The author looks back on the slain Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, on the times he interviewed him and the impact on the region of his killing.

Hassan Nasrallah during a discussion with Iranian officials in 2019. (Khamenei.ir, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

By As`ad AbuKhalil

Special to Consortium News

There is no doubt that leaders do matter in the life of nations and movements, no matter how much one must acknowledge the role played by the masses of ordinary, working people.

There is no doubt that leaders do matter in the life of nations and movements, no matter how much one must acknowledge the role played by the masses of ordinary, working people.

The death of Egyptian President Gamal Abdul Nasser in 1970 changed the political landscape in the region forever and helped launch what is commonly dubbed the “Saudi era” (i.e., the domination of Saudi Arabia over the affairs of the Arab world).

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s impact on the Arab-Israeli question has been, perhaps, bigger than Nasser’s because he has been more effective — from the standpoint of the Arab struggle against Israeli aggression and occupation — in his understanding and containment of the Israeli threat towards Lebanon and Palestine.

Nasser lost lands to Israel in war while Nasrallah played a major role in the liberation of South Lebanon in 2000 — without making any concessions to Israel.

It is premature to assess the impact of the passing of somebody with Nasrallah’s stature and influence on Arab politics, particularly on the Palestinian problem. But it is certain that the region will not be the same after his passing.

Such was his impact that Western and Gulf governments devoted billions of dollars to undermine his popularity throughout the region. Since the July 2006 war (when Israel was humiliated in the battlefield, and when the UAE and Saudi Arabia were on the side of Israel), the Western-Israeli-Gulf alliance worked to undermine Hezbollah and its leader.

Arab media were devoted to the one purpose of combatting Nasrallah and placing him in a purely sectarian corner, presenting him as an Iranian puppet (when in reality he was a full decision-maker with his Iranian allies. In pictures with the U.S.-assassinated Iranian Gen. Qassim Suleimani, for instance, the latter was clearly his junior in rank). There is no doubt that leaders in the life of nations and movements matter

The Emergence of Nasrallah

Nasrallah, center, with Iranian leader Ali Khamenei, left, and Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps commander Qassem Soleimani, right, in undated photo, circa 2019. (Khamenei.ir, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

Nasrallah owes his emergence to hard will and determination that later characterized his leadership. It began with his involvement with comrades in 1982 when they split from the Amal movement to form a new organization that came to full fruition in 1985 with the official declaration of Hezbollah as a new political-military organization.

There were disparate groups before 1985 that would later come together as one party. In 1982, assisted by the Iranian government and its Revolutionary Guards, these groups of Lebanese Shiites (and they were only tens in numbers) decided to reject the order that Israel was trying to impose on Lebanon.

Those anonymous groups at that time pushed Israel south of Beirut and drove U.S. troops from Lebanon after killing 220 American marines in an attack on their barracks on Oct. 23, 1983. According to Ronald Reagan, they were “redeployed” in February 1984. (The U.S. consoled itself by invading the tiny Caribbean country of Grenada on Oct. 25, 1983, two days after the attack on the barracks.)

Born Into Poverty

Nasrallah was born to an impoverished family from a village in South Lebanon near Tyre. But he grew up in east Beirut in a very poor Shiite neighborhood east of the capital. His father was a grocer and unbeknownst to many, was not religious but rather a secular supporter of the Syrian Social National Party (a secular, progressive, political party dedicated to the liberation of Palestine and the unification of Greater Syria).

The family was forced out of East Beirut by Israeli-armed and supported right-wing militias who perpetrated campaigns of sectarian and ethnic cleansing against Muslims and Palestinians. The family resettled in the southern suburbs of Beirut, the same area where he was killed by an Israeli airstrike on Friday.

He was known as a serious student who decided early on to specialize in religious studies. He went, without much money, to the Shiite religious schools of Najaf, where he was taken under Abbas Musawi’s wing, a more senior religious student who would serve for much of his life as Nasrallah’s mentor.

Musawi would also later become the leader of Hezbollah. Nasrallah succeeded him in 1992 when the Israeli government killed Musawi with his wife and child.

In the 1980s Nasrallah became involved with the new movement that would later become Hezbollah. He held political and security positions and at one point he was chief of security for the southern suburbs of Beirut. But it was his close collaboration with military-security chief, Imad Mughniyyah that made the organization as effective for its purposes (or as dangerous and lethal to its enemies).

Nasrallah rose quickly through the ranks largely due to his high intelligence, hard work, seriousness, charisma, and it didn’t hurt that he got along very well with Mussawi, the leader of Hezbollah at the time. When Musawi was assassinated in 1992 Nasrallah was the logical choice for leader, and he has clearly left his mark and led the party in a very different direction.

It can be said that Nasrallah Lebanonized the party (in the words of Lebanese scholar, Bashir Saade) and reduced its heavy religious content, which characterized its rhetoric for much of its early history. Nasrallah persuaded his colleagues in the party to abandon once and for all the declared goal of an Islamic Republic.

He explained repeatedly to his rank and file, and to the Lebanese at large, that he came to understand that Lebanon is too diverse for any one group to dominate. It is in that sense that Nasrallah brought Hezbollah into the Lebanese political system with its advantages and disadvantages, strengths and weaknesses.

Leading by Oration

Poster of Nasrallah in Damascus in 2017. (delayed gratification, Flickr, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nasrallah’s leadership is closely tied to his speechmaking. His speech in the summer of 2006 during the war with Israel, when he told listeners to view an Israeli ship burning at sea, propelled him to a pan-Arab level not seen since the days of Nasser (that status would later suffer after the intervention in Syria).

His speech making is unique: it used a combination of techniques: classical and colloquial Arabic, and the use of humor and sarcasm. His speeches were well organized although they were often lengthy. It is through his oratorical skills that the Arab people came to know and admire Nasrallah.

I have interviewed Nasrallah several times over the years as part of my research into the organization. I first wrote about the party when I was a graduate student at Georgetown in 1985 (for an article in Middle Eastern Studies, and in which I faulted the party for stealing organizational ideas from Leninist organizations).

Replaced Leftists

My first take reflected the frustrations and even antagonism of a leftist progressive unhappy with the rise of Islamist groups who displaced communist organizations in Lebanon. It wasn’t that Hezbollah forcefully pushed them aside but the socialists and leftists suffered from many shortcomings and exhibited vast symptoms of corruption during the years of PLO dominance in Lebanon.

Furthermore, after the Israeli invasion of 1982, much of the organizations of the Lebanese National Movement (the leftist coalition) collapsed overnight and the LNM dissolved itself days after Israel invaded. The genius of Hezbollah was to go against the popular defeatist trend and to have a strong faith in the ability of this small group to bring defeat to the Israeli-American alliance in Lebanon.

I remember when I was highly critical of Hizbulalh that Edward Said and Arab nationalist thinker Clovis Maksoud spoke to me about my attitude and told me that I needed to appreciate the significance of Hezbollah’s military operations against Israel and the importance of that in historical terms for the Palestinian cause.

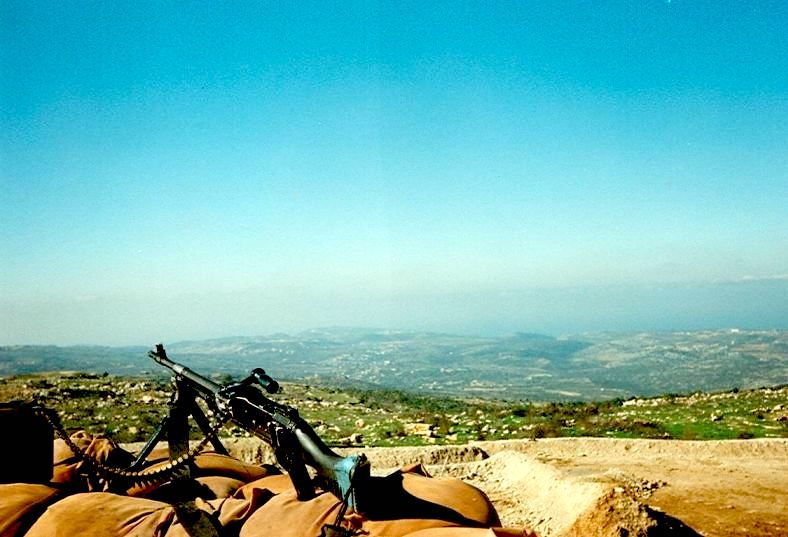

Carcom Israeli military post in Lebanon, 1998. (Oren1973, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0)

My impression of Nasrallah was that he was different from other political leaders I have met or interviewed over the years. He was more intelligent than most and certainly made himself to be the utmost expert on Israeli affairs.

He invested in the study of Israel more than any other Arab leader I know and even more than any PLO leader before him; Arafat did not know much about Israel in comparison.

I once asked Nasrallah about his daily routine of reading and he explained that his reading of Israeli affairs made his duties of religious readings suffer (although he is obligated to read regularly in that field in order to maintain his religious rank and to rise with in it).

Once after the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, I asked him a long question in which I was scathingly critical of Hezbollah’s stance and its relationship with Shiite personalities who collaborated with the American occupation.

He smiled and said:

“A few weeks ago, somebody mentioned your name in my presence and I said: Dr. As`ad is an American. Because Arabs always begin a meeting or an interview by asking about the children and the family, while you begin with a three-part question and without the common pleasantries.”

Nasrallah was humorous when most clerics in the Middle East were dour-faced and stern. I once asked him why is it that Muslim clerics rarely smile. He laughed but did not say anything. He is willing to hear criticisms of his party and of his role. I once asked them whether it was a mistake for him to give the last Syrian security chief in Lebanon, Rustom Ghazali, an AK47 as a parting gift.

He thought about it for a minute and said maybe in hindsight it was. That is very rare among Lebanese and Arab leaders to do.

Please Donate Today to CN’s Fall Fund Drive

And when he, after 2006, said that had he known about the destruction and death of war maybe he wouldn’t have ordered the capture of Israeli soldiers to exchange them with Lebanese hostages. He was criticized for that by his Gulf-run enemies, as if he had said something wrong. In reality his statement exhibited concern for Lebanese lives.

Nasrallah, unlike most political leaders in Lebanon, was an excellent listener, and he listened to others and surrounded himself with advisers on different matters of interests.

There was never a Lebanese leader ever — and that includes all the leftists and communist leaders of the past — who invested more in the liberation of Palestine as he had. For him, it was a matter of doctrine that he inherited from Khomeini, for whom he had the utmost respect and reverence. (He once told me that only two people predicted the collapse of the Soviet Union: Zbigniew Brzezinski and Khomeini. I politely said that there were others).

His Mistakes

In tracking the political career of Nasrallah one has to acknowledge that there were many missteps and mistakes (from the point of view of his own interests) along the way.

First, there was the early period of Hezbollah when there were many acts of violence and kidnappings of innocent Westerners in Beirut. To that he said to me that this was prior to the period when there was an official Hezbollah organization.

Secondly, the entrance of Hezbollah into the political scene in the wake of the Hariri assassination was in my judgment a big political mistake because it allowed the party to steer away from its focus on fighting Israel and to get bogged down in the minute, dirty affairs of Lebanese politics.

Hezbollah, even with Nasrallah’s guidance, did not do well within the political system and its sectarian alliances, especially with the Tayyar Party of Michel Aoun, largely crumbled in recent years. I think he prioritized his alliance with the Shiite ally, Amal, over all other alliances, thereby depriving the party from much broader, multi-sectarian support in Lebanon.

That has proven to be a big mistake especially in light of the last year when the majority of Christian parties did not identify with the struggle of Hezbollah against Israel (and that is in contrast to the support that the Tayyar extended to Hezbollah in 2006).

Thirdly, Hezbollah’s intervention in Syria was another controversial matter that the party, which is dedicated to the struggle against Israel and imperialism, was sidetracked and got bogged down int in the civil war in Syria. One can understand that the decision (from its own perspective at least) to get involved in Syria, given the series of ISIS bombings and by other religious fanatics which targeted Shiites and Hezbollah, and given the relationship between some of those groups and Israel.

But the way Hezbollah managed that intervention enabled Hezbollah’s Arab enemies to paint it as sectarian. Much of the party’s rhetoric that accompanied that intervention was presented in sectarian terms, and not in terms related to the struggle against Israeli aggression and occupation.

The U.S. is celebrating the killing of Nasrallah and nothing will be said about the hundreds of innocent civilians who were crushed under the rubble after Israel dropped 85 devastating bombs over six residential buildings in the southern suburbs. Western media can refer to the incineration of all these residents of those buildings who turned into ashes as a “surgical strike.”

This is how NYT managed to justify the flattening of six residential buildings in Beirut: pic.twitter.com/xwugfkbELG

— asad abukhalil ???? ??? ???? (@asadabukhalil) September 30, 2024

The Israeli government admitted to having informed the Biden administration of the decision to kill Nasrallah, although the U.S. government tried unconvincingly to distance itself from that decision later.

But it is certain that the Biden administration must have approved the decision to kill Nasrallah after the U.S. government had turned down Israeli plans to kill him for many years.

More than 15 years ago I was giving a talk on the Arab-Israeli conflict at the University of Texas’ Law School. I recognized in the audience Admiral Bobby Inman (former deputy director of the C.I.A). During the Q and A, somebody asked me about Hezbollah and Nasrallah and whether Israel would take the decision to assassinate him.

I answered the question as best I could. Afterwards, Inman came up to me, introduced himself, and took me aside. He talked about that particular question, about the potential Israeli assassination of Nasrallah and said in blunt terms: Israel would not dare take Nasrallah out.

I said: why not?

He said: simple. Because the U.S. government told the Israelis categorically and repeatedly that they would not kill Nasrallah because of the repercussions for the region and U.S. interests.

Knowing that Biden has put no red lines on Israel since Oct. 7, he would be the one U.S. president who would also lift that one red line.

Nasrallah, unlike Nasser, leaves behind a doctrine and a strong organization that is likely to survive Israel’s unrelenting campaign of assassinations and slaughter. Hezbollah suffered a very severe blow, the worst since its formation, but it is likely to emerge again as a different organization under new leadership.

It is possible that U.S. opposed the assassination because it knew that no one but Nasrallah could control such a dangerous (from the U.S. point of view) organization.

After Nasrallah, the organization could become less disciplined and perhaps more dangerous to U.S. interests.

As`ad AbuKhalil is a Lebanese-American professor of political science at California State University, Stanislaus. He is the author of the Historical Dictionary of Lebanon (1998), Bin Laden, Islam and America’s New War on Terrorism (2002), The Battle for Saudi Arabia (2004) and ran the popular The Angry Arab blog. He tweets as @asadabukhalil

The views expressed are solely those of the author and may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Donate Today to CN’s Fall Fund Drive

The world does not yet know what a great man has been murdered by the most vile man.

Bombing residential buildings harks back to what happened to Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Dresden. It is mad by the standards of persons with hearts. It fits a forensic pattern, however.

According to polls about half the US population supports US’s unconditional support of the genocidal, Zionist regime in Israel.

What does it say about Americans? Or are the polls flawed?

They are heavily propagandised, so ‘half’ believe it, and the other half don’t.

As an American, I agree with the statement. I’m very much at odds with friends and family that support the Zionist genocide as well as our intervention in Ukraine. But, then again, I don’t get my information from main stream news sources and most everybody I know does pay homage to one of the several main stream sources. Some of them even taunt me and claim my sources are disinformation without even devoting one ounce of intellectual energy to read any of my sources.

In my opinion Mr. Mulcahy the polls cannot over come the influence of the AIPAC lobby.

No doubt many Christian Nationalists support the Mad Man in power now in Israel.

Unfortunately I missed the comment opportunity for Mr.Lawrence’s piece here “Nasrallah Is Dead . . .” . I say unfortunately because Mr. Lawrence displays a superior debt and sophistication of intellect. Much of what he has to say about Israeli mistakes in their current endeavors can be traced back to the teaching of Sun – tzu’s The Art Of War. Which if reviewed expose the fact the U.S. has fallen victim to whole sale bullying as opposed to conducting itself as a major military power, the same needs to be said about the Israelis.

I acquired a very good New Translation by Ralph D. Sawyer, copy ri9ht 1994, – Metro Books, from a great friend of mine. Patrick is definitely correct, in my opinion on his take on this debacle.

Thanks for another very informative piece!

Particularly crass and stupid, it seems to me, was Biden’s response immediately followed by Harris’s response, that Hassan’s death was “justice.” These people have wrapped themselves in a muddled personal history with no sense of empathy or perspective on an international crisis. Millions around the globe are not fooled by this type of self-righteous response. It is the behavior of sadists and maniacs. Moreover, not a word about how many in the exploded residential complex were sacrificed. EIGHTY 2,000 pound bombs were dropped on a residential area to get at a revered leader. Are they totally nuts, or what?

They simply have no morals or principles. Combine this with their overarching stupidity and self-satisfied ignorance, and then it’s no surprise why they do what they do.

Since when does ‘justice’ entail the slaughter of innocent civilians for it to be carried out? I’d like to hear the Biden/Harris response to this question.