The U.S. took advantage of a changing regional and domestic environment to make a favorable arrangement for itself this time. But the notion that it can drag Lebanon into the pro-Israeli orbit of the Gulf will prove illusory.

A U.S. Army Color Guard carries the Lebanese flag during a visit by Gen. Joseph K. Aoun, now the president of Lebanon, at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia on June 26, 2018. (U.S. Army, Elizabeth Fraser, Arlington National Cemetery)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

Finally, after two years and two months of a presidential vacuum, Lebanon has a new president.

Finally, after two years and two months of a presidential vacuum, Lebanon has a new president.

Western media coverage misses the essential point about the presidency of Lebanon: after the reforms of the Taif agreement in 1989, officially known as the National Reconciliation Accord, the Lebanese president lost his powers.

A look back at the history shows that the Lebanese president is now largely a token ruler who does not actually rule.

Before the Taif accords, which ended the 15-year Lebanese civil war, the Lebanese president was an absolutist who couldn’t be held accountable for his actions and ruled by decree.

The fact that Lebanon could survive without a president for more than two years is an indication of the president’s reduced role (and this is not the first time that Lebanon experienced such a presidential vacuum, it also happened after Emile Lahoud vacated the presidency at the end of his term in 2007).

The Lebanese Political System

Lebanon is more democratic than any other Arab country and freer than all countries of the Middle East. It is more democratic than Israel, an apartheid state that denies the vote to its occupied population.

But despite its freedoms, the Lebanese political system has been marred with sectarianism (the identification of citizens with the sect that they are born into, and the distribution of political power and posts according to an arithmetic formula which now divides seats equally between Muslims and Christians).

Since the French occupation of Lebanon after World War I, the seat of the presidency has been reserved for Maronite Christians, while the speaker is set aside for Shiite Muslims and the prime minister for Sunni Muslims.

Lebanon moved away from a presidential system to a quasi-parliamentary system after the 1989 Taif accords. This formal system does not fully explain power games behind the scenes because sectarian leaders — and even clerics, especially the Maronite patriarch — exercise tremendous political power and control over most of the political parties.

Prime Minister Has Most Power

Two important Maronite Christian symbols on Sassine Square in Beirut in November 2021: A statue of Saint Charbel, the most important Maronite saint; and a billboard on a side of a building showing Bachir Gemayel, the Maronite militia leader during the Civil War. (James Bradbury, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The political system since Taif gives the Sunni prime minister most of the authority but decisions are reached by the collective council of ministers, in which all sects are represented. The president can preside over the meetings of the council of ministers, but the latter can meet without him or her.

Moreover, the Lebanese political system is like the design of the American founding fathers who did not have much faith in the public, wanting an elite group to govern. It is for this reason that the U.S. Senate was established and its members given longer terms than in the House. It was only in 1913 that senators were popularly elected. Before that they were chosen by state legislators.

The House of Representatives was designed instead to represent “the people” (shop keepers, small traders, farmers and workers in the early days of the republic).

The unique, antiquated method by which Americans elect a president was designed to prevent “the people” (“we the people”?) from directly choosing a president. The electoral college was an elite club in which a privileged few could choose the national leader. The electors were first chosen by state legislators but are now based on the people’s vote in each state. However, the electors still choose the president regardless of the national popular vote.

In Lebanon, the people don’t get to vote for president at all. Instead, the Lebanese Parliament (which now has 128 members) gets to select the president. This has facilitated external intervention and made every presidential election a high season for bribery. Sometimes MPs get paid from more than one side.

Outside Interference

June 7, 2017: Gen Joseph Aoun, commander of the Lebanese Armed Forces, facing camera and now the country’s president, greeting Gen Joseph L. Votel, commander of U.S. Central Command, during Votel’s visit to Dahr Al Jabl overlook, near the Syrian border. (DoD, Dana Flamer)

This election was no different from previous ones insofar as outside powers exercised tremendous influence in the selection of the candidate and in the management of the vote in Parliament to choose him.

Foreign intervention in the affairs of Lebanon is as old as the life of the republic. In 1943, there were two major Maronite-led political groupings: the Constitutional Bloc and the Patriotic Bloc; the first was controlled by Britain and the second was controlled by France.

What is known in Lebanon as the struggle for independence in 1943 was merely a competition between the U.K. and France. The U.K. won and thus Lebanon gained its nominal independence.

The role of Britain and France receded after the Suez crisis in 1956, when the U.S. largely inherited the role of hegemon in the larger Middle East.

France continued to have a “special” role with the Maronite church and with Christians in Lebanon. In recent years, France has aligned itself with Sunni Muslims perhaps because of the dwindling numbers of Lebanese Christians.

U.S. Intervenes in Every Election

Lebanon’s President Camille Chamoun, left, with Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas in Brazil, 1954. (Arquivo Nacional, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

In every presidential (and parliamentary) election, the U.S. and others intervene directly. Ropes of Sand: America’s Failure in the Middle East by Wilbur Crane Eveland chronicles the era of Kamil Sham`un (president from 1952-1958).

It was the height of the Cold War and Sham`un violated the terms of the 1943 National Pact, which formalized independence from France and divvied up political power amongst the sects.

The Pact also required that Lebanon not join Western alliances in return for Muslims’ acceptance of the finality of Lebanon’s borders — a de facto rejection of the aspiration of larger, pan-Arab unity. Sham’un ignored the pact by actively joining the American alliance against not only communism, but also Arab socialism.

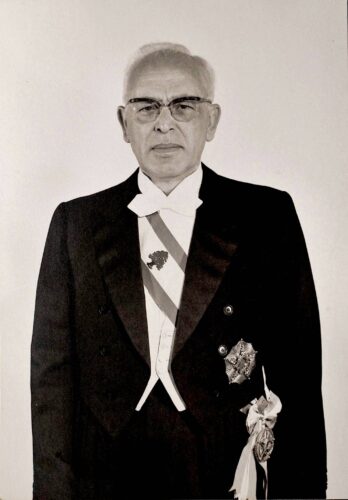

Fouad Chehab in 1961. (Keystone France, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The U.S. thus showered money and arms on his administration, which ignited a mini-civil war in 1958. In his book, Eveland describes how the C.I.A. used cash to buy seats in the Lebanese Parliament for Sham`un.

Nasser’s Role

After the civil war, it was not the Lebanese people nor the Lebanese MPs who chose the president. Instead, it was Gamal Abdel Nasser, the Egyptian leader, who came to an agreement with the U.S. administration to award the presidency to Gen. Fouad Shihab, who had succeeded in keeping the army neutral during the war.

Shihab served as president until 1964, when he was succeeded by a weak protégé, Charles Hilu. Hilu, however, quickly moved away from the policies of Shihab and aligned himself with right-wing Maronite political parties and with the West.

He even made Lebanon’s traditional alliance with the West stronger, thereby distancing himself from the foreign policy of Nasser.

A Foiled KGB Plot

In 1969, Lebanese Army intelligence (presumably benefiting from U.S. largesse to fight communism) foiled a KGB plot to smuggle a Mirage fighter jet out of Lebanon.

But Lebanese intelligence bungled the operation, shooting and wounding Soviet and Lebanese security officers and the event was publicized around the world. This embarrassed the Soviets, creating a rift with Lebanese intelligence, which was still under the sway of Shihab.

In the crucial 1970 presidential election (which was the closest ever in a Parliament of 99 members), Sulayman Franjiyyah (the candidate of the right-wing coalition and of the U.S. and Gulf regimes) won with one vote in his favor.

The candidate of the Shihabi movement lost and it was said that the U.S.S.R. convinced Kamal Jumblat, a socialist leader, to abandon the Shihabi candidate and vote instead for the Western candidate. (My father, who served as secretary-general of the Lebanese Parliament, was offered a suitcase full of cash if he were to change the vote of one MP in favor of the Western choice. He politely refused the offer from a Western intelligence source).

In 1976, at the end of Franjiyyah’s term, the Syrian and Saudi regimes supported the election of Ilyas Sarkis, who had lost to Franjiyyah in 1970.

Syria Installs Presidents (With US & KSA)

In 1982, it was Israel which installed two brothers as presidents in succession: first Bashir Gemayyel, who was assassinated just days after his installation, and then his brother, Amin.

When Amin’s term ended in 1988, the Syrian regime (often with Saudi and U.S. support) managed to select every president of Lebanon until the election of Michel Suleiman in 2008.

In the election five days ago, Joseph Awn (Aoun), the commander-in-chief of the Lebanese Army, was picked as president, and the price of the vote was said to have reached $200,000.

U.S. support was crucial and Barak Ravid of Axios exposed (among other media worldwide) the U.S. role in picking Awn. Syria and Iran lost their clout in Lebanon and Hizbullah is still suffering from devastating Israeli attacks.

The U.S. took advantage of a changing regional and domestic landscape and arranged the Lebanese political system in its, and Israel’s favor.

But the U.S. is typically short-sighted. Hizbullah and its partner, Amal, represent more than 95 percent of all Shiites, who remain the single largest sect in Lebanon. They suffer fewer losses to migration than other sects because the doors of the Gulf are closed to them.

The U.S. won’t be able to control Lebanon for long. Hizbullah is much weaker, but it remains a power to be reckoned with, especially domestically.

The notion that the U.S. can drag Lebanon into the pro-Israeli orbit of the Gulf will not last long and may cost the Lebanese people more blood, as the country may again be pushed to the brink of civil war.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004) and ran the popular The Angry Arab blog. He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Support CN’s

Winter Fund Drive!![]()

Make a tax-deductible donation securely by credit card or check by clicking the red button:

Great run down. I often feel a deep sense of loss because of Beirut’s former position as the “Paris” of the middle east. Truly sad. perhaps I can vacation to Tangier before we find some reason to bomb it into the stone age.?