In Brazil’s Rio Grande do Sul, millions are suffering from extreme flooding. Amid the waters, the Landless Workers’ Movement is focused on providing emergency relief.

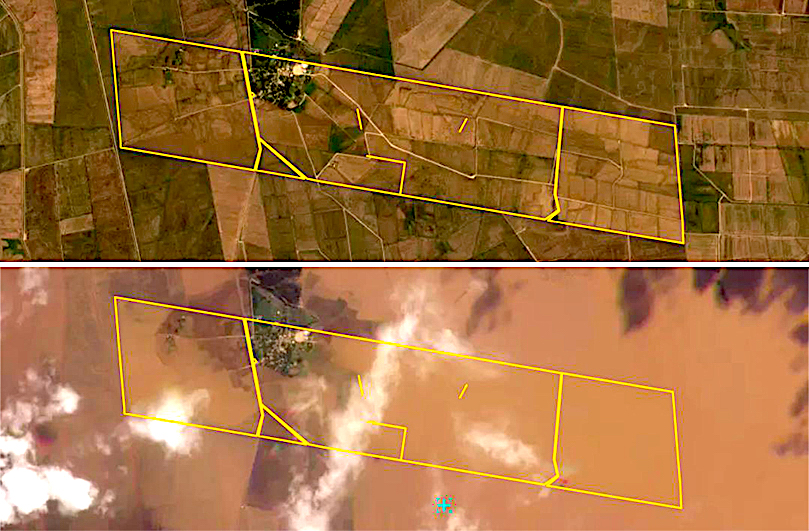

Padre Josimo Settlement. (Brazil M.A.I.S. Programme, Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

By Vijay Prashad

Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research

Heavy rains, strong winds and widespread flooding have lashed the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul since the end of April, killing over 160 people and impacting 2.3 million.

Heavy rains, strong winds and widespread flooding have lashed the southern Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul since the end of April, killing over 160 people and impacting 2.3 million.

The waters rose and rose again, rushing through houses and fields, erasing not only homes and the memories built there but also many crops in the country’s largest rice-producing state and agricultural powerhouse, the impacts of which are likely to reverberate across the nation.

Meteorological agencies and officials predicted the events with eerie precision. A week into the flood, experts pointed to the extraordinary rainfall as the primary cause.

Estael Sias, managing director of the weather forecaster MetSul, wrote that this was not “just an episode of extreme rain,” but “a meteorological event whose adjectives are all superlative, from extraordinary to exceptional.”

The seemingly unending rain, she wrote, “is absurdly and bizarrely different from what is normal.” It will take a very long time for this region of Brazil to recover from the flood.

Within the floodwaters are several encampments and settlements of Brazil’s Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), about which we published a dossier last month to commemorate the movement’s 40th anniversary.

The MST was born from land struggles in Rio Grande do Sul, where it retains a strong presence and has become the epicentre of the MST’s agroecological rice production. These are the same fields on which the MST grew much of the 13 tonnes of food that it donated to the Gaza Strip from October to December of last year and the more than 6,000 tonnes of food that it donated to communities in need during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many of these fields, as well as the facilities used to process their harvests, have been damaged by the flood. Residents of MST settlements such as Apolônio de Carvalho and Integração Gaúcha Settlement have lost immense amounts of their resources.

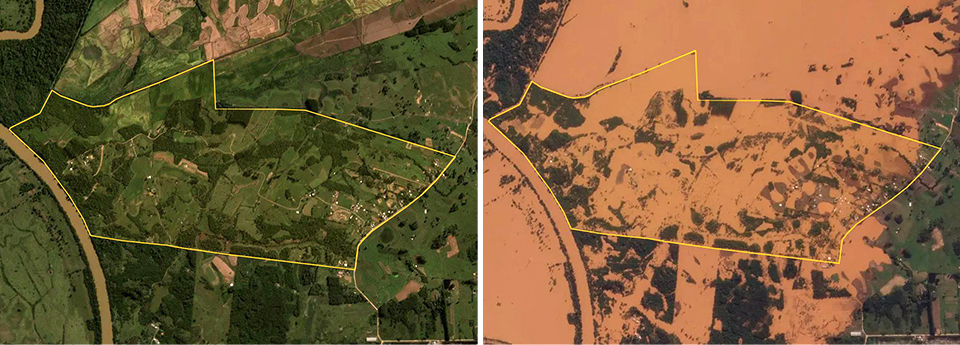

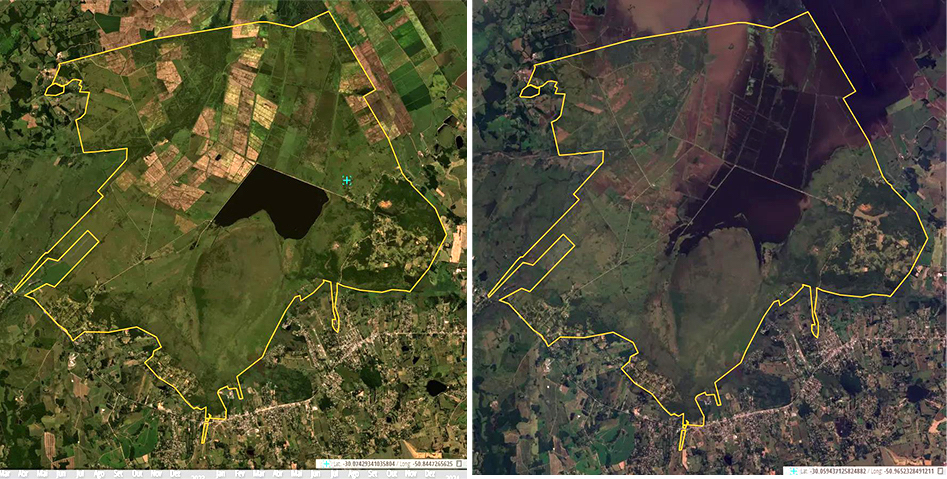

The images in this article, taken from a report by Brazil’s National Institute of Colonisation and Agrarian Reform (INCRA) using satellite images from the Brazil M.A.I.S. Programme, Ministry of Justice and Public Safety, show some of the MST’s lands before and after the floods — lands now inundated with flood water that has washed toxic materials into the soil.

The MST has focused its relief efforts not only on its own members, but also on the people of the region who have lost everything in the face of rising waters from which they cannot escape. If you wish to assist the MST in its flood relief efforts and to rebuild the settlements, you can do so here.

Santa Maria Settlement. (Brazil M.A.I.S. Programme, Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

Last year, after a much less serious flood impacted Porto Alegre (the capital of Rio Grande do Sul), the Brazilian architect Mima Feltrin, drawing from the work of hydrology professor Carlos Tucci, warned that the state faced an imminent risk of flooding equal to or worse than the historic floods of 1941 and 1967.

The analyses of scholars such as Tucci and Feltrin have repeatedly warned about the impact and looming threats of carbon emissions-driven climate change across the world as well as the deficiencies of policies put in place by reckless climate change denialist politicians.

As floodwaters rose in Rio Grande do Sul in 2023, so too did they inundate Derna in Libya, central Greece, southern China, southern Nevada in the U.S., and northeastern Turkey. The immediate explanation for these floods is that they are caused by carbon emissions-driven climate change, intensified by the refusal of Global North governments to contain their outsized carbon emissions.

But the broader explanation is that the climate catastrophe is largely the product of reckless capitalist development, particularly in cities located within areas that are predictably dangerous to inhabit (such as lowland coastal settlements built next to savaged mangrove forests and badly managed river flow or beside forests that face long periods of dry weather).

This reckless development is exacerbated by the rampant underfunding of environmental regulatory agencies and the deliberate slashing of budgets that maintain and revitalise infrastructure that is crucial to protect people from adverse climate events.

With the flood in Libya, for instance, the state — already destroyed by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s harsh bombardment in 2011 and pickled in confusion and corruption — neglected the crumbling dams of Derna. Much the same kind of attitude has been on display in southern Brazil for the past several decades.

Santa Maria Settlement. (Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

The two most recent mayors of Porto Alegre, Nelson Marchezan Júnior (2017–2021) and Sebastião Melo (2021–present), as well as the governor of Rio Grande do Sul Eduardo Leite (2019–March 2022 and then January 2023–present) spent their tenures eroding the basic institutions of their administrations.

Gov. Leite, for instance, undermined 480 rules of his state’s environmental code as part of the anti-environmental agenda pursued by the far-right President Jair Bolsonaro (2019–2022).

Meanwhile, Mayor Marchezan Júnior ignored the need to fund flood prevention infrastructure, including the renovation of thirteen pump houses that were central to Porto Alegre’s drainage system, and his administration shut down the entire Department of Storm Drainage Systems (DEP), which had been set up in 1973 to manage drainage.

Marchezan Júnior and Melo, along with their predecessor José Fortunati, each cut the number of employees in the departments that managed sewage and water systems.

People such as Leite, Marchezan Júnior and Melo hold an attitude of disregard for the majority of the population and an attitude of the highest regard for the offshore bank accounts of the wealthy and their friends, the Western investor class.

These people have been shaped by Brazilian big business, whose interests are consolidated by groups such as Instituto Liberal, set up in 1983 to further the neoliberal ideas of Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises; and by intellectuals of the military dictatorship (1964–1985) such as its economic ministers Roberto Campos and Hélio Beltrão.

These ideas were brought into the mainstream by Brazil’s former President Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1995–2003), whose Plan for the Reform of the State Apparatus (1995) used the idea of “modernisation” to undermine state institutions and to start what Professor Elaine Rossetti Behring called a period of “permanent fiscal adjustment.”

Cardoso, Leite, Marchezan Júnior and Melo are Men of Austerity, proponents of a counter-revolution against humanity.

Filhos de Sepé Settlement. (Brazil M.A.I.S. Programme, Via Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research)

When the catastrophe comes, as it has in Rio Grande do Sul, these neoliberal officials are quick to blame climate change, as if it were some sort of inevitability in which they played no part. However, when it comes to the climate, these people are the first to advance the agenda of fossil fuel companies and promote ideas and policies that amount to climate change denialism.

Their denialism is not rooted in science, but in class interests that prioritise big business over people and the planet. They do not have any scientific arguments to explain the climate catastrophe, since there is no scientific basis for denialism, which seeks — with complete disregard for the fate of the planet — to ensure the upward distribution of wealth.

From 1968 to 1980, the Brazilian poet Mário Quintana (1906–1994) lived in the Majestic Hotel in Porto Alegre, where he wrote beautiful poems of what he called “simple things.”

Shortly before Quintana died, his supporters and friends built the Casa de Cultura Mário Quintana in the Majestic Hotel, which the state government purchased, restored and transformed into a cultural centre in the 1980s. This hotel, Quintana’s home, became a haven for writers and artists to show their work. It was inundated by this year’s flood.

In 1976, from that hotel, Quintana wrote “A Grande Enchente” or “The Great Flood”, motivated by the floods of 1941 and 1967:

Cadavers of Ophelias and dead dogs

stopped momentarily at our doors,

though, ever at the mercy of the maelstrom,

they will continue along their uncertain path.

When the water reaches the highest windows

I will paint roses of fire on our yellow faces.

What does it matter what is to come?

The mad are spared all

and allow themselves everything.

Let us embark, spirit of the Gods.

Over the waters we glide.

Some say that we are merely clouds.

Others, the few, say that we are increasingly dying,

but I cannot see, down below, our dead.

And in vain I look around.

Where are you, friends,

from the very first and last days?

We must, we must, we must continue together.

And so, in one last, diluted thought,

I feel that my cry is but the gasp of the wind.

Vijay Prashad is an Indian historian, editor and journalist. He is a writing fellow and chief correspondent at Globetrotter. He is an editor of LeftWord Books and the director of Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research. He is a senior non-resident fellow at Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China. He has written more than 20 books, including The Darker Nations and The Poorer Nations. His latest books are Struggle Makes Us Human: Learning from Movements for Socialism and, with Noam Chomsky, The Withdrawal: Iraq, Libya, Afghanistan and the Fragility of U.S. Power.

This article is from Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.

Views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Please Donate to the

Spring Fund Drive!

“The mad are spared all

and allow themselves everything.”

The mad are running the world and care nothing for anything but themselves…

With the realities of climate change, all governments should be building new flood control measures to match the new reality. Humanity knows how to do this. These days, we have computer models that can predict what magnitudes of rains will occur. Every story about such an event includes the phrases of the predictions. Humanity knows how to build flood control structures for a given amount of rain. None of that is new. Tell any competent civil engineer what rainfall to design for, and they can produce a plan of what is required. Humanity has been doing this for centuries, probably longer if I knew Chinese history.

The problem is that the rich refuse to spend the money to do so. They know their mansion on the hill won’t be flooded, and they can always helicopter in more champagne and caviar. Or perhaps just decamp to their apartment in Monaco for a while, where they can tell their rich friends on the beach about how there was “soooooooo much rain”. This happens because the rich don’t care.