SPECIAL REPORT: David McBride appeared in a Canberra court earlier this month appealing his conviction in a case that could determine if a soldier’s duty is to serve only the King or also the public, reports Joe Lauria.

David McBride outside the Supreme Court in Canberra on Friday after pleading guilty to all charges. (Cathy Vogan/Consortium News)

By Joe Lauria

in Canberra, Australia

Special to Consortium News

A three-judge panel in the Australian capital is weighing an appeal by whistleblower David McBride that could determine if a soldier’s duty is to serve the public or only his superior officers even if it means covering up evidence of his nation’s war crimes.

The judges are also considering the question of whether Australian soldiers owe their allegiance to the British crown or to the people of Australia.

The three Court of Appeal judges have been deliberating for four weeks to determine if the trial judge erred in not permitting McBride a public interest defense. When classified evidence was removed from the courtroom during his trial, the former military lawyer was left with little choice but to plead guilty in November 2023 to breaching national security laws for leaking the war crimes story to the media.

In blocking his ability to tell a jury his motive, the trial judge then sentenced McBride to a harsh five years and eight months in prison, of which he’s served 11 months at the Alexander Maconochie Centre in the capital territory.

Looking fit, McBride appeared for his appeals hearing on March 3 in a Canberra courtroom to a standing ovation from his supporters who filled the public gallery. He motioned for calm when one said loudly amidst the applause, “It looks like there is a public interest in your case.”

Before court was called into session, a rally was held on the street outside.

Part of an Alarming Trend

McBride’s case comes as one more incidence in an increasing tide of repression in Western countries against whistleblowing and free speech.

WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange was the most prominent of these cases in the past five years until the U.S. understood it would lose its extradition case and struck a plea deal in which Assange admitted he broke an unconstitutional U.S. Espionage Act that conflicts with the First Amendment.

A British Terrorism Act has been used since October 2023 to detain and interrogate journalists for their criticism of Israel’s genocide in Gaza. Berlin police have raided meetings in support of Palestine.

Government-directed censorship on social media has grown in recent years in both the United States and Europe. And in the U.S., the Trump administration is seeking to deport a legal resident simply for leading anti-genocide protests on the campus of Columbia University.

Here in McBride’s Australia, a judge is deciding the case of a presenter who sued the ABC public broadcaster claiming she was sacked for sharing a Human Rights Watch tweet saying Israel was using starvation as a weapon of war.

The Australian Zionist Federation is also considering whether to bring formal charges against journalist Mary Kostakidis, whom it brought before the Australian Human Rights Commission for alleged anti-semitism for a series of her tweets.

A McBride victory on appeal would be a stunning breakthrough against this disturbing trend. [See: A Time of Growing Repression]

Background to the Case

In 2014, McBride made internal allegations after learning of murders of Afghan civilians by Australian soldiers. He then began leaking evidence of the cover-up of the crimes by senior officers to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the national broadcaster, between 2014 and 2016.

Australian Major General Justice Paul Brereton began an investigation in May 2016 into the allegations.

The ABC then broadcast a report in 2017 about the murder of innocent Afghans based on evidence supplied by McBride and a second whistleblower.

In September 2018 McBride was arrested and charged with allegedly stealing government property in violation of the Criminal Code Act 1995. In March 2019 he was charged with three more alleged crimes in breach of the Defence Act 1903 as well as “unlawfully disclosing a government document” contrary, allegedly, to the Crimes Act 1914.

On June 5, 2019 the Australian Federal Police raided the ABC’s Sydney headquarters for eight hours and removed files. The attorney general ultimately decided against prosecuting an ABC journalist, Dan Oakes, who had worked on the Afghan Files story.

Brereton made his findings public in November 2020, pointing to “credible information” about Australian war crimes. The report accused Australian special forces of murdering 39 unarmed Afghans but it did not implicate senior officers.

Three years later, in March 2023, the first soldier was charged with murder but it hasn’t yet led to a conviction.

The Trial

Davd McBride with his legal team and dog Jake arrive at the Supreme Court for his trial in November 2023, where h would plead guilty on all counts. (Joe Lauria)

McBride went on trial in November 2023. The prosecution argued that McBride broke laws of military discipline by leaking to the Australian media. McBride’s lawyers conceded in court that he indeed broke such regulations but that he had a paramount duty to the nation that superseded military discipline.

At the heart of the preliminary argument was the question: whom does a soldier serve?

Trish McDonald, the chief prosecutor, said the concept of duty in the law is that it is not in the public interest to reveal classified information to the public.

McBride’s primary duty, she said, was to follow orders. The accused was a legal officer, she asserted. He was not appointed to inform the press. He contravened his official duty. In fact, there is a public interest in non-disclosure, the prosecutor argued.

At trial, another King’s counsellor, Andrew Berger, implied that covering up alleged war crimes might be in the interests of Australia’s ties to the U.S. Under the U.S. Leahy Law, the Pentagon and State Dept. are barred from funding foreign military units that violate human rights with impunity.

Berger told the court: “It is a nuanced field: the very important relationship with Australia’s foreign partners. The public interest in maintaining confidentiality outweighs the interest of open justice.”

Two Ships in the Night

The defense agreed that while McBride had broken military regulations, he had a duty to the nation to do so.

Stephen Odgers, the chief defence counsel, gave an example of two ships on a collision course with the captain under strict military orders not to reveal the location of his ship. The captain had to disobey the order to avoid a collision. It would be a breach of a lawful order, he said, which would be a matter for a military tribunal, not a civilian court.

Odgers also argued that an Australian soldier’s duty is based on oath to serve the British sovereign, whose duty is to care for the interests of the entire nation.

“The defense arguments go nowhere,” McDonald told the court. The first thing to notice about a soldier’s oath is the wording, she said, and the word is “serve.”

In the context of McBride, it meant “giving service to the Queen,” she said. “’Serve’ here does not mean act in the public interest. It means nothing more nor less than render service,” said McDonald.

She went on: “’Serve’ means to a commander, to fight for or to obey in military actions, not in the context of interpreting an oath.”

“To interpret ‘serve’ to mean to act in the public interest, is to turn on its head service to king or queen,” she said. It is not “for the soldier to do whatever he thinks is right.” But is a soldier to fight and die to defend the nation or only the monarch?

“Nowhere in the oath does it refer to public interest or that” a soldier “must act in the public interest,” she added. If it were, Parliament would have said so, she said.

McDonald quoted an 19th century reference on military justice and statutory powers, saying, “There is nothing so dangerous to the civil establishment of the state as an undisciplined or reactionary army.”

McBride’s chief trial attorney Odgers, countered that, “The duty to serve the sovereign does not require blind obedience to orders.” He asked that the judge instruct the jury on the law that would allow it to decide on this.

Odgers said in the “21st Century for the Crown to make the assertion that to obey unquestionably, the orders of superiors ignores Nuremberg and the acceptance in our society that members of the military have higher duties.”

The Nuremberg Tribunal that tried Nazi war criminals established that a soldier had a duty to disobey unlawful orders.

The Plea

McBride leaving Supreme Court during break in his trial in November 2023. (Cathy Vogan/Consortium News)

David Mossop, the trial judge, ruled on Nov. 17, 2023 that he would instruct the jury, which was to be selected the following Monday, to disregard any public interest in the defense. “There is no aspect of duty that allows the accused to act in the public interest contrary to a lawful order,” he told the court.

McBride’s legal team tried to appeal that decision, but its application was denied by Supreme Court Chief Justice Lucy McCallum the same morning. In the afternoon Mossop ordered that agents of the Attorney General’s office could remove classified documents from the defense’s possession, which McBride’s team had intended to present, in a highly redacted form, to the jury.

Because of those regressive rulings, McBride accepted his attorneys’ advice that, left with no viable defense, he should plead guilty. On being arraigned for a second time, a defiant McBride stood in courtroom SC7 before a microphone placed in front of him and pronounced “Guilty” to each count read out to him.

On the street outside the courthouse immediately afterward, McBride’s trial lawyer, Mark Davis told reporters: “We received the decision just this afternoon, which was in essence to remove evidence from the defense. … The Crown, the government, was given the authority to bundle up evidence and run out the backdoor with it. He is no longer able to put it before a jury.”

Davis said:

“It was the fatal blow made in conjunction with the decision a few days ago that limits what we can say to the jury on David’s behalf in terms of what his duty as an officer was on the oath he took to serve, as we say, the interests of the Australian people.

Well the ruling was: he doesn’t have a duty to serve the interests of the Australian people. He has a duty to follow orders. That is a very narrow understanding of the law in our view that takes us back really to pre-World War II. We all know how military law has been judged since then in terms of compliance to follow orders.

So facing that reality, we’re limited in terms of what we could put to a jury in term’s of David’s duty … together with the removal of evidence makes it impossible, realistically, to go to trial. It is a sad day and a difficult day for us to advise David on his options this afternoon and he embraced them.”

McBride said: “I stand tall and I believe I did my duty and I don’t see it as a defeat. I see it as a beginning of a better Australia.”

The Sentencing

McBride was sentenced to a draconian 5 years and 8 months in prison by Mossop on May 13, 2024. Mossop told the court at sentencing that McBride thought he knew better than the Australian Defence Force. “It is imperative that others be generally deterred from holding such attitudes,” he said.

Whether McBride’s actions had caused harm was central to his sentence. His lawyers argued until the end on Tuesday that there was no evidence of harm and that the risk was minimal because he had given the material to professional journalists.

But Mossop ruled Tuesday that the “nature of the offending, harm,” and a “lack of contrition all give rise to the need to give general deterrence – to prevent any further disclosures of this kind.”

The judge quoted McBride as saying: “I never said I would coverup crimes for the government.” Mossop told the court that McBride accessed documents and stored them in a personal folder. “He then removed this information – some 237 docs, 209 of which were classified ‘Secret” – and took them home,” the judge said.

The Australian Federal Police “seized the documents from his home, giving rise to the charge of theft.”

The judge said McBride’s lawyers argued his motivation was neither financial gain, nor to aid Australia’s enemies. that he believed he was not committing an offence.

Mossop said McBride admitted to taking the documents but in pursuit of a legal aim – within the Protective Disclosure Act, that McBride claimed he had a legal obligation to disclose. “He showed no remorse,” the judge said.

Davis said McBride would appeal. He called it an “extremely heavy sentence” particularly since the government “conceded” McBride “caused no harm” and it did not personally benefit him.

In the street outside the courthouse, Davis said:

“It’s an issue of international importance that a Western nation has such a narrow definition of duty. We say David McBride fulfilled his duty and he wished to put it to a jury that he conducted himself according to the oath he gave to his nation.”

A Report Delayed

An independent report into the Afghan war crimes, which could have had a bearing on the outcome of McBride’s case, was not released by the Australian Defence Minister Richard Marles until the day of sentencing. The Afghanistan Inquiry Implementation Oversight Panel Report was completed on Nov. 8, 2023 — nine days before Mossop rejected a public interest defense leading to McBride’s guilty plea.

The independent panel report was withheld by Marles until the day of McBride’s sentencing because, as Marles wrote in the cover letter, “disclosure of the documents by these orders would, or could reasonably be expected to, prejudice legal proceedings – specifically current and future war crimes prosecutions.”

The independent report reversed the findings of the 2020 Bereton Report. It said:

“The Panel did not agree with the Brereton Inquiry’s view that some accountability and responsibility could not fall on the most senior officers and it suggested that issue should be the subject of further consideration. […]

There is ongoing anger and bitter resentment amongst present and former members of the special forces, many of whom served with distinction in Afghanistan, that their senior officers have not publicly accepted some responsibility for policies or decisions that contributed to the misconduct, such as the overuse of special forces.”

It said:

“Throughout his Report, Major General Brereton attributed or dismissed legal, moral and collective accountability for the incidents that were uncovered, factors which contributed to their occurrence, actions or behaviours which facilitated them and governance oversights and failures. […] the terms of reference for the Inquiry and its reporting obligations, was such that the highest levels of Defence leadership at the relevant times were not required to give evidence to the Inquiry and were not included in the Inquiry’s attribution of accountability.”

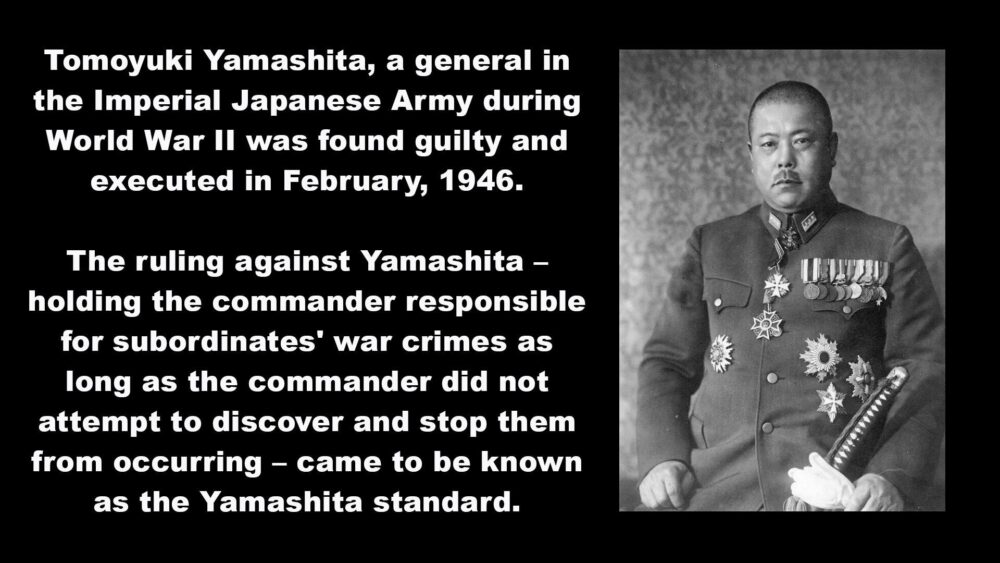

The report would have provided evidence to support McBride’s contention that senior officers were not held to account for their part in the war crimes, even if there was no direct evidence of their participation in them. McBride had taught other military lawyers about the so-called Yamashita Standard.

Tomoyuki Yamashita was a World War II Japanese general who was found guilty by an American military tribunal in Manila and executed in February 1946. He was held to be responsible for subordinates’ war crimes as long as he did not attempt to discover and stop the crimes from happening.

“If they didn’t know, they should know,” said federal Senator David Shoebridge outside the Supreme Court building in Canberra before McBride’s appeal hearing this month. “I can tell you now there were multiple reports going up the chain about the war crimes in Afghanistan. How is it that nobody in a position of senior leadership in the ADF has ever been seriously challenged? Something is wrong.”

Shoebridge said the independent panel’s report was “buried, literally buried by the Albanese government.” He said, “We have a system in which power protects power in this country. And David tried to … knock a hole in this wall of protection for senior decision makers. And if you want to know why he’s in jail, it’s because of that. … He said surely there is a higher good, surely there is a public interest which should break that wall down of impunity.”

Shoebridge said McBride was denied presenting evidence because the court said it would prejudice national security. “I can tell you now what prejudices national security: a sense of impunity in the senior leadership … breaking international laws and destroying Australia’s international reputation … that’s what impacts national security,” he said.

Not only ought the brass have known about atrocities in 2012; they should have backed their legal officer in bringing prosecutions, McBride’s lawyers argue. Instead they turned against McBride, covered up the atrocities and investigated other soldiers, who from 2013, had not committed serious crimes, or no crime at all.

“I actually say the problem is with the generals, not with the corporals and privates,” McBride said at a rally on the eve of his 2023 trial. “You people know that it it’s not going to make this country better if we put a private soldier in jail.”

The independent panel report also raised the alarm about the ADF’s “systematic” move away from a just war theory based on natural law, which seeks to minimize civilian casualties, to the ADF’s use of utilitarian ethics that justifies unrestrained violence or torture if it is a means to a desired outcome.

Because the independent report was released after McBride’s conviction and sentencing it is considered new evidence and not admissible to the appeals court.

The Appeal

At the appeal hearing on March 3, McBride’s attorney, Bill Neild, argued before Justices Belinda Baker, Louise Taylor and Wendy Abraham, that there had been a miscarriage of justice. He told the court McBride’s “pleas of guilty arose only because of the decisions made by his Honour Mossop J in relation to … questions of law and not because the appellant had any genuine belief that he was guilty of the offences as charged.”

A miscarriage of justice prompted McBride to plead guilty only because of Mossop’s wrong decision that he would instruct the jury regarding the definition of duty, Neild contended. And for Mossop, that definition of “duty was in a sufficiently similar way to the way in which a master is entitled to order his servant.”

Neild sought to distinguish between “duty” and “official duty.” Though the government says the duty to obey orders is central to military discipline, it doesn’t follow that this discipline is the same as “official duty,” which c0mes with taking an oath of office, McBride’s barrister argued.

Duty under his oath to the British monarch was to serve the King, who serves the interest of the public, Neild argued. McBride believed he was lawfully upholding his oath as a legal officer whose “paramount” duty is to administer justice in the public interest.

McBride “believed he was acting in accordance with that duty by courageously standing up for what he believed was right and speaking out robustly and openly against what he believed was wrong in the Australian Defence Force,” Neild said.

“At trial, it would be a question for the jury whether in so acting” he had served the public, and it would be up to the government to “prove beyond reasonable doubt that his conduct was not reasonably necessary to advance the Australian public interest,” Neild argued. Mossop mistakenly said he would instruct the jury to disregard any defense in the public interest at all, however.

This argument could lead the three judges in this case to determine whom the British monarch ultimately serves. [They should also be considering whether it is a soldier’s duty to only fight for and defend the King, or to defend the nation? In the U.S., at least on paper, a soldier’s oath is to defend the Constitution, not the president.]

McBride wants Mossop’s ruling to be overturned and a trial to be held before a jury, which would be allowed to hear such a defense. Alternately, McBride is appealing for a reduction of sentence to community service.

[See: Thread of Consortium News‘ Live Tweeting of Appeal Hearing.]

The Government’s Response

McDonald for the government flatly argued that

“There is nothing in the oath of allegiance [to the Crown] which mentions the public interest. … The content of the oath of enlistment is set out. As we submitted, there is no mention of anything to do with the public interest. What we would draw your Honours’ attention to are … two parts of [the oath]. First, that it requires that the particular member of the Defence Forces ‘will well and truly serve the sovereign’. So there is a concept of service.

And then finally, within the oath, ‘will faithfully discharge my duty according to law’. And, in our submissions, not only does that oath not refer to public interest, but, indeed, when one looks at its actual terms, it is the antithesis of a concept that a member of the Defence Forces would have … discretion not to obey an order or to act in some way contrary to the Defence Forces because that member of the Defence Forces perceived that it was in the public interest.”

The question, or the concept of service … is in line with the inherent nature of a military service. And … it’s an inherent part of the military that orders are issued, orders are made by superiors, and they are followed by inferior officers. …

The oath requires ‘to discharge my duty according to law’, and again, the concept of ‘according to law’ incorporates matters such as general orders that are made by the military requiring members of the Defence Forces to comply with those orders.”

The three judges should be grappling with a collision between monarchy and democracy: does the monarch serve his people or does he ultimately serve no one except the interests of the elite to cover up war crimes? And to whom then does a soldier’s loyalty lie? Is a soldier’s life to be sacrificed to defend the nation or just the King?

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former U.N. correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and other newspapers, including The Montreal Gazette, the London Daily Mail and The Star of Johannesburg. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London, a financial reporter for Bloomberg News and began his professional work as a 19-year old stringer for The New York Times. He is the author of two books, A Political Odyssey, with Sen. Mike Gravel, foreword by Daniel Ellsberg; and How I Lost By Hillary Clinton, foreword by Julian Assange.

Very intriguing legal argument over the concepts of duty and obey. What is duty? and who obeys whom? Do you obey God? how about traffic signals? your employer? and what duties do you have to family? job? to protect the environment ? and duties on and on throughout human experience. We could have a new noun “obeduty” which could become useful for psychiatry.

The Medieval political demand of fealty to the Lord is a master/slave relationship. In McBride’s case, that it collides with modern democratic individualism is a good plot.

The excuse of the criminals of the Third Reich when tried at Nuremberg was always “I was just following orders.” They were hanged anyway. Does the western world now think that the Nazis should have been excused? If not, then neither should David McBride, or Julian Assange, or any other whistleblower anywhere in the world. Those who declare loyalty to a king are slaves.

Blessing to the whistleblowers, they represent the true guardians of justice.

In America at least, it has been decided that the People are above the Government. The very first words of the Constitution (if you can find a copy in a DC bathroom) begin with “We the People in order to form …”. In America, it has been settled since the 18th Century that its People are more important than Government. Loyalty to the American people is likewise more important than loyalty to the government. Anyone who says otherwise is Anti-American! (note I am not a lawyer – do not take this as legal advice!)

In fact, in any country claiming to be a democracy, it has to be People first. The definition of a democracy is that the power lies in the hands of the people, and that it is the people who form a government and give that government a bit of their power so they can run a good fire department and build good flood control.

But if it says Democracy on the label, then its supposed to be the People who have the Power.

Cue Patty Smith …. I do miss punk, so much more fun that Beyonce or that Taylor girl. Now I’ve got an urge to hear “Gloria.” Gotta Go.

this > , the sentence , the quote , 2 queries:

The nuance ?

————

“McBride went on trial in November 2023. The prosecution argued that McBride broke laws of military discipline by leaking to the Australian media. McBride’s lawyers conceded in court that he indeed broke such regulations but that he had a paramount duty to the nation that superseded military discipline.”

————

#1 – query “what defines discipline vs law” – AI result:

AI Overview

Learn more

While both discipline and law involve rules and consequences, discipline focuses on internal self-control and guidance, while law is a formal system of rules enforced by a governing authority.

Here’s a more detailed breakdown:

Discipline:

Definition:

Discipline refers to training that corrects, improves, or controls someone’s behavior or actions. It can be internal (self-discipline) or external (discipline imposed by others).

Examples:

A parent teaching a child to clean up their toys.

A coach teaching a team to follow a strategy.

An individual practicing self-control to achieve a goal.

Focus:

Discipline aims to foster good habits, self-control, and adherence to rules and standards.

Enforcement:

Discipline can be enforced through guidance, instruction, and consequences, but it often lacks the formal authority of law.

Law:

Definition:

Law is a system of rules and regulations established by a governing authority to maintain order and justice.

Examples:

Traffic laws that regulate driving.

Criminal laws that define crimes and punishments.

Contract laws that govern agreements between parties.

Focus:

Law aims to establish a framework for societal behavior, protect individuals and property, and resolve disputes.

Enforcement:

Law is enforced by formal institutions, such as courts, police, and other law enforcement agencies.

—————

#2 – query “regulation vs law” – AI result – briefly:

Laws are written and enacted by legislative bodies like Congress, while regulations are detailed rules and standards created by government agencies to implement and enforce those laws.

Statutes also referred to as codes, are laws written and enacted by the legislative branch of government (e.g, U.S. Congress, state legislators). Regulations also referred to as rules, are written by agencies (e.g., Environmental Protection Agency) to supplement laws that were passed by the legislature