The antidote to many of our mental health crises must come from re-building society and forming a culture of community rather than a culture of antagonism and toxicity.

Van Gogh – Starry Night. (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

In 1930, Clément Fraisse (1901–1980), a shepherd from France’s Lozère region, was confined in a nearby psychiatric hospital after he tried to burn down his parents’ farmhouse.

In 1930, Clément Fraisse (1901–1980), a shepherd from France’s Lozère region, was confined in a nearby psychiatric hospital after he tried to burn down his parents’ farmhouse.

For two years, he was held in a dark, narrow cell. Using a spoon, and later the handle of his chamber pot, Fraisse carved symmetrical images into the rough, wooden walls that surrounded him. Despite the inhumane conditions in these psychiatric hospitals, Fraisse made beautiful art in the darkness of his cell.

Not far from Lozère is the monastery of Saint Paul de Mausole in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where Vincent van Gogh had been confined four decades earlier (1889–1890) and where he completed around 150 paintings, including several important works, among them The Starry Night in 1889.

I was thinking about both Fraisse and Van Gogh when I visited the old Ospedale Psichiatrico Giudiziario (OPG) in Naples, Italy, in September for a festival that took place in this former criminal asylum, which once held those who had committed serious offences and were deemed to be insane.

The vast building, which sits in the heart of Naples on the Monte di Sant’Eframo, was first a monastery (1573–1859), then a military barrack for the Savoy regime during Italy’s unification in 1861, and then a prison set up by the fascist regime in the 1920s.

The prison was closed in 2008, and then, in 2015, occupied by a group of people who would later form the political organisation Potere al Popolo! (Power to the People!). They renamed the building Ex OPG – Je so’ pazzo; “ex” meaning that the building is no longer an asylum, and “Je so’ pazzo” referring to the favourite song of the beloved local singer Pino Daniele (1955–2015), who died around the time the building was occupied:

I’m crazy. I’m crazy.

The people are waiting for me.

….

I want to live at least one day as a lion.

Je so’pazzo, je so’ pazzo.

C’ho il popolo che mi aspetta.

….

Nella vita voglio vivere almeno un giorno da leone.

Today, the Ex OPG is home to legal and medical clinics, a gym, a theatre and a bar. It is a place of reflection, a people’s centre that is designed to build community and confront the loneliness and precarity of capitalism. It is a rare kind of institution in our world, one in which an exhausted society is increasingly isolated and individuals, encaged in a prison house of frustrated aspirations, nonetheless hope to use their meagre tools (a spoon, the handle of a chamber pot) to carve out their dreams and to reach for the starry sky.

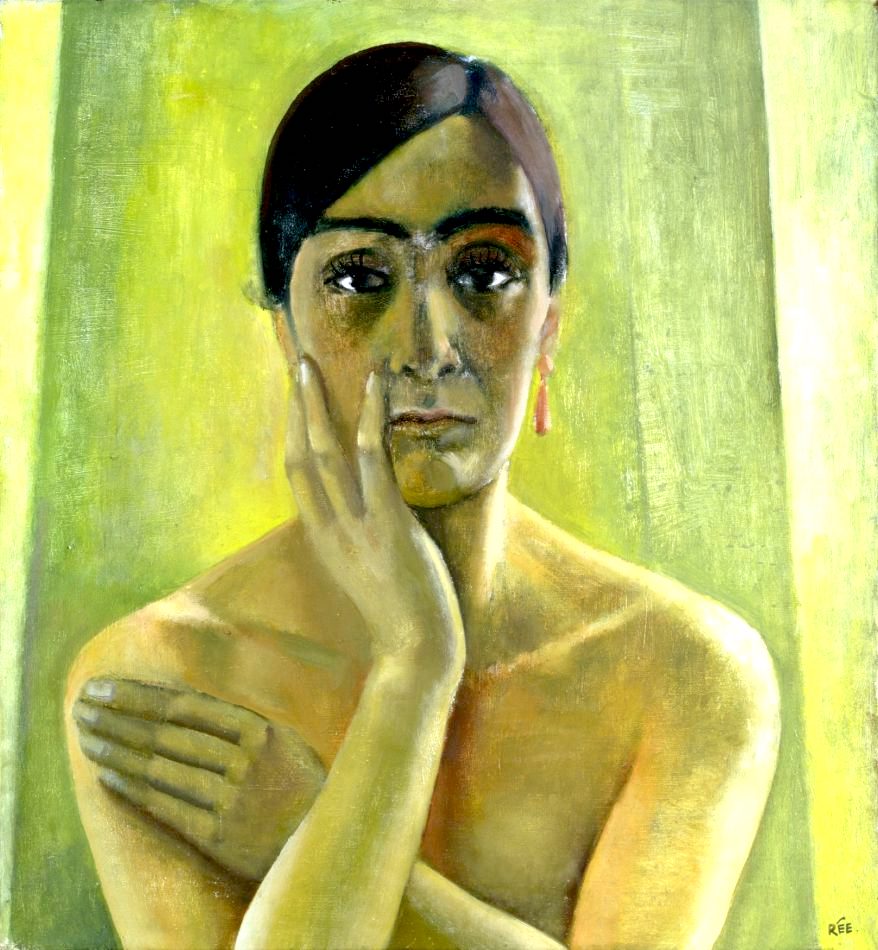

Anita Rée, Germany, “Self-Portrait,” 1930. Rée (1885–1933) killed herself after the Nazis declared her work “degenerate.” (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Even the World Health Organisation (WHO) does not have sufficient data on mental health, largely because the poorer nations are unable to maintain an accurate account of their populations’ immense psychological struggles. As a result, the focus is often limited to the more affluent countries, where such data is collected by governments and where there is greater access to psychiatric care and medications.

A recent survey of 31 countries (mostly in Europe and North America, but also including some poorer nations such as Brazil, India, and South Africa) shows a shifting attitude and increased concern about mental health.

The survey found that 45 percent of those polled selected mental health as “the biggest health problems facing people in [their] country today,” a significant increase from the previous poll, conducted in 2018, in which the figure was 27 percent. Third in the list of health challenges is stress, with 31 percent selecting it as the leading cause of concern.

Please Donate Today to CN’s

Fall Fund Drive

There is a significant gender gap in attitudes towards mental health amongst young people, with 55 percent of young women selecting it as one of their primary health concerns, compared to 37 percent of young men (reflecting the fact that women are disproportionately impacted by mental health issues).

While it is true that the Covid-19 pandemic heightened mental health problems across the world, this crisis predated the coronavirus. Information from the Global Health Data Exchange shows that in 2019 – before the pandemic – 1-in-8, or 970 million, people from around the world had a mental disorder, with 301 million struggling with anxiety and 280 million with depression. These numbers should be seen as an estimate, a minimum picture of the severe crisis of unhappiness and maladjustment to the current social order.

There are range of ailments that go under the name of “mental disorder,” from schizophrenia to forms of depression that can result in suicidal ideation. According to the WHO’s 2022 report, 1-in-200 adults struggle with schizophrenia, which on average results in a 10- to-20-year reduction in life expectancy.

Meanwhile, suicide, the leading cause of death amongst young people globally, is responsible for 1-in-every-100 deaths (bear in mind that only 1-in-every-20 attempts results in a death). We can make new tables, revise our calculations, and write longer reports, but none of this can assuage the profound social neglect that pervades our world.

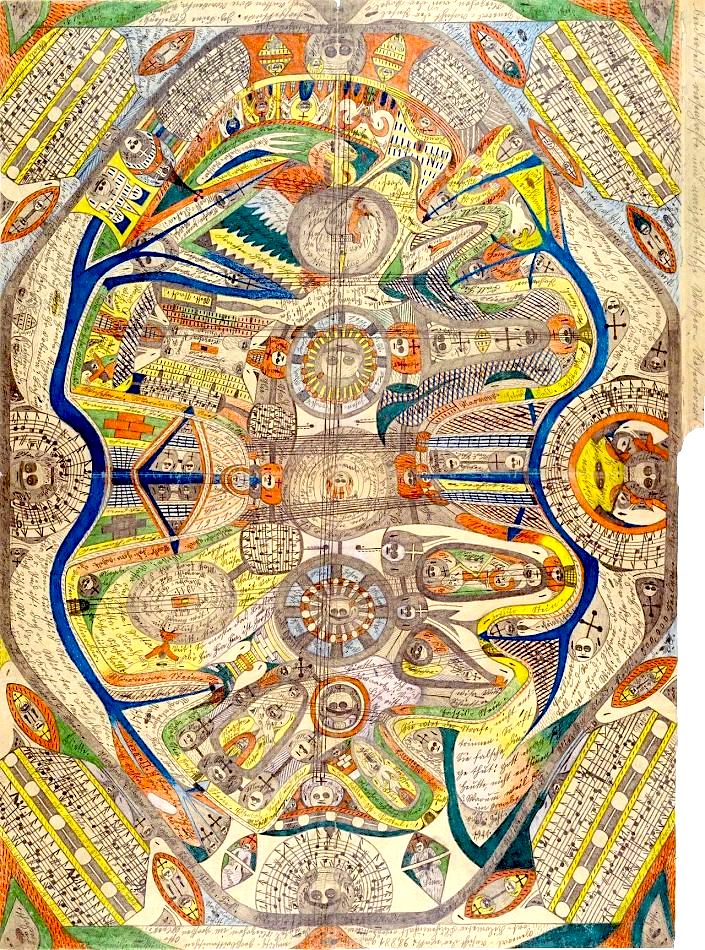

Adolf Wölfli, Switzerland, “General View of the Island Neveranger,” 1911. Wölfli (1864–1930) was abused as a child, sold as an indentured labourer and then interned in the Waldau Clinic in Bern, where he painted for the rest of his life. (Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Neglect is not even the correct word. The prevailing attitude to mental disorders is to treat them as biological problems that merely require individualised pharmaceutical care. Even if we were to accept this limited conceptual framework, it still requires governments to support the training of psychiatrists, make medications affordable and accessible for the population, and incorporate mental health treatment into the wider health care system.

However, in 2022, the WHO found that, on average, countries spend only 2 percent of their health care budgets on mental health. The organisation also found that half of the world’s population — mostly in the poorer nations — lives in circumstances where there is one psychiatrist to serve 200,000 or more people. This is the state of affairs as we witness a general decline of health care budgets and of public education about the need for a generous attitude toward mental health problems.

The most recent WHO data (December 2023), which covers the spike in pandemic-related health spending, shows that, in 2021, health care spending in most countries was less than five percent of Gross Domestic Product.

Meanwhile, in its 2024 report A World of Debt, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that almost a hundred countries spent more to service their debts than on healthcare. Though these are foreboding statistics, they do not get at the heart of the problem.

Over the course of the past century, the response to mental health disorders has been overwhelmingly individualised, with treatments ranging from various forms of therapy to the prescription of different medications.

Part of the failure to deal with the range of mental health crises – from depression to schizophrenia – has been the refusal to accept that these problems are not only influenced by biological factors but can be – and often are – created and exacerbated by social structures.

Dr. Joanna Moncrieff, one of the founders of the Critical Psychiatry Network, writes that “none of the situations we call mental disorders have been convincingly shown to arise from a biological disease,” or more precisely, “from a specific dysfunction of physiological or biochemical processes.” This is not to say that biology does not play a role, but simply that it is not the only factor that should shape our understanding of such disorders.

In his widely read classic The Sane Society (1955), Erich Fromm (1900–1980) built on the insights of Karl Marx to develop a precise reading of the psychological landscape in a capitalist system. His insights are worth re-considering (forgive Fromm’s use of the masculine use of the word “man” and of the pronoun “his” to refer to all of humanity):

“Whether or not the individual is healthy is primarily not an individual matter, but depends on the structure of his society. A healthy society furthers man’s capacity to love his fellow men, to work creatively, to develop his reason and objectivity, to have a sense of self which is based on the experience of his own productive powers. An unhealthy society is one which creates mutual hostility, distrust, which transforms man into an instrument of use and exploitation for others, which deprives him of a sense of self, except inasmuch as he submits to others or becomes an automaton. Society can have both functions; it can further man’s healthy development, and it can hinder it; in fact, most societies do both, and the question is only to what degree and in what directions their positive and negative influence is exercised.”

The antidote to many of our mental health crises must come from re-building society and forming a culture of community rather than a culture of antagonism and toxicity. Imagine if we built cities with more community centres, more places such as “Ex OPG – Je so’ pazzo” in Naples, more places for young people to gather and build social connections and their personalities and confidence. Imagine if we spent more of our resources to teach people to play music and to organise sports games, to read and write poetry, and to organise socially productive activities in our neighbourhoods.

These community centres could house medical clinics, youth programmes, social workers, and therapists. Imagine the festivals that such centres could produce, the music and joy, the dynamism of events such Red Books Day. Imagine the activities – the painting of murals, neighbourhood clean-ups, and planting of gardens — that could emerge as these centres incubate conversations about what kind of world people want to build. In fact, we do not need to imagine any of this: it is already with us in small gestures, whether in Naples or in Delhi, in Johannesburg or in Santiago.

“Depression is boring, I think,” wrote the poet Anne Sexton (1928–1974). “I would do better to make some soup and light up the cave.” So let’s make soup in a community centre, pick up guitars and drumsticks, and dance and dance and dance till that great feeling comes upon everyone to join in healing our broken humanity.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and, with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

This article is from People’s Dispatch and was produced by Globetrotter.

Views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Donate Today to CN’s Fall Fund Drive

‘It is no measure of health to be well adjusted to a profoundly sick society.’

Jiddu Krishnamurti

‘A sane person to an insane society must appear insane.’

Kurt Vonnegut Jr

‘The cost of sanity, in this society, is a certain level of alienation’

Terence McKenna

‘Now I understand

What you tried to say to me

And how you suffered for your sanity

And how you tried to set them free

They would not listen, they did not know how

Perhaps they’ll listen now’

Don Mclean

Xxxx://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2024/jan/21/hostile-architecture-is-making-our-cities-even-less-welcoming

Read this and weep and understand the state of the planet in the western hemisphere.

Thank you, Mr. Prashad for another superb offering. I walk away from your writing feeling very much as I do after reading anything by Chomsky. As a member of the anxious and maladjusted precariat, I take solace in your cogent and humane socio-cultural-historical aesthetic.

I’ve only just learned the meaning of precariat. It’s certainly a situation which could induce imagined and realistic frightening scenarios for the future. But these can be overcome. They are not a death sentence.

Every mammal, other than Homo sapiens, has behavioral as well as structural descriptions as part of its species definition. We evolved within and to environmental conditions that have become increasingly rare in individual experience; one of the aspects of the those conditions was the capacity to be effective and competent in meeting those challenges with one’s own skills, self-confidence and the power of close community ties. The impotence of the vast majority of people to more than make minor gestures of ‘power over their own lives’ can only result in the failure to organize a fully effective human animal within us…with all the varieties of ‘mal-adaptation’ so voluminously described in the DSM-5.

And a recognition for Don McLean, seemingly not here in the article.

Thank you Vijay for the important article, ‘When You Suffer For Your Sanity’. I have been the close observer of acute chronic mental health disorders, within my circle of family and friends, for many years. It has become obvious that the diagnosis of mental illness into essentially either schizophrenia or bi-polar disorder has been going on now for over 100 years without any resulting positive outcomes.

By this experience I have come to three conclusions:

All psychological distress arises from an unacknowledged abuse of one kind or another, not a mental ‘illness’ in the common sense.

The suppression of symptoms by use of psychotropic medication does not address this root cause.

These medications result in extremely dangerous mental and physical side effects that are debilitating in themselves.

If these medications are consumed over an extended period, such gross changes in brain function occur that it is impossible to ever entirely stop their use due to the cataclysmic withdrawal consequences. Vincent, Anita and Adolf would not have had the mental capacity to produce their art if they had been treated with these drugs.

This addictive chemical straight jacket, used by society to subdue those harmed by that very society’s toxic culture, will hopefully be realised in the future to be as primitive as lobotomy in C20th or permanent chained incarceration in the C19th.

The answer is highly skilled listening by a therapist able to instill the trust necessary for the damaged individual to verbalise the subconsciously repressed abuse they have experienced. From that newly conscious understanding sustainably meaningful lives and relationships are rebuilt and the symptoms of ‘mental illness’ vanish. This all takes time but avoids a lifetime of dependency upon the very expensive and debilitating drugs marketed as a false quick fix by Big Pharma.

I agree that we need to re-establish a sense of community, along with physical buildings that have meeting rooms, activity rooms, discussion groups, support groups, etc. These could be organized by the people in the community with the support of “professionals” who are community-focussed rather than “advice”-focussed. Professionals should be in the background and available, if needed, but not central if true community support and events are to occur.

Young people need to feel needed and respected. Seniors, as well.

This will all happen quite naturally if the attitude is one of compassion, support and respect.

Focussing on general well-being by working together to make sure everyone has adequate housing, clean water, healthy food, easy access to appropriate health care, including no more indiscriminate use of pesticides, herbicides and other toxic products.

That’s just the beginning of my “wish list” for a healthy society.