Today’s holiday culture wars continue an ancient struggle, as Nat Parry explores in this adaptation from his book, How Christmas Became Christmas: The Pagan and Christian Origins of the Beloved Holiday.

A representation of Father Christmas with a wassail bowl. (Public domain)

By focusing their wrath on what they perceive as “creeping secularism,” and making indignant claims about liberals and multiculturalists waging a “War on Christmas,” what U.S. culture warriors are doing — even if unconsciously — is implicitly conceding the inability of Christianity to fully establish itself as the dominant and overriding force in society.

In our modern-day discourse, this is largely cast as a debate over religiosity vs. secularism, but its history goes back to the process of Europe’s Christianization and the suppression of pagan religions in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages.

Ever since the adoption of Christianity as Rome’s official religion in 322 CE, the Church systematically attempted to suppress heathen gods, beliefs and customs, or to incorporate and adapt them into its catechism, all while attempting to whitewash their pagan origins.

In 336, the Roman Church declared Jesus’s birthday as Dec. 25, and 14 years later, in 350, the date was declared a nativity celebration. There is ongoing debate over why Dec. 25 was chosen as the date of Jesus’s birth, with some Christian historians continuing to insist that it was chosen for purely ecclesiastical reasons, but the fact is, the date cannot be found in the Gospels or other historical records, and, indeed, clues from the Bible actually undermine the claim that Jesus was born in late December.

Icon depicting Emperor Constantine, who converted the Roman Empire to Christianity in the early fourth century, accompanied by the bishops of the First Council of Nicaea. Artist: unknown. (Public domain)

In the nativity story in the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, Joseph and the very pregnant Mary make the treacherous journey from Nazareth to Bethlehem in order to register in a census, but if this is true, it most likely would not have happened in December, because Roman authorities didn’t take censuses during winter. This was due to the fact that temperatures often dropped below freezing and roads were in poor condition at this time of year.

Scholars have also pointed out that since December is cold and rainy in Judea, the shepherds probably would have sought shelter for their animals rather than “keeping watch over their flocks by night,” as written in Luke’s Gospel.

As archaeologist and biblical scholar Jim Fleming has noted, shepherds’ flocks may not have even been permitted on fields after they were plowed in October or November to allow the winter rains to soak into the parched ground. Shepherds were encouraged to graze their sheep before autumn to eat the stubble of sown crops and fertilize the fields, suggesting that — if the account in the Gospel of Luke is any guide — Jesus was probably born in summer or early fall.

This panel from a Roman sarcophagus, dating from the fourth century, depicts the Adoration of the Magi. It is located in the cemetery of St. Agnes in Rome. Courtesy of the Museo Pio Christiano, former museum of Benedict XIV. (Public domain)

With these clues in the Gospels, it must be asked, why would the early Church set the date of the nativity on Dec. 25? While some Christian scholars suggest that the date was chosen based on reasoning that identified the spring equinox as the date of the creation of the world and March 25 coinciding with both the day that light was created and the day of Jesus’s conception (with his birth following nine months later), this theory requires the suspension of critical thinking.

It not only ignores the clues offered in the Gospels but also disregards the fact that Dec. 25 happened to coincide with popular Roman holidays Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, Saturnalia and Kalends, from which many of our Christmas traditions are derived.

Days of Respite

In the highly stratified society of ancient Rome, the slaves and plebeians forgot their troubles by savoring the many days of respite offered by the ruling class. It has been estimated that there were over 100 days a year set aside for holidays and religious festivals, which helped to keep the mob mollified and to prevent trouble from erupting.

The most popular of these holidays was Saturnalia, which is said to be derived from older farming-related rituals of midwinter. Originally a celebration of the bounty of the harvest while pacifying the darkness of winter with revelries and games, Saturnalia was marked beginning on Dec. 17 with several days of celebration. For the period of festivities, criminals could not be convicted, nor wars started, and Roman social norms were turned on their head, with a good deal of intoxication and general irreverence on full display.

It was a time when “[l]icence is given to the general merrymaking,” when “the whole mob has let itself go in pleasures” and “is drunk and vomiting,” according to Seneca the Younger, a Roman philosopher, in his Moral Letters to Lucilius written in the mid-first century.

A feast, often lasting two or three days, was central to the celebration, with a variety of status inversion practices marking a temporary departure from social norms: masters would dine with their slaves, slaves would dine first after masters served them meals, the children of the house would entertain the slaves, and gender roles were sometimes swapped.

This 19th century oil painting by Roberto Bompiani illustrates a Roman feast, conveying their opulence and extravagance. (Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Open Content Program)

A mock “king” was chosen among friends, known as the “Lord of Misrule,” to lead in pranks, mischief, and merrymaking. As Lucian of Samosata wrote in the second century:

“[T]he serious is barred; no business allowed. Drinking and being drunk, noise and games and dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of tremulous hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water — such are the functions.”

During the celebration, slaves had freedoms that otherwise were denied to them the rest of the year, including the liberty to speak freely and rebuke their masters with impunity. Freed from the decorum and deference to their social betters that they were otherwise expected to show at all times, slaves enjoyed their time playing games, gambling, eating and drinking.

Besides partying, this was also a time for worshipping Saturn, the god of seed-sowing and wealth. Possibly a version of the Greek god Kronos as well as the Punic deity Baal, Saturn was thought to have ruled when the world enjoyed a Golden Age of prosperity and was believed to have taught important agricultural skills to men.

Please Make Your Tax-Deductible DONATION Today

Saturn was the husband of Ops, the Roman goddess of sowing and harvest, and the father of Jupiter, the god of the sky and thunder. Saturn’s reign was considered a period of equality and universal happiness without sorrow, a time when neither slavery nor private property existed, until he was betrayed by Jupiter and deposed. But during the Saturnalia festival, Saturn was again king.

This 16th -century engraving by Johannes Sadeler depicts Saturn presiding over his golden age. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Mary Stansbury Ruiz bequest)

Saturnalia coincided with other observances around the same time: the celebration of the solstice, Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, Opalia, and Kalends, which marked the beginning of the new year. Occurring one after another, the holidays generally merged together and it may have been difficult to say when one ended and the other began.

Meaning “the birthday of the Unconquered Sun,” Dies Natalis Solis Invicti celebrated both the sun god and the winter solstice — in which the sun stops moving south, when it was believed to “die,” and then “returned to life” when it begins its journey north again.

Sun of Righteousness

Early Church leaders were preoccupied with these pagan traditions and were anxious about how heathen holidays could provide an obstacle towards building the Christian faith. Tertullian, a prolific Christian author who advanced the notion that Jesus was born on Dec. 25, lamented in 230 — a century before the first official Christmas observance — that the pagans’ adherence to their traditions contrasted markedly with the lack of similar devotion demonstrated by the Christian faithful.

“By us, to whom Sabbaths are strange,” he wrote,

“and the new moons and festivals formerly beloved by God, the Saturnalia and New Year’s and Midwinter’s festivals and Matronalia are frequented, presents come and go, New Year’s gifts, games join their noise, banquets join their din! Oh better fidelity of the nations to their own sect, which claims no solemnity of the Christians for itself! Not the Lord’s day, not Pentecost, even if they had known them, would they have shared with us; for they would fear lest they should seem to be Christians.”

These concerns, openly expressed by early Church leaders regarding the popularity of heathen festivals, indicate that there was a strong motive to replace pagan festivals with Christian ones.

A sermon by early Church Father John Chrysostom, entitled, “On the solstice and equinox of the conception and birth of Our Lord Jesus Christ and John the Baptist,” also provided a hint of the threat to Christian doctrines posed by the Roman holiday of Dies Natalis Solis Invicti.

“They also call this the birthday of the invincible one (Invictus),” fretted Chrysostom. “But who then is as invincible as our lord who defeated the death he suffered? And if they say that this is the birthday of the sun, well He Himself is the Sun of Righteousness.”

Jesus depicted as the sun is a common motif in Christian art. In this artwork, from late 15th-century Germany, the Christ child and Virgin Mary are surrounded by billowing rays of sun. “The Crowned Virgin and Child as The Apocalyptic Woman Clothed in the Sun.” Artist: unknown. Germany, late 15th century. (Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Open Content Program)

As these accounts make clear, there is no doubt that the early Church leaders who designated Dec. 25 as Christ’s nativity were fully aware of this day’s significance in the cult of Sol Invictus, and were generally concerned with the popularity of Roman pagan customs such as Saturnalia. As Steven Hijmans, a professor of Roman art and archaeology, has asked, “the question is whether they chose it because of or despite that pagan significance.”

But what it also makes clear is that the sun played a major role not only in pagan beliefs, but also in the Christian faith. There are at least 80 references to the sun contained in the Bible, both in the Old Testament and New, and Jesus himself was identified as the Sun of Righteousness.

Therefore, as the 20th-century theologian Frank Homer Curtiss has explained, “since Jesus is the spiritual Lightbringer or the manifestation of the Spiritual Sun to humanity, the day of his birth should very properly be celebrated on the solar date of the Sun’s birth, as was the case with all previous Lightbringers.”

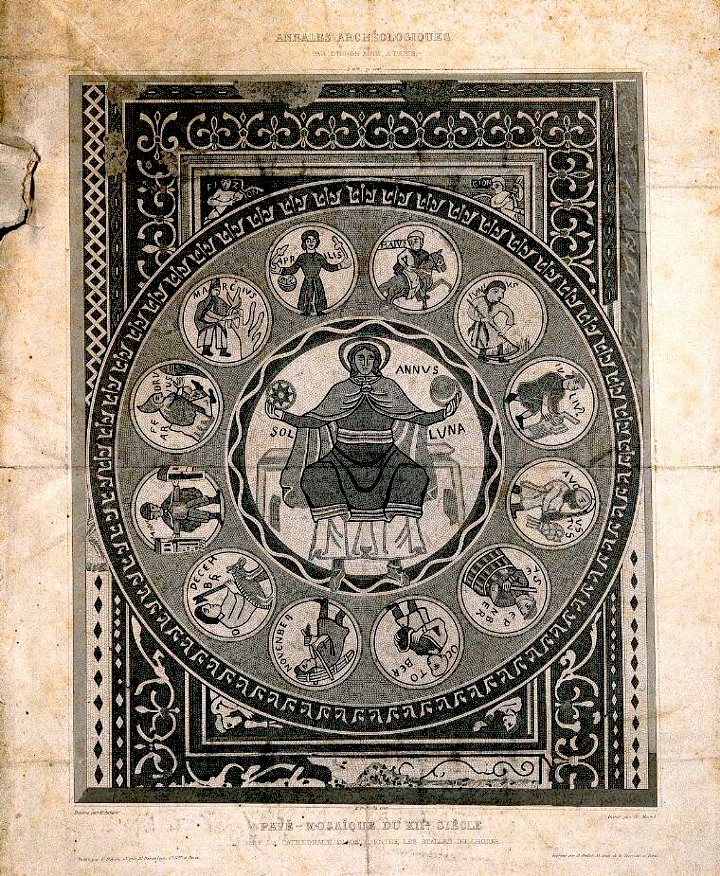

This etching represents a mosaic from the Santa Maria Assunta Cathedral in Aoste, Italy, depicting the months of the year. In the center is a figure labelled “Annus,” or “year,” holding two spheres marked “Sol” and “Luna,” or “sun,” and “moon.” The yearly cycle is depicted as circular and marked by anthropomorphized months. Etching by C. Martel after E. Aubert. (Courtesy of the Wellcome Collection)

Believed to influence the growth of crops and to govern human affairs, the sun, moon, planets and stars were studied with great care by the ancients. The sun was revered as both a cosmic body and as a god, which could explain why both paganism and Christianity attached importance to celestial events such as the equinox and solstice, offering some context both for pagans’ solstice celebrations and the calculations of early Church leaders regarding Jesus’s birthday.

In this sense, the beliefs of polytheists and Christians were not actually so diametrically opposed, and therefore the nature of supplanting paganism with Christianity might be better understood as a natural evolution than a hostile takeover.

The sun’s symbolic significance and its actual importance as the giver of life is why it has been celebrated by so many different religions, and ultimately why early Christian writers attributed prominence to the spring equinox as the time of Jesus’s divine conception and the winter solstice as the time of his birth.

Particularly in pre-industrial (and pre-electrical) societies, during the darkest time of the year, many happily joined in the celebration of the Old Testament’s prophecy of the coming of the Sun of Righteousness, as brought to mind in the popular English carol “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.”

Recalling the prophecy of Malachi, with its admonition that “for you who fear my name, the Sun of Righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings,” “Hark!” includes the lines, “Hail the Sun of Righteousness! Light and life to all He brings.”

Christmas in a Pagan World

While Saturnalia is most commonly cited as the main precursor for the Christmas celebration, this Roman holiday was just one of the midwinter celebrations that Christmas would have to compete with as the Christianization of Europe began to take shape in the first millennium.

Christmas, like Christianity itself, developed within a pagan world, and as the shortest day and longest night of the year, the solstice has long symbolized the sun’s rebirth from the womb of darkness. It has been recognized in various ancient cultures as Hökunótt, Lucina, Lenacea, Zurram, Dongzhì Festival, Inti Raymi, Soyal, Shab-e Yalda and Yule.

This coin, from c. 300–295 BCE, depicts Poseidon hurling a trident. Many scholars believe that the legends of St. Nicholas served as a replacement during the Christianization period for pagan legends of Poseidon. c. 300–295 BCE. Silver. (Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art’s Open Access initiative)

In ancient Greece, the sea god Poseidon was celebrated around the time of the winter solstice, while in the tradition of Modranicht, Old English for “Night of the Mothers,” Anglo-Saxon pagans would celebrate on what is now Christmas Eve by offering sacrifices to the gods.

Modranicht was also observed in southern Denmark, as the scholar Venerable Bede recorded, noting that on Dec. 25, “when we celebrate the birth of the Lord … they used to call the heathen word Modranecht, that is ‘mother’s night,’ because (we suspect) of the ceremonies they enacted that night.”

An important Slavic festival at the winter solstice, which later became associated with Christmas, was called Božic, simply meaning “little god.” The festival celebrated the birth of a new god of the sun (a little god) to replace the old and weakened solar deity during the longest night of the year.

It was in this context of long-established customs, rituals and holidays that Christmas developed, absorbing various belief systems that in important respects stood in marked contrast to Christian teachings.

While Christians believed, for example, that God considers gluttony and lust as sins that could prevent one from achieving salvation, Nordic pagans believed that their deities, known as Æsir, were delighted by boisterous feasts where alcohol flowed freely. As explained in The Viking Gods, “Happy gatherings at the banquet, where the flowing mead-horn was passed freely round, and where words of wisdom and wit abounded, or martial games with sharp swords and spears, were the delight of the Æsir.”

Yule’s Post-Pagan Evolution

Churches decided that the nativity deserved a preparatory period like Easter’s Lent, and so in the late fourth century, they initiated Advent, first in northern Italy and then in Rome. Advent had been proposed by church leaders at the council of Saragossa, Spain, in 380, when they defined a 21-day period of fasting beginning on Dec. 17, which of course, also happened to be the first day of the Saturnalia festival.

It was also in the year 380 that Emperor Theodosius I signed a decree that punished the practice of pagan rituals. As the Western churches elevated Dec. 25 over Jan. 6 (the date observed as Jesus’s baptism), they launched the Midnight Mass tradition, the first of three separate Christmas masses, traditionally beginning at midnight when Christmas Eve gives way to Christmas Day.

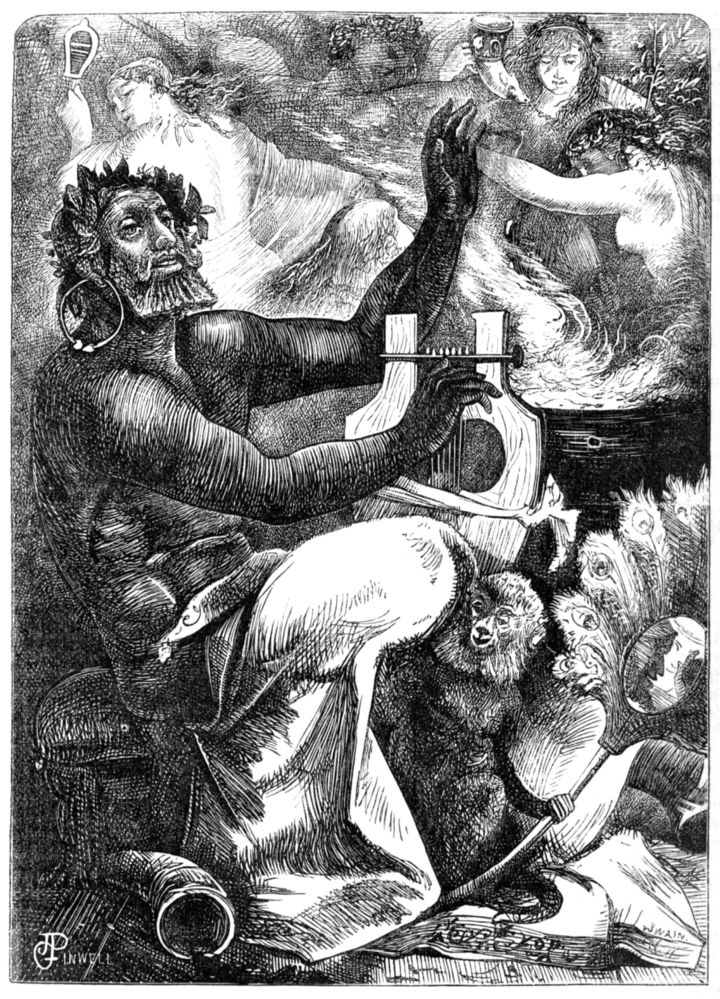

This engraving was an illustration for the poem “The Saturnalia” by Walter Thornbury, appearing in Once a Week magazine in 1863. Artist: George John Pinwell, engraved by Joseph Swain. (Courtesy of Internet Archive. Public domain)

But while conversion was well underway in southern Europe, further to the north, people continued to recognize the old gods. Although Christianity had spread to Britain by the fifth century, it would take another five or six hundred years to come to Slavic lands and six or seven hundred years for the religion to establish itself the Nordic countries. Scandinavia’s neighbors to the south — the Frisians and the Saxons — converted in the 700s and 800s, while Poland and Kievan Rus became officially Christian in 966 and 988, respectively.

Denmark officially adopted Christianity in the late 900s, Norway in the early 11th century, and Sweden adopted Christianity very gradually, finally converting in the late 12th century. The missionaries who brought Christianity to the pagan tribes also introduced the celebration of Christmas.

It came to Ireland through Saint Patrick in the late 400s, to England through Saint Augustine of Canterbury in the early 600s, and to Germany through Saint Boniface in the mid-700s. The Scandinavians received it through Saint Ansgar in the 860s.

But even as conversion took place, there was much overlapping of the old and new religions while Christmas developed as one of the most important holidays on the Christian calendar.

In Denmark, the pagan solstice celebration became a Christian Christmas feast around the year 1000, nearly 700 years after it was established in Rome. As described in the book The Family’s High Times in Olden Days, the Danish Church ordered that the birth of Jesus should be celebrated on Dec. 25 and tried to have the ancient name of Yule changed to Christ Mass. Danes rejected the name change and stuck with Yule, which is still the name used to this day.

Through the Middle Ages, the celebration continued to combine pagan and Catholic customs, with Christmas Eve generally observed as a quiet vigil ending with the Catholic Midnight Mass. But the following days were largely spent on drinking parties, wild games, dancing and fights. “Drinking Christmas,” or drikke jul in Danish, was the Viking Age expression to celebrate Christmas and was commonly used all the way up until the 16th century.

The pagan-influenced festivities were so wild that the Church had to issue laws that prohibited raucous celebrations during the Christmas days. After Denmark became the seat of an independent province of Scandinavia in the early 12th century, the Church issued one of its earliest ordinances, which was to command absolute peace and quiet from Dec. 25 to Jan. 6.

Indeed, laws adopted across Scandinavia during the Middle Ages declared a “Christmas peace” that began in the days leading up to Christmas and continued for weeks after the holiday.

While the name “Christmas” was rejected in Denmark, it was adopted in Britain in the early 11th century. Cristesmæsse, as it was called in Old English, evolved as Christendom was establishing itself as Europe’s political and social order, absorbing and suppressing heathen practices as the Christian faith spread across the continent.

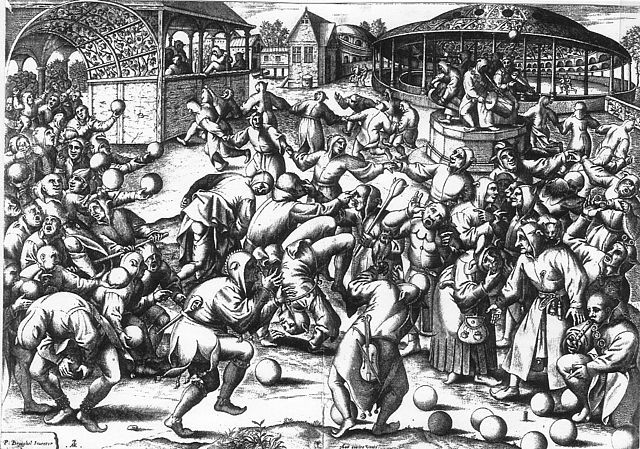

This 16th-century engraving depicts characters dancing, playing music and participating in a bowling game. It is generally seen as an indictment of the folly and misrule associated with the Christmas-related Feast of Fools. Artist: Pieter Breugel. (Public domain)

But Christianity, as a foreign religion that aimed to replace time-honored gods who were revered and loved, was not universally embraced. Pagan gods and their worship were integral to the people’s traditions and customs, with roots in local languages and hallowed by antiquity.

The adoption of Christianity, therefore, was a very slow process, with much overlap between the old beliefs and the new. These old beliefs were influenced by the new one — as well as by each other — even as they influenced Christianity’s development.

There was a constant flow of information and views of the world, and it is likely that Roman and Greek gods may have filtered into the Norse pantheon, along with some customs relating to the celebration of the winter solstice. As the German medieval chronicler Adam of Bremen described his visit to the temple of Uppsala in central Sweden, the gods worshipped by the Vikings bore striking resemblance to more familiar Roman gods. Odin, in particular, was depicted “as our people depict Mars,” Adam notes, while Thor resembled the Roman god Jupiter.

As gods of agriculture, prosperity, life and fertility, the Norse Freyr and Roman Bacchus (the son of Jupiter and grandson of Saturn) also shared much in common.

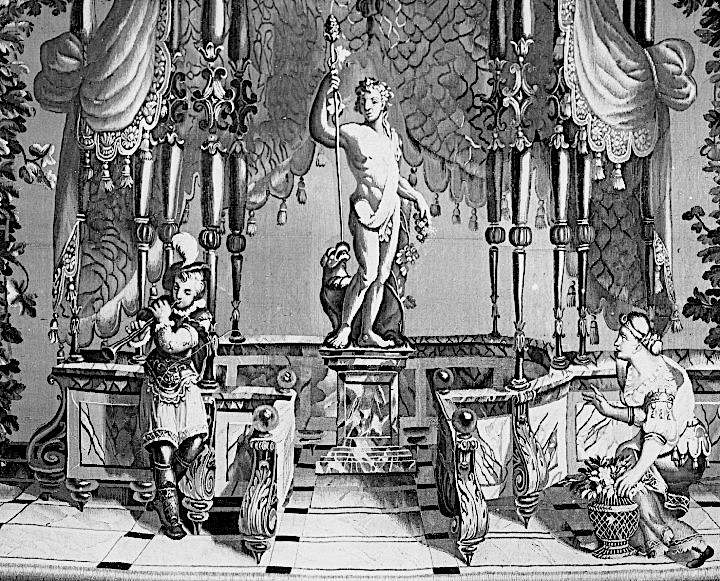

This image depicts Bacchus and his leopard on a pedestal, with a man playing a pipe and a woman crouching before a basket. “Offering to Bacchus” detail, c. 1688–1711. Artist: Bérain, Jean — the Elder. (Courtesy of the J. Paul Getty Museum’s Open Content Program)

With this traditional blending of faiths in mind, Christian missionaries learned to employ a variety of strategies in convincing pagans to adopt the new faith. Creative forms of persuasion were developed, including the publication of an epic poem called the Heliand in the first half of the ninth century.

Meaning “savior” in Old Saxon, the Heliand was written to overcome Saxon ambivalence toward Christianity. It adapts the story of Jesus to fit the worldview of the pagans, making the New Testament relatable by providing recognizable parallels to Teutonic mythology and Germanic culture, depicting Jesus more as a wise chieftain than a divine teacher.

His 12 apostles are presented as loyal vassals who fight to defend their lord from his enemies, the disciples have distinctly Germanic virtues and are rewarded by Jesus with arm bands, and the Feast of Herod is recast as a drinking bout.

In a retelling of the nativity story, the Heliand describes the message of “Mighty God’s angel” to the shepherds (who are depicted as watching over horses rather than sheep):

Then he spoke and said there would come a wise king,

magnificent and mighty, to this middle realm;

he would be of the best birth; he said that he would be the Son of God,

he said that he would rule this world,

earth and sky, always and forevermore.

He said that on the same day on which the mother gave birth to the Blessed One

in this middle realm, in the East,

he said, there would shine forth a brilliant light in the sky, one such as we never had before between heaven and earth nor anywhere else,

never such a baby and never such a beacon.

Around the same time that the Heliand was written, the Stuttgart Psalter was published. Depicting the Book of Psalms in pictorial form, the Stuttgart Psalter offered a wide array of monsters, unicorns, animals, and allegorical figures. Much like the Heliand, this collection of illustrations helped establish an image of Jesus as an all-powerful warrior, slaying beasts such as dragons and lions.

With these creative adaptations of the Bible, the Saxons were introduced to Christianity in a way they could relate to, and these more pagan-friendly versions of Scripture soon spread to neighboring regions.

Stuttgart Psalter image depicting Christ as a heroic warrior. Illustration from Psalm 91, verse 13, circa 820–830. (Courtesy of Württembergischen Landesbibliothek Stuttgart. Public domain)

As popes and missionaries attempted to suppress pagan traditions and absorb new peoples into the faith, renaming festivals and giving them a veneer of Christian respectability was considered more effective — and more feasible — than total eradication.

Elements of heathen practices were sanctified by some cultures in a process called syncretism, or the combining of different beliefs. Known by its Latin name Interpretatio christiana, it was a strategy advocated by early popes to incorporate pagan lore into Christianity. As Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) declared: “Do not kill the heathens — just convert them; do not cut their holy trees — consecrate them to Jesus Christ.”

This is what happened in Norway, when King Haakon I, ruler of Norway from 934 to 961, scheduled ancient celebrations of Yule to coincide with Christian celebrations. A baptized Christian, Haakon issued a decree that Yule celebrations were to take place at the same time as the Christians celebrated the birth of Christ, “and at that time everyone was to have ale for the celebration with a measure of grain, or else pay fines, and had to keep the holiday while the ale lasted.” In other words, everyone had to drink beer in honor of baby Jesus or they were slapped with a fine.

One of Haakon’s successors, Olafur Tryggvason, who ruled Norway from 995 to 1000, continued these practices by removing heathen sacrifices known as blot and drinking connected with the sacrifices, and instead convinced the common people to take up festive drinking at Christmas, Easter, St John’s Eve and Michaelsmas.

Magic & Misrule

Competing against belief systems that used human sacrifices to satisfy powerful and fickle gods, Church leaders were also preoccupied with demonstrating that Christian rituals were at least as effective as heathen practices, and that Christianity would triumphantly lead its followers to glory in this world and the next.

To do so, religious leaders devised new and elaborate ways to observe the nativity in order to demonstrate the majesty of Jesus. In the ninth century, churches began adding extra dialogues and songs to Christmas services to celebrate the birth of Christ in a practice called “troping,” which entailed half the church choir singing a question and then the other half responding.

In time, this practice led to dramatization and eventually to the presentation of nativity plays prominently featuring the magi and King Herod. A play that became popular in church services was The Prophets, in which a priest conducted a dialogue with various prophets such as Jeremiah, Daniel and Moses and choir boys played bit parts like a donkey or devil.

Other popular medieval Christmas plays dealt with subjects such as the Creation, Fall, and the End Times, and all the plays featured devils, including Lucifer himself. In a 13th-century Bavarian Christmas play, there was a scene featuring demons hauling King Herod to hell, and in another scene, Lucifer mocks the shepherds at the nativity, claiming the good tidings of the angels are lies.

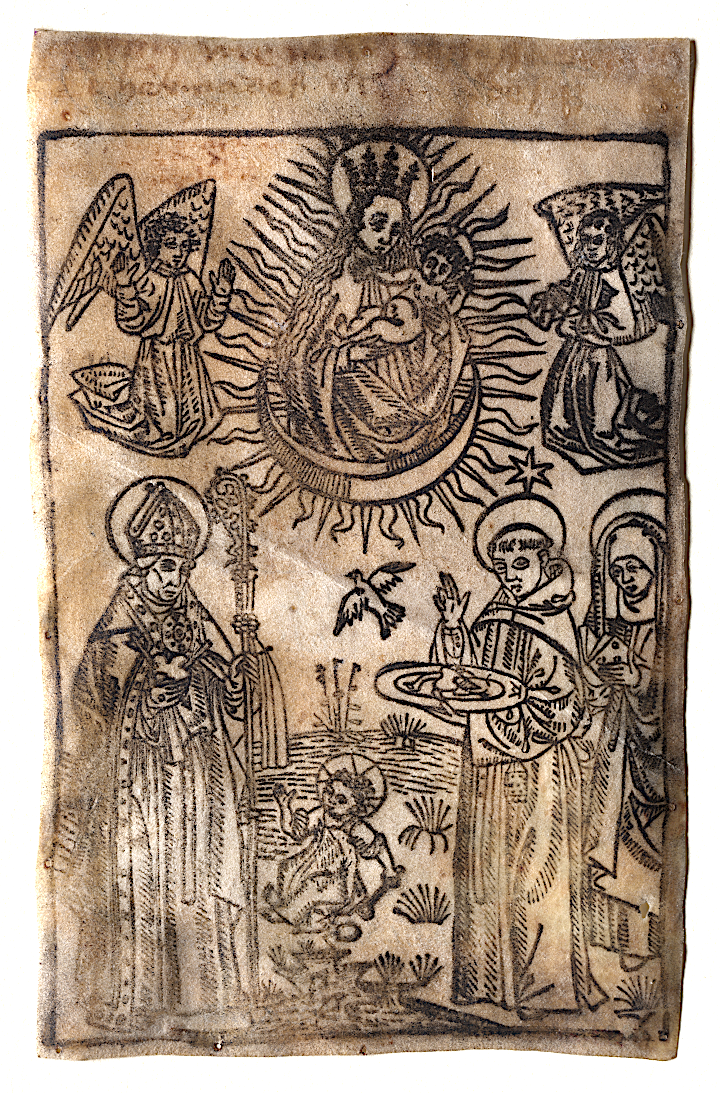

This woodcut from 15th-century Germany depicts the Virgin Mary, baby Jesus, angels and several saints. During the Middle Ages, traditional folk magic increasingly became viewed as heretical and was associated with the Devil, while the miracles of saints and “angel magic” grew in both popularity and legitimacy. (Courtesy of Cleveland Museum of Art’s Open Access program)

The medieval Church took great pains to emphasize the solemn nature of the nativity and the need to observe it sedately but ultimately couldn’t change the fact that the celebration took place in a historical and cultural context that had as much to do with living in an agricultural society dominated by seasonal realities as it did with religious beliefs.

The farmers’ crops had been harvested and most work was done by this time, and it just so happened that this was when the year’s supply of beer and wine was ready to drink, so it was widely considered a good time to indulge.

Basically, December was a month to blow off steam, and regardless of what God or gods people worshipped, it was bound to be a time of merrymaking which could easily degenerate into rowdiness and disorder.

Sometimes the traditions of religiosity and misrule mixed, with pious observances tainted by raucous disorder. Sedate Midnight Mass services, for example, were often disturbed by drunken revelers who seemed to think that the late-night events were just another opportunity for mayhem.

In the Rhineland of Germany, Midnight Mass had to be suspended in the 18th century because people tended to view them as just part of their Christmas merrymaking rather than as sacred functions. As described in Christmas Customs and Traditions, the congregation at a typical Midnight Mass resembled “a crowd of wild drunken sailors in a tavern” where “the only sober man was the preacher.”

As Christianity reached rural areas, farmers gladly accepted baptism and welcomed new holidays such as Christmas, but they still persisted in performing ancient rites and participating in old pagan cults. This was the case even after the ancient deities and myths upon which they were based had been completely forgotten. To the peasants, Christianity was not a replacement of their mythology, but rather an addition to it.

“Christianity may have offered a hope of salvation, and of blissful afterlife in the next world, but for survival in this world, for yearly harvest and protection of cattle, the old religious system with its fertility rites, its protective deities, and its household spirits was taken to be necessary,” writes scholar Liliana Damaschin.

“This was a problem the Christian church never really solved; at best, it could offer a Christian saint or martyr to replace the pagan deity of a certain cult, but the cult itself thrived, as did the mythological view of the world through which natural phenomena were explained.”

This photo of vintage Christmas card features mistletoe, holly and bells, all of which were believed to hold magical properties in pagan beliefs. Evergreens such as holly and mistletoe were used as sacraments to ensure growth and fertility, while bells were used to frighten off spirits. Artist: Ellen Clapsaddle, from the personal collection of Nancy Oram. (Permission granted to use freely. https://discover.hubpages.com/holidays/vintagechristmasimages)

This is why many customs from pre-Christian times have become ubiquitous — notably the use of evergreens such as holly, mistletoe and trees, as well as the Santa Claus legend, which is actually an amalgamation of ecclesiastical and pagan myths, reimagined by writers, artists, and marketers to reflect contemporary realities and values.

With an appreciation for how these magical traits of Christmas date back to ancient times when belief in the supernatural was widespread, it begins to make sense how “Christmas magic” continues to be such an enduring theme in popular culture, undermining the insistence by modern-day culture warriors that the true “reason for the season” is Jesus’s nativity.

An examination of contemporary popular culture also belies the claim that Christmas is a fundamentally Christian tradition that originated from the birth of Jesus in or around the year zero and grew organically from there. At a popular crowdsourced website called Ranker, only one Christmas movie in a listing of more than a hundred bears any direct relation to the birth of Jesus. The Nativity Story, a 2006 epic biblical drama film based on the Gospels, comes in at No. 43 on Ranker’s list.

Far more popular are light-hearted fare such as 1989’s Christmas Vacation starring Chevy Chase, 2003’s Elf starring Will Ferrell, and 1990’s Home Alone starring Macaulay Culkin. Also doing well are romances such as 1954’s White Christmas and 2003’s Love Actually, as well as horrors such as 1984’s Gremlins and 2015’s Krampus, which both explore the darker side of Christmas.

Many of the most loved Christmas movies deal with themes that harken back to the holiday’s roots as a period of misrule and social inversion. A 1983 flic called Trading Places, for example, explores this theme with a story of a homeless man named Billy Ray Valentine (played by Eddie Murphy) and a Wall Street stockbroker named Louis Winthorpe III (played by Dan Aykroyd) switching roles, with the homeless man enjoying all the luxuries of being wealthy and the stockbroker enduring the indignities of poverty.

Home Alone adds its twist on this theme by telling the story of a young child who is accidentally left in charge of a household during the Christmas holiday, in a throwback to the tradition in ancient Rome of letting the lowliest member of the household serve as Lord of Misrule during the Saturnalia days.

Another film that celebrates Christmas as an opportunity for misrule is the R-rated Office Christmas Party starring Jennifer Anniston, which explores the tradition of raunchy parties as a well-known component of the holiday season.

At office Christmas parties there is often a loosening of the corporate hierarchy, with a sense of equality and comradery that may be absent in the office environment the rest of the year, which is another throwback to Saturnalia when slaves were permitted to speak their minds and rebuke their masters.

Christmas Critics

While considered by many an important component of the year-end festivities, alcohol-lubricated office parties have also been a dangerous opportunity for employees to make ill-advised sexual overtures toward their colleagues, resulting in increased infidelities at this time of year and often a flurry of divorces in January. In the 1950s, critics of the increasingly popular office parties in the United States alleged that they violated the sanctity of the nativity observance, endangered the moral values of family life, and encouraged improper behavior between the sexes.

While these mid-20th century critics may have thought that they were responding to a new and unwelcome development in the modern celebration of Christmas, they actually followed a long line of Christmas detractors who lamented its lascivious and sacrilegious side. Way back in the fifth century, Bishop Asterius of Amasea gave a sermon in railing against how the raucous Christmas/Saturnalia festival “render[ed] the city a place to be shunned rather than visited.”

This reality continued over the centuries to be a source of friction between the more pious religious elements and those who see the holidays as a winter carnival, a chance to let their hair down and gorge themselves on food and drink. None of this debauchery is particularly Christian in nature, of course, with admonitions in the Bible warning against gluttony and immodesty.

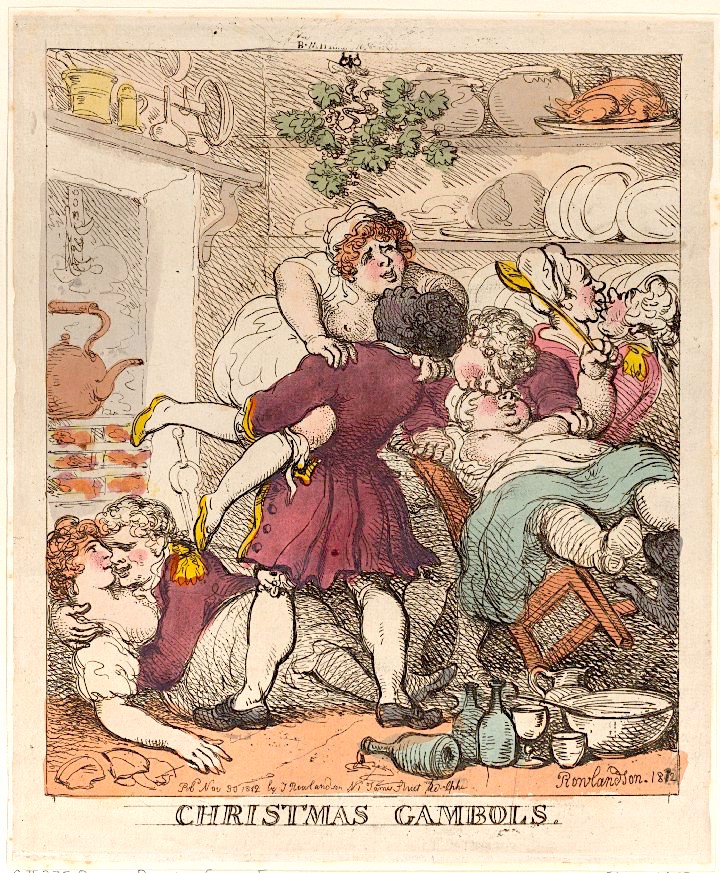

The scene in this 1812 illustration depicts some rather lascivious holiday festivities, with mistletoe overhead and four couples embracing, kissing, or attempting to kiss below. Artist: Thomas Rowlandson. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Open Access program; The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959)

Proverbs 23:20, for example, advises:

“Do not join those who drink too much wine or gorge themselves on meat, for drunkards and gluttons become poor, and drowsiness clothes them in rags.”

Another useful warning from the Bible is Ephesians 5:18: “Do not get drunk on wine, which leads to debauchery. Instead, be filled with the Spirit.”

With these teachings generally thrown out the window during the Yuletide celebrations, a 16th-century Anglican bishop regretted that “[m]en dishonour Christ more in the 12 days of Christmas, than in all the 12 months besides.”

Paganism-Purging Puritans

The Puritans, who arose as a religious movement in the late 16th century in an effort to “purify” the Church of England by eliminating remnants of the Roman Catholic “popery” that had stayed in place following the end of the English Reformation, launched a campaign to purge the relics of paganism, including Christmas, that the early Church had incorporated into its liturgy, convinced that these compromises with heathens had weakened the Christian faith and allowed forces of the Devil to wield influence over Christians.

In 1644 the Puritan-led English Parliament published an “Ordinance for the better observation of the Feast of the Nativity of Christ,” emphasizing that the Christmas celebration, as widely observed, was “contrary to the life which Christ himself led here upon earth, and to the spiritual life of Christ in our souls.”

Therefore, Parliament declared “that this day particularly is to be kept with the more solemn humiliation because it may call to remembrance our sins and the sins of our forefathers, who have turned against this Feast, pretending the memory of Christ, into an extreme forgetfulness of him, by giving liberty to carnal and sensual delights.”

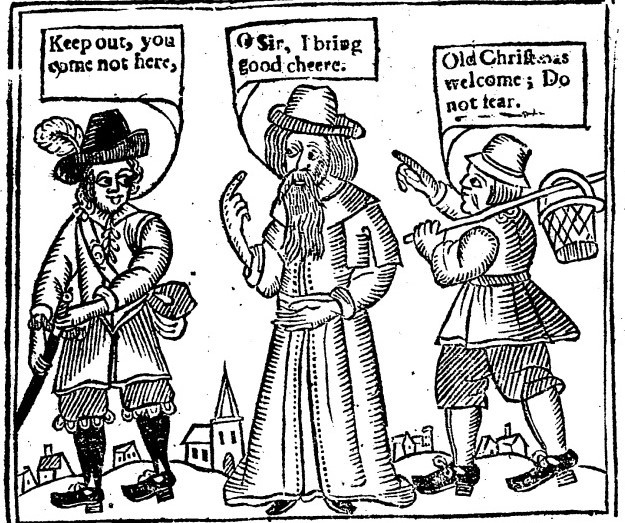

In this cartoon, the man on the left, presumably a Puritan, tells Father Christmas, “Keep out, you come not here.” Father Christmas responds, “O Sir, I bring good cheere.” The passerby on the right says, “Old Christmas welcome; Do not fear.” Frontispiece to John Taylor’s pamphlet The Vindication of Christmas, printed 1653. (Public domain)

Across the pond, the American Puritans would follow suit with a ban on Christmas initiated in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1659. According to a public notice posted that year, “the exchanging of Gifts and Greetings, dressing in Fine Clothing, Feasting and similar Satanical Practices are hereby FORBIDDEN.”

The case that the Puritans made for prohibiting the Christmas celebration included specific references to the holiday’s pagan roots. As Puritan Reverend Increase Mather of Boston observed in 1687,

“the early Christians who first observed the Nativity on Dec. 25 did not do so thinking that Christ was born in that Month, but because the Heathens’ Saturnalia was at that time kept in Rome, and they were willing to have those Pagan Holidays metamorphosed into Christian ones.”

From Pagan to Secular

The efforts of the Puritans to suppress Christmas in the 17th century were a recognition not only of its pagan origins but the inability of the Church to rein in its hedonistic tendencies. Many of the “secular” aspects of Christmas that evangelicals and culture warriors now criticize are in fact survivals of these pagan traditions, albeit stripped of their original meaning.

The ecclesiastical elements of Christmas, on the other hand, are impositions on these more ancient celebrations. While the Christian contributions have over time taken on the appearance of long-held religious traditions, for example the practice of singing at manger displays or attending Midnight Mass, there once was a time when these were novel additions to the end-of-year winter solstice celebrations that took place across Europe.

Therefore, when people complain about a manger scene being removed from public grounds, or when Tim Allen grumbles about saying “Merry Christmas” being “problematic,” they are not really defending the true “reason for the season” — what they are doing is engaging in a very long-running battle to supplant the original reason for the season (the celebration of the return of the sun) with a religious element that has no basis in historical reality, i.e. the birth of Jesus Christ, which almost certainly did not take place on Dec. 25.

Although the conflict over the meaning of Christmas appears to be focused more today on a struggle between Christian and secular forces, which has played out largely as a polarized cultural battle over “religious freedom” and “creeping secularism,” what the annual Christmas controversies really are is a continuation of an ancient struggle to suppress heathen gods, beliefs and customs.

Photo of billboard proclaiming “Keep Christ in Christmas” in New Jersey, Dec. 20, 2005. (Jackie “Sister72,” Flickr, CC BY-ND 2.0)

Perpetuating these sorts of myths and falsehoods can have palpable effects on society, with the ignorance of history easily exploited by powerful interests to highlight dividing lines for political purposes.

The rewriting of Christmas history to fit a certain narrative is similar to the way that history textbooks give credit to Christopher Columbus as the first explorer to ever stumble upon the “New World,” glossing over the fact that it had already been settled by peoples who had migrated on foot from Asia thousands of years earlier, and entirely ignoring the fact that Columbus’s voyage was not even the second to “find” America.

By omitting evidence that Viking, Irish and African explorers had in fact found it hundreds of years before Columbus set sail, the textbooks give students a frankly erroneous account of the New World’s discovery.

Likewise, children are given an inaccurate view of history when they are told that “the first Christmas” took place when three wise men travelled from the east to bring gifts to a newborn baby named Jesus.

Assuming that this biblical story happened as the Gospels claim, it probably wasn’t at the end of December and therefore it cannot be considered the first Christmas — especially considering the fact that the Church didn’t declare the holiday until three and a half centuries later.

Deciding whether to say “Merry Christmas” or “Happy Holidays” is part and parcel of this centuries-old process of Christianizing the midwinter celebration. Regrettably, these days, neither “Happy Holidays” nor “Merry Christmas” serves the traditional function of what linguists call “phatic speech.”

These are expressions that are intended to establish and maintain good social relations, greetings such as “hello” and “nice to see you,” which signal the speaker’s goodwill and puts people at ease without necessarily communicating any information. In contrast, the choice between using “Merry Christmas” and “Happy Holidays” is fraught with difficulties and one’s choice could be seen as a signal of political ideology rather than friendliness.

This dilemma — as exemplified in Tim Allen’s politically charged line in The Santa Clauses series — has led to a good deal of anxiety during the holidays, which is unfortunate because Christmas can already be stressful enough.

It also detracts from the sense of unity and celebration that should be at the core of the holiday, especially considering the fact that nine out of ten Americans celebrate it and most don’t particularly care whether they are greeted with “Happy Holidays” or “Merry Christmas.”

Celebrating Christmas should not be so politicized and one’s choice of words in greeting others shouldn’t be seen as an indication of ideological allegiance, so perhaps the best thing to do is just say both as a way to subvert the assumption that this contrived controversy is even grounded in reality to begin with — because it’s not.

Nat Parry is the author of the recently published book How Christmas Became Christmas: The Pagan and Christian Origins of the Beloved Holiday, from which this article has been adapted.

This article is from Nat Parry on Medium.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please DONATE to CN’S Winter Fund Drive

Strange not to have included a discussion of Mithras and the many coincidences between Mithric and Christian mythology.

Also strange that an ancient coin that reads Demetriou basileos is captioned: “This coin, from c. 300–295 BCE, depicts Poseidon hurling a trident. Many scholars believe that the legends of St. Nicholas served as a replacement during the Christianization period for pagan legends of Poseidon.”

Demetrios is neither Poseidon nor St. Nicholas & seems irrelevant to the subject.

Enough of all these fairy tales!

It is too bad that Parry omits the most apparent source of “Christmas”, Mithraism. It was pro9bably Christanity’s main rival as a new religion spreading through the Roman Empire. And according to its teachings, Mitrhas was born in a cave at the winter solstice to save the world ….

I too loved reading this. So much history to unwind. Still so relevant today. I have long boycotted the commercial consumer aspect of xmas but this article helps me see that the solstice celebratory saturnalia side is worth maintaining some aspects of. The people pushing austere Jesus never lived by his teaching anyway. Thanks for the research!

The Forces of Darkness have achieved victory in the War on Christmas.

Christmas is cancelled this year, in both Bethlehem and Jerusalem. A huge victory in the War on Christmas!

Joe Biden says …. “I did that!”

you’ll hear more about that…. This will be a campaign theme for The Big Guy against the Donald, claiming that the Big Guy provided the Victory in the War on Christmas that the Donald could not deliver.

for surely, if there is a War on Christmas, then getting both Bethlehem and Jerusalem to cancel Christmas and turn their Nativity scenes into scenes of mourning for the many children in the rubble, then this has to be considered a major victory in the War on Christmas.

Great way to turn the massacre of Gaza into a war on Christmas event. Christian priests in the West Bank cancelled the traditional celebrations (not Christmas itself) for a solemn commemoration of those massacred. Nothing to do with Biden or US political machinations for a war on Christmas.

Great article, informative, funny, hilarious, entertaining and educating, mind broadening for open minded people.

And co-incidentally this article appeared yesterday:

Xxxx://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/24/nativity-style-statuettes-found-at-pompeii-suggest-pagan-ritual-experts-say

But those black and white etchings, woodcuts, engravings etc. made the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end; as if i was there in that time and it was awful.

These early beginnings of Christian traditions is not unknown to me and it is fascinating how the early Christians used existing pagan deities and customs to push their new religion on older societies. But I also know that Christians gave us the dark ages, by being opposed to learning of any kind, declaring that it was a sin to usurp God’s exclusive right to knowledge. They burned books and murdered writers and philosophers. Many works of Greek and Roman poets, playwrights, astronomers, and others were destroyed and the only reason we still have the works that survived is because of Muslim scholars who preserved them. It is fascinating to know how the rigidly divided religions of our times were once never so divided. Like nationalism, frozen religious doctrine is pernicious and dangerous.

Great article.

This year reveals the true nature of Capitalist Corporate Christmas.

With Christmas cancelled in Bethlehem, there is no longer the possibility of maintaining the pretense that the celebration is for the receipt of Tidings of Joy from Bethlehem telling us of the birth of the Prince of Peace. That did not happen this year. There are no Tidings of Joy from Bethlehem. Only calls of mourning for the dead.

So, we see Capitalist Corporate Christmas, now completely separated from any pretense of a relationship to Jesus Christ. Just crass commercialism, go out and shop. Go into debt for the good of the country and your bankers. Be herded onto climate destroying airliners by corporations that only want increased profits and lower costs. All because it is Corporate Christmas time, and these are the things you absolutely must do for every Capitalist Corporate Christmas.

Just don’t even think of saying the words “Peace on Earth”…. we have ways of dealing with anti-American ideas like that.

A splendid history! However, I would rather see ‘faith’ referred to as ‘adaptive belief systems’.