Across the Pacific, Indigenous communities lead a growing wave of sovereignty against ongoing legacies of Western colonialism in the region.

George Parata Kiwara (Ngati Porou and Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki), Jacinda’s Plan, 2021. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

For the past few weeks I have been on the road in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Australia at the invitation of groups such as Te Kuaka, Red Ant, and the Communist Party of Australia.

For the past few weeks I have been on the road in Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Australia at the invitation of groups such as Te Kuaka, Red Ant, and the Communist Party of Australia.

Both countries were shaped by British colonialism, marked by the violent displacement of native communities and theft of their lands. Today, as they become part of the U.S.-led militarisation of the Pacific, their native populations have fought to defend their lands and way of life.

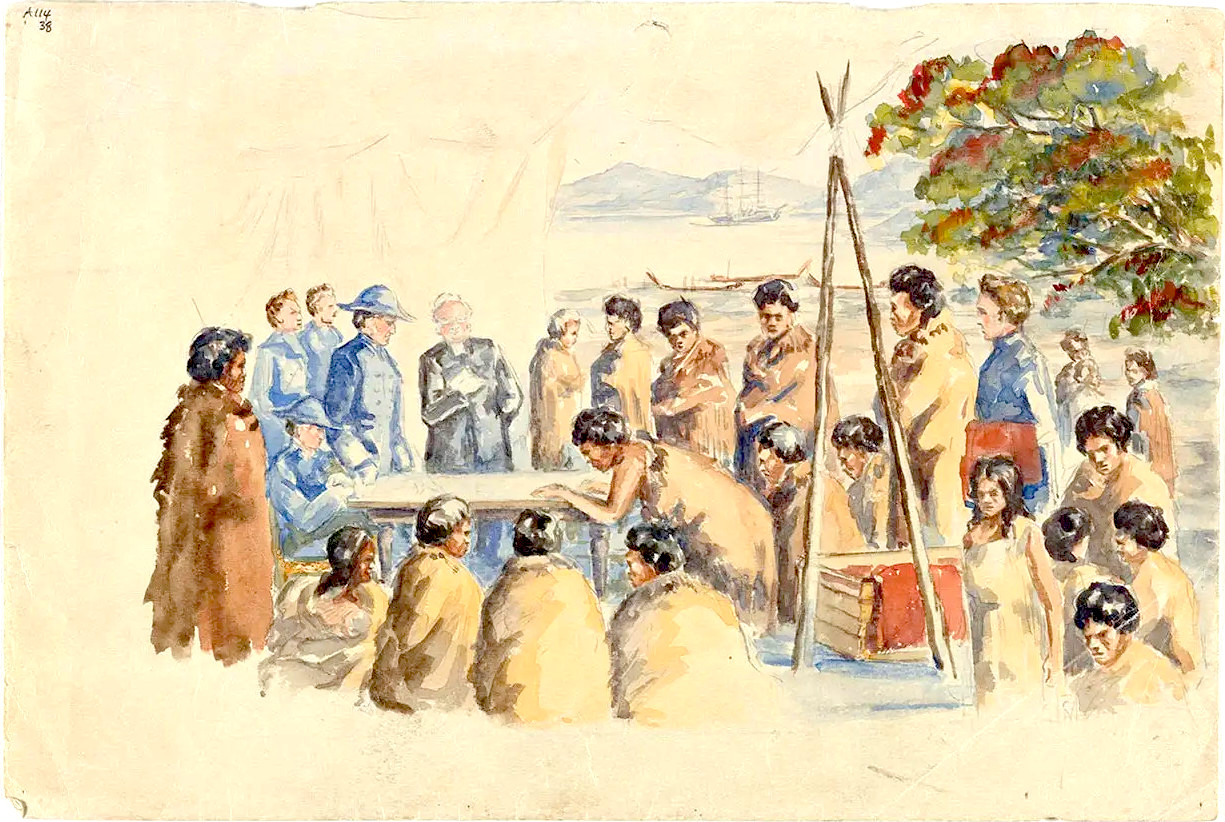

On Feb. 6, 1840, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (the Treaty of Waitangi) was signed by representatives of the British Crown and the Maori groups of Aotearoa. The treaty (which has no point of comparison in Australia) claimed that it would “actively protect Maori in the use of their lands, fisheries, forests, and other treasured possessions” and “ensure that both parties to [the treaty] would live together peacefully and develop New Zealand together in partnership.”

While I was in Aotearoa, I learned that the new coalition government seeks to “reinterpret” the Treaty of Waitangi in order to roll back protections for Maori families. This includes shrinking initiatives such as the Maori Health Authority (Te Aka Whai Ora) and programmes that promote the use of the Maori language (Te Reo Maori) in public institutions.

The fight against these cutbacks has galvanised not only the Maori communities, but large sections of the population who do not want to live in a society that violates its treaties.

When Aboriginal Australian Sen. Lidia Thorpe disrupted the British monarch Charles’ visit to the country’s Parliament last month, she echoed a sentiment that spreads across the Pacific, yelling, as she was dragged out by security:

“You committed genocide against our people. Give us our land back! Give us what you stole from us – our bones, our skulls, our babies, our people. … We want a treaty in this country. … You are not my king. You are not our king.”

Oriwa Tahupotiki Haddon (Ngati Ruanui), “Reconstruction of the Signing of the Treaty of Waitangi,” c. 1940. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

With or without a treaty, both Aotearoa and Australia have seen a groundswell of sentiment for increased sovereignty across the islands of the Pacific, building on a centuries-long legacy.

This wave of sovereignty has now begun to turn towards the shores of the massive U.S. military build-up in the Pacific Ocean, which has its sights set on an illusionary threat from China.

U.S. Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall, speaking at a September 2024 Air & Space Forces Association convention on China and the Indo-Pacific, represented this position well when he said, “China is not a future threat. China is a threat today.” The evidence for this, Kendall said, is that China is building up its operational capacities to prevent the United States from projecting its power into the western Pacific Ocean region.

For Kendall, the problem is not that China was a threat to other countries in East Asia and the South Pacific, but that it is preventing the U.S. from playing a leading role in the region and surrounding waters – including those just outside of China’s territorial limits, where the U.S. has conducted joint “freedom of navigation” exercises with its allies.

“I am not saying war in the Pacific is imminent or inevitable,” Kendall continued. “It is not. But I am saying that the likelihood is increasing and will continue to do so.”

Christine Napanangka Michaels (Nyirripi), “Lappi Lappi Jukurrpa” or “Lappi Lappi Dreaming,” 2019. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

In 1951, in the midst of the Chinese Revolution (1949) and the U.S. war on Korea (1950–1953), senior U.S. foreign policy advisor and later Secretary of State John Foster Dulles helped formulate several key treaties, such as the 1951 Australia, New Zealand, and United States Security (ANZUS) Treaty, which brought Australia and New Zealand firmly out of British influence and into the U.S.’s war plans, and the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, which ended the formal U.S. occupation of Japan.

These deals – part of the U.S.’s aggressive strategy in the region – came alongside the U.S. occupation of several island nations in the Pacific where the U.S. had already established military facilities, including ports and airfields: Hawaii (since 1898), Guam (since 1898), and Samoa (since 1900).

Out of this reality, which swept from Japan to Aotearoa, Dulles developed the “island chain strategy,” a so-called containment strategy that would establish a military presence on three “island chains” extending outward from China to act as an aggressive perimeter and prevent any power other than the U.S. from commanding the Pacific Ocean.

Over time, these three island chains became hardened strongholds for the projection of U.S. power, with about four hundred bases in the region established to maintain U.S. military assets from Alaska to southern Australia.

Despite signing various treaties to demilitarise the region (such as the South Pacific Nuclear Free Treaty, also known as the Treaty of Rarotonga in 1986), the U.S. has moved lethal military assets, including nuclear weapons, through the region for threat projection against China, North Korea, Russia, and Vietnam (at different times and with different intensity).

This ‘island chain strategy’ includes military installations in French colonial outposts such as Wallis and Futuna, New Caledonia, and French Polynesia. The U.S. also has military arrangements with the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau.

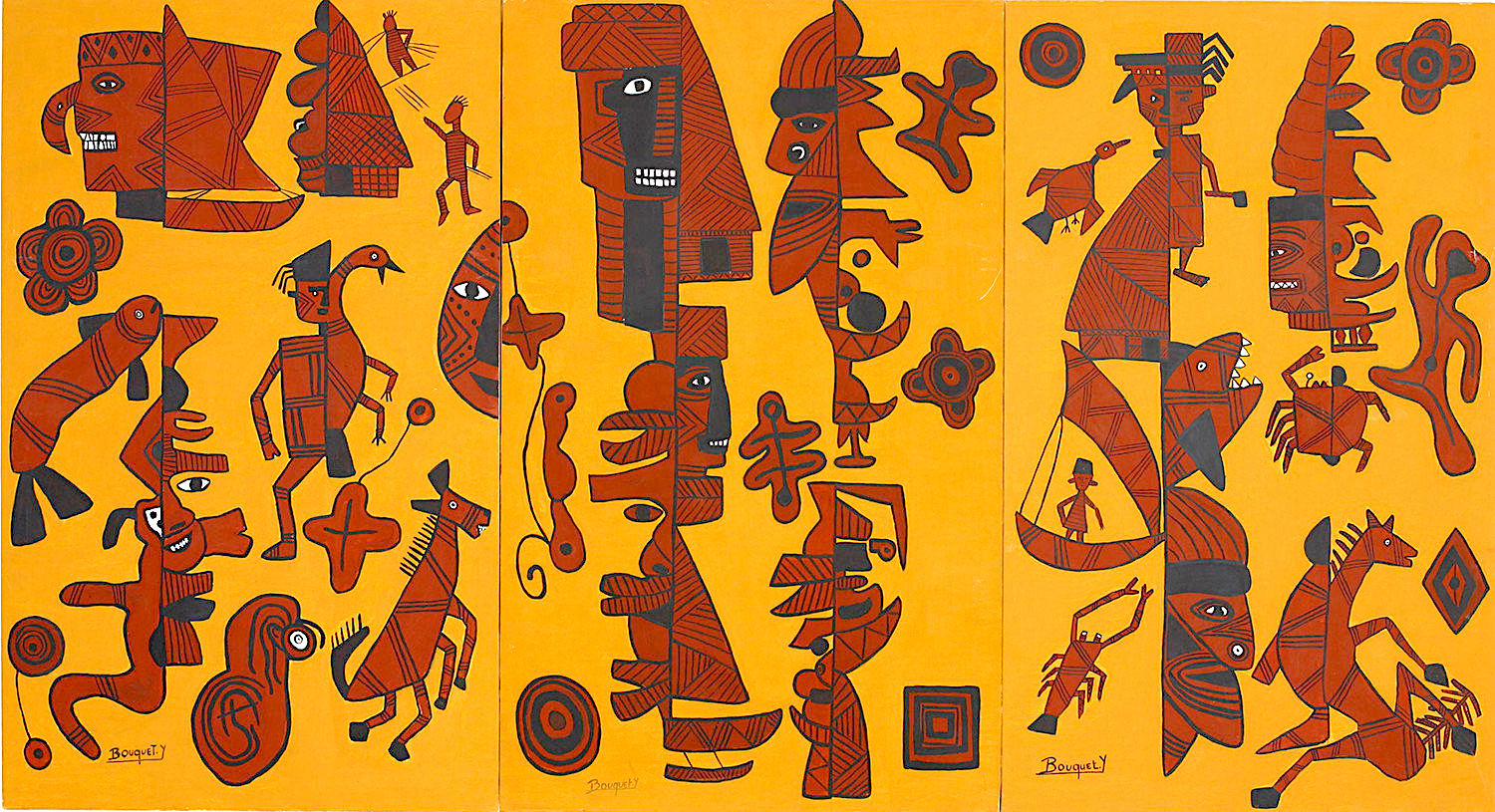

Yvette Bouquet, Kanak, Profil art, 1996. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

While some of these Pacific Island nations are used as bases for U.S. and French power projection against China, others have been used as nuclear test sites.

Between 1946 and 1958, the U.S. conducted sixty-seven nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands. One of them, conducted in Bikini Atoll, detonated a thermonuclear weapon a thousand times more powerful than the nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Darlene Keju Johnson, who was only three years old at the time of the Bikini Atoll detonation and was one of the first Marshallese women to speak publicly about the nuclear testing in the islands, encapsulated the sentiment of the islanders in one of her speeches: “We don’t want our islands to be used to kill people. The bottom line is we want to live in peace.”

Walangkura Napanangka, Pintupi, Johnny Yungut’s Wife, Tjintjintjin, 2007. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

Yet, despite the resistance of people like Keju Johnson (who went on to become a director in the Marshall Islands Ministry of Health), the U.S. has been ramping up its military activity in the Pacific over the past fifteen years, such as by refusing to close bases, opening new ones, and expanding others to increase their military capacity.

In Australia – without any real public debate – the government decided to supplement U.S. funding to expand the runway on Tindal Air Base in Darwin so that it could house U.S. B-52 and B-1 bombers with nuclear capacity. It also decided to expand submarine facilities from Garden Island to Rockingham and build a new high-tech radar facility for deep-space communications in Exmouth.

These expansions came on the heels of the Australia-United Kingdom-United States (AUKUS) partnership in 2021, which has allowed the U.S. and the U.K. to fully coordinate their strategies.

The partnership also sidelined the French manufacturers that until then had supplied Australia with diesel-powered submarines and ensured that it would instead buy nuclear-powered submarines from the U.K. and U.S.. Eventually, Australia will provide its own submarines for the missions the U.S. and U.K. are conducting in the waters around China.

Over the past few years, the U.S. has also sought to draw Canada, France, and Germany into the U.S. Pacific project through the U.S. Pacific Partnership Strategy for the Pacific Islands (2022) and the Partnership for the Blue Pacific (2022).

In 2021, at the France-Oceania Summit, there was a commitment to reengage with the Pacific, with France bringing new military assets into New Caledonia and French Polynesia. The U.S. and France have also opened a dialogue about coordinating their military activities against China in the Pacific.

Jef Cablog, Cordillera, Stern II, 2021. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

Yet these partnerships are only part of the U.S. ambitions in the region. The U.S. is also opening new bases in the northern islands of the Philippines – the first such expansion in the country since the early 1990s – while intensifying its arm sales with Taiwan, to whom it is providing lethal military technology (including missile defence and tank systems intended to deter a Chinese military assault).

Meanwhile the U.S. has improved its coordination with Japan’s military by deciding to establish joint force headquarters, which means that the command structure for U.S. troops in Japan and South Korea will be autonomously controlled by the U.S. command structure in these two Asian countries (not by orders from Washington).

However, the U.S.-European war project is not going as smoothly as anticipated. Protest movements in the Solomon Islands (2021) and New Caledonia (2024), led by communities who are no longer willing to be subjected to neocolonialism, have come as a shock to the U.S. and its allies.

It will not be easy for them to build their island chain in the Pacific.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and, with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

This article is from People’s Dispatch and was produced by Globetrotter.

Views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

I used to think that the best orator in the English language was George Galloway, whose first language was of course English despite him being Scottish.

I am now rethinking that, after hearing this speech by Vijay Prashad whose first language was Bengali, second language Hindi and third language English.

hxxps://www.listennotes.com/podcasts/the-red-kelly-cast/ep-09-the-process-of-T4zn6BP73GO/

Vijay tends to deliver his speeches extemporaneously, no teleprompter required, unlike the uniformly feeble minded “leaders of the free world”

“Aotearoa (New Zealand)”

This country is still called New Zealand. its name has never been, and is not now, “Aotearoa”. Prior to the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, this country had no name, because it was not, and had never been, a polity. Chiefs ruled over tribal areas only, and such other areas as they’d acquired by means of conquest. Such areas were relatively small: this isn’t a large landmass. The Maori translation of the English-language Treaty uses Niu (or Nu) Tirani for NZ: very clearly a transliteration of “New Zealand”.

““ensure that both parties to [the treaty] would live together peacefully and develop New Zealand together in partnership.””

The Treaty says no such thing. Moreover, no 19th century monarch would have contemplated an arrangement such as partnership with her subjects. And while we’re talking about the Treaty, it contains no principles, either. This nonsense about partnership and principles is a piece of 1980s revisionism: I remember when all of that happened.

In the 1970s, when I was a young adult, I learned the Maori language to a fair degree of fluency; I was taught by a native speaker, of whom there were at that time still many, at least in rural areas. Thus I have read the Treaty in both languages.

“…the new coalition government seeks to “reinterpret” the Treaty of Waitangi….”

This isn’t so. Had you read the proposed Bill, you would know this.

“…. in order to roll back protections for Maori families. This includes shrinking initiatives such as the Maori Health Authority (Te Aka Whai Ora) and programmes that promote the use of the Maori language (Te Reo Maori) in public institutions. ”

The Maori Health Authority was not only a priori racist and undemocratic, it was hugely expensive and unnecessary. People don’t differentially get sick because they’re Maori: that’s patronising and ridiculous. Note that the Maori language is lost, on account of there being very few to no native speakers, most native speakers now being very old. I am not myself Maori, but, like many old Pakeha (white) families here, we have Maori in our extended family. None of them is a native speaker, though one of them is bilingual. Which won’t save the language, unfortunately. It will survive for a while longer, but without native speakers, it’s ultimately doomed to extinction.

“…. both Aotearoa and Australia have seen a groundswell of sentiment for increased sovereignty….”

Both NZ and Australia are independent countries. Neither has been a colony since the 19th century. In fact, NZ was originally a colony of NSW, but the 1852 Constitution Act granted it self-government. At that time, voting was restricted to British men, and the landholding qualification applied. Maori men got the vote in 1867 – when the Maori seats were created. All women – including Maori – got the vote in 1893. So at least in NZ, democracy is deeply embedded.

“Protest movements in the Solomon Islands (2021) and New Caledonia (2024), led by communities who are no longer willing to be subjected to neocolonialism….”

As I recall, the Solomons allowed the building of a Chinese base, which really annoyed the US and Australia. With regard to New Caledonia (a semi-autonomous French territory), the Kanak uprising resulted from Paris proposing a tweak to the voting laws, which would allow non-indigenous citizens (up to a fifth of the population) to vote in provincial elections. Unless they or their ancestors had been resident in NC before 1998, non-indigenes have been prevented from voting, a situation that would be seen as egregiously undemocratic here in NZ. The situation is still very tense in NC, I believe. The uprising has been catastrophic for the local economy, depending so much as it does on tourism.

So: neither case was directly related to US adventurism in the Pacific.

It would be a mistake to conclude that many of us who are the descendant of western settlers aren’t very concerned by US sabre-rattling in this part of the world. We in NZ are well aware that China is our largest trading partner. We need US/UK/whoever aggression in the southwest Pacific like we need toothache. But there are difficulties: this is a small polity, with scant means to defend itself. As we know only too well, the major western powers aren’t above a bit of slapping around (so to speak) when they think we’ve got above ourselves.

I read a lot of other great reporters, and know their takes and what I will hear, but your articles are exceptional in that they take us off the beaten trail into areas not otherwise covered. Appreciate learning so much more about the rest of the world. Colonialism is diminishing with every rising up against it. Don’t you think BRICS will be a great encouragement, for one thing, just to get rid of the devastation of Sanctions on 60% of the poor of those targeted countries. Uplifting to hear of the defiance in the Islands.

Britain, the USA and Australia have a long history of ignoring indigenous populations in the South Pacific. They do not like to recognize that these people really exist. Consequent to that, they do not understand that these people will be an active military force against them in time of war.

NATO’s future war with China is not the war of Pacific Islanders, not the war of New Zealanders and not the war of most Australians.