The recent Supreme Court decision granting presidents nearly absolute immunity for official acts leaves fewer guardrails to prevent Trump from abusing his authority, writes Marjorie Cohn.

Donald Trump at a campaign rally in Phoenix in June. (Gage Skidmore, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

“The next time, I’m not waiting” before committing troops to suppress protests, Trump said at a rally in 2023.

“The next time, I’m not waiting” before committing troops to suppress protests, Trump said at a rally in 2023.

Employing federal troops to suppress domestic protests and deport immigrants from U.S. soil en masse would be illegal, but Donald Trump has been pushing to do so since his first administration. The recent Supreme Court decision granting presidents nearly absolute immunity for official acts has created a situation with far fewer guardrails to prevent Trump from abusing his authority in his second presidential term.

Trump and his allies have reportedly drafted plans for him to deploy the military against civil demonstrators on his first day in office, according to a Washington Post report from November 2023. And Trump, who promised to carry out the largest deportation effort in U.S. history, has also indicated that he will use the military to deport millions of undocumented immigrants.

When Fox News asked Trump whether he thought “outside agitators” might have an effect on Election Day, Trump responded by saying, “I think the bigger problem is the enemy from within.”

He added, “We have some very bad people. We have some sick people, radical left lunatics. And I think they’re the big — and it should be very easily handled by, if necessary, by National Guard, or if really necessary, by the military, because they can’t let that happen.”

During his campaign, Trump also said that if re-elected, he would use the military at the southern border and to enforce the law in cities like Chicago and New York, which he dubbed “crime dens.”

Trump’s prior time in office shows that his willingness to raise such threats goes beyond campaign rhetoric.

After massive demonstrations erupted around the country in protest against the May 25, 2020, murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police, then-President Trump told his Secretary of Defense Mark T. Esper and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Mark A. Milley that he wanted to invoke the Insurrection Act — which allows the president to deploy the military domestically and use it for civilian law enforcement — and order “ten thousand troops in Washington to get control of the streets.”

On June 1, 2020, Trump said, “If a city or state refuses to take the actions that are necessary to defend the life and property of their residents, then I will deploy United States military and quickly solve the problem for them.”

Minnesota State Patrol troopers in riot gear on May 29, 2020, following the publication of a video showing a white Minneapolis police officer kneeling on the neck of George Floyd, a handcuffed and unarmed Black man, and killing him. (Tony Webster, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons)

Esper and Milley objected, saying the turmoil was best handled by civil law enforcement and the D.C. National Guard. Trump was furious. He called his top military leaders “losers” and repeated his wish to send active-duty troops into Minneapolis. “Can’t you just shoot them?” he asked Milley. “Just shoot them in the legs or something?”

Trump also proposed sending federal troops into Chicago, Seattle and Portland in response to Black Lives Matter protests and once again, Esper and Milley, joined by then-Attorney General William Barr, talked him out of it.

state patrolled by the U.S. military,” according to Dickinson.

[See: “Trump Threatens to Grab Protestors By the Posse”]

A former senior Defense Department official who served in the first Trump administration said that federal forces could be sent to U.S. cities to assist with Trump’s mass deportation plan once he is inaugurated.

During his second term, Trump will not likely be deterred from using the military against protesters and immigrants, even though employing federal troops to enforce domestic law in this manner would be illegal.

The Posse Comitatus Act, enacted in 1878 to end the use of federal troops in overseeing elections in the post–Civil War South, bars the use of the military to enforce domestic laws, including immigration law.

The Posse Comitatus Act, which forbids the willful use of “any part of the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, or the Space Force as a posse comitatus [power of the county] or otherwise to execute the laws.” The only exceptions to the Posse Comitatus Act’s prohibition are “in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress.”

‘Serious Risk of Abuse’ of Insurrection Act

The Insurrection Act carves out an exception to the Posse Comitatus Act. The Insurrection Act can be used to authorize the president to deploy the U.S. armed forces, federalize the National Guard, or deputize private militias of nongovernmental forces within the United States.

There are three sections of the Insurrection Act that the president could invoke, only one of which requires the consent of state officials:

-

First, where the legislature or governor of a state asks the president for assistance to quell an insurrection against the government (section 251);

-

Second, where the president decides that “unlawful obstructions, combinations, or assemblages, or rebellion against the authority of the United States,” render it “impracticable” to enforce U.S. or state law in the courts (section 252); or

-

Third, when “any insurrection, domestic violence, unlawful combination, or conspiracy” deprives people of a legal right, privilege, immunity, or protection, that results in the denial of Equal Protection or “opposes or obstructs the execution of the laws of the United States or impedes the course of justice under those laws” (section 253).

Most of the instances in which the Insurrection Act has been invoked occurred under section 251. The Act was last used in 1992, when then-California Gov. Pete Wilson asked President George H.W. Bush to deploy federal troops to put down the uprising against anti-Black racism and police brutality in Los Angeles that followed the state acquittal of the police officers who beat Rodney King.

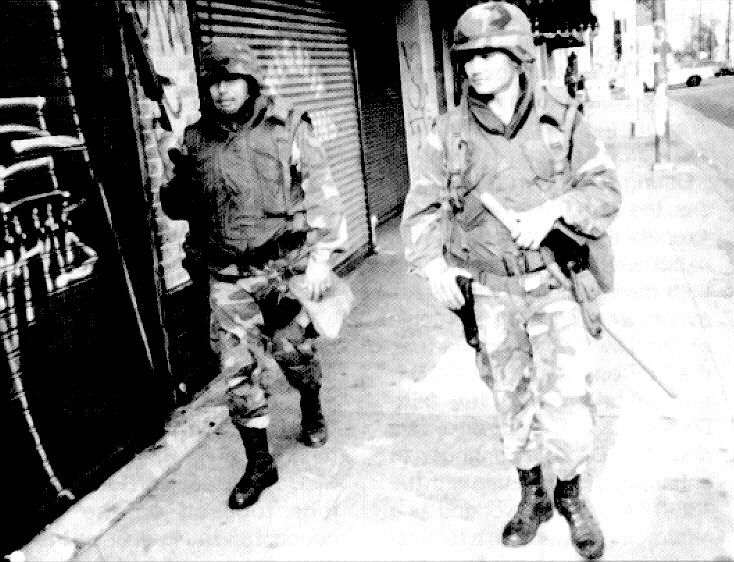

National Guard soldiers patrolling Los Angeles in April 1992. (US Army Field Artillery School, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Section 252 of the Insurrection Act can be triggered by the president’s subjective belief that it is “impracticable” for the courts and criminal legal system to function properly. Although courts would hesitate to overrule a president’s subjective decision, service members could decide that his order was illegal and refuse to obey it.

Section 253 of the Insurrection Act was enacted after the Civil War to ensure that Southern states enforced the federal rights of Black people. President John F. Kennedy used this section in 1962 and 1963 to send federal troops to Mississippi and Alabama to enforce the civil rights laws.

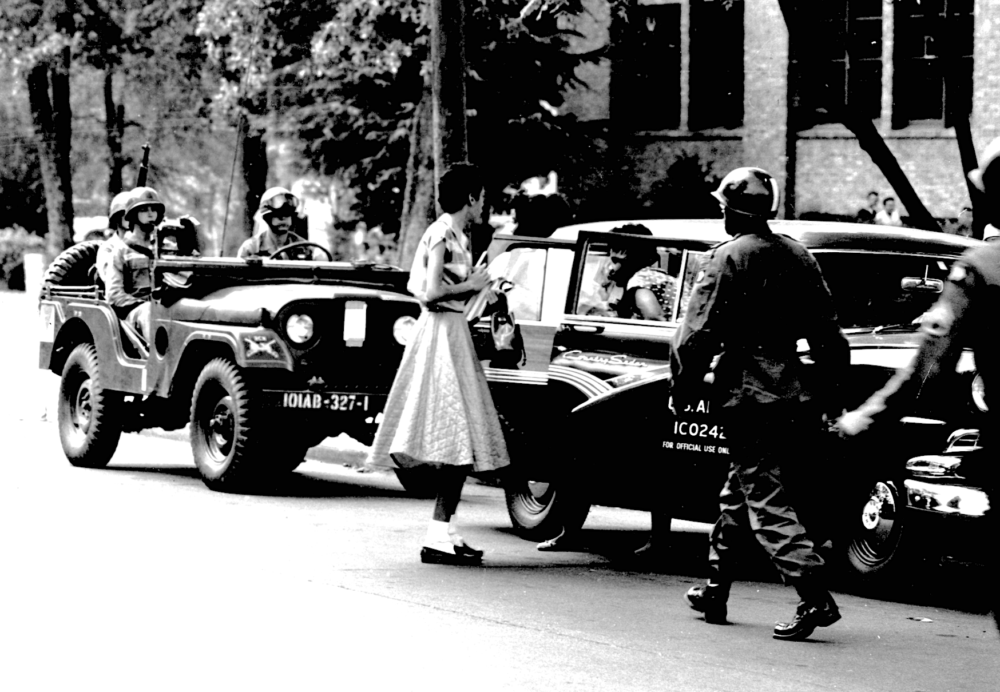

In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower deployed troops to desegregate schools in Little Rock, Arkansas, consistent with section 253. And in 1965, President Lyndon Johnson used section 253 to protect civil rights demonstrators from police violence during the civil rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

101st Airborne escorting the Little Rock Nine to school in September 1957. (U.S. Army, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

The Insurrection Act does not authorize the president to deploy federal troops on U.S. soil to “restore public order,” Harold Hongju Koh and Michael Loughlin explained for the American Constitution Society in 2020.

As Laura Dickinson writes at Lawfare, executive branch lawyers — including members of Trump’s past administration — have previously made the case that the language of the Insurrection Act should be construed narrowly and used only as a “last resort” to avoid running afoul of the 14th Amendment; the Supremacy Clause (which says federal law trumps state law when there is a conflict); and Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution, which requires the federal government to protect a state against “domestic violence.”

Section 253 is “particularly broad and vague,” Dickinson notes. It could encompass a small demonstration that interferes with law enforcement activities or judicial proceedings, “so long as there were a conspiracy to do so by two or more persons.”

“The Insurrection Act, if deployed without restraint, could ultimately transform a constitutional democracy into a police

“Trump’s threat to use U.S. military forces domestically against protesters, immigrants and other ‘enemies,’ places servicemembers in a legal and ethical dilemma,” Kathleen Gilberd, executive director of the National Lawyers Guild’s Military Law Task Force, told Truthout.

“Soldiers have not only a right, but a duty, to refuse illegal orders; yet the legality of those orders would be determined by courts-martial of refusers. And servicemembers have a moral obligation not to harm the innocent; yet such harm would be inevitable if troops are used against civilians here.”

The Uniform Code of Military Justice requires that all military personnel obey lawful orders. A law that violates the Constitution or a federal statute is an unlawful order. Both the Army Field Manual and the Nuremberg Principles create a duty to disobey unlawful orders.

Proposed Reform of Insurrection Act

In April 2024, at the invitation of the American Law Institute, a bipartisan group led by Bob Bauer, professor at NYU School of Law and former White House Counsel to President Barack Obama, and Jack Goldsmith, professor at Harvard Law School and former Assistant Attorney General in the George W. Bush administration, issued “Principles for Insurrection Act Reform.”

“There is agreement on both sides of the aisle that the Insurrection Act gives any president too much unchecked power,” Goldsmith said.

The bipartisan group proposed amending the Insurrection Act to say the president cannot deploy the armed forces unless “the violence [is] such that it overwhelms the capacity of federal, state, and local authorities to protect public safety and security.”

The main points of reform proposed by the bipartisan group this April would:

-

Require the president to consult with the governor before deploying troops into any state;

-

Require the president to report to Congress within 24 hours of deployment about the need to invoke the Insurrection Act and about consultations held with state authorities;

-

Limit the president’s authority to deploy troops under the Act to a maximum of 30 days unless Congress renews authorization; and

-

Establish a fast-track process for Congress to vote on renewal of presidential authority under the Insurrection Act.

However, the Principles for Insurrection Act Reform document states that Insurrection Act reform “need not and should not include a provision for judicial review.” This appears to be a compromise reached to achieve bipartisan consensus.

On the other hand, S. 4699, titled the “Insurrection Act of 2024,” which was introduced by Sen. Richard Blumenthal in July, does contain a provision for judicial review. It provides that any individual or state or local government that is injured by, or has a credible fear of injury from, the deployment of the armed forces may bring a civil lawsuit for declaratory or injunctive relief in the U.S. district court.

The Supreme Court would have jurisdiction to hear an appeal from the decision of the district court. Given the current political climate, prospects for reform of the Insurrection Act are slim to none.

‘The Next Time, I’m Not Waiting’

Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington, a nonprofit watchdog group, analyzed more than 13,000 of Trump’s Truth Social posts from Jan. 1, 2023, to April 1, 2024, and discovered that he pledged at least 19 times to weaponize law enforcement, including several branches of the military, against civilians.

An investigation by Military.com found that few checks would exist on a president who illegally orders the military to be used against U.S. citizens, particularly when he invokes the Insurrection Act.

The intent behind the Insurrection Act is to allow the president to use the military to help civilian law enforcement authorities “when they are overwhelmed by an insurrection, rebellion, or other civil unrest, or to enforce civil rights laws when state or local governments can’t or won’t enforce them,” Joseph Nunn wrote at Slate.

“In such cases, a narrow exception to the general rule against using the military for law enforcement makes good sense,” he added. “The problem is that the Insurrection Act creates a giant loophole in the Posse Comitatus Act rather than a limited exception to it.” The “central failing” of the Insurrection Act “is that it grants virtually limitless discretion to the president.”

Trump expressed regret at not using the Insurrection Act in the aftermath of the summer 2020 Black Lives Matter protests. “The next time, I’m not waiting,” he declared at a rally in November 2023.

“It’s very likely that you will have the Trump administration trying to shut down mass protests — which I think are inevitable if they were to win — and to specifically pick fights in jurisdictions with blue-state governors and blue-state mayors,” ACLU Executive Director Anthony Romero said in August.

“There’s talk that he would try to rely on the Insurrection Act as a way to shut down lawful protests that get a little messy. But isolated instances of violence or lawlessness are not enough to use federal troops,” Romero said.

Lee Gelernt, an ACLU attorney, told The Washington Post that members of the organization “are particularly concerned about the use of the military to round up immigrants,” predicting that a second Trump term “will be much worse” than his first administration.

“As always, we will go to court to challenge illegal policies, but it is equally essential that the public push back, as it did with family separation,” he said.

Regardless of the illegality of Trump’s threatened abuse of the Insurrection Act, the Supreme Court has recently granted almost absolute immunity to presidents for official acts.

The ACLU is already drafting legal challenges to Trump’s invocation of the Insurrection Act against protesters.

Marjorie Cohn is professor emerita at Thomas Jefferson School of Law, dean of the People’s Academy of International Law and past president of the National Lawyers Guild. She sits on the national advisory boards of Assange Defense and Veterans For Peace and is the U.S. representative to the continental advisory council of the Association of American Jurists. Her books include Drones and Targeted Killing: Legal, Moral and Geopolitical Issues.

This article is from Truthout and reprinted with permission.

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Aren’t we forgetting (already!) Biden’s Department of Defense directive 5240.01 issued on September 27, 2024 that allows the US military to use lethal force against American citizens in assisting police authorities in domestic disturbances? We might also look to 1794 when President Washington assembled a militia force 12,000 men strong to intimidate tax rebels in western Pennsylvania, in the “Whiskey Rebellion.” This was in fact the first exercise of the Second Amendment, which was codified into law in the 1792 Militia Act.

We are STILL in COG – Continuity of Government

Four Kinds of Presidents

Non-President – Joe Biden – Elected during COG Continuity of Government – Null & Void – Was never a President

Sitting President – Vacant – Implementation of COG by a Sitting President vacates this office

Continuity of Government President – Donald Trump (see video) – Stepped aside when COG activated – The Military is in charge

President Elect – Donald Trump – Elected during COG Continuity of Government – Null & Void – But waiting to be reinstated when/if COG is deactivated

If COG IS NOT deactivated, Donald Trump is a COG President and will APPEAR to be a sitting President

hxxps://rumble.com/v5jfybx-cog-continuity-of-government-proof-it-is-active-now.html

Read everything in the Rumble comments

THE LAW OF WAR SUPERSEDES CONGRESS. DO NOT FORGET THAT.

I don’t understand the sudden panic on the left.

Or do I?

Trump’s predecessors of both parties have expanded executive powers through EOs.

Congress has let them do it.

Did Cohn make a peep when Biden defied the SCOTUS regarding student loans?

When the Biden administration and its minion Anthony Fauci put a brake on the US economy and imposed dodgy untested jabs on millions of citizens?

Where does Cohn stand on illegal migrants pouring over the border ?

On mayors and governors in blue states scoffing at federal law by proclaiming “sanctuary cities,” —to the detriment of their local working classes and poor?

On BLM rioting in numerous US cities?

On lawfare and the weaponization of the DOJ and intel agencies in an effort to undermine President Trump during his first administration?

The egregious activities of Biden and his crime family?

Did Cohn stand up for Trump’s own civil liberties and human rights?

If so, I missed it.

This article is all theoretical partisan squawking.

Trump won the election because he promised to deal with several areas of lawlessness in American life.

Trump won. Get over it.

The more liberals squawk their partisan panic the lessseriously anyone takes them.

.

Aspects of the Big Bad Trumpenstein’s admin will be painful, no doubt. His regime’s designs on Palestine and Iran are likely going to be what nightmares are made of.

But let’s not forget that it’s under the Zients administration that the most disgusting genocide of the past several decades is unfolding, campus protesters were beaten and jailed, and graduates with integrity who spoke out against Israeli slaughters were put on “do not hire” blacklists by Zionist Wall Street flunkies.

Moreover, under the Klain regime we were put on the brink of World War 3 by waging a dumb and very dangerous proxy war on Russia’s border.

Who has forgotten that?

I’d wager a lot of petty bourgeois liberals with acute TDS already have or are about to very soon.

Trump’s a symptom of our diseased socio-economic-politico reality, not the cause.

What is Zients?

The real prez of the United States right now.

(Crash Test Dummy’s Chief of Staff.)

And what is Klain?

Biden’s Chief of Staff for the first couple of years.

If Trump uses said tactics it will also be against his own supporters many of whom do not support a gencocide.

The lies and hypocrisy are over the top as usual: where is Elon the Oligarch and the rest of the “free speech” hypocrites?

And millions of gullible, desperate and lazy US folks “voted” for Genocide.

And people still make pathetic excuses, and continue to support the Orange Saviour as if he is Jesus Christ himself. Insane.

Now, if you don’t like your public resources being sent over to mass murder women and children, while the US becomes a failed state, you got what you asked for. If you voted for Ds or Rs, you support this, so don’t complain. If you don’t like your civil liberties being pissed on and abused, don’t complain.

If the supporters of Ds and Rs are honest they would applaud the genocide, applaud sending 10s of billions to Israel, applaud the oligarchy and celebrate the housing crisis, health care crisis, debt peonage crisis, environmental crisis. Celebrate the institutional corruption, flagrant abuses of power, violation of civil rights etc. But lies and hypocrisy are considered virtues in US mainstream culture. So the DT supporters will make more pathetic excuses for the next 4 years, and the Ds will blame their crimes on their Country Club colleagues, the Rs.

Well-said!

Governors have Constitutional authority to use the National Guard in the event of an invasion. Art I, Sec 8, cl 12-16.

The “double standard” at play once again. Apparently Trump didn’t think the riot against the capital deserved the troops to be deployed against them, but everyone else better behave themselves according to him. We live in a society of “we are right and the others are wrong – period, end of discussion.”

I am no Trump fan, but I do agree with Trump when he says “I think the bigger problem is the enemy from within.” We have had to live with that “bigger problem” for the past 4 years. Law and Order are not bad things, but they are meaningless unless they are enforced, in a lawful and orderly way.

That saying has been around for many years. In fact there is a book called that and a few years later (2019) they made a short-lived TV series called that.

Not a D or an R but pretty sure I and most of my friends and family qualify as “enemies within.” kind of sad that people here…again… seem to think anything good will come out of this. they trumpies probably with end the proxy war in Ukraine but maybe not in a particularly benign fashion. They will probably also escalate the fking over of our former friends the Kurds.

It never stops being funny to me, the way every brain dead idiot in this country , thinks that the fascist government and it’s orange head is totally working for, and loves the shit out of him/her.

Thank You Marjorie

Hang onto your hats folks – it’s going to be a bumpy ride!

Trump couldn’t have granted himself these powers but Biden could have.

Sad time for America when an actual piece of shit has been elected president.

Nothing new. He’s just the latest in a long line: Anyone who supports stealing our public resources and giving it away for free to a foreign country to commit genocide is much worse than “an actual piece of shit” IMO. BOTH the Ds and Rs are in lockstep on this, so what do we expect? All three branches of govt. are giant cesspools of institutional corruption at this stage in the imperial decline.

The declining empire is producing unfit geriatric kakistocrats: cognitively-challenged, unhinged, freakish caricatures. Kinda like the late western Roman Empire. Commodus, Caracalla, or Honorius might be good general comparisons, although not geriatrics like JB or DT.