From Los Angeles’ fires to Asheville’s floods, disasters are intensifying and demand resilience that megabanks can’t provide, writes Trinity Tran.

A Chase Bank branch on Sunset Boulevard burning on Jan. 8. (CAL FIRE_Official – Palisades Fire, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

By Trinity Tran

Common Dreams

On the night of Jan. 7, as the Palisades Fire surged to 2,000 acres to the west and the Eaton Fire exploded to 1,000 to the east, I joined thousands fleeing hurricane-force winds that hurled embers for miles. I evacuated out of precaution, but across Los Angeles, many Angelenos were not as fortunate.

On the night of Jan. 7, as the Palisades Fire surged to 2,000 acres to the west and the Eaton Fire exploded to 1,000 to the east, I joined thousands fleeing hurricane-force winds that hurled embers for miles. I evacuated out of precaution, but across Los Angeles, many Angelenos were not as fortunate.

Like so many here, I spent those first sleepless nights glued to wall-to-wall news coverage, tracking the fires’ paths. But while flames dominated headlines, a slower crisis burns, one that Los Angeles has yet to confront.

Caught in a cycle of destruction and recovery that grows more urgent every year, fire season is no longer a season — it’s a year-round threat.

Entire neighborhoods in Altadena have lost more than residences — they’ve watched their generational wealth turn to rubble. In Pacific Palisades, emergency teams scrambled to stabilize hillsides before landslides erased what remained.

With wildfire losses now climbing past $250 billion, one question echoes through the city: Who pays to rebuild? And how can we do it faster, smarter, without sinking deeper into debt?

Los Angeles isn’t the first to face this reckoning. Back in 1997, Grand Forks, North Dakota, suffered a catastrophic flood. Their city was left in ruins, but they had something most cities don’t: the Bank of North Dakota (BND), America’s only state-owned public bank.

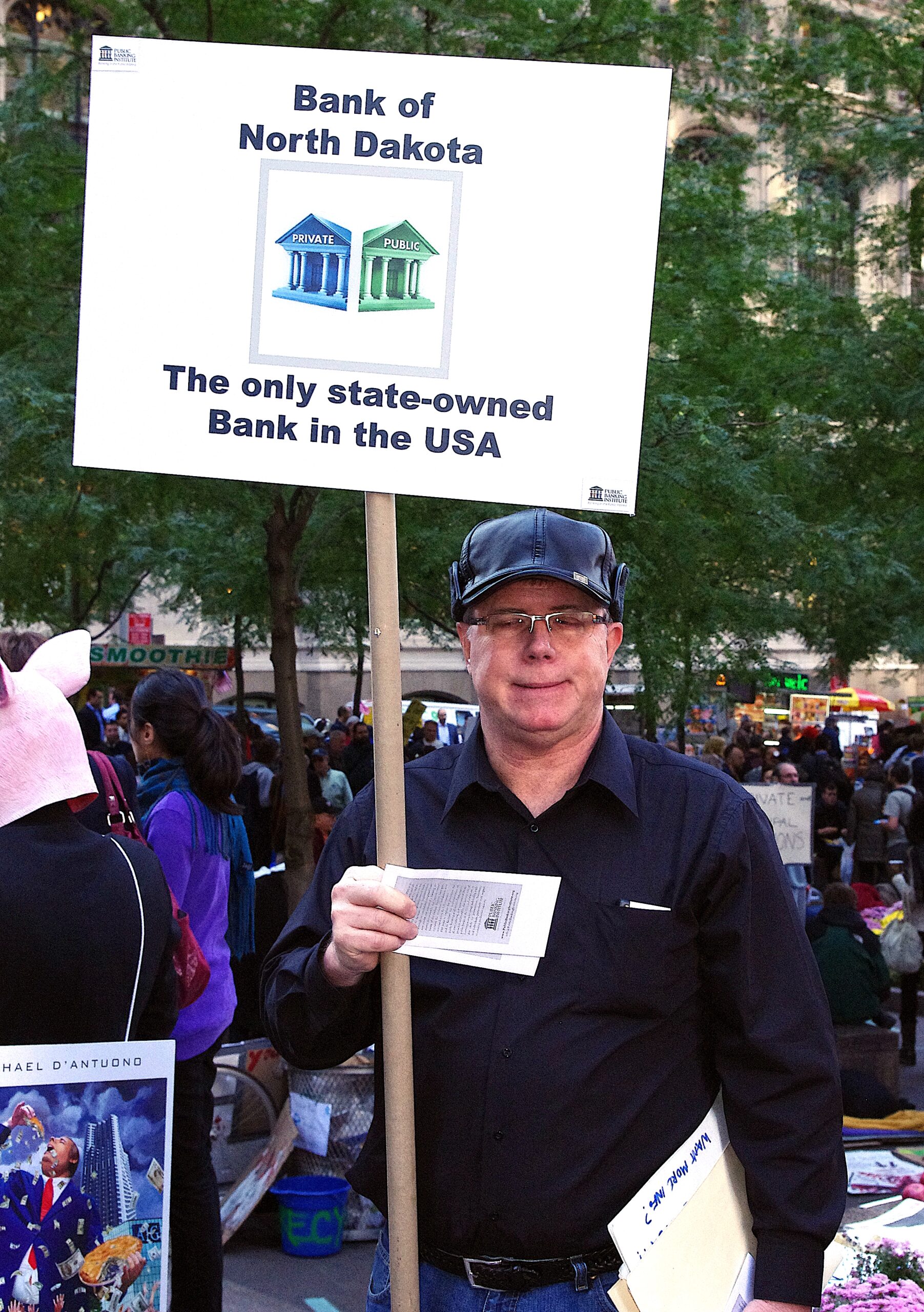

Advertising the Bank of North Dakota at Occupy Wall Street in October 2011. (David Shankbone, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

Within two weeks, the BND funneled around $70 million in credit for emergency operations and rebuilding. While FEMA took months to distribute aid, the BND’s local presence and public mandate allowed it to act with precision. ND mortgage holders got six-month payment pauses. Show me one Wall Street bank that’s offered that kind of breathing room.

This is the power of public banking: swift, people-focused and designed for crisis response.

Unlike profit-driven institutions, a public bank — owned by a city or state — would reinvest public deposits into local resilience rather than shareholder dividends. Imagine transforming tax dollars into a renewable resource: funding fire-resistant infrastructure, upgrading aging power grids, and keeping families housed during disasters.

Look around Los Angeles today. Insurers flee high-risk areas, leaving families stranded. Meanwhile, we’re sending more than $1.4 billion a year in debt service fees to Wall Street — this staggering sum, outlined in the City’s 2024/25 Adopted Budget (Page R-71), is money that could fortify hillsides or retrofit homes.

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s $2.5 billion wildfire package helps clear debris, but it doesn’t address the bigger question: How do we fund tomorrow’s disasters without predatory loans that bleed the city dry?

U.S. President Joe Biden with Gov. Newsom monitoring the Los Angeles fires on Jan. 8. (The Biden White House, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

A public bank is the answer. Picture the Bank of North Dakota model scaled for a metropolis. Need emergency credit after the next natural disaster? Done. Low-interest loans for small businesses distributing supplies mid-crisis? No delays. By partnering with local lenders, a public bank could bridge the gap for families waiting months or years for insurance payouts.

This is the power of public banking: swift, people-focused, and designed for crisis response.

This isn’t fantasy. A national public banking movement is rising. In 2019, California passed the Public Banking Act, clearing the legal path for cities like Los Angeles to establish their own public banks.

A neighborhood in Los Angeles on Jan. 14 that was devastated by the Palisades Fire. (U.S. Army, Jon Soucy, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

New York City plans a public bank to fund affordable housing and support minority communities.

Florida eyes the model for local control of state resources.

From San Francisco to New Jersey, cities and states recognize that megabanks can’t meet the scale of today’s economic and environmental challenges. Public institutions keep dollars local, funding fire-resilient housing, green energy projects, and businesses that anchor communities during crises.

During Covid-19, the Bank of North Dakota proved this again. While Wall Street prioritized corporations, the BND partnered with community banks to quickly deliver relief to small businesses and frontline workers.

Los Angeles deserves that same agility. A public bank could centralize disaster funds, slash bureaucratic delays, and ensure every dollar stays local — rebuilding neighborhoods instead of enriching distant shareholders.

Housing offers another critical test. Today, financing affordable projects takes years as developers navigate a maze of private lenders.

A public bank could create a housing fast-track fund, offering below-market loans for shovel-ready developments. Interest payments would recycle into future projects, not Wall Street bonuses. Streamlined funding means lower costs, faster construction, and more Angelenos housed before the next disaster strikes.

Critics argue public banks risk politicization. But the BND’s 105-year track record in a solidly red state disproves this: it’s rated A+ by S&P with an 18.2 percent return on equity in 2023. It’s safer than most big banks and exceptionally stable as a public institution.

By law, California’s public banks won’t compete with local community banks, instead, they will partner with them, expanding access to credit in underserved communities.

The money to capitalize a public bank exists. We’ve already raised billions for disaster recovery. The fight isn’t about resources — it’s about control. A public bank keeps investments local, ensuring funds flow to priorities like firebreaks and microgrids rather than stock buybacks.

From LA’s wildfires to Asheville’s floods, disasters are intensifying and demand resilience. Public banking offers a blueprint for recovery: leverage public dollars to cut long-term costs, create jobs and rebuild smarter.

Los Angeles can lead this revolution. By creating the nation’s first major urban public bank, we’ll pioneer a model for cities nationwide. When the next disaster strikes, we won’t be at the mercy of for-profit banks, we’ll have the tools to rebuild ourselves — faster, fairer, and permanently stronger. The alternative is unthinkable: another decade of rubble, debt and avoidable loss.

Trinity Tran co-founded the California Public Banking Alliance and Public Bank LA, spearheading the nation’s first laws to create public banks and universal banking services — transforming finance to reclaim public funds for communities, not corporations.

This article is from Common Dreams.

Views expressed in this article and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

So what about credit unions?? Pros/cons vs ‘public banks’? Or are they the same?

I wonder if you’ve ever watched “the Bank of Dave”? It’s about a local man in Burnley in the north west of England who was often lending people money and always got paid back. He decided to start a public bank called the Bank of Dave, his first name. The film details his struggles with the established banking system and politicians which he eventually won. The Bank of Dave is now a successful public bank.

Peering through the smoke, or looking over the receding flood waters, it can seem like the answer to our problems is to rebuild bigger and better, and to do that we just need easier access to more money, that makes the whole magic of more infrastructure possible. But we might want to let the smoke clear out of our eyes, and wash the muck from out from behind our eyelids so that we can see, that our problems will not be solved by building more planet consuming infrastructure. The answer to our problems is to rethink our way of life and instead of more, we need to focus on what is it we really need. As a former civil engineer, what I have learned is that what we really need is not more infrastructure, not more single-family oversized homes, not more roads, not more bridges, not more dams, not more levies, not more solar panels, not more windmills, but rather more imagination. What we need is to change our focus from the insanity produced by following the more, more, more mantra and begin to look for ways to reconnect with each other and the planet that provides for us exactly what we need, which we can only realize when we stop consuming the planet.

ADD to this: Public insurance as a PUBLIC UTILITY. Let the PRIVATE insurance companies flee to hell as far as I’m concerned as we wouldn’t need them if we here in California as well as other states do the same. And for that matter, let the Wall Street banks join the insurance companies in HELL where they all belong!

A great idea, but if public banking starts to take hold, big private banks will do everything in their power to destroy them. It’s worth the fight! We must remove parasitical private banks.

we need publicbanks publicly owned utilities massive cuts military spending with redirrction to public majority power. that means begining democracy and ending capitalism.

fs