The historic English town of Jarrow has been a seat of working class rebellion for almost 200 years — and they’re not done yet.

Cameras: Cathy Vogan & Joe Lauria. Editor & Producer: Cathy Vogan

By Joe Lauria

in Jarrow, England

Special to Consortium News

From the mid-19th Century, the town of Jarrow, three miles from the North Sea coast in the county of Tyne and Wear, became one of the most rebellious working class towns in England — a defiance that continues until today.

Once one of the most important ship-building towns in the world with a thriving coal mining industry, Jarrow today is victim of the deindustrialization imposed on the north of England over the past four decades.

Margaret Thatcher unleashed the neoliberal economic policies that transferred wealth from the workers to the wealthy, policies of privatization, deregulation and shipping industrial jobs to cheap labor countries continued by her successors — Labour and Tory — devastating millions of lives.

The roots of rebellion in Jarrow go deep. Pitmen in the area in 1824 formed the first miners’ union in Britain — the United Colliers of Northumberland and Durham Association. They went on strike as early as 1832. Among the demands were reduced working hours for children from 16 to 12 hours.

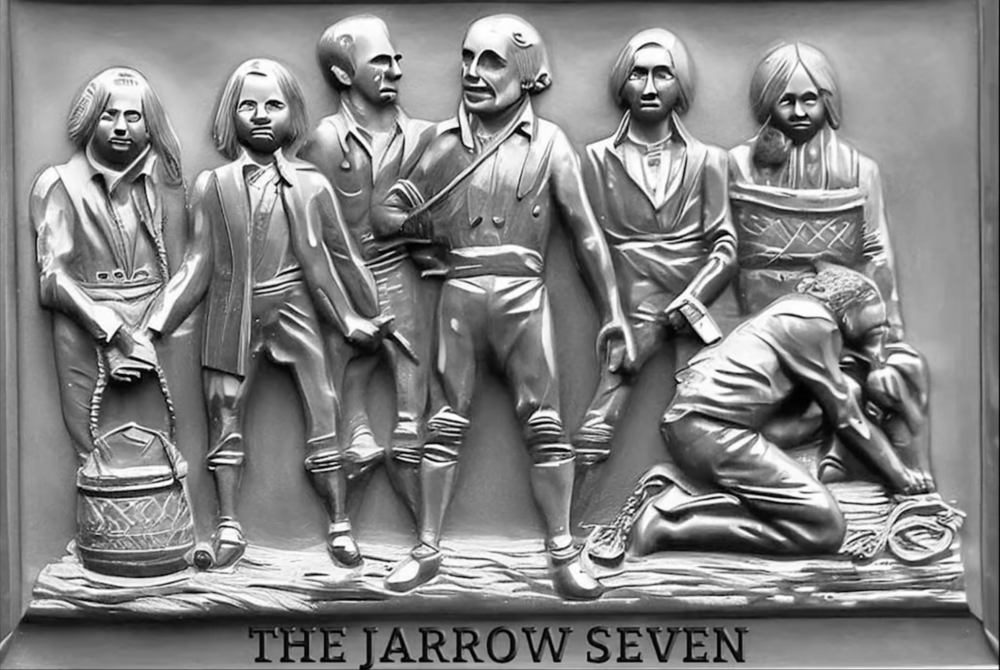

The Jarrow Seven

When two striking miners broke into a wealthy home to steal food and a pistol, ten miners were charged and convicted in a case of collective punishment. Three of the convicts escaped and the other seven were exiled from Jarrow — nine miles outside Newcastle upon Tyne — to Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia.

The Jarrow Seven were Thomas Armstrong, John Barker, Isaac Ecclestone, David Johnson, John Smith, Batholomew Stephenson and John Stewart.

The response to this injustice became violent. The local Shields Gazette reported:

“Violence escalated after the verdict. Strike breakers were attacked, a miner was shot dead, families evicted, strike meetings were attacked by armed police. …

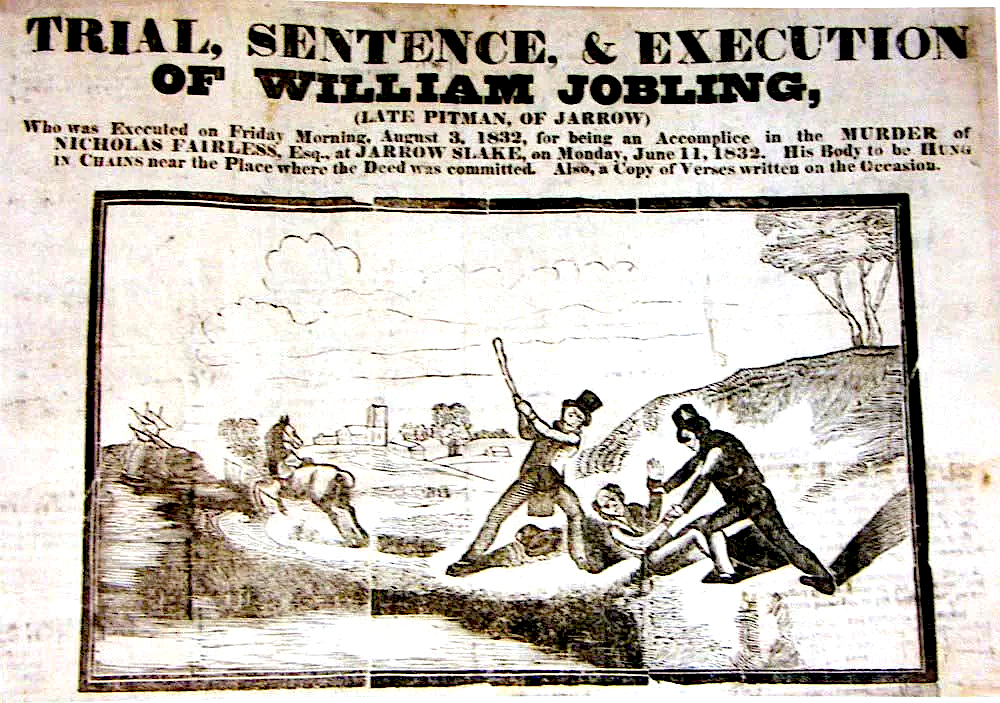

Following the killing of a magistrate, 71 year-old Nicholas Fairles, two men were arrested. One of them was Ralph Armstrong who was the brother of the deported Thomas Armstrong.

Ralph was identified by Fairles, who died 19 days after the attack. Armstrong’s companion, William Jobling, was arrested and tried, again under joint enterprise.

It was Armstrong who had struck the fatal blow to Fairles with a stick, but Jobling who was charged with murder.

Armstrong, clearly the more culpable of the pair, went on the run and was never seen again. Jobling was eventually sentenced at Durham to be hanged on August 3, 1832. The jury took 15 minutes to reach their verdict.”

An article in the publication UnHerd picks up the story:

“Jobling was hanged in 1832 and his body was tarred, hung in chains and bolted into a gibbet that was toured through the colliery districts to intimidate the striking pitmen. At Jarrow Slake it was then attached to a 21-foot wooden post to swing in the wind as a warning to all others (and in full view of the house where Jobling’s widow lived).”

Jobling was one of the last men so gibbeted in Britain. His body was ultimately cut down and left on the side of the River Tyne. It was brought to a pub by his friends and then secretly buried. A plaque marks the spot in town where the pub stood.

The Jarrow March

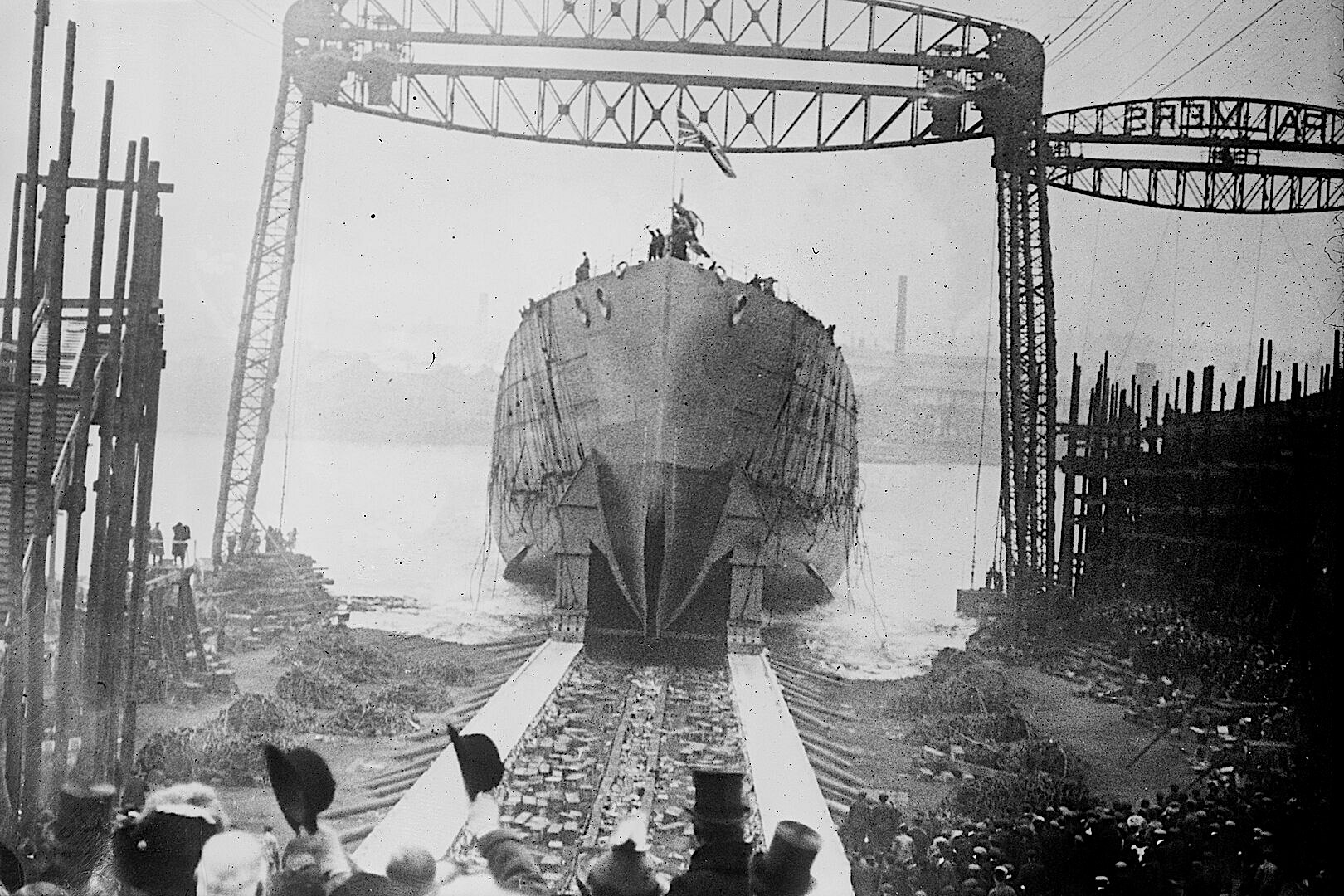

Launch of battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary at Palmer’s Shipbuilding, Jarrow-on-Tyne, England, March 1912. (Unknown, Baine News service/Library of Congress/Wikipedia)

Jarrow is best known in the annals of working class rebellion for the Jarrow March of 1936. Palmer’s shipyard in 1851 began constructing warships and supplying many of the world’s navies. It became the largest shipbuilding center in Britain and in the 1890s the U.K. made 80 percent of all ships in the world.

The company also employed 80 percent of the town’s workforce when it was forced to close in 1934 during the Great Depression, devastating nearly everyone who lived in Jarrow.

In July 1936, David Riley, chairman of Jarrow Borough Council, told a rally of the town’s unemployed:

“If I had my way I would organise the unemployed of the whole country … and march them on London so they would all arrive at the same time. The government would then be forced to listen, or turn the military on us.”

By Oct. 5, 200 unemployed “Crusaders” began their 280-mile march to Parliament. Supporters hosted them along the way each evening.

Two hundred and eighty-two miles and 26 days later, marchers arrived at Westminster on Oct. 31 with a petition signed by 12,000 Jarrow residents. It was presented to Parliament on Nov. 4.

It read:

“During the last 15 years Jarrow has passed through a period of industrial depression without parallel in the town’s history. Its shipyard is closed. Its steelworks have been denied the right to reopen. Where formerly 8,000 people, many of them skilled workers, were employed, only 100 men are now employed on a temporary scheme.

The town cannot be left derelict, and therefore your Petitioners humbly pray that His Majesty’s Government and this honourable House should realise the urgent need that work should be provided for the town without further delay.”

Besides a few remarks in Commons in support of the marchers, nothing happened. Essayist Ronald Blythe wrote at the time:

“And that was that. The result of three months’ excited preparation and one month’s march has led to a few minutes of flaccid argument during which the Government speakers had hardly mustered enough energy to roll to their feet.”

The crusaders took the train back to Jarrow where they were greeted as defiant heroes.

Jarrow Marchers en route to London, October 1936. (Collection of National Media Museum) (Photographer unknown)

A Deeper History

Just east of Jarrow the wall of Roman Emperor Hadrian begins, stretching across the north, built to keep the Picts and the Scots out.

In the Middle Ages, the Jarrow monastery was home of the Venerable Bede, the most important English clerical scholar, who wrote the Ecclesiastical History of the English People in 731 AD, making him the so-called Father of English History. He devised the AD dating system that starts with Christ’s birth.

The monastery was an important center of European learning, having had one of the world’s largest libraries at the time. The Jarrow Codex, the second oldest, single volume Latin Bible, was produced there and presented to Pope Gregory II in Rome in 716. In 794, the Anglo-Saxons repulsed a Viking raid at Jarrow.

Washington

Just 15 miles away is the town of Washington, D.C. T.W., that is, Washington, Tyne and Wear, the family home of that great American rebel, and English traitor, George Washington. His ancestors’ house, Washington Old Hall, is now run by the National Trust.

It incorporates part of a medieval manor owned by Washington’s ancestors from the mid-13th century. In 1977, Jimmy Carter became the only U.S. president to have visited Washington Old Hall.

Remembering That History

Today Jarrow, with its shipbuilding and coal mining past, is part of the great Northern economic devastation, which is at the root of the region’s unrest earlier this month.

There were race riots in Jarrow in 1937, but the town has experienced no riots this summer. Jarrow’s population is 96.8 percent white, and there are only 365 Muslims living in a town of nearly 30,000 inhabitants.

But Jarrow suffers from the deindustrialization that is at the heart of the Northern unrest, fueling Jarrow’s memories of its rebellious history. It is commemorated every year in June with new calls for resistance. The article in UnHerd said:

“Just in recent weeks it’s been reported that the North East has not only the highest levels of child poverty, and the greatest number of deaths from opioid abuse, but it has also seen the sharpest fall in life expectancy of any English region. So, I find it hard to shake the pessimistic view that the North, having experienced a relatively brief few centuries of industrial prosperity, will never again throw off its subordination to the South, or indeed the legacy of its century-long economic decline.”

This year, on the 40th anniversary of the British miners’ strike, Arthur Scargill, the now 86-year old union leader from that 1984 action spoke in Jarrow.

On this Labor Day in the United States, watch the above video by CN Live!’s producer Cathy Vogan to see the spirit of working class rebellion alive and well in the north of England.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former U.N. correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, and other newspapers, including The Montreal Gazette, the London Daily Mail and The Star of Johannesburg. He was an investigative reporter for the Sunday Times of London, a financial reporter for Bloomberg News and began his professional work as a 19-year old stringer for The New York Times. He is the author of two books, A Political Odyssey, with Sen. Mike Gravel, foreword by Daniel Ellsberg; and How I Lost By Hillary Clinton, foreword by Julian Assange. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe

What’s really needed for the British working classes now the old Labour Party has been captured by neoliberals is a new political party representing the left-of-centre. Some say left and right don’t exist anymore, but as there will always be people who must work for a living and there will always be businesses which must employ others to make a living, there will always be left and right in politics.

It’s hard for some outside the UK to grasp what a class-ridden society Britain has been since 1066 when the Normans conquered us. It’s more like a caste system, and today’s British aristocrats probably have closer genetic links to pre-1066 France than they will ever have to the British working and middle classes. We are that different, and their neoliberalism will take us back to feudalism if we cannot stop it. Maybe that’s what it’s meant to do.

I read a book about neo-Catholicism which outlined the very clear plans by powerful men to return us to feudalism. Check out the Knights of Malta, for example, one being Leonard Leo who owns Sen Susan Collins and told her who to put up for the Supreme Court. You got it: Gorsuch, Kavanaugh, Barrett. I’m not interested in individual players as much as I am learning about their clubs, societies, etc, where they plan out our lives for us.

I agree with your description of the working-class and the “aristocrats” of British Society, Michael. Wouldn’t you say it became worse under the fascist union-busting Margaret Thatcher and ever since?

Here in the States, the progressive movement gained much after WWII, but started going downhill when Raygun Reagan got away with firing the Air Traffic Controllers during the PATCO strike, and still worse for unionized labor in the transportation industry when Jimmy Carter and Ted Kennedy deregulated those industries, all within the first two years of the 1980’s.

The super-rich want to turn the clock back to the days of master and serf feudalism as the greed for more money and power for and by them is insatiable. But, that’s capitalism for ya!

“… to see the spirit of working class rebellion alive and well in the north of England.”

And don’t forget the annual Durham Miners Gala

hxxps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z4XNONAwf94

Strong and uplifting. It is very good to hear the people, speaking from the heart.

Thank you.

From the haunting song with banjo by Tony Wilson: “We are many, they are few.”

To quote the late-lamented and MURDERED Andre Vltchek:

“Nothing will change until people are willing to die for it.”

When he went to Greece in 2009, he found no one willing to die fighting the devastation and found that most Greek people had little interest in the suffering in Africa. He said, “Don’t advocate for national health care, advocate for universal health care!”

Dear Susan, I liked your comment, having read his columns for years and meeting Andre Vlitchek in person at a lecture years ago, was a genuine humanitarian, and to me, a Christ-like man whom I wonder to this day if he was murdered by the Deep State for speaking “Truth To Power.”

Much too young to die mysteriously. As you know, Andre lived in many parts of the world and reported on so many things, especially about Russia and China, which I’m sure upset the human rodents running the New World Order for total control of everything.

And thanks to Joe Lauria for another fact-filled history Lesson on the courageous people of Jarrow, England and their plight today.

My thoughts on this article: WORKERS of the WORLD, UNITE, and STAND TOGETHER, as there are more of us then them – the Oligarchs who control the politicians with money for their own selfish and insatiable interests. National and Worldwide General Strikes are long due until our needs and conditions are met. For sure!

I agree totally with you, Frank, but insidious neoliberalism has become so much a part of Western “consciousness,” that I fear people’s ability to work together has been destroyed. I saw this in the 1960s and 1970s in antiwar groups, feminist groups, socialist groups. A group of socialists had a gathering in Boston and then complained about no working-class people attending. As I was working-class I found this quite funny, and unfortunately quite telling because I was regularly patronized by “left-wing” activists who thought themselves superior. I’ve come to believe that this is a significant facet of college “education,” and the first thing people must do is rid themselves of such silly notions which divide people.

Regarding Vltchek — wish I had heard him speak! — originally Turkey said they were going to do an autopsy, but they must have been seriously pressured. Did you ever hear what Andre said about his more recent experiences speaking to college audiences in the US? Basically he said they were a bunch of zombies, didn’t even appear to be alive.

You have a good head for intelligent reasoning and discernment, Susan! You are (unfortunately) totally correct about the faux liberals in this country who opposed Bush Jr’s “wars of aggression, the signing of the un-Constitutional Patriot Act which was probably written before 9-11, but once the neoliberal compulsive liar, Obama became POTUS, the demonstrations ad anti-war marches literally ceased because he had a “D” after his name instead of an “R,” and I was called a racist for pointing it out. I proudly voted for the Honorable Cynthia McKinney for President, but in their minds, it didn’t count. Same thing with organized labor. They thought once the DemoRATS had the majority in the U.S. Senate, the House, and the White House, which they initially did, EFCA (Employee Free Choice Act) and Single Payer (Medicare for All) would be implemented but they were “taken off the table by Pelosi, Harry Reid, and Obama soon after he took office. But yes, you’re correct on the so-called college left-wing activists, to this day, still aligning themselves with the DemoRATS who love war, Wall Street and Israel as opposed to those “right-wing” Repulsive party politicians and members who love war, Wall Street and Israel. Money makes strange bedfellows, doesn’t it? Yes, Susan, divide and conquer is the name of the game.

If I recall correctly Vlitchek did mention in one of his articles about some of the US college audiences in what you described above and he may have been disillusioned by their tepid response and answers. May he rest in Peace.

On neoliberalism, if you want to read a real bombshell of a book, get a copy of: “the SCOURAGE of NEOLIBERALISM” subtitled: US Economic Policy From Reagan To Trump” by Dr. Jack Rasmus (jackrasmus.com)You can read his articles on his website and hear his podcasts too!

Good hearing from you Ms Siens.