Arnold R. Isaacs reports on a symposium hosted by the U.S. Special Operations Command on a subject that remains controversial within the military, but is gaining recognition.

A destroyed part of Raqqa, Syria. (VOA/Mahmoud Bali, Wikimedia Commons)

By Arnold R. Isaacs

TomDispatch.com

When an announcement of a “Moral Injury Symposium” turned up in my email, I was a bit startled to see that it came from the U.S. Special Operations Command. That was a surprise because many military professionals have strongly resisted the term “moral injury” and rejected the suggestion that soldiers fighting America’s wars could experience moral conflict or feel morally damaged by their service.

Moral injury is not a recognized psychiatric diagnosis. It’s not on the Veterans Administration’s list of service-related disabilities. Yet in the decade since the concept began to take root among mental health specialists and others concerned with the emotional lives of active-duty soldiers and military veterans, it has come to be fairly widely regarded as “the signature wound of today’s wars,” as the editors of “War and Moral Injury: A Reader,” a remarkable anthology of contemporary and past writings on the subject, have noted.

For those not familiar with the tag, moral injury is related to but not the same as post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, which is a recognized clinical condition. Both involve some of the same symptoms, including depression, insomnia, nightmares and self-medication via alcohol or drugs, but they arise from different circumstances. PTSD symptoms are a psychological reaction to an experience of life-threatening physical danger or harm. Moral injury is the lasting mental and emotional result of an assault on the conscience — a memory, as one early formulation put it, of “perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”

For those not familiar with the tag, moral injury is related to but not the same as post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, which is a recognized clinical condition. Both involve some of the same symptoms, including depression, insomnia, nightmares and self-medication via alcohol or drugs, but they arise from different circumstances. PTSD symptoms are a psychological reaction to an experience of life-threatening physical danger or harm. Moral injury is the lasting mental and emotional result of an assault on the conscience — a memory, as one early formulation put it, of “perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations.”

The idea remains controversial in the military world, but the wars that Americans have fought since 2001 — involving a very different experience of war fighting from that of past generations — have made it increasingly difficult for military culture to cling to its old manhood and warrior myths. Many in that military have had to recognize the invisible wounds of moral conflict that soldiers have brought home with them from those battlefields.

That shift was evident at the moral injury symposium, held in early August in a Washington, D.C., hotel. The feelings and experiences I heard about there were not necessarily representative of the climate in the wider military community. The special operations forces, which put on the event, have their own distinctive character, culture and experiences, and a disproportionate number of the 130 or so attendees were mental-health specialists or chaplains, the two groups that have been most open and attuned to the very idea of moral injury. (A military chaplain in the Special Operations Command, in fact, first had the idea for the symposium.)

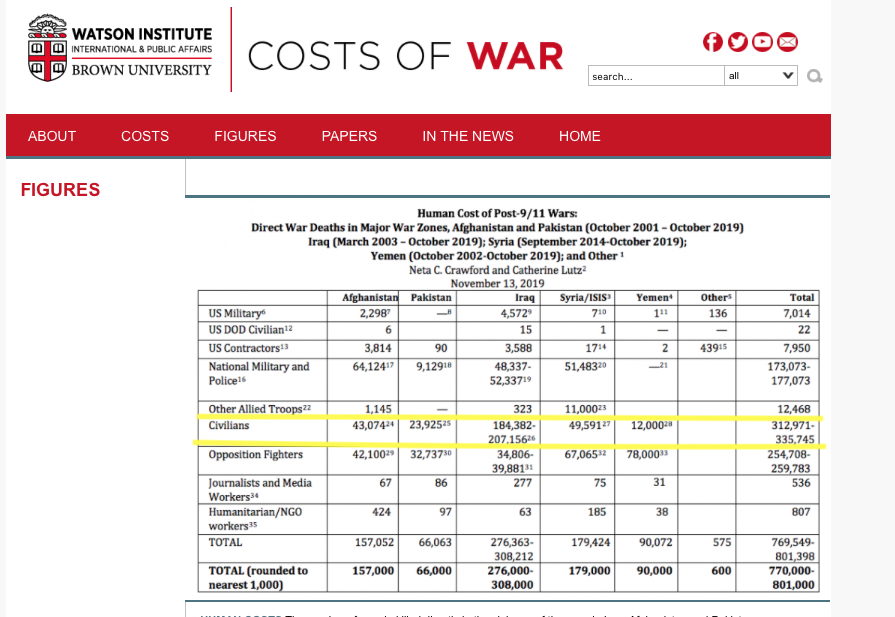

Still, the symposium emerged from the same history the rest of the military has lived through: 18 years of uninterrupted violence, of war without end in distant lands, that has killed or wounded some 60,000 Americans and a far greater number of foreign civilians, while displacing millions more and helping drive the worldwide refugee population to successive record-setting levels. Against that backdrop, those two days in Washington proved gripping and thought provoking in their own right. What follows are some of the thoughts they provoked in my mind as I listened or when I later reflected on what I heard.

Something Said, Something Unsaid

In the sessions I attended, virtually every speaker mentioned one relevant fact about our present wars and the soldiers who fight them. But a different relevant fact on the same subject was almost completely missing.

Again and again, participants spoke about the great change in how soldiers experience war. In past generations, for the great majority of service members, war was a one-time event. In the 18 years since 9/11 and the invasion of Afghanistan, war has become a permanent part of soldiers’ lives in a continuing cycle of repeated deployments to battle zones. (And that’s not to mention the even more startling change for those who see combat remotely, sitting in front of screens and firing missiles or dropping bombs from unmanned aircraft flying over targets thousands of miles away.) As nearly all the symposium speakers pointed out, that change in the war-fighting experience has also changed the nature of combat trauma and the military culture’s understanding of and attitudes toward it.

Here’s the reality that almost nobody mentioned, though it’s closely related: the reason these wars have lasted this long and have become a permanent part of soldiers’ lives is that they have not been successful. My notes record only one presentation where that connection was even touched upon, and then only implicitly, not directly.

That single indirect mention came in a discussion group conducted by Air Force Lieutenant Colonel David Blair, the commanding officer of a Florida-based remotely piloted aircraft squadron. He mentioned that his MQ-9 Reaper drone crews increasingly have come to prefer missions in theaters other than Afghanistan. Specifically, he said, they were most positive about strikes against ISIS in Iraq and Syria where they “could see the front lines moving.” (That suggests he was referring mainly to the 2016-2017 period when those Reapers were supporting American and Iraqi ground forces recapturing territory that had been under ISIS occupation.) Those missions led to “less trauma” for his operators, he said. At another point, he added that “if it [an engagement] ends well, they look back on their lives differently.”

Drone operators launch an MQ-1 Predator unmanned aerial vehicle for a raid in the Middle East. (DoD)

Other than that single remark about his crews preferring missions in other theaters, Blair never made any explicit comparison between Afghanistan and any other conflict zone. However, what he did say sounds like plain common sense. It’s logical that when a military operation is relatively successful, it’s easier for soldiers to explain to themselves and live with their own actions. It must help mitigate moral injury symptoms, at the very least, if they can tell themselves that a greater good was accomplished.

Conversely, if you did something that leaves you with doubt or regret but achieved no positive results, that would lead to more painful feelings and less defense against them. So, in one way, it seems odd that, except in those few moments, I didn’t hear anyone make the connection between the lack of victory in America’s wars and the incidence of trauma.

On the other hand, it’s not so surprising that such connections were not made more often or more clearly. They would only have reminded the participants of an uncomfortable reality: that America’s wars in the present era have, on the whole, fallen far short of producing any greater good that would help justify the moral injury so many soldiers are struggling with, not to mention all the other human damage those wars have caused.

I can’t know their inner feelings, but I can guess that it would have been painful for many symposium participants to admit that fact out loud or to let themselves think it at all. Probably it wasn’t something the organizers would have liked to hear either or remember when they face troubled soldiers in the months and years to come.

Moral Clarity Versus Moral Injury

Another moment in that same session suggested a different but related link between the nature and circumstances of a military operation and the likelihood of trauma. This one had to do with the moral perception of the operation itself.

Since his crews are not physically at risk when carrying out their missions, Lieutenant Colonel Blair pointed out, the traditional “kill or be killed” formula of the battlefield can’t help them explain their war to themselves. Instead, the drone fighter’s explanation has to be “kill or someone else will be killed.” In turn, that determines not just what they do, but who they feel they are. “Being a protector of others,” Blair said, becomes their “core identity.”

A couple of quotes in a December 2017 article on an Air Force website show how the missions against ISIS strongly validated that identity — and, indirectly, suggest why operations in other theaters have not.

The article, which I found after the symposium ended, was a feature about a remotely piloted aircraft unit (not Blair’s) that supported the ground operation to recapture Raqqa, the Syrian provincial city that ISIS designated as the capital of its so-called caliphate. One quote is from a squadron commander: “It wasn’t our aircrew just striking ISIS targets. We also were safeguarding and watching over [friendly Syrian troops] as they cleared civilians moving out of the city to safe locations.” The article also quoted a sensor operator: “My favorite part of this job is that I’m able to help civilians be safe and I’m able to help liberate whatever city we need to. There’s no better feeling than knowing you can directly impact the battlefield and other people’s lives.”

Obviously, when their screens showed them the civilians they were helping, and not just the enemies they were killing, those crewmen found moral clarity, rather than moral conflict, in their experience. From Blair’s comments, one can surmise that was true for his crews as well, presumably for similar reasons.

Sadly, it is also pretty obvious that such a sense of clarity has been the exception, not the rule, in the wars Americans have been fighting for nearly two decades. That doesn’t automatically mean those wars were not moral, but whatever their moral nature, it would only rarely have shown up on the drone operators’ screens — or in the sightlines of soldiers looking at actual battlegrounds in real space — as clearly as it did for those airmen remembering their Raqqa missions. (Not that Raqqa raised no moral questions at all. Yes, the fighting there liberated its inhabitants from an exceptionally brutal occupation. But it also destroyed most of their homes, largely in air strikes by U.S. and allied planes that, by one estimate, dropped 20,000 bombs on the city. By the time the campaign was over, Raqqa, like a number of other Syrian and Iraqi cities, was in almost complete ruins.)

President Barack Obama speaks to soldiers who were among first to deploy to Afghanistan, Fort Drum, N.Y., June 23, 2011, after announcing announcing a drawdown of troops in a TV address to the nation. (U.S. Army/Steve Ghiringhelli)

A Question, Maybe Farfetched…

I didn’t frame it this way when I was at the symposium, but this question later came to mind: Has the U.S. military as an institution, not just its individual service members, morally injured itself over the last 18 years?

This is a military force that never stops declaring it’s the best and strongest in the world, but has not successfully concluded a significant war for nearly 30 years or maybe longer. (The first Gulf War of 1990-1991 looked like a great win at the time, but appears like anything but an unequivocally positive accomplishment in retrospect.) It may sound farfetched, but is it unreasonable to wonder if that dissonance, that wide gap between goals and actual accomplishments, might leave a collective sense of sorrow, grief, regret, shame, and alienation? That’s the list of feelings that Glenn Orris, a Navy chaplain, displayed on a chart in his symposium presentation and specified as the ones that keep morally injured service members awake at night.

I’m posing this as a question, not offering it as an answer. Certainly, at various moments during the symposium, I had a sense not just of individual but of collective trauma. As an outsider in that world, I can’t and won’t venture to evaluate the emotional state of the military as a whole. Still, the question doesn’t seem ridiculous.

A New Idea of What Moral Injury Really Is

The final event of the second day — an unusual closer for a professional or academic conference — was a reading of Sophocles’ play “Ajax,” as rewritten by Bryan Doerries. After the reading, Doerries, artistic director for Theater of War, the company that put on the performance, moderated a discussion with a panel of four recent veterans and members of the audience.

Essentially, he attempted to draw out the panelists and the audience on what the play was trying to say and how that 2,500-year-old story of a warrior’s depression, madness and suicide might connect to their own experience. Listening to various responses, I found myself thinking that perhaps the main purpose of his, if not Sophocles’s, version was to make the audience think about what war is. What it really is, not the heroic myth humans have made of it from ancient times on. And then I thought, maybe that’s what we’d been talking about for the previous two days. Maybe that’s what moral injury is: realizing the true nature of war.

Along with that thought came another, one that first occurred to me nearly 45 years ago when, as a reporter for The Baltimore Sun, I personally witnessed the disastrous end of the Vietnam War. I’ve believed ever since that covering war from the losing side gave me a truer knowledge of its nature than I’d have gotten from that or any other war’s winning side. Maybe I should say darker, not truer, since I suppose the winner’s war is real, too. But whichever word you choose, my experience, I felt, gave me a more unobstructed view of war. I could see it more clearly for what it was precisely because there was no good result to balance against the death and loss and terror and despair. There was no excuse to explain away the human disaster I’d seen and written about for several years, no way to tell myself that the war was necessary or had served any purpose.

That bit of personal history makes me think it’s not accidental that our present consciousness of moral injury has come out of wars we didn’t win. They haven’t been lost in the same clear-cut way that the war in Vietnam was. They haven’t (yet) ended in the kind of catastrophically decisive final act I witnessed there in the spring of 1975 in the weeks that led to Saigon’s surrender. But these recent wars haven’t accomplished their goals either, or given our soldiers a worthwhile reason for what they’ve gone through, which is surely a key piece of the moral injury story.

I was a civilian journalist, not a soldier. I went to Vietnam to report, not to fight. I didn’t come home with any trauma symptoms. But I have all the feelings that Chaplain Orris listed as identifying markers for moral injury: sorrow, grief, regret, shame and alienation. Those emotions come from what I learned about war, not from anything I did, and that makes me believe it may not be wrong to think that what we call moral injury might not be just one person’s response to particularly troubling events, but a symptom of something larger, of seeing war individually and collectively for what it truly is.

A Last Thought

In closing, I will turn back to the editors of “War and Moral Injury.” In their introduction, Douglas Pryer, a retired army intelligence officer and Afghanistan and Iraq veteran, and Robert Emmett Meagher, a classicist and professor of humanities at Hampshire College, pointed to an aspect of war that is missing in their anthology, the symposium, and in American culture more broadly:

“We must acknowledge a great gap in this text as in nearly every other on the subject of America’s wars and veterans: the deaths and wounds, physical and spiritual, inflicted on the ‘others,’ our enemies, especially our ‘civilian enemies.'”

Pryer and Meagher are right. Such an acknowledgement is almost entirely absent from the national discourse about our wars and their legacy. But without it, no moral wound, whether an individual’s or a society’s, can truly be healed.

Arnold R. Isaacs, a journalist and TomDispatch regular based in Maryland, covered the final years of the Vietnam War for The Baltimore Sun. He is the author of “Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia, Vietnam Shadows: The War, Its Ghosts, and Its Legacy,” and an online report, “From Troubled Lands: Listening to Pakistani and Afghan Americans in post-9/11 America.” His website is www.arnoldisaacs.net

This article is from TomDispatch.com.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Before commenting please read Robert Parry’s Comment Policy. Allegations unsupported by facts, gross or misleading factual errors and ad hominem attacks, and abusive or rude language toward other commenters or our writers will not be published. If your comment does not immediately appear, please be patient as it is manually reviewed. For security reasons, please refrain from inserting links in your comments, which should not be longer than 300 words.

A reminder that many young “men” and “women” in the military are TEENAGERS and early 20’s. Neuroscience tells us that human brains are not even fully developed until the mid 20’s. I think of how naive I was at that age… and they buy into the propaganda about “honor,” “service,” and “bravery.” Life is a tough teacher when the experience does not play out like the recruiter pamphlets and Hollywood movies. I think the rank and file deserve a little compassion. Its the Top Brass, Politicians, and MIC that deserve a special place in Hell for serving up kids for the war machine… and wreaking civil societies the world over.

Just a side effect to make this country the most powerful in the world. To the individual this is wrong, to the powerful this does not matter. Whatever it takes is Americas model

A good article which considers morality as it confronts our military people and their morale and its effect on their morale.

“It’s logical that when a military operation is relatively successful, it’s easier for soldiers to explain to themselves and live with their own actions. It must help mitigate moral injury symptoms, at the very least, if they can tell themselves that a greater good was accomplished.”

It does not morph into the broader question of morality, which goes to the wars our soldiers who fight, even the way we fight them. The statement above suggest that the right or wrong of the war is beyond the concern of the Special Operations Command. One must assume special operations is focused on how to retain or upgrade morale, to serve our elected leaders in light of the immorality of our regime change wars.

Robert Emmett’s Meagher’s words:

“We must acknowledge a great gap in this text as in nearly every other on the subject of America’s wars and veterans: the deaths and wounds, physical and spiritual, inflicted on the ‘others,’ our enemies, especially our ‘civilian enemies.’”

We must also acknowledge that the morality of our elected leaders, the statesmen , bureaucrats and their generals corrupts America.

And we must also include our mind shaping media pundits.Who can forget the sound and light show which kicked off the Iraqi War and the comment of our still working pundits that “we are all neocons now”.

I can’t imagine a better article calling for a “Truth And Reconciliation Commission”.

Several years ago while traveling in Nevada I passed a sign near the Navy’s training facility near Hawthorn. It read “Welcome to the miracle mile celebrating those who served in WWII,” then another saying “Welcome to the miracle mile celebrating those who seved in The Korean Conflict,” then “Welcome to the miracle mile celebrating those who served in Vietnam,” and finally, “Welcome to the miracle mile celebrating those who served in GWOT,” …GWOT? Yes GWOT!, “The Global War On Terrorism” the height of absurdity…

Another aspect that may lead to “moral injury” is when the soldier finally realizes the underlying reason he is at war in the first place. It is not to “get the bad guys”; it is to control foreign nations and their natural resources. It is to serve Empire. The Syrian army is fighting to oust foreign terrorists like ISIS, and to restore order in a secular Arab nation that has several religious groups within it. They don’t want or need our help. We have not been invited. The Syrian people do not appreciate us destroying a village in order to “save” it.

As for victory, the way the author implies its meaning is not the only real goal, at least not in Syria. Arabs killing Arabs, continuing chaos, and the endless expending and replenishment of armaments is a victory of sorts. History has shown us that sovereign nationalist secular governments will not be tolerated. They must be subservient to Empire, or else face a never ending onslaught on many fronts, both military and economic.

Thanks for raising the issue of morality and pointing out the elephant in the room. It is pretty thick for a country (and its institutions) to talk about morality and its “injury” when they have been committing illegal wars, torture and war crimes with impunity since I don’t know how many decades.

“Moral injury” to people who chose to join the US military might well rank as perhaps the most ironic and well-deserved consequences of warfare in all history. There’s no draft. Men and women who make their careers in destroying entire societies so that white Americans can enjoy burning fossil fuels at a lower price to them should not be regarded as victims of war. Victims of their own perfidies, maybe. The author appears to regard the comfort of so-called soldiers to be of greater importance than that of the people they kill and maim.

I would be surprised if most who have been to war don’t have moral injuries. Wars are simply a tool for the rich to get richer and are absolutely amoral. War = sanctioned murder…

So, Mr Isaacs, you would seem to be positing that no matter what we in the west do to other countries via invasion, bombing, napalming, Agent Oranging – over many years, with millions of deaths and the devastations to their lives, of those “other peoples,” on our docket – so long as *we* win, our military personnel ought NOT to feel *any* pricking of their consciences? That “winning” obliterates all ethical, moral concerns, let alone likely criminality in beginning the war, invasion (whichever one it was/is) in the first place? That military personnel do NOT, in fact, have the escape via “I was just following orders” when I blew up that vehicle holding a family – “they looked like terrorists to me.” Illegal orders are illegal orders and are against international law.

And might I ask – what about the civilian populations who have had to endure the US-UK-FR/NATO’s bombardments, devastation of their infrastructure, their economies? Their deaths are far more numerous than those of the invading, unwanted western militaries, and their PTSD far more serious and long-lasting, especially that inflicted upon children. But hey – the PTSD, moral injury that the US military have to deal with, including that of those “Turkey shooters” and their even more ethically challenged military “descendants” in Nevada, those who are “playing” video games of death destruction to really existing people, most of whom are actually not combatants at all.

Frankly, as a pacifist I have little to no sympathy for present day military personnel – they *choose* to be members of an imperial killing machine, of an imperial slaughter policy to be visited on any and all peoples who do *not* crawl before US dictated dominance. There is no way any one of these wars – since WWII – can be posited as in any way other than amoral, unethical, illegal and all about US corporate-capitalist-imperialist hegemony .

AnneR-

As much as I agree with you, I do have compassion for the children who volunteer to be America’s war machine killers. They have been duped their entire lives. They are playing “Cowboys and Indians.” The ones who actually wind up “on the ground” soon realize that war is nothing like what they’ve been told; but by then it is too late, and they are fighting for their own survival. Moral injury and PTSD is inevitable, and their lives from that point on will be plagued by images of the horrors they endured and inflicted upon others. The evil ones are the puppet masters who manufacture the charade of “fighting for freedom and democracy” that they fell for.

Skip Scott, as usual, has it right. The children who volunteer to go into the military are just kids… undeveloped, green, idealistic kiddos. And that’s the way the military likes them- impressionable, gullible, malleable kids. Because that is what children are! And I do have great sympathy for those souls, whether they be blinded by a sense of duty to country, or be they legacies of their fathers, mothers, or grandfathers and grandmothers who “served their country.” They can hardly escape this crap indoctrination. The recruiters have them by the short hairs in high schools around the country, telling them lies and propaganda that entrenches those lies in their developing minds, especially vulnerable if they are poor. I have sympathy. And empathy. These are ALL our children. We must teach them different ways of being- all of us must try to teach them differently. That is what makes a humane, well-developed, empathetic human be born into adulthood. Good post, Skip Scott.

For many international readers, this well written article may have a taste of bitterness or even irrelevance (from the perspective of the victim). To date there has been little or no ‘moral injury’ detected with the political instigators and perpetrators of decades of american exceptionalism, wars and violence in every area of the world. Within 2019, interference in Latin America, the Middle East, Asia has been overwhelming. Moral injury need not be limited to military operatives, these wars are fought on behalf of a nation. The complexity of moral injury in post-war Germany can show us the very long path I am confident this nation has not found the entrance to yet.

Hmm. Disturbing but probably not for the reason that one might imagine.

“many military professionals have strongly resisted” There’s another name for a military professional – mercenary. Or, maybe I should say, professional military person. They really have to be amoral and are closer to a mob hit man than a normal person. So I’ll just bet they resisted. The recognition that some of their number aren’t simply killing machines would be bad. Certainly for morale.

“the missions against ISIS strongly validated that identity” Really? Then they were fooling themselves. This has to be part of the Stockholm syndrome. Understand that when the author was having his Christ consciousness moment in ’75, I was just exiting the USAF after completing my (coerced) term of service. Yes, ISIS is/was a totally evil organization and there were people who desperately needed protection from them but…. the US created ISIS by virtue of the stupid things we have been doing in the Middle East but specifically once we perpetrated aggressive war on Iraq. I would think that the better solution is to not create the problem in the first place. That needs to be repeated over and over again. The American public and their politicians have the memory span of a mayfly in late August.

“I’ve believed ever since that covering war from the losing side gave me a truer knowledge of its nature” Bullshit. The US lost some 55,000 troops and the other countries like Korea and Australia lost troops as well who were there to prevent the Vietnam war from being blatant American aggression, but those total numbers pale by comparison to the million or so Vietnamese who died as a direct result of “allied” military action. And that doesn’t count the number of Vietnamese who continue to suffer and die from left over UXBs but also from the results of our use of Weapons of Mass Destruction. If chemical weapons are WMDs for Assad, Agent Orange is one for us. Only we really did use WMDs. The US was defeated by the Vietnamese but we weren’t the ones who did the suffering.

Your closing paragraph is the truest in your piece. We never acknowledge the horrors we inflict on other, generally totally innocent, civilian populations.