The police officer who killed Michael Brown convinced a St. Louis grand jury not to indict by likening the unarmed 18-year-old black man to “a demon” who looked “mad that I’m shooting at him” language reminiscent of an earlier era when whites saw blacks as frightening sub-humans, writes William Loren Katz.

By William Loren Katz

The murder of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, illustrates that even when an offending officer is brought before a grand jury, he can explain away why he fired shot after shot at an unarmed suspect — and have jurors wave him home unpunished, perhaps a hero.

The death of Eric Garner in New York shows that a police officer can commit murder using a banned chokehold in broad daylight while being videotaped by a bystander and still avoid indictment. [Remember the similar situation surrounding Rodney King’s beating in Los Angeles?]

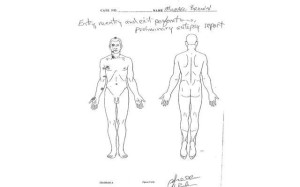

The autopsy drawing of Michael Brown’s body after the 18-year-o;d was gunned down by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

In both instances, the police also left their victims on the street, Brown lying dead for four hours and Garner for precious minutes when swift medical treatment might have saved him. In their behavior, the police were twice giving a negative answer to the question: “Do black lives matter?”

Since nothing exists in the DNA of white police officers or other white people that leads to race-driven murder, the motivation of these armed guardians of the law lies elsewhere. The only available testimony today is from Officer Darren Wilson before the St. Louis County Grand Jury as he threw useful light on how he saw his deadly confrontation with Michael Brown.

Both Brown and Wilson were over six feet tall and over 200 pounds. But Wilson who was armed compared himself to “a five-year-old holding onto Hulk Hogan.” To him the unarmed suspect “looks like a demon, that’s how angry he looked.” Further he “was almost bulking up to run through the shots, like it was making him mad that I’m shooting at him.”

Wilson’s words rang bells in my historian’s mind; it took me back to 1900 when the American Book And Bible House of St. Louis published a popular justification of lynching entitled The Negro A Beast. This was during the long reign of “Judge Lynch” when white individuals, lawmen or mobs killed three or four black men and boys a week, enjoyed impunity and often the approval of governors, senators and local officials.

Even leading Northern politicians greeted lynching with indifferent shrugs or vague support. “Progressive” President Theodore Roosevelt, for example, advocated white “racial selfishness” and stated, “It is wholly impossible to avoid conflicts with the weaker races.” While TR stated his opposition to lynching, he also sternly lectured black audiences that their “rapists and criminals did more harm to their race than any white man can possibly do them.”

One of the historical echoes of Wilson’s striking testimony can be found in South Carolina Sen. Ben Tillman’s classic defense of lynching on the floor of Congress on Jan. 21, 1907. During his term as governor and four terms in the U.S. Senate, Tillman considered lynching a messy but needed part of the legal process.

This grew out of the Senator’s vision of a giant struggle “between barbarism and civilization, between the African and the Caucasian for mastery.” Violence assured the white community that the black enemies would be kept “in their place,” segregated, working for and fearful of whites and never dare to demand the right to vote, sue, testify in court or sit on a jury.

Tillman began by strumming a familiar Southern white chord: “the black rapist.” Tillman said: “I would lead a mob to seek the brute who had ravished a woman.” The “brute” he said, was “negroes . . . a black flood of semi-barbarians,” “a lurking demon,” “the Beast leans forward, huge and black.”

In Tillman’s view, the problem began when President Abraham Lincoln’s “new birth of freedom” forever changed obedient slaves into human monsters: “murder and rape become a monomania, the negro becomes a fiend in human form.” Tillman’s fellow whites faced “an irrepressible conflict between civilization and barbarism.”

Despite this terror, Tillman said he was not in favor of burning accused rapists to death. Neither was he a bigot: “I have never called them baboons.” But he added, “some are so near akin to the monkey . . . the missing link,” “a creature in human form.”

Tillman’s words assured those who lynched African-Americans that they had the political support and the personal sympathy of powerful people and government institutions.

In our age of repeated police shootings of unarmed black men and boys, North and South, our schools and media rarely shine a light on America’s centuries of lynching nor the racist images and language that accompanied the violence. No leader of either race can seem to get a national discussion going about this painful topic.

More than a century ago, Tillman spun his provocative visions: “brute,” “lurking demon,” “bulk” “fiend.” Did Tillman’s words somehow seep into the largely white St. Louis Grand Jury that announced, in effect, that suspect Michael Brown did not deserve to live? Or the Staten Island Grand Jury that let off the police killers of Eric Garner?

Does Tillman’s fearful, angry nightmare still haunt today’s police departments, grand juries and many whites, even those who oppose racism? Hasn’t enough already gone wrong to prove we need to talk to each other openly and honestly before more bodies of unarmed black men and boys are left in the street like refuse?

William Loren Katz is the author of Black Indians: A Hidden Heritage and forty other history books. His website is: www.williamlkatz.com

Google “white devils”. 20 million hits.

Now tell me that “black devils” as racism is real.

The racism comes from blacks, not flows towards them.

I have felt for a long time that whites are not just afraid of blacks but also of their own projected anger (forgive me; I am no psychiatrist). My meaning: blacks are correct in that we cannot possibly know blacks without experiencing what they have experienced. But we understand some things. For example, I have been stopped for no reason by Southern ‘bubba’ cops on two occasions. It was over quickly, but I did not like it. Imagine what blacks feel. Deep down only the most obtuse will not recognize the great wrongs we have done to blacks. If their experience would have been ours, we would be angry, vengeful, and even murderous. That is what we expect blacks to feel, and it is what keeps us frightened and repressive—always looking to pre-empt the rise of the Mau-mau’s.

Joe, as I get older, I hesitate to revisit some of these horrors, so I didn’t look at the link. I really don’t need to – I’m well aware of the depth and breadth of human depravity. I would liken what’s in that link to cannibalism which stops short of eating the main course. All human populations are capable of descent into barbarism – there’s nothing ‘exceptional’ about Americans. In fact, the lack of homogeneous cultural reference points in our diverse society probably puts these atrocities closer to the threshold of occurrence under conditions of economic or environmental collapse. The “Lynching” era was such a period.

Abe mentioned an excerpt from Gustave Gilbert’s book; he was the psychologist assigned to Nuremberg to evaluate the principal war criminals. An interesting parallel is the case of Lieutenant Colonel Douglas M. Kelley, M.D. He was the U.S. Army psychiatrist assigned to the same task. His book was called, “22 Cells in Nuremberg”, if I remember correctly, and it was published shortly before Gilbert’s book. It’s very dry reading, and both books are difficult to find today. Kelley said:

“I shared the opinion of ethnologists and politicians alike that Nazism was a socio-cultural disease which, while it had been epidemic only among our enemies, was endemic in all parts of the world. I shared the fear that sometime in the future it might become epidemic in my own nation”.

Kelley and Gilbert apparently had some philosophical differences, and some claims were made that they were in a race to “publish first”. Insinuations were made that Kelley saw political motivations at the heart of many aspects of the proceedings, while Gilbert may have been motivated by loyalty to rigid doctrinal concepts. Kelley was a proponent of the Rorschach test, which has since fallen into disuse. Some claim that the demise of Rorschach was also motivated by politics rather than scientific efficacy – a political battle inside psychiatry not unlike the battle between “Lumpers and Splitters” in anthropology.

Kelley, for example, based on Rorschach examination, determined that Robert Ley had organic brain damage. (The test tends to focus on interpretation of linguistic aberrations in the subject.) Ley committed suicide in his cell, and an autopsy confirmed brain lesions exactly where Kelley said they would be.

Kelley’s postwar life remains an enigma – though a brilliant man with an astonishingly promising career ahead of him – he even had a television show at one point – Kelley committed suicide out of a clear blue sky. The method was cyanide poisoning. Insiders claim he used a cyanide capsule he confiscated from Hermann Goering, but the “official” story is that he made the cyanide in his chemistry laboratory in the basement.

Have you ever heard that truism that everyone on earth is only separated from everyone else on earth by less the six people? I’m only separated from Douglas Kelley by one person. Scary, isn’t it?

F.G., sometimes I too fear that a socio-cultural disease has infected our American society. By now you would think our discussion would center on how to build better communities. Instead, we are still playing tug of war, between race and police brutality. All I can say, is these people who applaud police officers who use excessive force…well I hope they never experience such violence.

Thanks F.G. for your comment. Your input is worth the wait.

Joe Tedesky

You’re really just a bunch of children, replacing hard realities and objectivity with prejudice that serves you, soothes you, and helps you make sense of a world you don’t like, instead of assuming any responsibility.

That’s lifted from the last post of the Ferguson thread. The fellow is raging because us do-gooders just don’t understand how to handle the “Ns”.

That’s not any kind of a new attitude. As the current thread author says, in the old days – when White Men didn’t have so many restraints – lynching was one of the best weapons to keep the black “Menace to American Civilization” in its place.

https://archive.org/details/negromenacetoame00shuf

Don’t go to the link unless you have a very strong stomach, for though I might have seen books as bad, I’ve never seen worse. It’s utterly vile!

The author devoted quite a bit of text to a case where a negro murdered a little girl. Not “allegedly” murdered a little girl, the Whites always KNEW! In this case they weren’t content to merely hang him – they slowly tortured him to death. And this was a public torture session – the photographs showed a huge crowd. Red hot irons on assorted body parts started the process, then on to burning him alive. Something like modern-day “Settlers” do in Israel today.

This fellow represented the times. The ‘lynching’ of blacks was extremely common. In Indiana the KKK had total control of the state for a time following WW1.

It’s easier for the Good Christian Whites these days – let the unchecked police do their dirty work for them, then defend those goons with guns & badges to the hilt. So far the scheme is working to perfection.

Zachary I read some of the book on your suggested (with warning) link. I’d love to hear what F.G. would say about that book. I say this since the author talks about anthropology, and I believe that is F.G.’s field.

I don’t mine having a heated debate, but ‘anonymous’ who appeared on the last Ferguson story, wasn’t debating any of us. Instead, ‘anonymous’ was just attacking us, and belittling all of our natures. People like us really upset people like ‘anonymous’. They are blinded by their prejudice of some kind.

You, Zachary, are a better person. I say this to you, because you always seem to love researching topics. Which is more that many will do. You may not always get it right, but you at least try and attempt to gain more and more knowledge of a subject, before typing your comments. I always look forward to your post, as you provide us with reference, as well as your intellect.

Take care Joe Tedesky

Joe, my comment is “awaiting moderation”. If it gets “unmoderated”, you’ll have some interesting observations, in my opinion.

F.G. I hope you didn’t mine me mentioning your name, but you always have something worth a read…anyway, will wait to see what you got.

Zachary, don’t read into my comment…’You may not always get it right’ that could also mean, you don’t always get it wrong. All I am saying is, your human. You certainly do the research, that’s for sure.

Joe Tedesky

A few years ago my predominantly white suburban neighborhood was experiencing home break ins. There were more than one eye witness account of people seeing a black man traveling through our back yards. Oh the fear of some was…well over the top. I was even accused of ‘liking blacks’ when I didn’t hurry to grab my pitch fork. At the time I was just attempting to somehow process this whole thing in my mine. I looked pretty good when the burglar was caught. The thief was a 35 year old white guy. He was wrestled to the ground by a 70 year old man who had chased him out of his kitchen in pursuit. The 70 year old had the body and health of a 45 year old. The 35 year old robber was a drug addict.

I went to the addicts court hearing to support my neighbor who had had her house broken into, by this guy. It turned out the 35 year old home invader knew the lay out of her house, since he once dated a young lady who had previously lived in my neighbors home. The only question I have to this day is…where is the black guy?

Mark Twain’s tales are tame compared to reality. Some of his works have been banned because of the realistic vernacular they contain. Critics have accused him of exploiting the oral heritage of contemporary cultural sources, transcribing it and passing it off as original work. His depictions of race relations have been labeled racist plagiarism by his detractors and exploitative creativity by his apologists.

Truth is a matter of consensus, nothing more. You can tell the truth you know, and repeat the truth you’ve been told, but the burden of belief is always a matter of choice. Knowing, at the end of the day, depends on the faith you have in your own perceptions and the trust you place in the tellers of the tales.

My grandfather was already a grown man when Mark Twain died. His father was a Civil War veteran. I grew up on the ‘oral tradition’ that informed Twain’s tales. My grandfather could recite epic poems – some of them required more than an hour to tell, in the folk tradition of that era. They were laced with ribald humor, double entendre, naughty insinuations, startling insights, shocking realities and a healthy dose of what the Antebellum South was really all about. Twain would have been insanely jealous, but I doubt he could have found a publisher willing to take the risk. At my age then, I didn’t ‘get’ most of the ribald humor or the cryptic inferences. It was only after I was older that my recollections began to assemble themselves in perceptible patterns. To a kid, it’s the rhythm and the rhyme that fascinates. More often than not, those tales put me to sleep…which in retrospect was probably the intended outcome.

But what I know, without any doubt, is what’s really “Gone with the Wind”. It’s a culture of institutionalized, socially condoned, serial rape. It’s a tradition of sexual exploitation and depraved immorality unrivaled anywhere else in western history. And a segment of our society is angry to this day that it ended.

Whenever I see a typical Hollywood rendition of those fine, upstanding “Genuine Beauregard” Southern ladies with their prim and proper huffy attitudes, I have to wonder. Don’t they realize their fathers, husbands and brothers are all…well, you know, living the sporting life? In all those tales about all that ribaldry, there is never an episode when a white woman has an unwanted Black child. Surely, if Black men were so prolifically engaged, there would have been at least a few fine, upstanding Southern White Christian women who would have been morally obligated to carry those children to full term. Unless there were, by some chance, more than a few abortionists practicing happily among the stalwart founders of Jerry Falwell’s misguided “moral majority”.

The reality is, all those beastly Black rapists are the vile product of imaginations set ablaze by perceived sexual and financial inadequacy. That is compounded by the reality that most white people, then as well as now, don’t have much to show for themselves except for the fact that they aren’t Black. Equality destroys any pretense of dignity their sense racial superiority might confer. Poverty is at the heart of all of this. As long as our society functions to make the rich richer and the poor poorer, these hate crimes will continue, and probably escalate. It’s time to reign in the new owners of Plantation America. But you don’t have to believe me. That’s up to you.

Does Tillman’s fearful, angry nightmare still haunt today’s police departments, grand juries and many whites, even those who oppose racism?

Duh! Does ocean water taste salty? Do people living at the South Pole need to keep their brass monkeys indoors? Police departments have too many employees who are low-grade rednecks; who are too often administered by the same types. Wilson felt himself a “child”, and in mental terms actually was and still is. But so are his immediate superiors. The bosses higher-up are more the calculating types of the same mold as the people who masterminded the Civil War.

This essay really was a useful one for me – the introduction to the books I hadn’t known about overwhelmingly justified the time spent reading. Oddly enough, The Negro A Beast, despite the publication date of 1900, wasn’t among Google’s free ebooks. Fortunately somebody has put a copy on the internet.

http://www.thechristianidentityforum.net/downloads/Negro-Beast.pdf

Dehumanization describes the denial of “humanness” to other people. It is theorized to take on two forms: animalistic dehumanization, which is employed on a largely intergroup basis, and mechanistic dehumanization, which is employed on a largely interpersonal basis.

According to psychologist Nick Haslam http://general.utpb.edu/FAC/hughes_j/Haslam%20on%20dehumanization.pdf , the animalistic form of dehumanization occurs when uniquely human characteristics (e.g., refinement, moral sensibility) are denied to an outgroup. People that suffer animalistic dehumanization are seen as amoral, unintelligent, and lacking self-control, and they are likened to animals. This has happened with Black Americans in the United States. While usually employed on an intergroup basis, animalistic dehumanization can occur on an interpersonal basis as well.

The propaganda model of Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argues that corporate media are able to carry out large-scale, successful dehumanization campaigns when they promote the goals (profit-making) that the corporations are contractually obliged to maximise. In both democracies and dictatorships, state media are also capable of carrying out dehumanization campaigns, to the extent with which the population is unable to counteract the dehumanizing memes.

“A propaganda system will consistently portray people abused in enemy states as worthy victims, whereas those treated with equal or greater severity by its own government or clients will be unworthy. The evidence of worth may be read from the extent and character of attention and indignation.”

– Herman, Edward S. and Noam Chomsky. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: the Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York: Pantheon. p. 37