After spreading communal terror and stoking vicious sectarian violence, Britain’s man in Northern Ireland leaves a dark legacy hanging over the West, writes Mick Hall. Second of a two-part article.

Read Part One: A Blueprint for Counter-Insurgency in the West

By Mick Hall

Special to Consortium News

In a long obituary by the U.K. establishment broadsheet The Daily Telegraph on Jan. 4, General Sir Frank Kitson’s time in Northern Ireland is summarised in one paragraph:

In a long obituary by the U.K. establishment broadsheet The Daily Telegraph on Jan. 4, General Sir Frank Kitson’s time in Northern Ireland is summarised in one paragraph:

“Promoted to brigadier, he took command of 39th Air Portable Infantry Brigade in Belfast in 1970. He took a firm grip on the divided city, taking down the barricades and sending his men into the former ‘no-go’ areas. He was appointed CBE for gallantry. In retirement, he gave evidence to the Saville Inquiry into Bloody Sunday.”

The summary whitewashes the nature of this “firm grip.” In 1971, the Parachute Regiment entered the Ballymurphy housing estate in west Belfast, an IRA urban stronghold, looking for activists to round up as part of Operation Demetrius (internment without trial). They shot dead 10 civilians.

A year later the same regiment, known within military circles at the time as “Kitson’s private army” killed 14 unarmed civilians taking part in a civil rights march in “free” Derry, another “no-go” area for civil authorities. The incident became known as Bloody Sunday.

Terror became a tactic not only in the streets, but also in military holding centres. In August 1971, 14 men were taken from Long Kesh internment camp to a secret torture centre near Ballykelly in Derry and subjected to the “five techniques” for nine days straight.

They were hooded, made to stand in a prolonged stress position against the wall, subjected to a “white noise,” while deprived of sleep, food and drink. They were also thrown out of helicopters after being told they were above the Irish Sea, only to fall several feet to the ground. The men were never the same afterwards, suffering mental and physical health afflictions.

The lauding of 'war criminal' General Sir Frank Kitson is appalling, says Eamonn McCann: "The British establishment have learnt no lessons from their colonial experiences. In the Bogside, Kitson is remembered with revulsion."https://t.co/w6J1hTAFxB

— Suzanne Breen (@SuzyJourno) January 4, 2024

In a case brought by the Republic of Ireland, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in 1978 found use of the techniques “inhumane and degrading treatment.”

In June last year, the Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) apologised to the “Hooded Men” for not pursuing charges against the military at the time. It followed a U.K. Supreme Court ruling in 2021 that the techniques should have been characterised as torture.

There is evidence the techniques were used elsewhere. In 2003, Iraqi Baha Mousa died after interrogation by British soldiers. At an inquiry into his death in 2009 it was revealed he was subject to the same treatment as the Hooded Men.

In June 2023, Francesca Albanese, the U.N.’s special rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967, delivered a report to the Human Rights Council. It contained a description of Israeli treatment of Palestinian detainees that could be considered remarkably similar to the five techniques:

“being hooded and blindfolded, forced to stand for long hours, tied to a chair in painful positions, deprived of sleep and food, or exposed to loud music for long hours; and being punished with solitary confinement.”

Communal Terror

Christopher Stanley, Kevin Winters’ associate, believes the techniques were a way to induce terror among the Irish Catholic population in Northern Ireland.

“The deliberate use of the five techniques wasn’t for intelligence gathering, it was to send a message back to communities,” he says, adding that the same was true for the Ballymurphy housing estate in west Belfast.

“There were no IRA men in the Ballymurphy estate, they’d all pissed off down south of the border. So, there is that sort of collective retribution and sending messages out to communities.”

Ciarán MacAirt, manager of the state victims’ charity Paper Trail, agrees the Ballymurphy massacre was an act of repression on a civilian population on state orders and that suggestions it was the result of undisciplined soldiers was a fiction.

He says archival evidence shows paratroopers involved were reporting upwards and that these reports differed from what the army told the media at the time. The army said they had come under fire and those killed were IRA activists. At a subsequent coroner’s inquest decades later, army lawyers said the soldiers perceived a threat and soldiers acted without discipline.

“The full weight of the state was wheeled in behind their murders to protect them,” MacAirt says.

“Are we to believe that the Parachute Regiment — arguably one of the best trained and most disciplined regiments in the British Army — had a number of separate units under little command and control roving an estate in west Belfast, and that each targeted and executed unarmed civilians?”

The 35th Bloody Sunday memorial march in Derry, Jan. 28, 2007. (kitestramuort, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 2.0)

There is evidence of collective punishment carried out by other army regiments in Belfast during the early 1970s, a pattern of civilian killings in response to soldiers’ deaths at the hands of the IRA, he adds.

“In 1972, seven soldiers of the King’s Regiment were killed and scores injured in the Springhill/Whiterock area of west Belfast. That is obviously devastating for their loved ones. It is also true that this regiment left a trail of devastation in its wake as they killed civilians after their soldiers were killed and injured. The victims of the King’s Regiment included young school girls, teenagers and the local priest.”

Kitson’s Enemy

Kitson faced an implacable enemy in the IRA, a modern structural response to colonialism in Ireland that can be traced back several centuries.

The organisation had faded into obscurity after the failure of its 1950s border campaign, but came back with a vengeance after a civil-rights movement in the late 1960s, inspired by African-Americans, was violently suppressed by Northern Ireland’s regime based at Stormont.

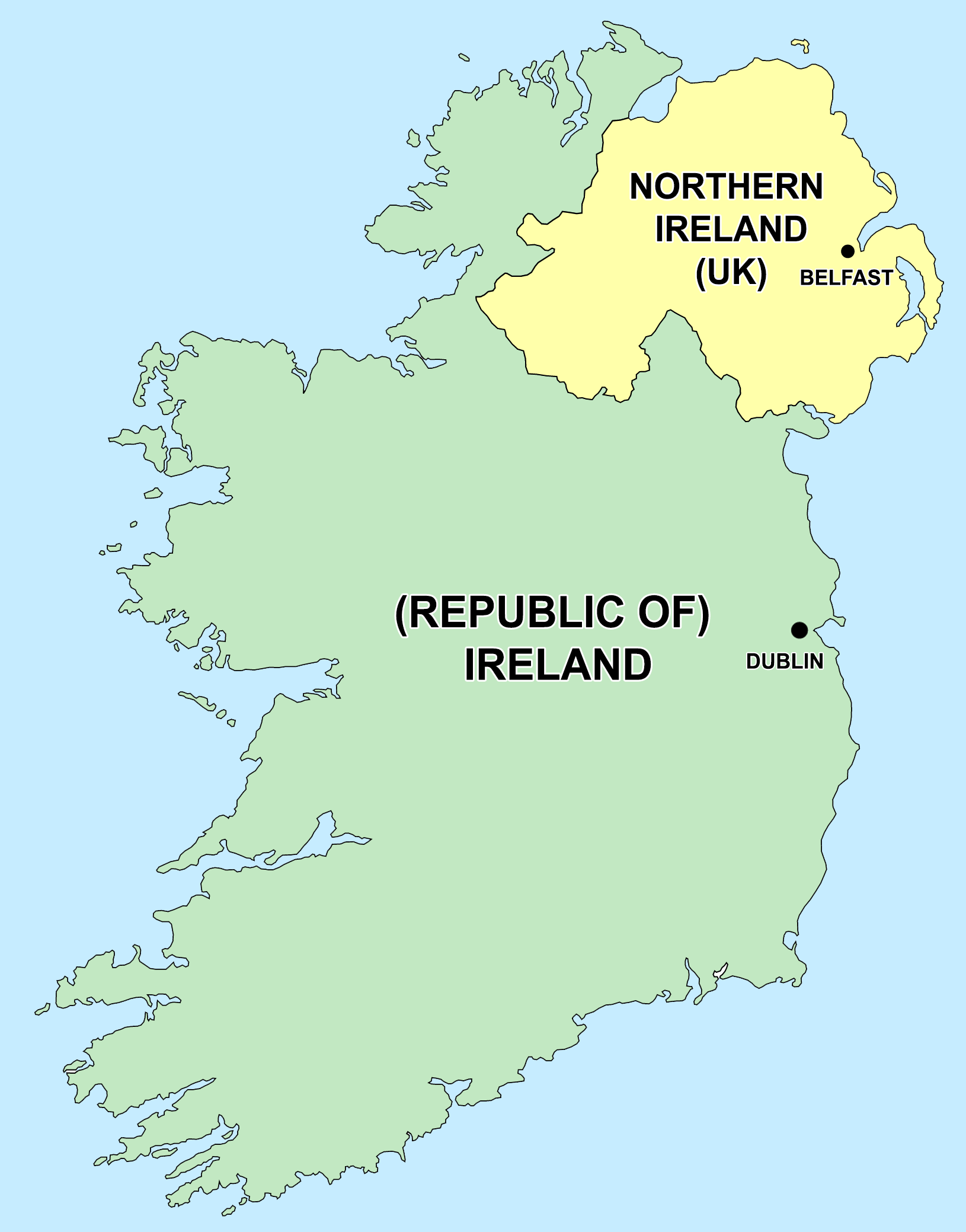

Irish Catholics trapped in the northern statelet under Britain’s jurisdiction following the island’s war of independence and its subsequent partition in 1921, had faced systemic economic and social inequality, periodic pogroms and a gerrymandered electoral system that kept them in a state of perpetual powerlessness.

Map of Ireland and Northern Ireland. (Kajasudhakarababu, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Northern Ireland had been created with an inbuilt majority of “unionist” Protestants, descendants of the original colonial “planters” of the 1600s, guaranteeing a sectarian status quo as part of Britain.

It was, in the words of its first prime minister, Edward Carson, “a Protestant state for a Protestant people.”

Threatened by a more assertive Irish Catholic population, sectarian mobs accompanied by the state’s paramilitary police and local militia displaced thousands of Irish Catholics during Belfast pogroms in 1969. Finding itself unable to defend the Irish Catholic population under siege, the IRA split, with the more militant “Provisional” IRA faction coming to the fore as the defenders of beleaguered communities.

It wasn’t long before defence turned to offense. The suppression of the non-violent civil rights movement and the British Army’s arrival in 1969 to reimpose “law and order” created rage and the objective conditions for a renewed armed struggle to end British rule in Ireland.

Bloody Sunday

Bloody Sunday in particular acted as an effective recruiting sergeant for the IRA, with young Irish Catholic men and women joining in their droves.

Seamus McKearney was among them and he immediately came up against Kitson’s counter-gangs.

In 1972, McKearney was just 16 when he ventured out on his first IRA operation on the Glen Road in west Belfast.

A bright orange car slowed to a crawl in front of him and another activist. The back window was down and by the time Kearney saw the barrel of a weapon pointing out, the car was just metres away before they started to run.

“As the car slowed, I could see a man at the back with black greasy hair and a moustache aiming the submachine gun. I remember the yellow flame as he began firing, about 20 rounds at me and the person I was with,” he says.

It was McKearney’s baptism of fire. He was hit but escaped serious injury, unlike his associate, who was smuggled south across the Irish border to receive life-saving medical treatment.

McKearney went on to become an IRA commander in Belfast, an experienced gunman who would also take part in the IRA Maze Prison protest against Britain’s policy of removing the political status of inmates, a strategy aimed at criminalizing his movement. The “blanket” protest culminated in the deaths of 10 Irish hunger strikers in 1981 under the leadership of Bobby Sands.

Bobby Sands mural in Belfast. (William Murphy, Flickr, CC BY-SA 2.0)

At the time of his shooting, McKearney believed it was a random sectarian attack by loyalist paramilitaries. It wasn’t until a military lecture given by revered IRA leader Brendan “The Dark” Hughes at the Maze Prison in 1985 that he realised it was the work of one of Kitson’s covert military units and began to fully understand the rationale behind many of their attacks.

“The Dark presented a talk on Kitson and counter-insurgency and the methods the British used,” McKearney says.

“He described how the MRF had operated, carrying around seized IRA weaponry like Thompson submachine guns, firing from cars… He asked if anyone had experienced that and I thought ‘that happened to me.’ ”

McKearney says he identified the gunman as Sergeant Clive Williams, after seeing a photo of him in the media years later when the soldier received a medal for bravery in service to the Crown.

Unbeknown to McKearney at the time, in 1973 Williams stood trial and was acquitted at Belfast Crown Court for attempted murder of four civilians shot just weeks after McKearney was shot at and near the same spot.

A BBC TV Panorama investigation in December 2013 found the Military Reaction Force carried out many such “drive-by” shootings of ordinary Irish Catholics. Kitson’s gangs weren’t just targeting IRA activists.

McKearney says Hughes’ lecture also focused on how Kitson’s targeting of Catholic civilians had attempted to trigger tit-for-tat reprisals from the IRA, to distract the group from engaging with the security forces and instead drawn them into a vicious sectarian conflict.

“They were trying to spark retaliation and drag us into a sectarian war,” McKearney says. “The only people who would have benefited was the British… who could also better portray the conflict as one where they’re stuck in the middle of two warring tribes.”

McKearney lists three bomb attacks on bars in west Belfast that killed several people during 1976 as examples of such provocations. The IRA executed a number of local men after the organisation said they admitted to being agent provocateurs involved in the bombings while working for British military intelligence.

Stoking Sectarian Violence

British troops and police investigate a couple behind the Europa Hotel in Belfast, 1974. (BeenAroundAWhile, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons)

By the mid-1970s, sectarian violence became more pronounced and vicious, with the rise of hyper-sadistic killings by a loyalist death squad known as the Shankill Butchers in Belfast, as well as by others, assassinating Irish Catholics after torture in “romper rooms.”

Fear stalked the streets of Belfast and the sectarian cauldron was being stoked by British military intelligence. A policy of reducing Britain’s regular armed forces and pushing the province’s Protestant police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), and the local militia, the Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) to the frontlines, further sectarianised the conflict.

The IRA had its share of successes against British military intelligence during the early period of the conflict, but much less so as the conflict continued.

Brendan Hughes, now deceased, played a key role in striking back at Kitson, even managing to tap phones at the army’s headquarters at Lisburn. After interrogating two captured Military Reaction Force operatives, Seamus Wright and Kevin McKee, he gained information that would later result in attacks on MRF fake businesses, killing several undercover soldiers. A massage parlour in north Belfast, an office in the city centre and a laundry van were hit simultaneously on Oct. 2, 1972.

The MRF’s Four Square laundry operation used a van to collect intelligence when touting for custom around Belfast. Clothes were collected from homes and forensic tests run for traces of explosives, blood and firearms before the items were washed, dried and returned to residents.

“The Dark told us the captured agent provocateurs said they’d been trained at Palace Barracks in Holywood [M15 headquarters in Northern Ireland]. They gave the Four Square operation away, before being executed,” McKearney said.

The IRA ambushed the van as it entered the Twinbrook housing estate in west Belfast, machine-gunning it, killing Tedford Stuart, although the IRA said two other soldiers were killed.

The MRF was disbanded in 1973 and replaced by the 14 Field Security and Intelligence Company, followed by the establishment of the notorious Force Research Unit (FRU) in the 1980s, which handled agents like IRA internal security boss Freddie Scappaticci.

Winters sued the Ministry of Defence on behalf of the family of the soldier killed in the Four Square botched operation. Minutes before talking with Consortium News he’d received word the MoD’s lawyers had signalled they wanted to settle the Telford Stuart case before it reached court.

“The family sued the MoD on the basis that the activities and failings exposed their relatives to risk of assassination and attack,” Winters says.

Kevin Winters. (Courtesy KRW Law)

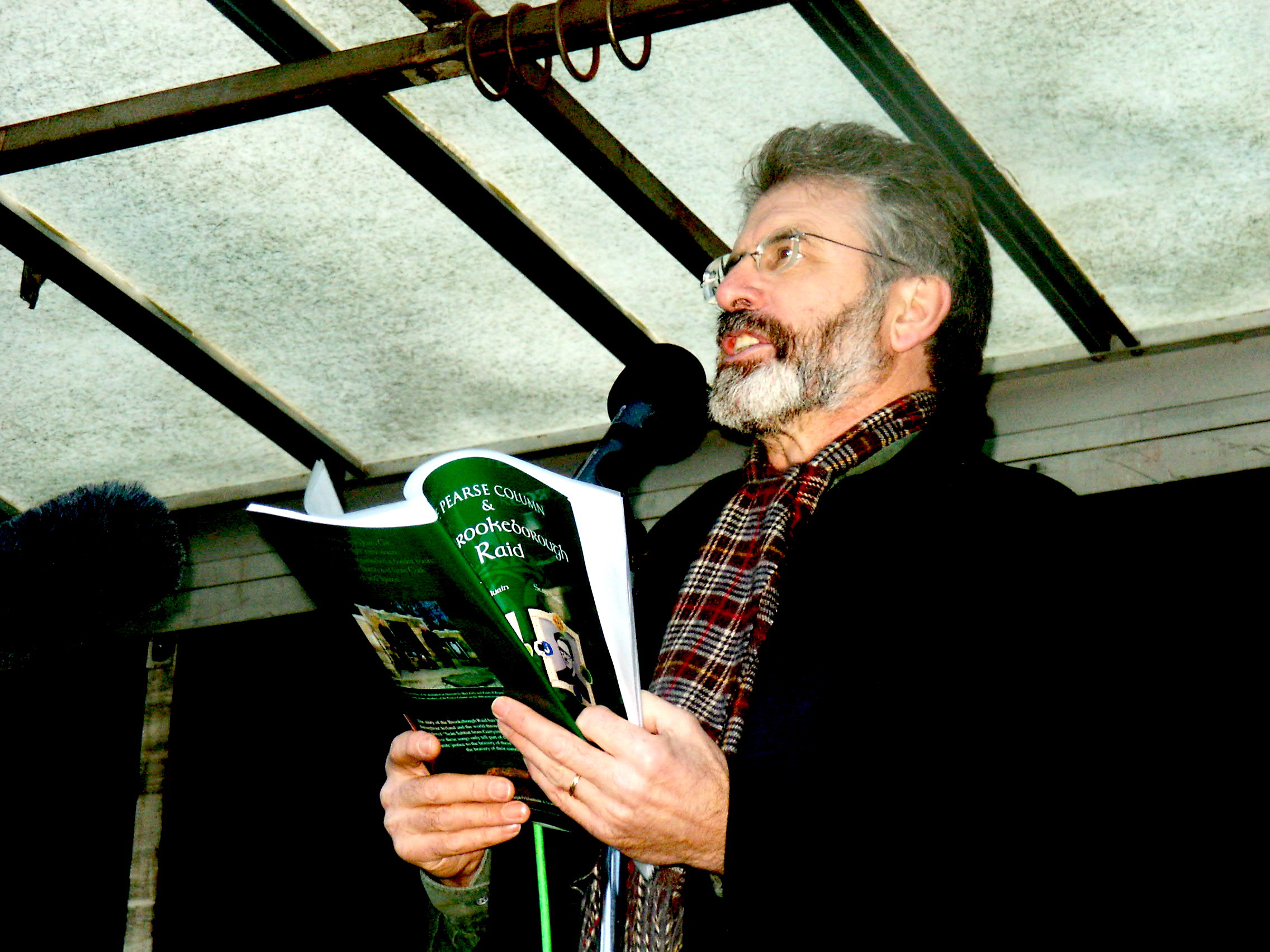

“I had a hunch that if we set this case down for trial, the MoD might want to talk… that we’d make bring them to the table, because the threat of witness subpoena, subpoenaing all and sundry, whoever is still alive, including [former Sinn Fein President and IRA leader] Gerry Adams, to see what people knew about this operation, was just far too toxic and the MoD and the Crown solicitors have seen fit to just try and negotiate this and settle it…

“I think this is an example of the latent threat and power of civil litigation. Four Square laundry was never going to be the subject of a criminal investigation, nor an inquest, because it was far too long ago… It’s out of time, the temporal jurisdiction is set down, the Supreme Court precludes Four Square laundry or other MRF cases from ever seeing the light of day.

“But civil litigation is so much more flexible and here we have this Kitsonian experiment of the MRF generally, and Foursquare laundry in particular, where Kitson’s hand is somewhere on that, and the state take a view and they’ve gone ‘you know what, rather than have a shit fest of civil litigation, where we don’t know what’s going to happen, we’ll take a pragmatic view, and we kill it off, pay out some damages and put it to bed.’ ”

Winters believes the High Court ruling in London in January that Gerry Adams could be sued in a personal capacity but not in a corporate capacity as a member of the IRA potentially strengthens the legitimacy of civil proceedings as a way to hold the state accountable for its use of Kitsonian repression.

“The Kitson experiment, if you like, of suing him in an individual capacity might have actually set the tone a number of years ago for what is now impossibly in place, and what might now become a norm as opposed to an exception,” Winter says.

There are now multiple cases where the MoD is seeking to settle. But the approach in some ways is a victim of its own success, as it means exposure of the inner workings of the state in perpetuating the crimes is limited.

Gerry Adams giving a public reading at a World War I & II memorial event in 2001. (Miss Fitz, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

“The spectre of ex-British army soldiers still alive, fit to come to court, looms large I think in the decisions of the MoD to shut all this down,” Winters says. He went on:

“The Kitsonian mantra put in place throughout all the sectors of the conflict is now going to find itself the subject of a vast number of settlements and resolutions, but without ever having a judicial input and analysis into these Kitsonian experiments.

So, there’s an element of disappointment, personally, that a court is never really going to get to grips with that. But on the other hand, anything involving Kitson — and if you look on the basis that his hand is everywhere — you’re going to have all these cases settling and a series of state settlements, these statistics say an awful lot as well.

To the man or woman in the street, whenever you settle in relation to a conflict-related case all those years ago, and the state pays out, even though there may not be fulsome apology, and even though there may be no admission of liability, collectively, case after case after case resolving and families getting damages at the door of a court, I think there’s some traction in that as well. I think that there’s some positive methods that can be delivered out of that.”

Threat of Kitson’s Experiments in West

Ciaran MacAirt’s grandparents lost their lives in one of the more heinous crimes of the conflict — the bomb attack on McGurk’s Bar in north Belfast in 1971, which was linked to military intelligence. It killed 15 people, which police blamed on the IRA. There is archival evidence Kitson acknowledged the cover-up.

A disturbing question remains, now, after Kitson’s death, concerning his legacy. Could Kitsonian experiments in Northern Ireland be a harbinger of what may come elsewhere, a wider barbarism prosecuted by state forces within other Western liberal democracies against their own citizens?

“Kitson foresaw the time that his techniques may have to be used in Britain itself,” MacAirt points out. In a conversation with MacAirt in 2008, Colin Wallace, a former army intelligence figure in Northern Ireland and a psychological warfare specialist, explained the context of Kitson’s belief in the early 1970s that the army may need to deploy its dirty war tactics in Britain itself at some point.

“Wallace described the period thus to me: ‘This was a time of the Red Threat. Unions were getting stronger… strikes and the three-day working week. We expected tanks to roll down Mayfair at any time. Northern Ireland, for us, was a social experiment.’ ”

Decades later in 2015, then Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn presented a similar type of threat to elements of Britain’s military-political leadership. In widely reported comments made to The Sunday Times, an unnamed senior military general, who had served in Northern Ireland, warned of mutiny if the leftist gained power.

He was reported as saying members of the armed forces would challenge Corbyn if he was elected into government and attempted to end Britain’s nuclear Trident programme, leave NATO or reduce the size of the armed forces.

In light of such statements, a worry that Britain’s counter-insurgency chickens will come home to roost remains reasonable, as the West faces a period of increasing internal political tensions and social discontent.

Mick Hall is an independent journalist based in New Zealand. He is a former digital journalist at Radio New Zealand (RNZ) and former Australian Associated Press (AAP) staffer, having also written investigative stories for various newspapers, including the New Zealand Herald.

Views expressed in this article may or may not reflect those of Consortium News.

Thank you for this article, along with the previous one. They vividly illustrate the extent to which we were propagandised about that conflict, at the time those events were occurring.

At that stage, I was a young adult. I’m of Irish descent, grew up as a Catholic. We were certainly told by the news media in NZ that it was a sectarian conflict. In recent years, especially since the mosque murders in Christchurch, commenters here have said the same thing. I have pointed out that it wasn’t. And isn’t. Such people need to read your articles; unfortunately, they probably won’t.

Thank you Sir. Shinning a light into the colonial dark.

Democracy means nothing to these people. The armed forces may have challenged Corbyn “if he was elected into government” (Should read: If the British people, in majority, exercising their democratic rights in a peaceful election chose their representatives in the House of Commons) and should Her Majesty’s Government act to end Britain’s nuclear Trident programme, leave NATO or reduce the size of the armed forces? This style of treason could be countenanced? Those involved should be eating porridge. When the citizens speak their voice is law. The armed forces shall obey.

Radio New Zealands loss CNs gain

“Radio New Zealands loss CNs gain”

Agreed. Were it the case that RNZ retained journalists of Mick Hall’s calibre, and broadcast their output, I’d still be listening to it.

Thank You Mr Hall

Proud to see a New Zealand independent investigative journalist. Possibly the only one. Right now, as we await the outcome of Julian Assange’s final court case I recall the years and years we tried to get some media coverage about Julian Assange in New Zealand. There was none.

Heyyyy. Nicky Hager (staunch friend of Julian Assange) is still very much alive and active! John Campbell and Gordon Campbell are also excellent.

Thanks for your kind words Lynne. As Andrew says there are some notable independent Kiwi journalists out there, including Nicky Hager, the only New Zealand journalist who came to my aid when the RNZ debacle was instigated. Another great journalist is Glen Johnson and it’s an indictment of NZ legacy media that his foreign copy hasn’t featured on their platforms over recent years.

Great article, Mick.

Keep pushing

“A disturbing question remains, now. Could Kitsonian experiments in Northern Ireland be a harbinger of what may come elsewhere, a wider barbarism prosecuted by state forces within other Western liberal democracies against their own citizens?”

Absolutely, and both Israel and the US has form in this regard. Tonkin Gulf springs to mind, and frankly, Oct 7 has rather suited Israel’s fascist purpose has it not?

Thank you for this article with its profound insights into the Irish ‘troubles’. Always blame the scapegoat – the one who won’t conform – when you are a narcissist like Britain.