Global South writers and policymakers have imagined and created futures beyond colonialism and environmental destruction.

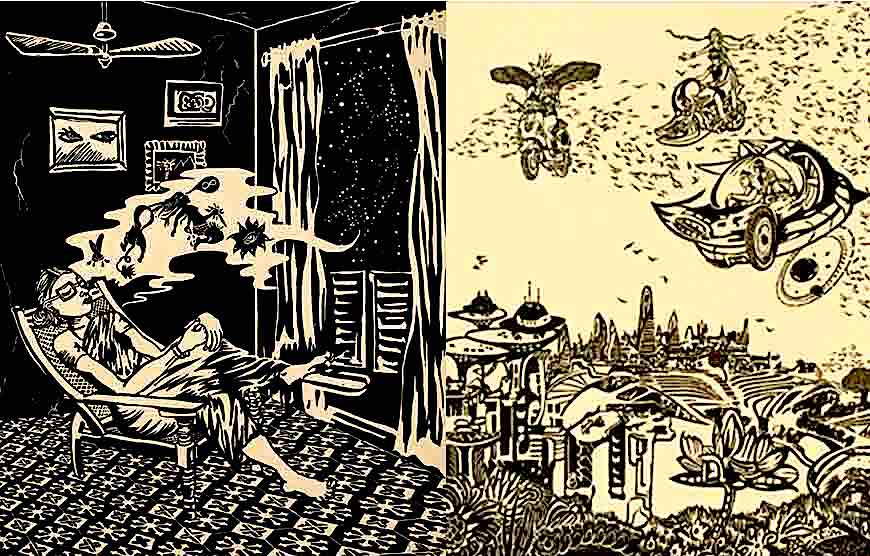

Chitra Ganesh, United States, Sultana’s Dream, 2018, a series of 27 linocuts published by Durham Press, © Chitra Ganesh. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

Lost in a colonial fog of inferiority, writers across Asia imagined a world that was beyond the reach of colonialism’s devastation.

Lost in a colonial fog of inferiority, writers across Asia imagined a world that was beyond the reach of colonialism’s devastation.

In 1835, Kylas Chunder Dutt (1817–1859) wrote a remarkable story called “A Journal of Forty-Eight Hours of the Year 1945.” The story, published in The Calcutta Literary Gazette, came out when the great French science fiction novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905) was only 7 years old. Dutt’s account is not strictly science fiction, but largely futuristic.

The 18-year-old opened his story with this line:

“The people of India and particularly those of the metropolis had been subject for the last fifty years to every species of subaltern oppression. … With the rapidity of lightning the spirit of Rebellion spread through this once pacific people.”

They were ready for rebellion. The story imagines a two-day period [110 years in the future] in 1945 when a 25 year-old man named Bhoobun Mohun leads an uprising against British rule but is subsequently defeated and executed.

Several important books appeared in Bengal over the decades that imagined a world beyond the colonial one.

Dutt’s cousin, Shoshee Chunder Dutt, published The Republic of Orissa: Annals from the Pages of the Twentieth Century in 1845; Hemlal Dutta published Rahasya (The Mystery) in 1882; Pandit Ambika Dutt Vyas published Ascharya Vrittant (The Strange Tale) in 1884–1888; Jagdish Chandra Bose published Niruddesher Kahini (The Story of the Missing One) in 1896; and Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain published Sultana’s Dream in 1905.

Begum Rokeya’s story is the most authentically science fiction, since she imagines a world in which technology (flying cars, solar power, robotic farming) can liberate humans from patriarchy.

As in India, Chinese writers who felt the onus of the late Qing monarchy and the semi-colonial occupation of their country began to imagine rebellion and freedom.

In 1902, Liang Qichao published his translation into Chinese of Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1869–1870) and his own story, Xin Zhongguo weilaiji (The Future of New China).

The experience of reading Verne’s forecasting of how science would help liberate humankind provided a tonic for Liang Qichao and for Lu Xun, one of the most influential writers of his generation, who also translated one of Verne’s novels, From the Earth to the Moon (1865), and published it in 1903.

Liang Qichao’s story imagined the World Expo in Shanghai in the 1960s, when China was going to be one of the most important countries in the world. Just as Begum Rokeya imagined solar power as the energy for a free Bengal, Chinese science fiction writers of the late Qing period imagined underwater travel, wind-powered railways and hydrogen balloons as the means to liberate China.

Science, in this anti-colonial imagination, was one of the tools for building a utopia.

When reading through the essays from the latest issue of Wenhua Zongheng: A Journal of Contemporary Chinese Thought, I was reminded often of this great seam of science fiction writing. The issue is dedicated to China’s ecological transition.

Even though there are reports from the field about major changes that have been afoot in China for a generation, what the three essays in the journal describe is nothing short of science fiction.

Shang Yang, China, Remaining Water-1, mixed media, 2015. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

Just a little more than a decade ago, the air quality in Beijing, for instance, was abysmal. Some days, the soot would gather on your face and leave a film of unidentifiable chemical matter.

Distress at this situation led to the announcement on June 14, 2013, by the State Council of the 2013–2017 Air Pollution Prevention and Control Action Plan, which contained 10 policy measures backed by almost RMB 1.7 trillion. Within a decade, the air quality in the capital improved dramatically, largely due to the focused effort to lessen the use of carbon fuels.

Then Vice Minister of Environmental Protection Pan Yue participated in an important study in 2004 that offered a calculation for “Green GDP,” or a better way to account for growth without environmental damage.

The 18th Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012 proposed a new framework for development called “ecological civilisation.” Already in 2005, Xi Jinping, then secretary of the Zhejiang Provincial Party Committee, put forward a vision that has become widely promoted: “clean waters and green mountains are as valuable as gold and silver mountains.”

The report by Xiong Jie and Tings Chak, both from Wenhua Zongheng’s editorial team and Tricontinental, shows how the Erhai Lake in Yunnan Province went from one of the most polluted in China to one of the cleanest.

Four factors are key to this clean-up: the determination of the people who lived on the lake to save it; the discipline of the local government authorities to balance the short-term needs of the people with the long-term needs of the environment; the expertise of the scientific community in the region that brought to bear studies of the lake, the causes of the pollution, and a fact-based plan to clean up its waters; and the commitment of the Communist Party of China cadre to work hard to implement the government’s scientific policy.

What made this report so interesting for me is that nothing in it is outside the realm of possibility for any polluted lake in any Global South country.

Pan Yuliang, China, Penguins, 1942. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

The essay by professors Ding Ling (Anhui Normal University) and Xu Zhun (City University of New York), as well as the introductory essay by João Pedro Stédile (Brazil’s Landless Workers Movement, MST), reflect on the need for ecological agriculture that takes into account both the importance of improving yields and environmental protection.

But how is this possible? In the Wanzhi District, for instance, due to the high price of crayfish, it would be more profitable for the farmers of the Dongba Village Cooperative to cultivate them directly in ponds.

But the cooperative made a political decision to adopt a composite farming model that integrates rice cultivation with crayfish farming for two reasons. First, it was important for the cooperative to grow rice, a staple of the area, and therefore ensure their food sovereignty.

Second, they returned the rice straw to the fields as rich feed for the next season’s crayfish, thereby increasing yields. Scientists come in on a regular basis to cultivate beneficial algae and bacteria to improve the water quality.

A test of their success was that egrets, which were rarely seen in the area, have returned to the fields.

In the third article, Professor Feng Kaidong (Peking University) and Chen Junting (Peking University) provide a very good overview of China’s new energy vehicle industry, focusing, of course, on electric cars.

Tesla is a well-known global brand, but it is being challenged around the world for market share by a series of Chinese-made electric vehicles by brands such as Omoda and MG (both state-owned), BYD, and Ora. These already outsell the Western brands in Asia and are largely produced with Chinese technology.

Oslo, Norway, has the highest percentage of electric cars per capita, but the two main Chinese cities of Beijing and Shanghai have the largest absolute number of electric cars. Their streets are eerily quiet, with electric cars and motorcycles humming silently by.

Two of the reasons why China has been able to break the Gordian knot of the internal combustion engine are that the country’s government is not strangled by the petrochemical lobby, and the country’s technological sectors (in transportation and information technology, for instance) are able to collaborate and not see themselves as separate profit-making enterprises.

Huang Yuxing, China, Land of Growth, 2015–2016. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

In 2019, Chen Qiufan published Waste Tide, a remarkable dystopian science fiction novel about Silicon Isle, a place that is saturated with electronic waste that has produced all manner of biochemical distortions in humans and animals.

The “waste people” of Silicon Isle live surrounded by jelly fish that emit “blue green LED lights.” To survive, they sift through toxic waters, their skin peeling off from prolonged exposure. At one point, the protagonist, Mimi, encounters a dead dog that wags its tail as she approaches, its body reanimated by the chemicals and detritus of discarded technology.

Chen’s novel is a fabulous depiction of the horrors of environmental destruction. It reads less like science fiction and more like a report from the field, a documentary of the town of Guiyu in Guangdong Province, which had been the centre of e-waste disposal, or a fantastical depiction of life on the Great Pacific Plastic Patch (20 million square kilometres of plastic trash caught in a vortex in the northern Pacific Ocean).

Chen has said that his novel was loosely based on the reality of Guiyu, whose soil and air had been contaminated by the metals and chemicals of digital society.

In 2013, Guiyu’s local government began to construct an industrial park to house recycling units and better regulate their environmental practices. When the park was ready two years later most of the small recycling factories shut down, while the larger ones moved into the park.

Then, in 2018, the Chinese government banned the import of 24 varieties of waste, including electronic, plastic and textile waste (most of it coming from the Global North). This has meant that Guiyu will only have to deal with the historical residue of environmental damage rather than with enormous new volumes of waste.

The actual history of Guiyu is writing a new ending for Chen Qiufan’s fictitious Waste Tide.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director ofTricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow atChongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and, with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

We do write similar stories here in the West as well, though I will grant that it does not much show in our politics.

There are lots of viable solutions that could be implemented, though of course that part is not fiction.

The global South may well implement practical solutions before these become dominant in the US or Europe, though. Despite some admirable efforts, the greenwashing and the routine institutional backlash are difficult to work around at anything over the smallest scale.

Yes, we write against colonialism, empire and abuses of power but most venues don’t accept such nitty-gritty social realism. One place that does is the Blue Collar Review.

Absorbing. Thank you, Vijay.