives living off their land and fighting for it could tie down thousands of American troops… and provoke a segment of our population to take the view that what happens in the Far East is none of our business.”

How I wish that book had been assigned during my own tenure at West Point!

[Note: For more detailed information on the conflict in the southern Philippines, see “The Moro War” by James Arnold, the main source for much of the information in this piece.]

Danny Sjursen, a TomDispatch regular, is a retired U.S. Army major and former history instructor at West Point. He served tours with reconnaissance units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He has written a memoir of the Iraq War, “Ghost Riders of Baghdad: Soldiers, Civilians, and the Myth of the Surge.” He lives in Lawrence, Kansas. Follow him on Twitter at @SkepticalVet and check out his podcast “Fortress on a Hill,” co-hosted with fellow vet Chris ‘Henri’ Henriksen.

This article is from TomDispatch.com.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Make Your End-of-Year Donation Today.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will not be published. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments, which should not be longer than 300 words.

Great story but your statement:

“The Moros, of course, continue to combat Manila-based troops to this very day, a true “generational struggle” for the ages.”

links to a 2012 BBC report and then fails to mention or give any credit to the current President of the Philipines.

There is no place in this world for USA imperialist forces to be stationed, whatever their fake purpose is.

Great piece Danny. “When will they ever learn?”

Thank you for this detailed article. The comparison to current “War on Terror” is not only revealing, it’s devastatingly appropriate.

The only point that struck me as inaccurate is an expression “the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.”

The Soviets did not invade Afghanistan; they were invited int; they went in to support a friendly government against destabilizing forces promoted by foreign interests; the same scenario that we see now in Putin’s support for Syria…

Why is it, in discussions that touch on Iran, the 1953 coup is regularly left out of the picture–it all starts in 1979, which was, in fact, the ultimate result of the ’53 coup, and the welling up of Islamic fury. They learned, as North American [Turtle Island] Indian people had learned, that the White Man based in Washington, D.C. speaks with a forked tongue.

I have been thinking about this ever since I was a teen some 60 Years ago. How does the military do it? How do the police forces do it? How can they so effectively brainwash people to kill those of their own class? Police and military personnel will shoot and kill their own family members and relatives. How can the 1% convince the lower classes to commit slaughters to preserve their grip on the wealth of a society. What they teach the military must be akin to a religion. Do they have a secret bible? Do they teach about some unknown to the rest of us, God? Ho does the 1 percent convince police to turn their guns on working class people like themselves? I remember my younger brother entering the Canadian Army when he was still a teen. We grew up dirt poor in a poor neighbourhood. it was the only job he could find at the time. What surprised me was when he came home on his first leave and all he talked about was the evils of communism and socialism. So again my question was . How in hell did they do it? How were they able to convince a kid , that grew up so poor that he had to leave school after grade eight, that the rich were not only saints but were entitled to their wealth and that his sworn duty was to see that they never had to pay their fair share to society. That he had a sworn duty to preserve their special status and immunity to law over the 99%. What is so disheartening is the fact that armies and police the world over seem to have recieved the same brainwashing. So how do they do it?

Almost no westerners or EUrabians (deliberate capitalization of the second letter) understand Islam, which means that any policy decisions made at any governmental level will almost certainly be mistaken. And yes, if one decides to “deal” with an islamic population, one had better subscribe to either genocide or a 1000-plus-year occupation. The only other approach is almost as unthinkable as genocide to any civilized people, which is why the fascist regime in Beijing is carrying out what will almost certainly be the world’s only successful “resolution” to the “Muslim problem:” They are “re-educating” adults who misbehave, and taking their children away from them to be raised by non-Islamic parents. In a generation, the last pious Muslims will die of old age (if not re-education), and Islam will be a fading nightmare in China.

I spent the first five (almost six) decades of my life oblivious to the teachings of Islam. I knew that its adherents were warlike, but I read such passages from the Quran such as Surah Al-Baqarah (Surah 2) Ayah 256 (“There is no compulsion in religion …”), which led me to believe that it was simply an Abrahamic faith which had come along after Christianity and had made some mistakes (I have been a born-again Christian since 1988). When 9/11 occurred, I looked on line for the Quran and began to read it, but it didn’t make much sense, so I gave it up in frustration. When Mr. Bush the Younger invaded Iraq, I was convinced that good treatment of the Muslim population by the U.S. would cause them to like us, and perhaps even to adopt a republican (as in the form of government, not the U.S. political party) form of government. About twelve or thirteen years after 9/11, I stumbled upon http://www.inquiryIntoIslam.com (among other sites) and was skeptical of the claims that were being made, so I began my own research, including visiting Islamic websites to get their take on Islam. I was horrified to learn – right from the imam’s mouth – that all the claims being made about Islam by the sites I had found were true.

I won’t go into great detail, because I’m just a voice on the internet, and no thinking person would take a single person’s word for something this important. There are some things of which an investigator should be aware as he examines Islam, however, so I will list them here, and let the reader check them out before he checks anything else.

First is the fact that Islamic scripture is more than just the Quran. The Quran is the word of Allah as revealed to Muhammed, and is thus forever unchanging, and also unchangeable by Muslims. Allah doesn’t explain everything that makes a good Muslim in the Quran, however; instead, he says in Sura Al-Ahzab (33) Ayah 21, “Indeed in the Messenger of Allah (Muhammad) you have a good example to follow for him who hopes in (the Meeting with) Allah and the Last Day and remembers Allah much.” In order to explain Islam, the Ulema has books collecting brief stories about Muhammed and the first Muslims which explain how Muhammed handled things; in Sunni Islam (with about 90% to 95% of all Muslims) these are called the Kutub Alsittah (the six “authentic books” of collections of such stories). Without the Kutub Alsittah, there would be no definition of the number of times a Muslim must pray each day, or which direction to face, or how to pray, nor would there be five Pillars of Islam. The books of the Kutub Alsittah (and other such collections which are not so highly regarded), along with the sira, are sometimes called the Traditions of the Prophet, and they explain in detail (each book usually has thousands of ahadith, or stories, in them) how Muslims should live by explaining what Muhammed did; they are almost as revered as the Quran, and *do* form part of Islamic scripture. Finally, beginning with “Sirat Rasul Allah” (“The Story of the Apostle of Allah”), written by ibn Ishaq, and preserved only in recensions by ibn Hisham and al Tabari, there are the sira, which are collections of sahih (authentic) ahadith put into chronological order, thus forming biographies of Muhammed. Because Muslims quite literally diligently search for “What Would Muhammed Do?” and put the answers into practice, one can learn what a pious Muslim should do by looking at what Muhammed did.

Next is the concept of abrogation. This practice comes from Quran Surah Al-Baqarah Ayah 106, which states, “Whatever a Verse (revelation) do We abrogate or cause to be forgotten, We bring a better one or similar to it. Know you not that Allah is able to do all things?” At some point, somebody must have challenged Muhammed on a revelation from Allah. This is Allah’s answer, which is taken to mean by the Ulema (religious scholars and clergy) to mean that if two revelations conflict, the one revealed later is the one which Muslims should follow. Muhammed spent the first twelve or thirteen years of his “ministry” in Mecca; there he was essentially powerless, and needed the protection of relatives. After learning of an attempt on his life, he and his followers fled to Yathrib, which he renamed to Medina (meaning city of the prophet), where his revelations of Allah enabled him and his followers to become violent. Thus, revelations which came to Muhammed after he reached Yathrib often abrogate revelations received while he was in Mecca. Finally, the reason I was confused when I tried to read the Quran is that the revelations are *NOT* in chronological order, so there is no clue as to which ayah abrogates which.

As mentioned above, one need only look at Muhammed to learn about Islam. He owned slaves, took slaves, kept sex slaves (concubines, a nice word for sex slave), and gave and received slaves as gifts; he also called black people “raisin-heads,” and considered them suitable only for a life of slavery. He married a little girl when she was six, and consummated the “marriage” when she was nine. He allowed his followers to assassinate those who badmouthed him, including women. He ordered his followers to rob caravans to support his little band of Muslims, and they not only did the robberies, he also let them kill the guards after they had surrendered. He also led twenty-nine such attacks himself, fighting in nine of them, and dispatched his thugs many more times than that during his career as a “prophet.”

There are those who claim that everybody did what Muhammed did back in the seventh century. I have to agree, but also must point out that nobody who founded an existing religion did such things. Worse yet, Muhammed is considered al-Insan al-Kamil (the Perfect Man) and Uswa Hasana (the Model of Conduct for Muslims … males, anyway), so Muslims are *REQUIRED* to do as Muhammed did. And if we take Muhammed out of Islam, Islam disappears, because it is as much founded upon Muhammed as it is on his sock puppet, Allah.

In any case, there is no way that any military occupation can contain Islam, unless it also includes genocide or the Chinese approach to the Uighurs. The only other option is probably thousands of years of military occupation, and if the sex-and-death cult of Islam is allowed to survive, even that won’t be long enough. It is doubtful that *any* of the military or federal authorities of the U.S. besides the founders who fought the wars in Tripoli actually understood any part of Islam. Thus, I can confidently predict that U.S.policy regarding Islamic countries will continue to be flat-out wrong. Furthermore, since we’re busily importing *lots* of Muslim refugees (why isn’t Saudi Barbaria doing any of that?), I can also predict that we should have some dandy fighting going on right here at home, especially since Mr. Obama made sure that no federal employees are taught anything about Islam when learning about terrorism (Muhammed said, “I have been made victorious through terror.” (Sahih al-Bukhari 4.52.220; *all* of Imam Bukhari’s ahadith have been judged sahih by the Ulema)).

Again, check out Islam for yourself.

Very good, Mr. Sjursen. For your own information and edification, may I recommend “The Nightmare Years” by William L. Shirer? Shirer is probably best known today for his opus “The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich” but, in fact, he was a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune. While he was operating out of Germany by the end of the interwar years (he was one of the last correspondents to leave Germany before the war started) before that he had been following Gandhi in and around India. Whilst doing so, he met the man who was the King of Afghanistan (yes, the same guy who was deposed in 1978), was able to get into his entourage, and get into Afghanistan. The British were blockading Afghanistan at the time and nominally speaking they weren’t letting reporters into the country. The book contains a fair description of Afghanistan in the early 1930’s. I think you’ll recognize it.

Thank you Danny Sjursen. This is an excellent article that every member of Congress should read and every newspaper in the U.S. should print.

Far too many people in the U.S. are completely ignorant of the long history of futile and brutal savagery that their tax dollars have funded for well over 100 years and which continues to this day.

Thank you, CN, for featuring it here.

We have with the ‘all voluntary military’ the opportunity to end these endless US wars. Enough of that “thank you for your service” bs omitted from the mouths of people who have no idea what they are saying. Stop your friends from joining the military. Starve the war machine. It is now in our power to do so. Make them initiate a new draft. With that will come the 2nd Revolution!

No More War

You can sell more newspapers whipping up the fight and the idea of a win. It’s a terrible dynamic. No one wants to read about “ losing”. How many can win an election saying, “ Cut and run”, be it Philippines, Vietnam Nam, Iraq or Afghanistan. 55,000 deaths , 150,00o wounded of draftees allowed Congressmen/woman a chance to run anti war, but just leaving was not very popular: “ negotiated peace” was the misnomer. The sad truth seems to be that injury to a volunteer army of very few per cent of the population who do repeated tours does not raise much interest . Danny is a lonely voice save Bacevich and Graubard against which is $ 800 billion defense industry and a compliant media voice .

Actually, I think the volunteer military is a major element of the current situation that permits the Bosses and their lackeys to continue the endless series of military misadventures.

Americans are, for the most part, perfectly happy to let volunteers and faraway dark-skinned people do the suffering and dying. That’s why there hasn’t been an effective antiwar movement in the US since the draft ended.

Anyway, the technology of slaughter has greatly reduced the need for large numbers of troops, so it’s unlikely that the warmongers will have to face a serious shortage.

Smedley Darlington Butler, who eventually became a Major General in the US Marine Corps, gained much of his knowledge and experience of the savagery of war, while serving as a young officer in The Philippines. In the few biographies written about him, he described the war. After he retired, he wrote a 100 page tract entitled “War is a Racket” which is fought for capitalist exploitation. His efforts to get published ran into a blockade and book distribution was scarce because he was blacklisted. Americans were psychologically dumbed by the investment (moneyed) class. If one wanted a copy, it was mostly found in parts of Europe. Butler, during his long career, was the most decorated Marine, including several severe wounds. He was a close friend of a classmate at the Naval Academy, James Lejeune, who became Marine Commandant even though he was outranked by the colorful but controversial Butler who rarely played things safe with Navy brass.

A very informative column. What it omits is that the US Army’s slaughter of Filipinos was part of the American desire to gratify the businessmen and corporations that saw the Philippines as a base for the commercial invasion of China with its ‘vast population of potential consumers.” The guiltiest villains were the ones in Washington, presidents and members of Congress, who condoned the killing of hundreds of thousands, Moros and others, in the islands. American greed knows no bounds.

Thanks to Danny Sjursen. It is true that this history has been ignored or sanitised for a century, and its parallels with this century are powerful.

“We found that a few hundred natives living off their land and fighting for it could tie down thousands of American troops… and provoke a segment of our population to take the view that what happens in the Far East is none of our business.”

If only these few words could be taken to heart by US policy-makers and military leaders, perhaps the spending on “defense” could be confined to real defense and not terrible wasteful aggression and destruction.

Truth seems to be in the pudding! It must be true . America’s military after 38 years had learned nothing from Vietnam.

The number one reason this occurs is because no one was held accountable for the tragedy in Vietnam.

Now we see the same ole’ same ole’ with American troops over extended, scattered far and wide and around the globe and pahing the price for the ignorance of the leadership.

Give them hell Danny!

So already way back when the US was sticking it’s nose where it didn’t belong. A “nose” that just keeps growing and growing…

As a youth, my Grandfather called me a little man, I was priveledged to be able to tag along with him into local, they were called saloons, and other Civic groups, VFW, Legion and Fraternal lodges, and no one dared say he could not have me with him and that is my “Boniides” as to what I witnessed.

I witnessed men who had fought in every war from Spanish American through Korea, who when after closing hours and women if allowed in, and general populace had gone home, when in their cups they could and always seemed to end in conversations of war experiences; I listened, poured beer, lit pipes cigarettes and cigars, and never spoke unless spoken to first.

Gramps older brother had fought in Phillipines from initial invasion and through Moro campaigns and he along with 3 or r shirtail relatives spoke openly of what they did, as did thosebfrom Gramps WEI through Korea.

Gramps had two rules, one about speaking of who and what I heard and never talk war when women were present, they were to scatter brain dumb to understand.

Truth talk was easy through generations of men who in those days volunteered as local or State units and mostly remained that way during war until their friends and relatives were killed or so badly wounded they became replaced by strangers, so it was easy free talk in small rural counties and towns with relatives or friends of generations.

Gramps uncle returned from Phillipines as a broken man in body, Maleria almost killed him more times than 3 bullet wounds from Fillipine nationalist and a Moros, machete,not a f’n knife.

But it was in mind that hurt the most, as he told of slaughtering unarmed Nationalist prisoners on a btidge until his 30/40 Irags barrel turned red and action swelled to become inoperative.

Then when he and others Phillipine Campainers told of massacreing women children old men and women who fought bravely until forced to surrender, sometimes their voices broke and from so.ewhere came flask with stronger than beer being poured for them.

Almost too a man those local men had read Smedly Butlers book and agreed with him.

Hopefully somewhere in familys clan attic resides a book written with pictures about the Spanish American War with notations written by him challenging the “Official Glory lies.

It had poems he and other men had written, songs they had among and list of men’s names he noted had not come home or had but in pieces.

I side were a couple letters from men there, entrusted to him to mail if they died, all with notices of non able to deliver or wrong addresses.

I read that book multiple times, memorized his and others writings, his notations and both letters he had mailed to Gramps and their mother and the undeliverable as well,

They tell truth right out of the horses mouths as We used to say,annd not out of Generals, politions, and educated gentry tales of Flags Glory written by horses asses who were not firing rifles that glowed red.

US reinforced one of most moraly corrupt leadership’s in world, turned vast areas of major cities into houses of prostitution and vice pleasure places, lermanently impoverishing Moro decendents along with millions of rural peasantry, until finally the Phillipine people first threw out Marcos and US military.

Here is gist of my criticism, those who write of that time, where did they get info upon subject, surely not from those who had been there, or lived during those eras, for until after Vietnam era only tales were of Generals great glory and battles they won while waving old glory, and reinforced their glory by mentioning a few lower ranks medals to improve own images.

T he masses of men’s stories untold, except where men once gathered, in their cups , United bya history that no woman or child must hear, not bragging as our troop do today of numbers of kills, bombs dropped, and cannons fired to impress the hero worshipper culture.

Did that listening turn me into antiwar, he’ll no, I volunteered for Vietnam, saw and found the truths they had spoke, and then turned to repeating their truths and my own to another generation.

Will history learned stop others from going to war, and ionizing into national heros andbsaints, hell no.

For as one famous personage asked a group of young men setting out for Boer War in Africa and India why they were going,

The answer he got was” Because our father’s did”!

HB – unfortunately, you make one of the key, seldom-emphasized points regarding excellent anti-war articles like this, or Smedly Butler’s book, or numerous other ones I’ve read when you close with: ”..why they were going,

The answer he got was ‘Because our father’s did’!”. I perceive that this, along with a ‘pre-disposition’ among too many (not ‘ALL’, but ‘too-many’) men towards aggression/violence especially in ‘tribal’ situations, perpetuates militarism and imperialism across many cultures and eras. Strong, straight-forward anti-war writings and media ARE around and have been around for 100’s of years (though they’re often drowned-out by nationalistic voices) but they seldom seem to gain long-term traction because of these things and people’s short memories.

Thank you Danny Sjursen. I’m reminded of a scene on a special features section of a DVD where LT. General Harold G. Moore Jr. is describing to General Westmorland and Robert McNamera his experience in the Ia Drang Valley. They seemed to dismiss his broader message that, in essence, this was not the scenario that they “gamed” for, a tragic mistake that all armies of Empire make. At any rate, many thanks.