Exclusive: Photojournalism, the risky business of capturing images of war and other historic events, is under financial pressure like other aspects of journalism. Some photogs were encouraged when billionaire Bill Gates put himself in the picture in the 1990s, but that has not developed as some had hoped, reports Don North.

By Don North

When Microsoft founder Bill Gates bought the once-mighty French photo agency Sygma in 1999, there was hope that his vast financial resources and renowned business skills could rescue not only Sygma but the profession of photojournalism.

Photojournalists still had the hunger to capture on film the stark realities of war, but this dangerous task was increasingly compensated at shockingly low rates for the intrepid photographers whose skills at working a camera must be matched by their personal bravery.

Just last April, two more top combat photographers joined the ranks of those who died for their work. Tim Heatherington, 40, an Academy Award nominee for his Afghan film “Restrepo,” and Chris Hondos, 41, of Getty Images were killed in Libya while traveling with advancing rebel forces in the city of Misrata. They died in a hail of mortar fire.

Yet, for taking these risks and giving the world a close-up look at the triumphs and tragedies of recent history many photojournalists get paid barely enough to get by. One veteran French photojournalist recently reported earning 70 Euros (about $100) for three weeks work in Libya.

After returning from war zones, photojournalists also must cope with PTSD and other stresses with little or no support structure.

These dangers of photographing war have been a part of journalism at least since the 1930s and the advent of the 35 mm Leica camera, which let photographers take shots of the action as it unfolded and brought demands from editors for daring images at the front lines of battle.

But this heroic profession was undercut in recent decades by the disappearance of big glossy news magazines like Life and Look and the decline of Paris Match and Stern. The struggles of these magazines then hit the big photo agencies hard, the likes of Sygma, Sipa and Magnum and thus the photographers who worked for them.

Next, with the rise of the Internet and with the often illegal distribution of copyrighted images the world seemed to be treating photographs and the people who took them as devalued currency.

So, there was a flash of hope in the community of photojournalists when Gates, one of the world’s richest men, took an interest in buying up struggling photo agencies.

Working through his investment firm Corbis, he sought to preserve art, photographs and other historic images with the goal of delivering them into consumers’ homes for display in digital frames. His motives seemed to match the desire of the photojournalists who hoped their work could help educate future generations.

In 1995, Gates bought the huge Bettmann Archives, which included the library of United Press International. And in 1999, he added Sygma, the largest news photo agency in the world, bringing 40 million more images to the company’s collection.

The Corbis archives are stored 220 feet underground in a 1,000-acre limestone mine kept at 45 degrees Fahrenheit in Iron Mountain, Boyers, Pennsylvania. The archives use technology that is designed to preserve the art and photographs for centuries.

Yet, while the art and photographs are treated with the utmost care and stored at precise temperatures, it turned out that some of the professionals whose work was in the archives found themselves out in a different kind of cold.

Dominique Aubert, once a top photographer for Sygma, got a decidedly chilly reception from his old agency when he sought compensation for its distribution on the Internet of some of the 250,000 photographs that he shot for Sygma in war zones.

Aubert, a tall man whose amiable personality cloaked a fierce ambition to excel as a photojournalist, had spent eight years with Sygma, capturing images of conflicts from Afghanistan to Cambodia to the Middle East.

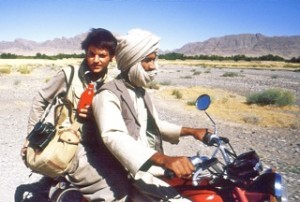

When I was on assignment for Newsweek in 1988, I personally watched the intrepid Aubert at work in Afghanistan. Traveling with the mujahedeen’s National Islamic Front on a mission to harass Soviet forces near Kandahar, we bounced along rough desert roads on motorcycles at high speeds with Dom and me perched precariously on the back seats with our cameras.

One day, I watched him get close enough to photograph Russian tanks and crews with a 300-millimeter lens, when one shell from the tank could have vaporized him. Risking his life for a photo went with the job.

However, by 1995, he recognized that the old world of photo agencies was in rapid decline and decided it was time to change his career. So he left behind Sygma and his quarter million photos and trained to become a pilot for a French airline company. He hoped the residuals for his photos would provide a source of continuing income.

Then, in 2000 during a trip to Los Angeles, Aubert discovered that some of his photos were being used in magazines for commercial advertising, which he had not authorized and had not been paid for.

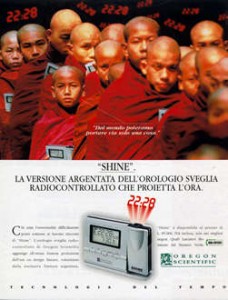

Later, he found on the Internet a photo he had taken in Burma of Buddhist monks. The image had been altered to show them carrying a brand of computers.

After researching what was going on, Aubert said he also discovered that Sygma had lost 750 original slides from the files. He made inquiries to and lodged complaints with Corbis/Sygma, but according to Aubert, he was rudely rebuffed and told that if he had complaints, “see us in court.”

Two years later he took that advice and hired a lawyer to confront Corbis/Sygma. After several years of tedious litigation in a French court, Aubert won a judgment of 102,000 Euros (or about $140,000), what he considered a modest sum but one that he reluctantly accepted.

“Tired of all the legal hassles I decided to let matters rest,” Aubert said. “I had enough of this crazy story and did not appeal the court decision.”

Corbis, however, did appeal, challenging the judgment. To the company’s chagrin, the Appellate Court of Paris last April not only upheld the decision but ordered Corbis to pay a judgment 16 times higher, more than 1.5 million Euros (or over $2 million).

As a result, Corbis closed down Sygma in France and dismissed its 29 employees, blaming Aubert.

“The fine is immensely disproportionate to the revenue opportunity with the images, and given previous decisions and other likely future lawsuits, Corbis came to the conclusion that it is no longer possible to maintain Sygma,” a Sygma spokeswoman said.

One month later, in an apparent attempt to avoid payment, Corbis decided to file for bankruptcy and the legal liquidation of Sygma France.

However, Aubert’s lawsuit continued to mushroom. In June, he was joined by four more former Sygma photographers Derek Hudson, Philippe Ledru, Moshe Milner and Michel Philippot in his legal case.

They hired a criminal lawyer, Jean-Philippe Hugot, to lodge a complaint with the District Attorney of Paris charging Sygma with fraudulent insolvency, breach of trust and misusing corporate assets by transferring them to its U.S.-based corporation Corbis/Sygma without financial compensation for its France-based organization, leaving it without the means to pay the 1.5 million Euro judgment.

The District Attorney of Paris has until the end of September to determine whether there is enough evidence to justify a criminal investigation.

Corbis says it is continuing to maintain the Sygma Access and Preservation Facility in a warehouse in Normandy, preserving 75 percent of the 50 million images from those photographers who have signed a contract to be represented by Corbis.

A liquidator is managing the 25 percent of files of photographers unrepresented and is trying to locate the owners. (It would seem an excellent time for photographers who at any time sent their work to Sygma to contact the liquidator : Mr. Stephane Gorrias, #1, Place Boeldieu, 75002, Paris, France.)

With the current attitude toward corporations in France similar to how many Americans feel about Wall Street banks there is little sympathy for Sygma and its creative efforts to avoid paying a court judgment in favor of an ex-worker.

There are plenty of precedents in courts on both sides of the Atlantic finding Corbis’s actions at odds with fair play in the marketplace.

Recently, a New York court awarded $472,000 to photographer Arthur Grace, who claimed Corbis lost 40,000 of his photos. The Court determined that Sygma, before it was acquired by Corbis, never had a system in New York for keeping track of images in its inventory. No record was kept of which images were sent to clients or which were returned.

As Bill Gates is the sole stockholder of Corbis, it may be fair to ask how much oversight he actually has over Corbis’s business practices. It may be understandable that he was not aware that Corbis/Sygma staff in Paris was allegedly playing fast and loose with photographers’ properties.

But Gates, as he built Microsoft into a corporate behemoth, was known for playing hardball with competitors and collaborators alike. Similar tactics have been noted at Corbis.

For instance, in July 2010, Infoflows Corporation, a small Seattle-based technology company, won a final judgment against Corbis in a Seattle court and was awarded $36 million in damages. The judge found that Corbis had appropriated Inflows technology during a software development partnership and tried to illegally patent it. Corbis is appealing the ruling.

Meanwhile, other photographers have accused Corbis of driving industry prices down in an attempt to acquire market share by squeezing smaller agents and independent photographers out of business.

A former photographer for Newsweek and Sygma, Allan Tannenbaum of New York, said Corbis has overwhelmed itself with more material than it can assimilate in a headlong rush to acquire as many agencies and images as possible.

However, Tannenbaum observes, “Corbis has done the photographic community one big favor, while sadly corporatizing and commoditizing what was once a collegial profession. Corbis has managed to alienate and unify so many photographers around the world who are now communicating on the Web.

“Our level of consciousness has been raised to the point where no one can sign a bad contract out of ignorance. We photographers have always been adaptable we just don’t want to adapt to our own extinction.”

Photojournalists also continue to hope that their profession, which captures images of humanity’s brightest triumphs and darkest tragedies, will survive as a means of bearing witness not just for people today but for centuries to come.

(Full disclosure: Having worked with Aubert in the past, I came to consider him a good friend.)

Don North started a career in journalism as a freelance photographer in Vietnam, and although he moved into film and video production, he has remained active as a still photographer mostly in conflict areas of the Middle East and Central America. North recently completed a book on war correspondence in WW II entitled Inappropriate Conduct. North’s recent documentary “Yesterday’s Enemies” looks back at the painful fallout from the civil war in El Salvador.

Hooray Jack!

Corbis/Bettmann also sells public domain U.S. Army photography that they have stamped in their online catalog with a Corbis Copyright. Photos that US Army cameramen have risked their lives to acquire.

I was at Sygma,rue Réaumur in Paris, in 1973,when we start the agency. photographer N°162. I remember Philippe Ledru but nobody speaks of all the others who built that incredible press agency, and for me the “suicide” of James Andanson our “starshooter” finishes and closes the story

Just won my case against Reuters after 23 years with them. Not only did they loose my negatives from 1983 to 1994 but my lawyer pinned them on fraudulent use of my work. French courts are great!

Congratulations Jack!

It occurs to me that with print magazines and news papers disappearing by the moment and photographers not being hired for projects that internet sites who steal our work are soon going to find no images left to utilize.

In addition to Chris Hondros and Tim Hetherington, Lucas Dolega and Anton Hammerl were killed this year.

A website has been set up to help Anton 3 children by selling prints by some of the world’s leading photographers. please visit and buy a print or make a donation: http://www.friendsofanton.org/

David: Thanks for pointing out the deaths of Hammerl and Dolega in Libya

recently. I will add their names to this article in future publications.

I would like to encourage our readers to visit the website you listed and

to buy a print or make a donation to help Anton’s family. Anton and his colleagues did important work in photographing the conflict in Libya, the least those of us who believe in the importance of photojournalism can do

now is to contribute what we can afford to comfort his family.

Don North

It really is about, as Thomas said, greed and a monopoly. The altering of Aubert’s photograph of Buddhist monks is especially sad.

This is such a sad story about monopoly capitalism and plain old greed driving Sygma and the great tradition of French photojournalism into the ground. I was in France, looking for images to illustrate an article, when I learned that Sygma had been declared bankrupt. I didn’t know what was going on, and the deed seemed fishy. Now Don North has done me and the rest of us a great service of bringing the story to light. Three cheers for North and Consortiumnews.com. We need the journalism they’re doing, and we need it badly.