Forty years after their powerful union was crushed in an early battle of neoliberalism, still defiant ex-miners marched last weekend to their closed Yorkshire pit to hear their 86-year old former leader reflect on their struggle, reports Joe Lauria.

By Joe Lauria

in Hatfield, South Yorkshire, England

Special to Consortium News

It was the major battle of the neoliberal revolution in Britain led by Margaret Thatcher: her war against the politically powerful National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), forcing a strike that lasted more than a year.

When it was over, more than 100 mines were closed, the union’s back was broken and the hallmarks of economic neoliberalism — privatization, erosion of social services and escalating income inequality — were entrenched.

Maggie, the Immortal Enemy

The hatred for Thatcher, who died in 2013, is still palpable here. The ex-miners and their wives sported t-shirts that read, “Still Hate Thatcher” and one pictured her in the place of a striking miner walking in a field about to be clubbed over the head by a mounted bobby.

One former miner, his dog wearing a banner reading, “I eat scabs,” chanted, “Maggie, Maggie, Maggie: Dead, Dead, Dead.”

During the strike their main slogan had been: “Coal Not Dole.” There were others, too crude to repeat, that reviled Thatcher.

Many of the miners, especially the older ones, never worked again and remained on the dole for the rest of their lives. Working people, especially in former mining and industrial areas, still haven’t emerged from more than 40 years of neoliberal repression.

But last weekend their fighting spirit was revived in one South Yorkshire region as hundreds of former miners and their families marched through the streets of Dunscroft, Stainforth and Hatfield to their former pit, with its rusted gear head still dominating the landscape.

Video of march Saturday to the closed Hatfield mine and Scargill speech. 1 hr, 23 m. (Camera: Joe Lauria. Editor: Cathy Vogan for Consortium News.)

From there, lead by pipers and a brass band, they marched to the Hatfield Main Club — the “pit club” — where they heard an address from the man they still revere as their champion: 86-year old Arthur Scargill, the firebrand leader of the NUM at the time of the strike.

Still on Fire

The son of a coal miner (and Communist Party member), Scargill left school in 1953 at age 15 to begin mining at the Woolley Colliery, in the West Riding of Yorkshire. He worked in the pit for 19 years, joining the Young Communist League in 1955 and becoming involved with the NUM. He joined the British Labour Party in 1962 (and quit them in 1996 to lead the Socialist Labour Party)

Scargill is credited with developing the tactic of flying pickets, which is busing thousands of striking miners to various strike locations to try to hinder scabs from entering a pit. He used it to win The Battle of Saltley Gate, a mass picketing of a fuel storage depot in Birmingham during a national miners’ strike in February 1972, which ended in a victory for the miners.

In 1973 as a union representative he went down a pit with a rescue team at a disaster at the Lofthouse Colliery in West Yorkshire that killed seven miners. Researching 19th century plans for the mine he was able to prove that the National Coal Board, the government agency that ran the nationalized coal industry, could have prevented the accident.

As leader of the Yorkshire miners, Scargill played a key role in organizing the 1974 strike that led Tory Prime Minister Edward Heath to call an early general election that Heath ultimately lost, leading to a Labour government.

Scargill become NUM leader in 1981. In March 1983, he called the newly-appointed head of the National Coal Board, Scottish-born American Ian MacGregor, a “hatchet man.” Scargill told the BBC: “The policies of this government are clear — to destroy the coal mining industry and the NUM.”

Scargill turned out to be right about Thatcher aiming to destroy the industry. He told the crowd in Hatfield last weekend that just eight months after MacGregor’s appointment, NUM local chapters, realizing what was about to happen, voted to go on strike.

With that statement, Scargill on Saturday confronted what he said were two myths still widely believed about the 1984 strike: 1). that it began in 1984, and 2). that the strike was never authorized by a vote.

Scargill has been criticized for many things, not only by the government, but by miners who did not agree with the strike. The principal criticisms are that he did not hold a national strike ballot of the NUM’s rank and file and that he chose the beginning of spring (March) rather than the start of winter for a coal strike. He addressed both issues last weekend in Hatfield.

It’s widely reported the strike began March 6, 1984 with MacGregor’s announcement that 20 pits would close with the loss of 20,000 jobs. Scargill said the strike actually began in November 1983. (Everyone agrees it ended in March 1985).

Scargill said it was easy to see the battle looming as soon as MacGregor, who had undermined unions for 40 years as a corporate executive in the U.S., had been appointed to head the government coal board in March 1983. He said:

“The Tory government, led by Margaret Thatcher, [booing in the crowd] declared war on the NUM. They’d been preparing for a showdown with the Union since before the 1979 general election. They couldn’t forget the victorious miner strikes of 1969, 1972 and 1974.”

Because of this, he said the strike was begun in November 1983, ahead of winter, and not in March 1984. The way it was begun and carried on is still controversial, because the NUM relied on local voting, rather than on a national ballot, and on flying pickets of strikers bused to pits where miners had not voted to strike.

“It’s often been said that the miners failed in 1984 because we didn’t have a ballot, [that] it was an unlawful fight. It’s a lie,” Scargill said at the weekend. “We took action in accordance with our rules and Rule 41 gives an area the right, when it’s under attack, to take industrial action.”

Scargill clearly thought the miners were under attack with the appointment of MacGregor even before any pit closures were announced. “Therefore we called a special Conference in October 1983,” he said. “The miners dispute didn’t begin in March 1984. And for the benefit of a representative from The Sun, if one is here, 1983 is before 1984,” he joked.

“They said it’s the wrong time of the year to have a [coal] strike in March. We started it in November,” he said.

By March 1, 1984 the first five pits had closed and 20 more were on the way. Two days later, at a national executive committee meeting, Scotland and Yorkshire sought permission to take action, and a further 180,000 miners went on strike, Scargill said.

On April 19, a special national delegate’s conference voted to reject holding a national ballot and backed the now 190,000 miners on strike, he said.

He quotes Thatcher in her memoir admitting there were only three weeks supply of coal left. Scargill said mass picketing at three locations in Scotland, Wales and Yorkshire could have won the strike for the miners in October, but they never arrived because the full membership was not behind the strike.

Nevertheless, he quotes Thatcher as saying that “the government had to use everything in their arsenal to defeat the NUM.”

Orgreave

Long shields of the type used at Orgreave of the West Midlands Police. (West Midlands Police/Wikipedia)

The dispute was marred by violence, none worse than at Orgreave, a coking plant in South Yorkshire, 28 miles from here.

“We knew that if we could amass enough pickets at Orgreave, we would have a chance,” Scargill said.

The worst day of police violence came on June 18, 1984 but Scargill says he witnessed violence there earlier, on May 23. He said a mass picket that day “terrified the authorities.”

Scargill said a minister in Thatcher’s government at the time told him that not only was the deployment of large numbers of police forces considered, but also the British army.

By June 18, there were thousands of picketers at Orgreave from all over Britain, he said. The cops came from all over too. “A military police force, armed to the teeth with staves, truncheons, dogs, short shields, long shields — and boy, did they intend to use them,” Scargill said.

Historian Tristram Hunt wrote in The Guardian the confrontation was “almost medieval in its choreography … at various stages a siege, a battle, a chase, a rout and, finally, a brutal example of legalised state violence.”

A report by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) in 2015 cited “evidence of excessive violence by police officers, a false narrative from police exaggerating violence by miners, perjury by officers giving evidence to prosecute the arrested men, and an apparent cover-up of that perjury by senior officers.”

Nearly 100 picketers were charged with riot or violent disorder, which the human rights lawyer Michael Mansfield told The Times was “the worst example of a mass frame-up in this country, this century.”

Ending the Strike

Scargill said it was another lie that he had refused to negotiate with the government during the strike. He said he met with them five times and thought he had a deal. He blamed MacGregor and Thatcher for stopping it according to the disclosure in 2014 of Downing Street minutes.

Scargill said there was another deal in October 1984 that he said was sabotaged by the Trades Union Congress (TUC). In February 1985 a special delegates conference of the union voted to continue the strike, but five days later five union areas agreed at a conference to return to work without a settlement.

“I’ve never understood it. I’ve never understood the thinking or the forces behind it,” Scargill said.

In September 1984, a High Court judge ruled that the strike was illegal because there had never been a national ballot, leading to a freezing of the union’s assets. The case had been brought to the High Court by separate groups of mineworkers from Yorkshire and Derbyshire.

According to the People’s History Museum in Manchester, these were among the reasons the strike ended in defeat for the miners:

“On 3 March 1985, following a narrow majority decision by the NUM executive, the miners returned to work, at many pits processing with banners and bands. As the strike progressed the hardship experienced by the miners intensified.

The NUM’s assets had been frozen in October 1984 and miners were becoming increasingly dependent on voluntary contributions. A $1 million donation from Soviet miners, authorised by future Soviet Union leader Mikhail Gorbachev, was eventually blocked so that the USSR could cultivate relations with western governments.

The Thatcher government’s policy of stockpiling coal meant that the power stations had remained open during the 1984 to 1985 winter, and by early 1985 increasing numbers of miners were drifting back to work; remaining on strike was no longer an option.”

Scargill called the strike “the greatest workers’ fight since the days of the Chartists.”

“It’s a privilege to be here today, 40 years on from the most historic dispute in the century,” Scargill told the crowd.

“It’s a privilege to talk to you and to thank you for what you did, not only the men and women involved, but their children, a lot them who are here today as adults. I tell you, what you’ve done: you have marched into history.”

Solidarity With Gaza

Scargill began his address to the ex-miners and their families with a strong defense of the people of Gaza and an equally strong condemnation of Israel.

He said “the slaughter of more than 30,000 innocent people … in Gaza is nothing less than genocide. The perpetrators should be arrested and jailed for life.”

Scargill said it’s “terrible that the fascist state of Israel has continuously bombed and shelled Gaza … for nearly 5 months. These territories are the land of Palestine, which Israel has unlawfully occupied since 1967 and unless Israel withdraws, I call upon other nations to force back this fascist state.”

If the U.S. and Britain “can unlawfully invade States like Grenada, Iraq or Libya, they should be part and parcel of a force together with all the Arab states driving Israel physically back from the occupied territories.”

Despised

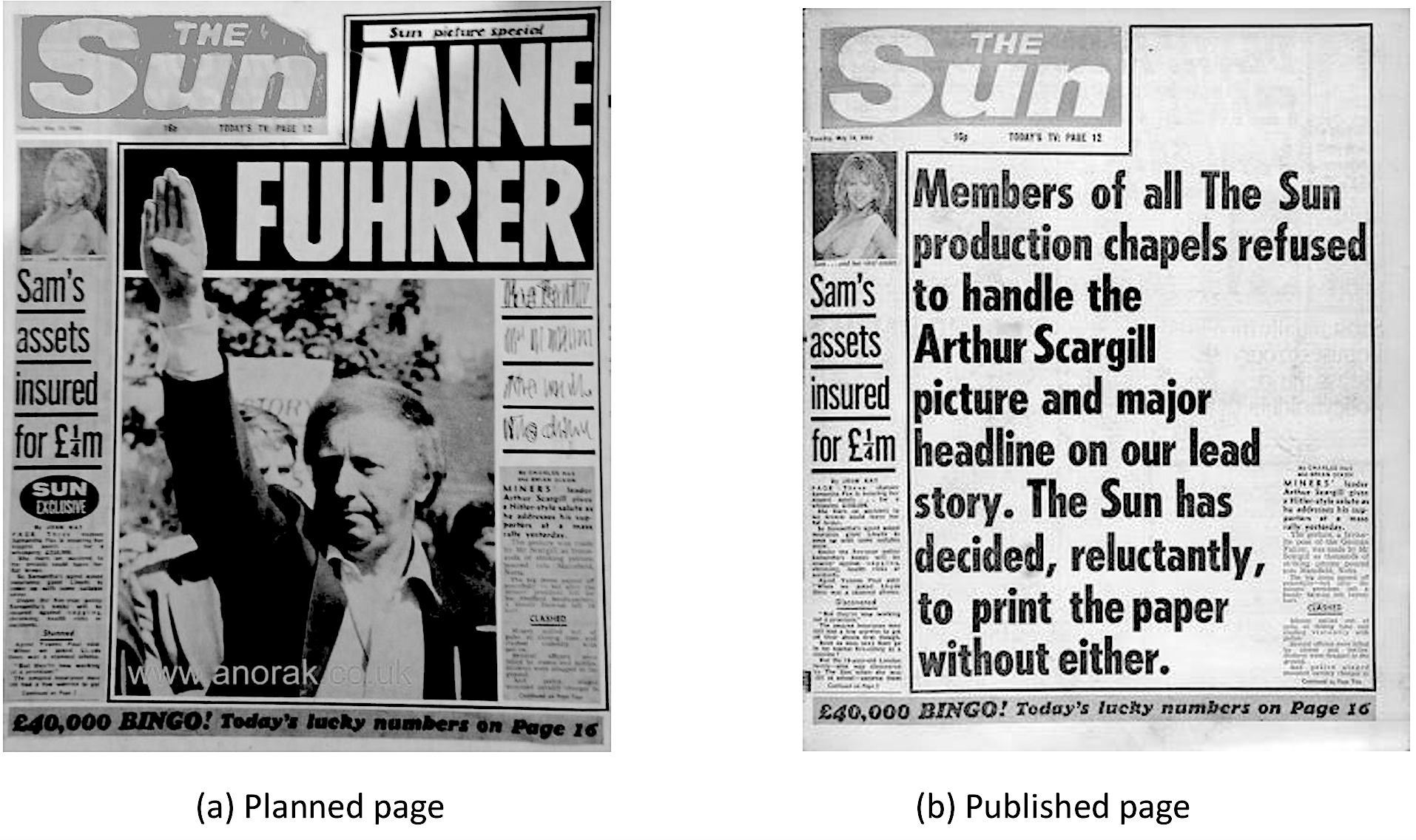

Scargill became the mortal enemy of Thatcher and the Murdoch gutter press. The Sun portrayed him in a cartoon with a Hitler mustache. They tried to make him into both a Nazi and a pro-Soviet communist.

However, the printers at The Sun, before Murdoch crushed their union a year after Thatcher beat the miners, refused to publish a headline labelling Scargill “Mine Fuerher.”

The Sun, May 15, 1984. Christopher Hart: “Metaphor and Intertextuality in Media Framings of the (1984-1985) British Miner’s Strike: A Multimodal Analysis”

Scargill pointed out that Thatcher so hated him that she devoted an entire chapter about him in her memoirs. “I think she fancied me,” he quipped.

In Dunscroft, Four Decades Ago

By coincidence, it was in this very town of Dunscroft where I lived with the striking miners for a month in 1984, going with them to the picket lines and the soup kitchens, attending their meetings and writing about their strike in a diary that reached 40,000 words.

There were two camps among the strikers: the mostly younger miners wanted the strike to bring down the Thatcher government, the way the miners had helped bring down the government of Edward Heath in 1974.

The mostly older, and more conservative miners, who were more likely to have families, only wanted to keep their jobs and had little time for the radicals.

Legacy of the Strike

George Galloway with Arthur Scargill at the march in Hatfield, South Yorkshire, commemorating 40 years after the miners’ strike. (Joe Lauria)

Thatcher was implementing the Chicago School anti-Keynesian, neoliberal economic policies in which government got out of the way for private industry and financial markets to upend society to make maximum profits.

It was a revival of 19th century laissez-faire economics, in which government intervention to create a fairer society is blocked. It’s like removing the referee from a match: at first excitement rises with no fouls called, but eventually the game dissolves into chaos, where the strong dominate and set the rules.

One of the first things the neoliberal revolution had to do was destroy the strongest defenders of the old order: the labor unions. This took place in two high-profile operations.

In the U.S., Ronald Reagan took on and defeated the air-traffic controllers in 1981. In Britain, Thatcher confronted the mineworkers two years later. She brought in MacGregor with a plan to close ultimately 115 pits. (The mines were nationalized in 1947 and about 800 pits had been closed by both Conservative and Labour governments between 1947 and 1984.)

Coal miners had been among the most militant workers in British industrial history — a force Thatcher had to reckon with. For instance, in 1912, more than a million miners had gone on strike to win a national minimum wage.

In 1926, striking miners, fighting wage cuts, were joined in sympathy by other unions in what became a General Strike of about 1.5 million workers. (Ian MacGregor’s brothers drove trams in Glasgow to break the strike.)

Winston Churchill, then chancellor of the Exchequer, wanted armed soldiers to confront the strikers. He stopped the supply of paper to the strikers’ newspaper, The British Worker. The General Strike was over in nine days but the miners carried on, eventually lost and had their wages cut. But their power spooked Britain’s rulers.

As ex-miner Mick Mick Lanaghan said at the Hatfield pit on Saturday:

“It was nine days before the TUC [Trades Union Congress] sold us out and left us to fight on alone for nine bitter, starvation-filled months during which time Churchill put machine guns at the pit heads and tanks on the streets, armored cars on the dock and swore to drive us back down our holes like rats. When Arthur Cook [General Secretary of the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain from 1924 until 1931] said we would let grass grow on the pulley wheels before we’d submit to longer hours and still more wages reduction, Churchill said he’d make us eat the grass.”

A 50-day miners’ strike in 1972 ended in victory against the Conservative Edward Heath government with pay rises for the miners. In 1974, the miners again showed their political might with a strike that effectively brought down the Heath government.

These were all lessons for Thatcher.

A University of Oxford study last year concluded:

“The defeat of the [1984] strike led very quickly to the closure of most coal mines, a general deindustrialisation of the economy, the rapid privatisation of nationalised industries, the shattering of organised labour, growing unemployment, the hollowing-out of mining and other working-class communities, and a steady increase in social inequality in British society. It marked, in a word, the end of twentieth-century Britain and the ushering in of twenty-first century Britain characterised by speculative capitalism, the dismantling of workers’ protections and the rise of the gig economy.”

For example, just a year after the strike ended, Rupert Murdoch broke the printers’ union by moving his shop from Fleet Street to Wapping.

Newly elected MP George Galloway of the Workers’ Party of Britain joined Scargill at the end of the march in Hatfield. In a video afterward, Galloway gave his perspective on the legacy of the 1984 strike.

“The miners had to win if the working class movement in Britain was to survive,” he said.

“If the miners had won, how different the history of our country would have been. That’s why Thatcher strove might and main to destroy the miner’s union, because they were everything that she hated. They proved that there is such a thing as society. .. It was to end in broken hearts, in a broken industry, in a broken economy, in a broken Britain. But we revere the memory of the struggle of the mineworkers 40 years on.”

It was the striking miners who put up the most valiant struggle against the imposition of Thatcher’s neoliberal economics. The miners’ defeat was a defeat for all working people in the West.

Was last weekend a spark that could renew the battle against 40 years of repression? Can it be defeated and reversed? Can heavy industries like coal and steel return? The former miners and their families seem to think so.

For now, though, it was a day tinged with the sadness of a culture that once was: thriving, working class communities of people who lived very hard lives with dignity.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former U.N. correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and other newspapers, including The Montreal Gazette, the London Daily Mail and The Star of Johannesburg. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London, a financial reporter for Bloomberg News and began his professional work as a 19-year old stringer for The New York Times. He is the author of two books, A Political Odyssey, with Sen. Mike Gravel, foreword by Daniel Ellsberg; and How I Lost By Hillary Clinton, foreword by Julian Assange. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe

Today, Saturday March 16, 2024, Naked Capitalism has an article entitled, “What is China’s Future? Economic Decline or the Next Industrial Revolution?”.

I hope that commenters and readers, here, might be willing to read or view a discussion among Radhika Desai, Michael Hudson, and Richard “Mick” Dunford, as itt suggests an alternative to “western” economic parasitism.

Hopefully, knee-jerk prejudice may be replaced with a more receptive willingness to learn from others, despite the allegiance to the disdain of anything “not invented here”.

Looking forward, as our society must move beyond neoliberal limitation and control, we must examine other possible means of economic planning to achieve social justice beyond the destructive policies of crapified capitalism and elite domination.

I realize that many are unwilling to consider the possibility that other human

societies might well have conceived and implemented policies superior to our own.

Yet dire necessity must impell us to more open mindedness and a genuine willingness to see beyond the clap trap and cant of the west’s (primarily the U$)

narrow and elitist rewarding mentality, as the cost to the many and the planet, itself, cannot much longer be tolerated or embraced.

this article is a good representation of our recent times. through it all we have weathered the likes of thatcher,blair,boris johnson,sunak,reagan,bush(both senior and junior),clinton,obama,trump and biden. they all were or are enemies of the common man. what a disgrace!

Thank you, Joe, for this very moving and informative history. It helps to explain the dark period through which the UK is passing, along with much of the rest of the world. But it also reminds us of the inspiring class solidarity which prevailed at that time in Britain.

I was not in the UK in 1984, but a few years earlier I was fortunate to experience the exemplary support which the miners (along with the postal workers) extended to the Grunwick strikers. The betrayal of that strike was an evil omen of what was to come.

Thank you for this superb recounting, which informs well beyond most “histories” of this event and those times.

Thatcher quickly gained the nickname, “Maggot”, which, if it is considered demeaning, must apply only to the bluebottle fly.

Thatcher and Reagan began the neoliberal destruction, yet it took Blair and Clinton to embrace it fully in bipartisan “fashion”.

This was predation released on the many in the so-called “west”, and it continues, most brutally, enforced by the PMC and the political class, in thrall to oligarchic whimsy.

Kiss up and punch down is the credo of the media and academia alike.

Flyover country is the lot of the many.

Stable local economy throughout the “west” has been destroyed and the Divine Right of Money rules.

Any honest advance of western “civilization” must end that divinity just as the Divine Right of Kings was ended.

That can come about only when those who lie is into war (for profit), set up torture programs (for fun) and practice genocide (as has the U$ from the moment the Calvinist trio of Mayflower “Pilgrims”, Huguenot, and Dutch Reformed (who had a quaint little mercantile experiment at a place known as New Amsterdam – it has a different name now) created the still unexamined assumptions of U$ian superiority, morally, culturally, and, most especially, genetically.

When I ask people if they are familiar with the Declaration of Independence, the answer, almost invariably, is “yes”.

When I ask about the reference to “… the Savages at our frontier …” the response is either, “huh?”, or, “Well, they called them Savages only because they were not

Christians.”

Like a certain nation, today, the U$ (and South African) Calvinists believed that had an agreement, a covenant, with the Big Guy, not Genicide Joey, but Sky Daddy.

No doubt, Maggot et al, like U$ bankers, certainly must believe that they “do” Gawd’s Work.

Power to the people.

Let the many decide policy.

The elite projects of murder and mayhem, of deceit and destruction, never have and never will serve the genuine needs of humanity.

If there is any divine endeavor, is it not the struggle of the many to build a sane, just, and sustainable world?

My apologies for going off topic.

Joe Lauria, Lionel, and Saul Takahashi, appear today, Friday, March 15, 2024 on CrossTalk, discussing genocide.

I urge all who comment here and read Consortium News to view this episode.

IMO.

As evil and guilty as Thatcher definitely was, Scargill was just as guilty for ruining the miners lives. Scargill’s primary motive was to bring down the democratically elected government – at whatever cost. There was no diplomacy or grown up discussions on either side, heels were dug in and the miners were left in the middle, in a fight that they couldn’t possibly win, although the conditions of their loss could have been less painful if there had been intelligent diplomacy and agreements.

The south wales valleys are still economically depressed from the fall-out of this capitalism versus marxism war, and as usual in wars, it’s the little people who suffer. I have great sympathy for the miners and great hatred for Thatcherism, but Scargill and Thatcher were two cheeks of the same backside, both responsible for the miners plight.

Thank you, Joe. He has lost nothing of the old fire. It was turning point not only in British industrial history, political history and even, given the internationalist role of the NUM, in the history of the cold War.

Thank you for reporting this important and significant event.

“This was violence far in excess of anything I’d ever witnessed: We couldn’t believe it when the BBC reversed footage on the Six O’Clock News to suggest the miners had attacked the police” — An independent police complaints commission found in the miners’ favour that the BBC had reversed footage but they continue to deny it.

hxxps://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/dec/16/battle-orgreave-lesley-boulton-photograph

A significant turning point in British history. I wonder how it would all have turned out if Thatcher and Reagan hadn’t forced neoliberalism onto their two countries, and by extension the collective west.

It was a dark time then, but is even darker now as we descend in totalitarianism.

Thank You Joe

The irony of all this is the factcwe need the burning of coal to end as part of human survival. Thatchers deliberate brutality to break the power of the working class for neoliberalism had environmental benefits.

Back in the 80’s, here in the Western US, the coal fired plants were required to start installing water scrubbers that would remove 80%-90% of the SO2 and particulates from the flue gas stream before it went to atmosphere. Expensive to install and operate, so some of the owners just shut down, putting a lot of people in those small Western towns out of work. I remember a bumper sticker from that time “Let the Bastards Freeze in the Dark”. Another aspect of neoliberalism is deregulation. Deregulation in this case, to be able to operate without the scrubbers, to keep sending flue gas straight to atmosphere.

I could tell a 100 stories like this across the different industries, and industrial facilities over the 35 years I worked in them. If you had an electron microscope, you couldn’t locate the care a neoliberal has for the environment. But you did say “irony”

Thanks Joe, I remember Reagan doing the Air Traffic Controllers, I didn’t remember the miner’s in England. It’s important to remember these battles.

Thank you, Joe!!! Thank you for witnessing this amazing event and sharing it with us via your reporting and video footage. So great to see Arthur Scargill still so full of militancy and determination. I recommend watching the entire YouTube video – very inspiring. I can’t thank you enough, Joe.