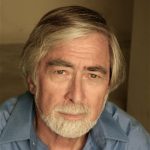

Citing examples of Richard Nixon’s leadership, historian Joan Hoff-Wilson refers to Henry Kissinger as “a glorified messenger boy,” writes Robert Scheer.

President Nixon and National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger chat with staff member aboard Air Force One, enroute to China, Feb. 20, 1972. (Richard Nixon Library/Wikimedia Commons)

By Robert Scheer

Scheer Post/Los Angeles Times

With the death of Henry Kissinger, there is a lively national discussion of the crimes and accomplishments of the Nixon administration that Kissinger helped lead.

With the death of Henry Kissinger, there is a lively national discussion of the crimes and accomplishments of the Nixon administration that Kissinger helped lead.

Although Kissinger won the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize for negotiating a cease-fire in Vietnam and has generally received credit for opening diplomatic relations with communist China, Robert Scheer argued in this LA Times article on March 8, 1984 that Nixon deserves the credit for the groundbreaking foreign policy decisions made throughout his administration.

Nixon responded in a letter to Scheer:

“A number of people have written to me about your article in the Los Angeles Times but I had not had the opportunity of reading it until I received it from you. I want you to know that I appreciated your very objective and comprehensive coverage of some of my activities since I left office.”

Nixon invited him to a subsequent interview in New York, also written about for the LA Times.

Deeds Re-Examined — Nixon: Scorn Yielding to New Respect

Los Angeles Times

March 8. 1984

By Robert Scheer

Richard Nixon is coming on strong. After a decade of ignominious forced retirement following the disgrace of the Watergate scandal, the old warrior is now back, writing books and articles, advising the President’s advisers, meeting foreign heads of state, and granting carefully selected television and print interviews.

And what he has to say may confound the expectations of his many detractors. For in this incarnation, Richard Nixon reminds not of the vindictiveness of enemies lists, the obstruction of justice, or the break-in of a psychiatrist’s office perpetrated by “plumbers” on his staff, but rather of the grander shifts of foreign policy in what he views as the pursuit of global peace.

The new Nixon is Nixon as he would prefer to be remembered. His latest book, The Real Peace, is a defense of his policy of détente with the Soviet Union and summit meetings between the superpower leaders.

What is more surprising, the Nixon Administration, scorned for so long, is also coming in for more favorable treatment by some commentators.

A small but growing number of historians, scholars, and even rival politicians are beginning to re-examine the Nixon era and to challenge the view commonly held of Nixon as a failed President, the most disgraced chief executive in American history.

Nixon in his reemergence remains totally unrepentant about his Administration, which he insists was a glorious one despite some excesses here and there. And even some victims of those excesses, such as former Senator George S. McGovern, his 1972 opponent for the presidency, acknowledge that the Nixon era looks better with the passage of time.

“In dealing with the two major Communist powers, Nixon probably had a better record than any President since World War Two,” McGovern noted in a recent interview with the Los Angeles Times. “He put us on the course to practical working relationships with both the Russians and Chinese,” an achievement which “stands in sharp contrast to the rigid, unyielding, backward-looking approach that Reagan takes toward all Communist regimes.”

Reagan’s foreign policy appears to be the major cause of the current reappraisal of Nixon. “Nixon is beginning to look better and more interesting after three years of Reagan,” noted Jonathan M. Wiener, a historian at UC Irvine, “even among younger historians who were influenced by the anti-Vietnam War movement.”

“History is all relative, and if you compare him to the current occupant of the White House, especially in his handling of foreign affairs, it’s no wonder to me there’s a nostalgia for Nixon at the helm,” observed Robert Sam Anson, author of a forthcoming book about Nixon.

Swept Away By Watergate

Anson said his book “is not an apologia for the bad things he did,” but he added that Nixon “did a number of undeniably good things that have been forgotten. He negotiated the first and only strategic arms limitation treaty, the opening to China. He ended the war, ended the draft; the eighteen-year-old vote came under his presidency. He did a lot of good things and they all got swept away by Watergate.”

Author Harrison E. Salisbury, who has been critical of Nixon in the past, after reading an advance copy of The Real Peace, wrote to the former President and hailed his “vision” as “superb.” Salisbury added, “As a primer for the country, and President Reagan, I cannot imagine a better [one].”

But other scholars and politicians still contend that however sound some aspects of Nixon’s foreign policy were, they are not enough to brighten his tarnished image.

“To say that Nixon had the sensible and obvious view, shared by my thirteen-year-old daughter though unfortunately not by the incumbent President, that we must deal with the Soviets, is not sufficient to absolve him of the abuses of power represented by Watergate,” John D. Anderson, the former Republican congressional leader and Independent presidential candidate, said in an interview.

That more critical view continues to dominate both journalistic and academic circles, where the memory of Watergate defines the man. In what remains one of the oddest chapters in American history, this President who had left his mark, as few have, on American foreign policy and who continues to be prolific in his pronouncements, has become, in some quarters, very much a non-person — more the perpetrator of a scandal to be forgotten than the architect of a policy to be studied.

Although without much honor in his own country, Nixon continues to be admired abroad. Georgy A. Arbatov, a member of the Soviet Communist Party’s Central Committee and an expert on the United States, said in an interview last year that the Soviets consider Nixon to be the most effective post-war President.

Many Western Europeans share that view. “The Europeans always had a much higher opinion of Nixon than did the Americans, and looked upon Watergate more as a bagatelle than a crime,” observed foreign policy expert Ronald Steel. “It’s a difference of historical background. The Europeans are used to this sort of thing.”

Since he left office, Nixon also has made several visits to China, each time receiving accolades for having opened the door to U.S.-China relations in 1972. The Chinese, who have never shown any interest in Watergate, explain their admiration for the former President by quoting an old Chinese proverb, “When drinking the water, don’t forget those who dug the well.”

“Citing [Nixon’s advocacy for opening relations with China] and other examples of Nixon’s leadership, historian Hoff-Wilson refers to Kissinger as ‘a glorified messenger boy.’”

Nixon’s standing is also high in the Middle East. When Egyptian President Anwar Sadat was assassinated in October 1981, Nixon—along with former Presidents Jimmy Carter and Gerald R. Ford—represented the United States at his funeral. He then made an eight-day trip to Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia and, on his return, he issued a statement urging direct negotiations between the United States and the Palestine Liberation Organization.

In Israel, however, Nixon is still fondly remembered as the first U.S. President to visit Jerusalem—a trip he made on the eve of his resignation. “Nixon was then a hated person on the verge of impeachment in Washington,” Amir Shaviv, a leading Israeli journalist, recently recalled. “But when he came to visit Jerusalem, thousands cheered him on the streets and the government of Yitzhak Rabin received him as a great friend.”

Yet in this country, despite the vast outpouring of books and articles devoted to his involvement in the burglary of the Democratic Party headquarters and related sordid events, there has been scant notice paid to the major shifts in policy brought about during the Nixon years.

“We haven’t had an historical interpretation of him since Watergate, but we’ve had a number of hysterical ones,” charged historian Joan Hoff-Wilson, a University of Indiana professor whose study of the Nixon years will be published this summer. “It’s the worst body of literature I have read on anyone, presidential or otherwise. It’s so skewed by Watergate that you can’t get a picture of him.”

Hoff-Wilson, executive secretary of the Organization of American Historians, has interviewed the former President and attributes much of this bias against him to the fact that “journalists have a vested interest in making sure that nothing good is ever said about him… Watergate is their major claim to fame and the whole investigatory syndrome that followed.” By contrast, Hoff-Wilson argues that the Nixon Administration was the “most significant since [Franklin D.] Roosevelt’s.”

Whether or not one accepts that judgment, the abiding mystery of Richard Nixon is how a politician described by many as totally lacking in moral integrity and devoid of an intellectual and programmatic commitment could have achieved so much clarity of purpose in his presidency.

A Complex Assessment

How is it that this man, who has been described in much of the Watergate literature as little more than a charlatan of the first order, accomplished so much as President? How can it be that Nixon, who for most of his life was derided by his liberal critics as a primitive and demagogic anti-Communist, who began political life in California by smearing his congressional opponent as a Red, now campaigns for “hard-headed détente” with the Soviets?

Some historians feel that such questions will inevitably compel a more complex assessment of the Nixon presidency, There are already some signs in the academic community of a perception that Watergate may be too narrow a window for viewing the Nixon legacy.

“Historians are trying out a Nixon revisionism in the classrooms,” Stanford University historian Barton J. Bernstein said in a recent interview, “but so far a revised view of Nixon has not made its way into the literature.”

Hoff Wilson: “… the prolonged negotiations over Vietnam were really part of Kissinger’s egomaniacal tendency to prolong negotiations. The shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East fell apart.”

Bernstein, who specializes in modern diplomatic history, is convinced, however, that “in another ten to fifteen years, I will be assigning literature that will argue the case for a reassessment of Nixon and for upgrading him because of some of his accomplishments in foreign policy.”

Historian Hoff-Wilson is considerably less optimistic about the possibilities for a revisionist view of Nixon. “Until we die, I don’t think there will be any significant change in the intellectual and published elite literature on Nixon,” she said.

Hoff-Wilson, forty-four, considers herself part of that generation which opposed the war in Vietnam, but she chides her peers for not being able to transcend the “trauma” of that experience. “Most of my colleagues who are against him came out of the antiwar movement,” she said.

One of her colleagues, Tufts University historian Martin Sherwin, has argued that his generation of historians is correct in making Nixon’s role in Vietnam central to an evaluation of his Administration.

“Nixon is responsible for reaching a settlement of the Vietnam War in 1973 that he could have had in 1968, and this generation of historians remembers that and should,” Sherwin said. He resists a revisionist view of Nixon “because there is no new body of documents or other information to warrant such a revisionism.”

“I come down on the critical side,” Sherwin said. “I think it’s a mistake to believe that because the Reagan Administration has been such a disaster in the area of foreign policy, that that validates some of the worst policies that the Nixon Administration had pursued. After all, the U.S. bombing of Cambodia was an illegal, criminal act—a war against that country that was not approved by Congress.”

UCLA historian Robert Dallek also disagrees with historians such as Hoff-Wilson who favor a major Nixon revision-ism. “The history textbooks already give Nixon his due on détente and the opening to China and also hit him pretty hard on Vietnam and Watergate,” Dallek said. “I don’t think Hoff-Wilson’s view of historians being blindly prejudiced toward Nixon is correct. The bulk of historians have made a more balanced assessment.”

Hoff-Wilson conceded that “the negative things remain — Vietnam and the way that was handled, the secret war in Cambodia, and Watergate. I don’t want to whitewash those things, but the problem is that that is all that’s ever talked about. The problem is the imbalance with which we see him.”

Hoff-Wilson has found that attempting to provide that balance is no easy chore: “I tell you, I have had the worst time in social gatherings, people just attack me. I don’t think we will get beyond that in our time—we will constantly run into that.”

Some tend to mistrust Nixon because of what historian Bernstein called “mud-slinging” in his first political races in California, and they “came to have that view confirmed by Watergate.”

“One has difficulty liking Nixon,” Bernstein said. “There is nothing winning about him; he’s suspicious, he’s covert, he’s evasive, defensive, and lacks a sense of humor. There is an unwillingness on the part of historians and journalists to distinguish between the man and his policies, though obviously Watergate wedded the two.”

But Bernstein added,

“I think it is possible to dislike Nixon and to revile him for his brutal selective use of power as in the carpet bombing of Vietnam or the overthrow of the democratically elected, Marxist government of Salvador Allende in Chile, yet one should recognize that no American leader in the last forty years has been more calculatingly cautious about the use of American power in a setting of potential global conflict.”

Nixon with Kissinger, Gerard Smith of the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, and Secretary of State William Rogers, 3/15/1969 (Nixon White House/Wikimedia Commons)

But for many, Nixon’s Third World policies remain a sticking point.

“With the exception of the Soviet Union and the China card, which are admittedly very big issues, revisionists are going to have a hard row to hoe,” said UC San Diego historian Michael Parrish. “We cannot ignore situations like Cambodia, Chile, and the way in which the war in Vietnam was prolonged much beyond what was a reasonable opportunity to end it. Those are pretty large black marks against him.”

A similarly acerbic view was offered by Duke University political scientist James David Barber, who specializes in the presidency.

Any more favorable reassessment of Nixon is “puzzling,” Barber said, because “he is the first President in all of history to have been tossed out. He is a demonstrated fabricator of history. His policies in Vietnam are responsible for a great many more persons being killed than needed to be. He would likely have been the first guy to have been convicted of a crime as a President if Ford had not pardoned him.”

The public at large has proved as unforgiving of Nixon over Watergate as the journalists and historians. According to a Washington Post-ABC poll in June 1982, seventy-five percent of Americans said they thought Nixon was guilty of wrongdoing in the Watergate affair. By a margin of more than two-to-one, they felt he should be granted no future role in national affairs.

“Nixon took issue with those who are pushing for a reassertion of U.S. superiority and urged Reagan to accept the Soviets as equals”

Since he resigned the presidency in August 1974, in the face of possible impeachment by the House of Representatives, Nixon has been given to long periods of seclusion, hiding behind the protection of the Secret Service to avoid encounters with the public or press.

But with increasing frequency he has, in the manner of a respected ex-President, ventured forth with speeches, interviews, articles, and books, and meetings with foreign and domestic dignitaries.

Nixon, who lives on a $1 million estate in New Jersey, commutes fifty minutes daily to the office quarters granted him as an ex President in the New York Federal Building, where he maintains an arduous schedule of meetings. Over the last several months, for example, he met with representatives of Nepal and Japan, with the widow of Sadat, and with the Crown Prince of Jordan. King Hassan II of Morocco dined with Nixon at his New Jersey home.

Nixon has continued to travel widely over the last two years, visiting seventeen countries, where he has been welcomed for discussions with no fewer than sixteen heads of state. His five books have all sold well and indeed are often bestsellers abroad.

In The Real Peace, his latest book, Nixon has extended his campaign for what he calls “hard-headed détente,” although that concept is not much in vogue in the United States any longer. Whereas Nixon favors a military buildup, he stresses the limits to the military option.

So obsessive is the former President about the urgency of the message of The Real Peace that he paid for its initial publication and sent 1,200 free copies to friends and business associates. One of those who received a copy was Samuel Summerlin, president of the New York Times Syndication Sales Corp., who bought the rights to the book and successfully marketed it to magazines and book publishers throughout the world. Little, Brown & Co. recently published an edition in this country.

The book’s message is bold and simple: “The two superpowers cannot afford to go to war against each other at any time or under any circumstances. Each side’s vast military power makes war obsolete as an instrument of national policy. In the age of nuclear warfare, to continue our political differences by means of war would be to discontinue civilization as we know it.”

Nixon was not available to the Los Angeles Times to further delineate his views, saying through a spokesman that he wanted “his book to speak for itself.”

While Nixon studiously avoids public criticism of Reagan, The Real Peace reiterates his earlier defense of détente in terms that challenge key tenets of the Reagan foreign policy.

And in an interview last month with the West German magazine Stern, which bought the serialization rights to his new book, Nixon took issue with those who are pushing for a reassertion of U.S. superiority and urged Reagan to accept the Soviets as equals.

He said, “I always accepted the Soviet Union, when I was President, as a superpower… It is very important for President Reagan to do exactly that, to recognize that they are … equal as a superpower, but it is very important also to recognize that they are different … The differences will never be resolved. We just have to live with it.”

Nixon continues to deny that there is any contradiction between accommodation with the Communist giants and fighting communism in Vietnam or elsewhere. On the contrary, his “hard-headed détente” envisions the United States mounting militant opposition against any sign of Soviet expansionism.

Nixon’s view of the Soviets is not simple. He frequently points with pride to his “hawkish” views and insists that he is not “soft” on the Soviets.

The complexity of his view was demonstrated this past May when he took issue with the pastoral letter adopted by the Roman Catholic bishops that questioned the morality of nuclear deterrence. In a letter to the New York Times, Nixon defended a policy of deterrence that includes “deliberate attacks on civilians,” if necessary, as a counter to attacks by Soviet conventional forces.

And, as he is frequently wont to do, he blasted “well-intentioned idealists who cannot face up to the fact that we live in a real world in which the bomb is not going to go away.”

But instead of completing that sentence in a Strangelovian way by extolling the possibilities of nuclear war, Nixon added, “We must redouble our efforts to reduce our differences with the Soviet Union, if possible. Where that is not possible, we must find ways to live with them rather than to die over them.”

Those who have been close to Nixon tend to stress the complexity of the man and his thoughts.

“Don’t generalize with this guy,” warned former Nixon aide John D. Ehrlichman in an interview. “You will run a risk of being dead wrong if you do, because he’s a very complicated mass of cells.”

Historian Bernstein traces Nixon’s notion of limits to American power to the Dwight D. Eisenhower era and argues that it provided Nixon with an overall strategy permitting selective “and often brutal” intervention in world affairs within a context of keeping the global peace with the Soviets.

This sense of limits still forms the core of Nixon’s thinking. “We recognized that our two countries were locked in competition, and each of us was determined to protect his own country’s interests,” Nixon wrote in the New York Times last year, in an article discussing his three summit meetings with the late Soviet Premier Leonid I. Brezhnev. “But we also recognized that our countries shared certain common interests, which made it mutually advantageous for us to compromise or otherwise resolve an increasing range of our competing interests.”

Before He Ever Met Kissinger

Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir, Nixon and Kissinger, the White House, October 1973. (Central Intelligence Agency/Wikimedia Commons)

The antecedents of the Nixon foreign policy add credence to the claim by many Nixon associates that it was the President himself—not Henry A. Kissinger—who crafted the broad outlines of foreign policy in his Administration. They note, as an example, that he first advocated the opening to China in a Foreign Affairs magazine article in 1967, before he had ever met Kissinger.

Citing that and other examples of Nixon’s leadership, historian Hoff-Wilson refers to Kissinger as “a glorified messenger boy.”

“He has grabbed all of the credit that he possibly could, and without merit,” Hoff-Wilson said. “I believe on my reading of the record that the prolonged negotiations over Vietnam were really part of Kissinger’s egomaniacal tendency to prolong negotiations. The shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East fell apart.”

The attempt to apportion credit or blame between Nixon and Kissinger will likely be the major point of contention in future assessments of that Administration, according to historian Dallek.

But Dallek said it will not be possible to definitively answer that question or to revise current estimates of Nixon until the release of more documents from the Nixon White House.

Forty-two million documents from the Nixon era are currently in the custody of the General Services Administration, but the vast majority have not been made public. Last month, a federal judge in Washington acceded to the request of former Nixon aides and temporarily blocked the release of 1.5 million documents; the aides had complained that the documents were private communications and ought to be shielded under the Privacy Act.

At this point, only Nixon and those persons he designates have access to those files. Ehrlichman is one who was granted access by Nixon.

Erlichman said that Nixon’s image as the prime architect of his Administration’s foreign policy will be enhanced at Kissinger’s expense once the remaining White House tapes and other documents are released.

To illustrate his point, Ehrlichman supplied the Los Angeles Times with 1,000 pages that had been released to him from the U.S. Archives, which contain notes of daily White House meetings of the President and his top staff. In those entries, it is clearly a matter of Nixon calling the shots on foreign policy, down to detailed instructions to Kissinger even when the latter was off on one of his stints at shuttle diplomacy.

Nixon “advocated the opening to China in a Foreign Affairs magazine article in 1967, before he had ever met Kissinger.”

Those papers, as was the case with earlier releases of Nixon tapes and documents, suggest two extremely different views of the man. On the one hand, there is Nixon the consummate statesman, knowledgeable about the world, well prepared for his meetings with other heads of state, and capable of a cool, dispassionate approach to bargaining.

But the notes also reveal another, less stable Nixon, on one occasion apparently so drunk that Air Force One had to circle Andrews Air Force base until the President sobered up enough to approve a controversial press release.

Future historians will have to sort out the two Nixons in any reappraisals of the man and his Administration. And clearly there were two Nixons.

As Nixon’s former speechwriter, Raymond K. Price Jr., put it, “Between the anguished, cornered Richard Nixon of the Watergate transcripts and the confident, self-assured Richard Nixon speaking the language of power, the contrast is as stark as it was between his return in triumph from Peking and his departure in disgrace to San Clemente. Both are part of the man. Both are part of the record.”

Robert Scheer, publisher of ScheerPost and award-winning journalist and author of a dozen books, has a reputation for strong social and political writing over his nearly 60 years as a journalist. His award-winning journalism has appeared in publications nationwide — he was Vietnam correspondent and editor of Ramparts magazine, national correspondent and columnist for The Los Angeles Times—and his in-depth interviews with Jimmy Carter, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, Mikhail Gorbachev and others made headlines. He co-hosted KCRW’s political program Left, Right and Center and now hosts Scheer Intelligence, a KCRW podcast with people who discuss the day’s most important issues.

Understand Nixon’s background …. where he came from.

Nixon rode the Hate of McCarthyism to power. Nixon was an ally of Joe McCarthy, and largely became Veep because the more sensible Eisenhower needed to try to ‘unify’ the party with the wing that was heading off into full blown paranoia and hate. Veep Nixon and Sen McCarthy were allies in the hunt for ‘commies in the State Dept.’ Hate was always a Nixon trump card.

Nixon tried to ride this to the White House, but ran into the Kennedy’s Camelot machine, and what Daniel Ellsberg later exposed as the Big Lie of the “Missile Gap.” ( see “The Doomsday Machine”) Seymour Hersh’s book on Camelot is worth a read as well. But, regardless of how it happened, Nixon lost, and the last popular American President began his short time in office.

Later of course, the Democrat War Machine and its thirst for wars and power around the world led to the winning election of Nixon in 1968. Where we saw the war continue on and on, with the biggest losses of American lives and in overall slaughter continuing 1968-74. This included the lovely notion of a Christian Nation engaging in a Christmas Bombing Campaign to celebrate the birth of the Prince of Peace by doing to North Vietnamese cities what is currently being done to Gaza. This was the era of the Phoenix program of assassination and torture to try to ‘pacify’ Vietnam.

And at home, we got CREEP. The committee to re-elect the President. We got the Plumbers, to track down and seal those pesky ‘leaks’. We got breakins. Watergate was when they screwed up and got caught. We got election interference, as the CREEP tried to keep Democrats they viewed as dangerous out of the nomination by a series of dirty tricks and crooked media coverage of the results. We got Kent State, and US Troops firing on pro-democracy, peace protestors. We got the 1972 election where the ‘corporate Democrats’ like Humphrey and Daley were happy to see CREEP win as long as the hated McGovern and the Peace Movement was kept from power. We got the long campaign of lies trying to cover up all the crimes and the lies. Nixon of course fully supported the lies of the Warren Commission, like all post 1963 American politicians.

Scheer should have been conducting these interviews in a prison visiting room.

By letting Nixon escape prison, America thus empowered the Nixon sycophants like Chief of Staff Dick Cheney to go forward without fear while putting such anti-American, Nixonian notions like ‘the Imperial Presidency’ into effect. Roger Stone is another name from the Nixon era that has done great damage to our current country because America failed to properly punish the crimes of Nixon. What would America look like today, if Nixon, Stone and Cheney had died in prison while paying for their crimes?

“Tricky Dickie” is the description that stuck with me then, and now. I hesitate to use an ad hominem because it is too easy. However, like the late Senator McCarthy from Wisconsin, Nixon accused whoever he was running against or didn’t like of being Communist. Since all politicians proceed by scaring us and then, offering the solution – themselves, of course – this polarization isn’t helpful. The assertion the Nixon was two people is an acceptance he was a liar. I’m not saying I’m not, but I try to avoid it.

While this excellent 1980s article makes clear that Nixon’s objectivized legacy would remain moot long into the future, it is totally damning of Kissinger’s over puffed-up foreign policy credentials even decades before he alas kicked his diplomatic bucket. Sure Nancy Kissinger wouldn’t approve of it !

No surprise a scapegoat for our lying bipartisan misadventure to save the freedom of the 10% leftover religious adherents of a world wide empire the Roman empire morphed into.

Without the republican he wouldn’t have been impeached and they could profit in the next election potentially and as a bonus Kissinger’s friend Nelson Rockefeller who had problems getting nominated magically become VP by appointment too. Putting the breaks on the emerging youth culture so that soon Reagan and GHWB and Bill Casey could rebuild the military industrial for bigger things. Things like pivoting to the Middle-East where threats of oil embargoes to the fuel of B-52’s.

Things that may be related to a lone assassin of a Saudi King by lone assassin and the downfall of the Shah of Iran and a sting to new hopes we had for the Iranian cleric like our previous hopes for Castro that went sour and brought a religious reaction from the new keeper of the Spanish faith.

s Secular society seems to be losing to faith based controllers with the longest history of empire manipulation ever known to mankind. This century may be a pivotal time for human civilization to pivot away from full spectrum dominance behavior for false profits.

The left leaning historians like Nixons foreign policy more now that they understand the leftward shift that he made.

The 1984 article is interesting in cheering Nixon for treating the Soviets as equals and being nice to them. Where are the Soviets now? I think the demonized Regan was part of that dissolution.

Yes, the draft ended under Nixon too late for me to benefit).

But he also signed bills giving 18 year old the vote. A mistake. Probably should have raised it to 25 when the brain is actually matured . Other mistake include abandoning the gold standard ( paving the way for more inflation) and initiating gas rationing which resulted in gas shortages and long lines at the pump.

As a former Republican I’m not very forgiving of most of the Nixon presidency.

Getting off of the gold standard was inevitable. With an ever-expanding economy and hence ever-expanding money-supply, there’s only so much gold to back it up. Not that debt-based fiat currency is any better, it isn’t, but the problems with our monetary-system go way beyond whether or not it’s a good idea to back the currency with gold. It isn’t. The root of that problem, as ever, is who controls the creation and regulation of the currency. It’s supposed to be the Congress/Treasury, according to the constitution, but the private banking interests have gotten their tentacles into it and that is the crux of the problem. Most Congresspeople today don’t even understand how the monetary-system works, and think the Federal Reserve is government-owned. It isn’t.

Fractional Banking

Starting with Truman to the current president, every one of them did not do what was necessary to bring home the POWs left behind after the war ended. Nixon especially had a golden chance but did not. 591 POWs came home as a good will gesture. The remaining 2,500 were left behind the democrat congress did not want a republican president to receive accolades. There was enough praise for everyone.

Watergate was bumbling set up to shaft Nixon. His mistake was trying to protect those who planned and executed the snoop.

He worried more about Watergate, getting reelected than he did about bring our POWs home.

Kissinger’s ego was fed by pandering to Nixon. Kissinger did nothing to bring our men home. Nothing in it for him. He needed Nixon. Nixon did not need Kissinger.

Nixon, for all his paranoia, had good instincts about diplomacy. Was he a good president? He was good at policy. He knew how to make contact and present what was good for the US.